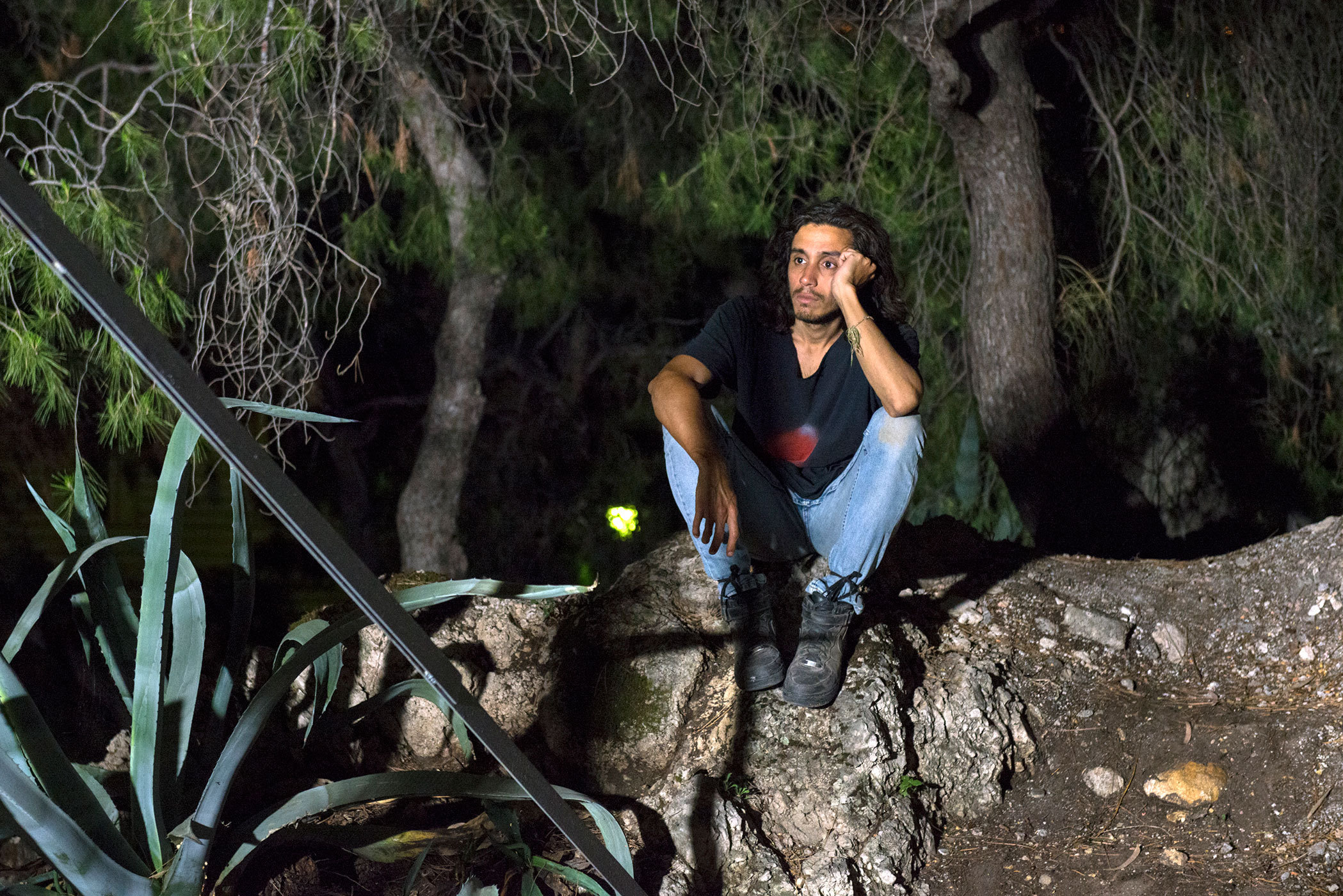

It’s tempting to mistake Adrián Villar Rojas for a convenient poster boy of contemporary art. The tireless dynamism with which he realizes often intensely photogenic projects of enormous scale, his savvy use of pop-cultural and historic codes and his youthful features make for great media content. Yet simply considering these surface attributes would require neglecting the richly sophisticated philosophical architecture upon which this Argentinian artist has built his work. In our conversation with him, he offers a glimpse into the substance of his ideas.

Adrian, normally we meet the artists we interview in their studios but that’s not so easy with you. Your practice leads you to work without the need of a studio space. Where has your itinerant way of working led you recently?

My general logic of movement has been from the Americas and Western Europe to Eastern Europe, the Middle East, Asia, and Oceania. For me that’s a process of deconstructing myself as a historical subjectivity. I come from a country with just two hundred years of independent history, which was bio-politically built by the nineteenth century liberal white European elites of Buenos Aires, who populated the territory with racially selected Western migrants and annihilated the native American population. This has led to a homogenization of the Argentinian people embracing the idea of being all white Europeans living far from our great-grandparents’ home in Spain, Italy, Poland, France, and so on. These roots are the mythological foundation of our national identity. Traveling for me has been a deconstructive tool to understand how far reality is from this self-inflicted image.

What led you choose this nomadic life, rather than settling in a studio in your hometown of Rosario or one of the international art capitals such as New York or Berlin?

I need to be in contact with as much of the geography of the planet as I am able to in order to absorb information directly. You cannot experience – feel, touch, think of – the “world” from a single location such as New York or Berlin. Every context I am invited to work in, demands absorption into that unfamiliar reality in order to understand and interact with it. We can neither go on facing our practice as a commodity equally valid for any place and time, nor as a universal subjectivity descending with its truth to specially prepared platforms installed all over the world, such as galleries, institutions, foundations, etc., for our comfort and self-assertion. My response to this deadlock has been full commitment to social, political, geographical, cultural, even geological ecosystems, assuming as much risk as I can to produce not a commodity but a process that mostly remains site-specific as an irreproducible experience. Though there is matter involved, I tend to think of the production of things as a byproduct of those mainly human-engaging processes.

Planetarium, 2015, Sharjah Biennial 12, Kalba, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

Courtesy the artist, Marian Goodman Gallery, New York/Paris/London and kurimanzutto, Mexico City

Photo: Jörg Baumann

Planetarium, 2015, Sharjah Biennial 12, Kalba, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

Courtesy the artist, Marian Goodman Gallery, New York/Paris/London and kurimanzutto, Mexico City

Photo: Jörg Baumann

From which point on was it clear to you that you wanted to become an artist?

In 1980, the year I was born, my mom was studying to become a doctor and my dad to become a psychologist. Before I was one year old, she would sit me next to her with pencils and paper to doodle while she was trying to memorize pharmacology or physiology books. Seemingly, I happened to be a pretty easy-going baby and would enjoy this doodling-beside-mum dynamic, so that – according to her – I could spend several hours a day drawing quietly, even silently.

Later on, how did you experience your art studies and your entrance into the art world?

From my first year in Fine Arts, at the Rosario National University, a free and open public university in my hometown, I knew that what I was taught to produce, so-called “contemporary art”, would – and should – not last forever. This was a very early and intuitive concern. With time I realized that the only sculpture I was really interested in was the human being. Nothing will endure, so we have to look at existence from its radical end. My practice began to move towards the idea of disappearance. I tried to watch things as if I was an alien sitting at the end of any symbolic production: an ontological entity that would grasp other entities with total impartiality and emotional detachment, and that would set itself to rewrite the world from this innocent tabula rasa, yet simultaneously monstrous, perspective. Playing this epistemologically fictional role, I would make suicidal and diachronic objects: things shaped, transformed or annihilated by time and non-human agency. The disappearance of the “sculptural” product would make the interface evident: the clay-plus-cement equation – predominant in my practice from 2008 to 2013 –, where clay is life before humans and cement the trace they will leave on the planet after fading away. I realized that in this broader map, “the artistic” happens as if by accident.

Can you outline a few of the issues you are approaching with your work?

I think that in Incendio, my first solo exhibition, which took place in Buenos Aires in 2004, the central problems of my practice were already present: the idea of collaboration, the problem of the representation of life before and after human beings, the radicalization of time into remote past and remote future, the end of the world as an epistemological fiction, the addition of layers of representation on existing representations in human culture, metalanguage, the problem of disciplines and of craftwork and of my own role as a director or montage editor. To these issues I should add a concern with technology as a human substitute, supplement and complement; with the relationship of humans with what they call “nature”; with politics inside art institutions to deconstruct stabilized signifying systems; and with commodity (“artistic objects” ready to be dismantled and shipped worldwide) as the normalized, capitalocene-submissive form of producing art in the twenty-first century.

Photo: Mario Caporali

You have described how your work does not require a permanent studio as it always develops specific to the site in which it is shown. This increases the importance of that location. How do you go about finding such a place?

‘Scouting' is a long first stage of all my projects. The number of visits I make before landing somewhere with all my team depends on the site’s complexity and on the ideas we are dealing with. This communication and exchange process with the context enables me to choose the site within the site. I aim to work with a degree of singularity that would be impossible without building this relationship with each institutional, cultural, social and geographical situation.

With your series under the umbrella title Theater of Disappearance you created a show that spanned from Europe to the U.S. including shows at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Kunsthaus Bregenz, Austria; NEON, Athens; and the Geffen Contemporary at MOCA, Los Angeles. What is the narrative that connected these exhibitions?

I see The Theater of Disappearance as a sort of deconstructive homage to Western art. As if I was mourning it from Greece to the United States. I tried to metaphorize and even depict some moments of the contingent, power-based building of its own genealogy, history, and heritage.

The installations of the Theater of Disappearance, like many of your works, tapped into a diverse network of references ranging from nature to archaeology, art history, and pop culture. What is it that fascinates you about these major influences?

The wide range of references is related to the epistemological fiction that guides my research: the alien gaze playing with humanity's symbolic noise at the edge of silence with no value scales but only commitment to a deep state of detachment. Around 2007, after my first experiments with this sort of radical otherness between Incendio and Pieces of the People We Love (Buenos Aires, 2007), I made this ontological decision to exile myself from this space-time, because I felt there was no longer anything to think of regarding art. Therefore following logical reasoning, I concluded: Since art has completed its cycle, we must think of it from the perspective of post-completion. If we are in a sort of “Duchampian limbo”, adding comments to comments, adding noise to noise, why don’t we go to when there is a great silence on Earth, and mourn art, or even mourn symbolic production itself? Therefore, every reference can be inscribed within this operation of radical estrangement.

The Theater of Disappearance, 2017, Kunsthaus Bregenz

Courtesy the artist, Marian Goodman Gallery, New York/Paris/London and kurimanzutto, Mexico City

Photo: Jörg Baumann

The Theater of Disappearance, 2017, Kunsthaus Bregenz

Courtesy the artist, Marian Goodman Gallery, New York/Paris/London and kurimanzutto, Mexico City

Photo: Jörg Baumann

The Theater of Disappearance, 2017, The Roof Garden Commission at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Courtesy the artist, Marian Goodman Gallery, New York/Paris/London and kurimanzutto, Mexico City

Photo: Jörg Baumann

The Theater of Disappearance, 2017, The Roof Garden Commission at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Courtesy the artist, Marian Goodman Gallery, New York/Paris/London and kurimanzutto, Mexico City

Photo: Jörg Baumann

The Theater of Disappearance, 2017

NEON Foundation at Athens National Observatory (NOA)

Courtesy the artist and NEON Foundation

Photo: Jörg Baumann

Often the pieces you create and the space they demand are gigantic. What is the dramaturgical role large dimensions play in your work?

For me scale is not a poetic gesture but the instrument to measure the intensity and complexity of my interaction with a context, in what I call a parasite-host relation. It also reflects how parasite and host deal with each other’s possibilities, desires and potentials. It is the material expression of a political negotiation with all the agencies involved.

The scale of your works limits the number of people who can afford to actually collect and display them. How does this aspect influence your work?

No doubt there is a paradox within my practice: In order to keep on existing it has to be somehow preserved, and at the same time it involves disappearance and the political rejection of commodification as represented by the capitalocene-submissive form of art practiced in the twenty-first century. This paradox is central to my project, it is unavoidable and demands a quite refined ability to deal with what I call the politics of art. By that I mean the ability to negotiate with different agencies the birth, development and continuity of a project that is essentially programmed to perish, mutate, change, or more widely to subvert all the logics of art collecting and preservation. One major part of my daily work is the design and redesign of these strategies. There is no protocol to follow in this subject, and it usually involves sustained exchange between the acquiring institution and my production office. However, the range of things delivered by my practice is wide and open, sometimes making it harder, sometimes easier to be processed by the circulating logics of the art field.

Could you name a few people inside and outside of the art world who have been influential for you?

My parents, for the collaborative way in which they built their love and family. Then my biological brother, Sebastián, writer and theater director, and my life sister, Mariana Telleria, artist, friend and former university partner. They are all decisive collaborators in my projects, fundamental readings, and my greatest inspiration.

We already talked about the string of spectacular shows you had last year. What are your plans for this year and how do you see your art developing in the near future?

I am currently working on a wide range of publications encompassing a long-term review of the path traveled so far. Considering that I come from a peripheral country that won’t have a cultural policy to preserve my work as a systematic corpus and that ninety percent of what I’ve done no longer exists, how would I go about building a retrospective view without capturing key moments of a work and life myself? For all the rest, I never talk about.

The Most Beautiful of All Mothers, 2015 14th Istanbul Biennial

Courtesy the artist, Marian Goodman Gallery, New York/Paris/London and kurimanzutto, Mexico City

Photo Credit: Jörg Baumann

The Most Beautiful of All Mothers, 2015 14th Istanbul Biennial

Courtesy the artist, Marian Goodman Gallery, New York/Paris/London and kurimanzutto, Mexico City

Photo: Jörg Baumann

The Most Beautiful of All Mothers, 2015 14th Istanbul Biennial

Courtesy the artist, Marian Goodman Gallery, New York/Paris/London and kurimanzutto, Mexico City

Photo: Jörg Baumann

Interview: Gabriel Roland

Photos: Courtesy the artist

Links:

kurimanzutto gallery