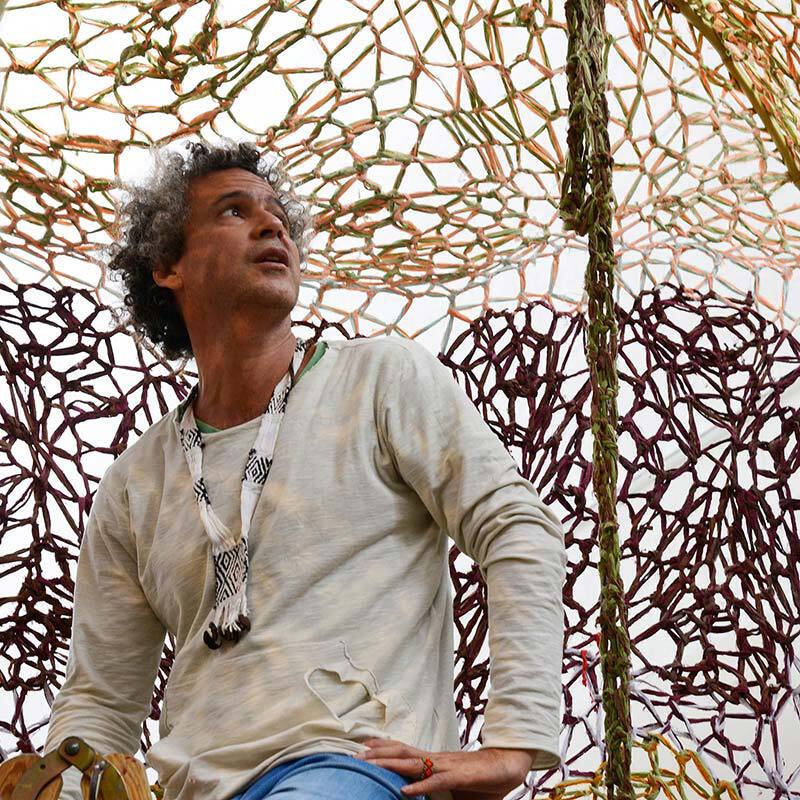

For more than 20 years, Robert Punkenhofer has been involved in international corporate and art management. His agency Art & Idea considers itself a nexus between art, architecture, design, and economics. He has curated more than 100 exhibitions, among them the annual Vienna Art Week. He has served as Trade Commissioner for the Austrian Foreign Trade Organisation in Mexico City, New York, and Berlin, a role that he currently holds in Barcelona. We spoke with the unusual collector about art, his ability to repeatedly create things from nothing, and about his passion for Vienna’s brilliant k. and k. period

Robert, entering your apartment in Barcelona it is immediately obvious that someone for whom art plays an important role lives here.

It’s true art does play an important role in my life. However, I’ve never seen myself as a typical “collector,” in the same way that I do not regard myself as a curator.

How did it come about, your enthusiasm for art?

That is a “big question.” There were some key moments, which inspired my passion for art. I grew up with art, because my parents were very interested in it. In high school I had inspired art teachers, who were a shining example to me. During an exchange year in Paris, I lived with a family in which there was a son, five years older than I who was already at university. This family was a good point of contact for me otherwise I would have been on my own. Besides my language course, I spent most of my time in galleries, museums, and the “Petit Theatre.”

Inspired by Paris, at the age of seventeen, I took the night train from the Gare de l’Est to my hometown Graz. Prior to this, I had made an appointment with the mayor and had informed him, that I wanted to open a Cultural Center. The City Counselor for Youth and Family received me and after having listened to what I had to say, she offered me a space in the House of Youth. I was completely excited until someone showed me the space – it was in the basement. This did not at all correspond to my vision, and I rejected it. Since then I have engaged intensively with art and with exhibiting art. Initially I studied law, but then also art management at New York University.

When did you have your first art space?

That was in 1995, only three months after I had begun to work as deputy Trade Commissioner for the Austrian Federal Economic Chamber in Mexico City. The first exhibition I curated was an exhibition with Austrian artists in my apartment. I think one can speak of a truly “magical moment” for at that time there didn’t exist a professional art space in Mexico City that focused on international conceptual contemporary art. At the time, no museum offered such a space, rather they showed art that I would call “post-Frida Kahlo,” and that is one of the reasons why the art space Art & Idea was so successful. We noticed a demand and filled this void. With the first solo exhibitions of artists like Abraham Cruzvillegas, Santiago Sierra, and Teresa Margolles we received an unbelievable response. Years later, this generation of artists became quite well known. At the Venice Biennale 2003, which Gabriel Orozco had co-curated, were also some Mexican artists represented which I had shown at the time in my rather make-shift Art Space.

You’ve said that you are not a typical art collector. And yet, we see many wonderful works on your walls, including works from well-known artists. How did this art collection happen?

At some point artists suggested that I should ask each artist to donate one work to my not-for-profit work in the Art Space. I thought it was a good idea and began when I was Trade Commissioner in New York. There I also presented exhibitions in my living room. Harald Szeemann, too, visited me there shortly before his last Venice Biennale which he curated in 2001. I did not select specific artworks, but asked the artists to donate one work for the “Art & Idea Collection.” They all enjoyed doing this. Daniel Guzmán for example has given me a wonderful drawing.

A major part of your artworks can therefore be considered documentation?

Yes, one could say so. Only artists with whom I have done projects are represented. These are memories that are close to my heart, like the first preliminary drawings by Vito Acconti, with whom I realized the Mur Island for Graz, the European Culture Capital at the time, in 2003. Or the photographs of the Mur Island by Wolfgang Thaler, whom I greatly appreciate as a photographer to the lamp of Walking Chair or Dejana Kabiljo’s Let them Sit Cake. My son may think that one day this collection will make him rich. I don’t really think so, because for me the sentimental value counts more. My identity is reflected in all I do.

Did you never purchase art?

Of course I did! The first work I bought was by Eugenia Vargas. When it was clear that I would go to Mexico, I researched the art scene and found an article in ARTnews about Eugenia. She is Chilean and lives in Miami. That was the first time I bought an artwork.

Are you searching for new work or artists at art fairs, for example at the Arco Madrid?

Primarily I do! For this year’s Arco, I have done research for the upcoming Vienna Art Week where I am artistic director. For the Vienna Art Week 2016 we will focus on the topic “Seeking Beauty” on the unfathomable nature of beauty, the seductive. Apart from that I only attend the Art Basel, because all the others have become rather interchangeable. When I am looking for artists who interest me personally I am regularly at art festivals and Biennales, and certainly I visit artists’ studios.

Although you have presented exhibitions for years, you say that you don’t see yourself as a curator. Can you explain this?

That’s certainly quite provocative. My respect for “real” curators like Harald Szeeman is still so profound that I simply can’t call myself a curator, even though I have indeed been responsible for many exhibitions. Meanwhile I think there has been an inflation of the term “curator.” The term “curating” has become overblown in the last few years: “Curated Fashion Show,” “Hair Curators,” and “Curated, I don’t know what...”

I simply like to create a thing out of nothing, including among other things exhibitions, projects, and publications. I would not call myself a curator, because I don’t like the word. The original meaning of “curare” – from the Latin – means “to care for something” or “to heal,” things I can identify with. Curare is also the name of a poison. That’s exciting to me. Interestingly, the chamber of commerce refers to me as a curator too. I always had to smile when I was cited as a curator rather than as Trade Commissioner in the context of the exhibition at Milan’s Triennale Design Museum.

As Trade Commissioner you take the Austrian economy abroad and vice versa. How do art and economics go together? How do your colleagues respond to the fact that you are so engaged with art?

It is quite advantageous that I am able to operate well in both worlds. Of course I speak differently with artists than with the participants in an “Austrian Business Circle.” These different languages and also the rapid change between the two worlds is very natural to me. It is precisely the creative input that I get from art that is so important to my work as an Trade Commissioner.

Seen from the outside, some may ask how this goes together. In my eyes, however, one fertilizes the other. In the context of the World Fair in Japan in 2005 for example, I invited Edgar Honetschläger who wanted to realize a Chicken Suit Project with chicken from Nagoya. The Ministry of Economics has called me crazy at the time! Through my experience on both sides it was possible to gain in situ, support of official government institutions. Ultimately, the project became a huge success about which even ABC’s Good Morning America television show reported.

It sounds like a continuous balancing act.

Yes, which in my view is only possible because both my work as an Trade Commissioner and my enthusiasm for art are inspired by passion. I need and love both aspects. This passion I sometimes share with industrialists who are also interested in art and who collect. It may sound surprising, but through conversations about art many contacts can be established in the economic sector.

Art gives you “creative input.” Often great demands are put on art and art is expected to serve as the solution for many problems. Do you believe that art can contribute to the present sociopolitical situation?

That is a very intriguing question. No one can demand political involvement or political art from artists. However, it is a fact that artists have a higher sensibility and they should use it in an intellectual dialog with society. However, artists need their freedom; art has no task and no function! That is how it differs from design. Nevertheless, I do see an opportunity to set themes through art as we have tried with the Creating Common Good exhibition at Kunst Haus Wien last year. However, the largest contribution in a socio-political situation as we have now must be contributed by politics!

It seems as though you did not only collect art but also confront challenges, what will your next challenge be?

Challenges are inevitable. I’ve said that I am not a collector, but there are a few things that I do collect. I always wanted to own old k. a. k. brands, for I love the Vienna around 1900. The entire epoch has a high attraction for me. The former purveyors to the court were the best of the best and all were radical pioneers and innovators in their field.

After some research I have secured the name rights to three old brands. One of them is Ernst Dryden. Dryden was an Austrian, who lived in Berlin and was one of the important graphic designers of his time. The luxury brands of Europe belonged to his customers, for example Bugatti and Chanel. The First World War and a plagiarism scandal abruptly ended his career in Germany. Therefore he returned to Vienna and worked as a designer for the haberdasher Knize am Graben, discerned by Adolf Loos, which still exists today.

In my opinion, Ernst Dryden was the first Creative Director of a men’s fashion label. From styling the fashion icons of his time, at one point he became one himself. He worked with and for big names like Marlene Dietrich and Billy Wilder. Wilder considered him the “most elegant man in the world.” A truly interesting personality!

Another name whose rights I have secured is Christoph Drecoll. He was foremost known for his stage costumes and in the 1880s opened one of the most important salons in Vienna with branches in Paris, New York, and Berlin. He was known as “the Baron, who attracted women.” This brand I have also “collected.” At one point I want to do something with it.

What do you want to do with these brands?

I want to revive them and save them from being forgotten. I am particularly excited about the story of the Prague watchmaker Carl Suchy. He was a master of his trade and his work was known internationally. He was represented with a display of his watches at the World Fair in Paris and even exported to England. His company became one of the most important watch manufacturers in the Danube monarchy. He sent his sons to La Chaux-de-Fonds, where the watch industry and the Art Nouveau heritage were concentrated in Switzerland, and to Vienna. After completing their apprenticeship as watchmakers they entered the parental business, which was renamed Carl Suchy & Söhne. Suchy himself was by the way very socially engaged, which is what I particularly like about him.

These brands are all from another time. Carl Suchy was active almost 200 years ago. Do brands like these still correspond to our Zeitgeist?

Especially in times like ours, in which everything is getting more digitized, I am interested in returning to a trade. I find it fascinating that in the case of Suchy three consecutive generations received the distinction of purveyors, because their “products in regard to elegance and perfection were in accordance with the highest demands.” At the same time, it was also impressive that the last generation of the house of Suchy destroyed the empire because of their addiction to gambling. I believe that the return to an almost forgotten trade and its ideals is a good alternative concept for our time.

With Carl Suchy you enter a completely new terrain. You are not a watchmaker yourself.

That is true. However, the project basically resembles a curatorial process, as I understand it. One researches the archives, in order to find out more about these brands. This is actually research about “Vienna around 1900” and Adolf Loos’s finding “Ornaments are a crime.” Eventually the goal is to realize a product, to end the creative pause of Carl Suchy & Söhne and to develop and build a new watch. That is a process I know – in this case not an exhibition or a festival, but a watch, and also a creative process.

How do you plan to infuse Carl Suchy with new life?

I have gathered around me young talented people who will support me in the process. I have always done it this way. Milos Ristin is designer of the Waltz No. 1, the first new watch by Carl Suchy & Söhne. Reinhard Steger designed the brand world for it. The entire project is directed by the watchmaker Marc Jenni, who has also worked for Tiffany & Co., and is one of the thirty-three members of the Académie Horlogère des Créateurs Indépendants, an association of the best independent watchmakers worldwide. Between us we provide intellectual friction in order to move Suchy forward.

As you’ve already said, it is new terrain for me. I learn an incredible amount that I am able to integrate into my work as Trade Commissioner. For Carl Suchy, I deal extensively with branding and the laws of the luxury industry – expertise that I would not have acquired without Suchy. I have been in much the same situation earlier with art and design topics.

What is your vision for Carl Suchy & Söhne?

The first milestone is to sell the Waltz No. 1 – the name is actually an homage to the Vienna Court Ball (Wiener Hofball) – in a limited edition of 22 pieces. Only then will the watch be manufactured in La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland, where Carl Suchy junior absolved his apprenticeship. Since the watch is completely handmade, its production takes seven months. If you want it as a Christmas present you must place an order for your edition of Waltz No. 1 quickly.

In all my enthusiasm I am aware that I am dealing with a long-term project, for my main profession is Trade Commissioner for Austria in Spain. With the Carl Suchy project it is the ideal rather than the economic success that has priority. This is my principle with many things in life. Meaning is more than money.

Interview: Michael Wuerges

Photos: Florian Langhammer