The scene for contemporary art in Europe’s North is expanding and developing new dynamics as international collectors are watching the scene. With Nordic Notes we regularly cast the eye on the Nordic art and cultural scene, portraying its important actors.

With the initiative to establish a Guggenheim museum, the city of Helsinki has undertaken yet another step to raise its profile among an international art scene that could benefit the entire Nordic region. We met Sanna-Mari Jäntti, who has played a crucial role in the Guggenheim Helsinki project (that unfortunately has been discontinued), to talk with her about the initial challenges of the project, how David beat Goliath in the world’s largest architectural competition, and how doing it the “Finnish way” made all the difference.

Sanna-Mari, as the director of the Guggenheim project in Helsinki at Miltton you probably have one of the most exciting jobs in the Scandinavian art scene these days.

Yes, it is a beautiful and very interesting job. We are operating within a highly complex setup of different stakeholders, societal interests and policies, which often involve a lot of tact and hitting the right notes. It is a real team effort working hand in hand with The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation and organizations such as the local foundation with its international board, the Finnish Guggenheim to Helsinki Association that support the project in many ways. And we have a lot of corporate partners and other organizations supporting us, so it's really starting to be like an eco system and a network.

It’s definitely not a nine to five job, but as with many people who work in Scandinavia’s cultural sector I strongly believe that this project will change our art scene entirely. Art means a lot to me personally. So I love the fact that I am able to play a role in paving the way for such a great opportunity for Helsinki, Finland, and the entire Nordic region. Right now I wouldn’t want to be in any other job offered to me in this world. (laughs)

As you already suggested, if one plans a high-profile project with radiance such as this one, one has to be aware of a lot of voices. Ever so often, projects of this scale start out with an uphill struggle.

Yes, that was also the case with the Guggenheim Helsinki venture. The project was initiated in 2011, when the City of Helsinki commissioned a feasibility study of building a Guggenheim Museum on an empty site at Helsinki’s harbor, next to the market square. The plans triggered some heated debates in the Finnish public about how it would impact Helsinki and the Finnish identity. Many stakeholders felt left out of the conversation about the concept, the site and other significant aspects. So when the City Board voted about the project’s next steps in 2012, the idea was actually rejected, albeit only by a single vote. It was by an extremely close vote, but it was still a ‘No’.

Today the picture is different. Although the future of the Guggenheim Helsinki project is still under discussion, it appears that the citizens of Helsinki are now embracing the project more passionately. What has changed along the way?

It was a real change management process, during which we all learned a lot about ourselves and about the Finnish way of doing things. Although Finland is a very progressive country, if it comes to architecture, design, and innovation, Finns tend to react suspiciously to ideas proposed from the outside. It requires intimate knowledge of Finnish culture to be able to enter into a dialog with the Finnish society and into the decision-making process on a political level.

The public had expected a participatory process when it came to introducing the project but neither the Guggenheim nor the City of Helsinki anticipated just how closely the Finnish people wanted to participate in the process. Despite the initial ‘No’ vote the Guggenheim team remained unwavering in their commitment to the project and were determined to adjust their approach in response to the needs and expectations of the public. As part of the realignment a decision was made to delegate significant leadership of the process to local organizations.

I have been the director of the Guggenheim Helsinki project since 2013 employed by Miltton, a large Scandinavian communications and PR agency. Miltton has been commissioned by the Guggenheim to lead the project locally, to act as a liaison among the different local organizations involved, and to moderate the public dialog. I had already been involved in the project’s early stages, but more in the role of a supporter and advisor, which provided me with first-hand experience of the challenges the project had been facing.

What were the things that needed to be adjusted to negotiate the venture more effectively with the public?

It was clear that we had to make this a community-led process, which implied extending our view to all potential stakeholders, including those who felt that their voice had not been heard in the initial stage. So we put together a plan to engage more effectively with this broader set of stakeholders and to take up each group’s concerns and expectations in a more constructive manner.

It was really about engaging with existing organizations, opinion formers, and all kinds of people who were wondering how the project would impact life in the city. We entered into a lot of discussions with these diverse audiences – from the harbor administration, to the urban planners, to directors of other cultural institutions and tourism offices, both in- and outside Finland, and to local countermovement organizations.

How did you manage to recreate a constructive climate for the project?

One of the obvious things we had to review was the site, on which the Guggenheim was initially proposed to be built. It carried a lot of baggage, as many projects had been previously planned on the site, none of which had moved forward. So we were looking for a new site to enable a fresh start, free of emotions.

We reached out to the public in all kinds of creative ways. For example, we ran a workshop where people could draw their imaginary museum. We took all these drawings and made a rendering incorporating everyone’s ideas. People were really engaged in that process, which made us realize that their concerns were less about the museum in principle, but about how it would affect the dynamics in the city and how one would be able to interact with the building. It was not cool logic, but based more on emotions. This insight was very valuable for us, because we began to understand that we had to be more concerned about the impact of the museum on Helsinki and Finland and that we had to become more transparent in the steps we would take.

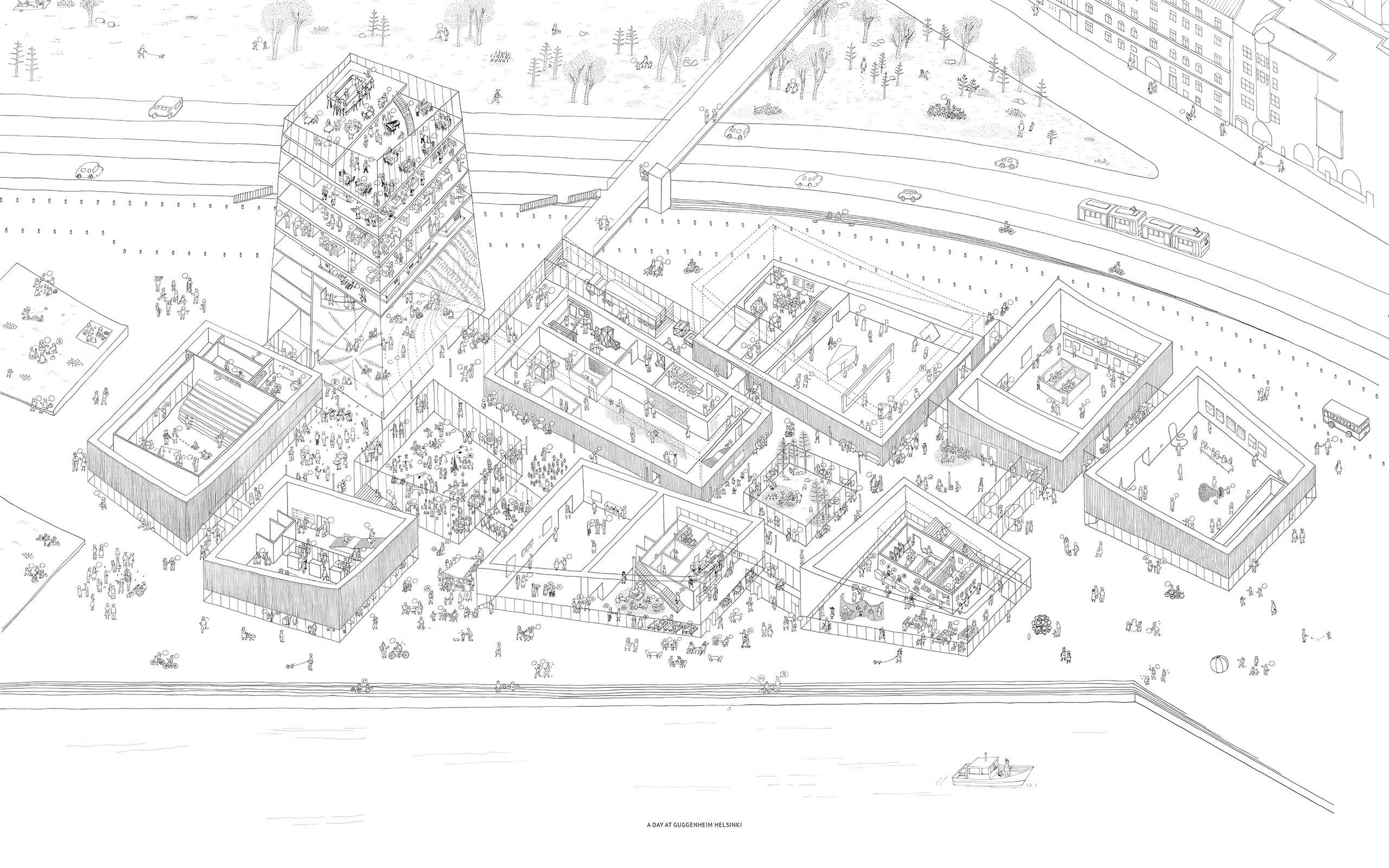

Courtesy of Moreau Kusunoki Architects

Courtesy of Moreau Kusunoki Architects

The architectural competition for the Guggenheim Helsinki has been remarkable in many ways and had a great influence on how the project was regarded from there onwards.

Yes, you’re right. It was an epic moment for the project. As you know, architecture has always played an important role in the Finnish identity, so of course the competition stirred up much attention. As one would expect, the building of a new Guggenheim attracted a lot of entries into the competition. But the number of proposals we ultimately received went beyond our imagination: 1.715!

What made the competition unique was the fact that it was very participatory and content-oriented. It set off discussions about the design of the city and its needs, as well as Finland’s design and architectural heritage, involving the harbor administration, the city planning department, the tourism board, lobby groups, and so on. Again it became clear that we could never have opted for a top down call and why we needed to have this open conversation.

After an open, anonymous design competition, it came as an absolute surprise to many that the winning design was not by one of the architect superstars, but came from a small French-Japanese architectural office.

Yes, that’s true. The winning architects were Moreau Kusunoki, a small two-year-old architect duo from Paris. Until then, it had been unheard of that a small firm such as theirs could win a project of this caliber. Their concept was chosen among the six finalist entries – by the way, none of the finalists were Finnish architectural firms, which probably also came as a surprise to many.

Moreau Kusunoki impressed the jury and the project team on many levels. Obviously this is a life-changing experience for the two architects and one could really sense their enthusiasm and commitment. They were very craft-oriented. Their entry included a wall drawing that Hiroko Kusunoki had executed by hand with an incredible attention to detail showing the future museum near the harbor. You could see a fisherman wearing a fisherman’s hat in a small fishing boat on the water. It was clear to us that they would be willing to go the extra mile in understanding how this building would fit into our world.

The idea of an open, anonymous competition was to open the opportunity to as many as possible. Although it was not intentional, the decision for a small architect duo, instead of a superstar architectural practice, completely changed the way many people looked at the project. It came as a reassurance to many that in this project some things were done differently.

Finnish people are very involved when it comes to architecture. How was the design concept for the new museum received by the public?

As you say Finns are extremely critical about architecture, because we live with the great masterpieces by architects like Alvar Aalto every day and we feel we have architecture in our DNA. Having said that, almost universally people loved Moreau Kusunoki’s design.

There is still an on-going debate about certain aspects such as the color scheme and the choice of some materials, but largely it was extremely well received. Very importantly, the architects have managed to build a great connection with the local community and they are committed to making the Guggenheim Helsinki a place that meets with people at eye level and can belong to everyone.

Finnish and Japanese share similar philosophies when it comes to aesthetics and functionality. Did the fact help that one among the architect-duo was Japanese?

I think what is embedded in both our cultures is an appreciation of nature, all things natural, and an eye for the human scale. Finnish and Japanese design aesthetics are very similar in that they are designed for functionality and maintain a connection to nature by the use of materials.

It was certainly not a criterion in the choice of the finalist, but it is true that some of the aspects that were most impressive in Moreau Kusunoki’s concept – the choice of materials, the attention to detail, and the genuine interest to integrate the building into the city’s vernacular – could be arguably linked to Japanese design philosophy and craftsmanship.

Helsinki could have invested in raising the profile for one of its existing art institutions such as the Kiasma, or Helsinki Art Museum. Why does Helsinki need a Guggenheim?

When the project came into being we were thinking about the whole of Nordics, not just Helsinki. The Nordics have a long-standing record of collaboration. Traditionally, we have always been stronger together. And, from a Nordic perspective, there is great potential to raise our collective profile as a destination for art and culture, in addition to architecture and design. We have a vibrant scene of talented young artists. Outstanding institutions like the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art near Copenhagen, or the Kiasma here in Helsinki, are setting high standards.

But this reputation does not tend to travel beyond our own region. We need to get more traction in the international cultural scene and become a part of the international art conversation. With the Guggenheim Helsinki as a beacon for the region, it would be possible to strengthen our commercial art sectors all across Scandinavia, including galleries, corporate collectors, and art fairs. To the degree the sector will grow new support schemes and other opportunities for artists from the Nordic countries will develop.

Could the Guggenheim Helsinki also serve tourism in Scandinavia?

Absolutely. Imagine, at Helsinki Vantaa Airport alone, we have approximately 4.000 travelers in transit, who don’t come to Helsinki on a daily basis. If we were to get a fraction of those 4.000 travelers to come to Helsinki, even if just for a day, that would make a huge difference. It is all about thinking in destinations. Looking at the project from a traveler’s perspective we already have amazing connections, a really cool hotel sector that is growing, and a very healthy bar and restaurant sector. However, people don’t come for the hotel, or the choice of restaurants. They need other reasons. With the Guggenheim, we could add a spectacular destination to the map in Scandinavia.

Arriving at Vantaa Airport the other day we couldn’t help registering the number of Asian travelers in transit. Also, here in the city, you see a lot of tourists from Asia.

Helsinki has a unique geographic position as a gateway between Europe and Asia. Travelers to or from Asia are definitely an important audience. The metropolitan area, Helsinki-Vantaa Airport and Finnair are very dedicated to catering to this segment. Asian tourists are well educated and very interested in art and culture. I imagine the Guggenheim Helsinki to take a flagship role, from which other cultural institutions in the region will benefit. We look forward to working with Swedish cultural institutions and tourism boards trying to convince them that it would be easy to fly to Stockholm or Helsinki, take the ferry over to another city, and then to continue St. Petersburg. All this can be done in four days.

The public discussion regarding the project continues. Cross your heart, will the Guggenheim Helsinki ultimately see the light of day?

I do believe so. We’re hoping that the government will make a decision about their investment in the fall. Until then, we have to wait and see. The conditions for the project’s realization are better than before and we are glad to have the support of so many local stakeholders. However, one should never dismiss the fact that there are a lot of decision-makers: foremost the City of Helsinki, which needs to make an independent decision about its role, and there are private funders, the local foundation and the Guggenheim in New York as well. Getting all these actors to commit to a single model and move it forward together is a complicated act. But who said it would be easy?

Courtesy of Moreau Kusunoki Architects

Courtesy of Moreau Kusunoki Architects

Courtesy of Moreau Kusunoki Architects

Interview: Michael Wuerges

Photos: Florian Langhammer