AES+F is considered one of the most successful and well-known Russian art groups. Despite their use of various media from installation to performance, the group is best known for their overwhelming multi-screen video installations of enigmatic narrative character. Behind the gloss of crisp and sharp images lies a survey of the values and conflicts of modern global culture.

To start with could you tell us what is behind your group’s name AES+F?

E: We started working together in 1987. At the time, it was just Tatiana (Arzamasova), Evgeny (Svyatsky) and myself (Lev Evzovich). Later, we came up with AES as an abbreviation of our surnames, when we realized that people had a lot of trouble spelling our names correctly. After Vladimir (Fridkes) joined the group in 1995, we became AES+F.

S: There was never a definitive moment when we decided that from tomorrow on we would be working together. It happened organically. There was an interesting commission from a theater that was offered to Lev and Tatiana. They needed someone for the team who knew book illustration and design. So we tried working together, we liked how it went and just kept going.

Previously to forming this collective you were practicing as individual artists. As you told us prior to our meeting, you are completely different persons. How do your different personalities and artistic interests tie into each other?

E: I think we are somehow similar in our artistic interests and tastes. But we are different psychologically and we have different skills. One of us is better at drawing, one is better at photography, etc. We do not compete with each other. Instead there is…

S: …synergy, a synthesis of our skills and combination of ideas.

When people read interviews with you, they usually can’t distinguish who of you answers the questions. It seems like you speak with one AES+F voice.

E: That’s true, especially in text-based interviews. We don’t appoint a speaker and don’t have any hierarchy that, for example, exists in film, even though our production is somewhat similar. In film, there is a specific hierarchy with a director, a producer, operator, screenwriter, and so on. We do not differentiate intentionally. It is both a strategy as well as some divine intuition, when all of us simultaneously have the same thoughts.

You have become quite successful with exhibitions around the world and participations at the Venice Biennale and the Manifesta among others. Can you talk about some milestones along your way of reaching such international acclaim?

E: There were two moments. The decisive moment was the Islamic Project in 1996, which received a lot of public attention and created controversy in the international media.

A: The project was intended to be quite provocative and politically incorrect in regard to Islam and reflected the Western Islamophobia. We created digitally manipulated images of famous landmarks and tourist destinations, making them look as if they were taken over by a radical form of Islamic culture.

S: The Islamic Project was presented as a “tourist agency into the future” on the main commercial thoroughfare in Graz at the Steirischer Herbst festival.

E: It caused a lot of controversy around the world, but with the events of 9/11, somehow we were hailed as “prophets”. This doesn’t happen often, but sometimes it does.

S: It was kind of pure artistic intuition, which was confirmed when reality caught up with the artwork.

E: And the second success was at the Venice Biennale ten years later, in 2007, when we represented Russia in the Russian Pavilion with Last Riot, which introduced the aesthetic of a new work cycle. In retrospect, it was one of the first projects that defined post-internet art and all the issues related to it. After that we had a number of successful projects, but the ones mentioned were the main impulses that propelled us forward in our career and earned us a certain reputation internationally. In both cases, it was very unexpected.

What can you tell us about your Mare Mediterraneum project which was shown at the Manifesta12 in Palermo in 2018?

E: Mare Mediterraneum deals with modern Europe or the Western World, migration, and cultural osmosis to oppose globalism or the Westernization of the world. In this scenario one no longer finds McDonald’s everywhere, but cultures formerly considered peripheral are being brought to the West. Such complex processes and this sense of paranoia and anxiety that is emerging around us are issues we generally like to work with.

S: The history of Sicily is closely connected to the ancient process of human migration, which never stopped. The Mediterranean Sea has always been a main axis of migration of large groups of people to or from Europe. Now we are witnessing just another chapter of it. That’s why, for a politicized topic, this startling form of gallant, elegant, erotic porcelain that talks about fragility of these civilizational processes and about some other aspects, gives the viewer who is used to certain types of artworks and discourse on this topic, a chance to see it from another perspective.

Palermo is also the site of a new project of yours – the opera Turandot at the Theatro Massimo.

E: We have reinterpreted the famous opera by Giacomo Puccini in collaboration with the Italian director Fabio Cherstich. Our version takes place in the Beijing of 2070, the capital of a Global Empire. We created a utopian city of bionic architecture, where the cruel princess Turandot reigns.

A: We introduce the idea of techno-feminism with a totalitarian touch.

E: The project deals with some of the topics that are central to our work: concepts of the future, feminism, post-feminism, and fake news

Do you actually pursue other projects individually as well? Or is AES+F consuming all of your time?

S: We only work as AES+F. Our practice is quite extensive and requires a lot of energy from everyone.

With your enigmatic video works you have created quite a distinctive filmographic style. Could you tell more about how a new video work comes into being?

E: Up to the moment we shoot, there is no script, however we do have a concept and ideas about certain episodes. We use storyboards or mood boards which provide insights into the main scenes. Mostly we make text notes rather than sketches. Some aspects are similar to film and advertising, like the casting, which is very important. The last one, for example, we did via Facebook. Another key aspect that differentiates our process from filmmaking is that the period of shooting is very short, taking up just a couple of weeks in a rented pavilion. Sometimes we use Chroma-keying, (a production technique for compositing images or video streams together based on color hues, also known as “blue screen” or “green screen” technique).

How do we have to imagine the actual production and interaction on the set?

E: We often shoot the human characters individually, then edit and assemble the footage later during post-production. It is typical for our human protagonists to “meet” only in the virtual space, where they might also encounter virtual characters. That’s why post-production – where we actually make the frame, as opposed to conventional filmmaking, where typically the frame is made on the set – can take up to a year. In large projects, it may even take up to two years.

In your video installations you work with extremely wide screens that can span up to 20 meters or so. What is the dramaturgic idea behind this?

S: It is extremely important to us to put the viewer into a state of full immersion. To overwhelm the viewer with more than they can process is a conscious decision that evokes such a state. Plus, it is part of our artistic language. We had used this approach for the first time in Last Riot and have since then studied its effects.

F: The viewer must be a little uncomfortable, not in the sense that they must be uncomfortable standing or sitting, but in the way that they must be alert and compelled to move. We want to avoid the comfort that exists in film, where we eat popcorn and look at a screen. Instead, we are forcing constant participation and movement, which results in a more conscious experience.

A: The “inconvenience” of viewing the storyline inevitably touches the viewer in an awkward way and may also evoke a sense of “guilty pleasure”.

S: It can be compared to real life, where you are never in a position to take in and process every piece of information around yourself. That fuels the desire to watch our video works again and again because, each time, you may discover something new.

You mentioned that the actual scenes only come into place during post-production, which distinguishes your work further from the conventional cinematic practice.

S: Technically speaking, it is not a video but a sequence of individual photographs. Each scene is animated and later combined in post-production. It provides us with a lot of flexibility, and variability. Then comes the rendering of the shadows, color correction, and the creation of the cohesive frame.

E: Our approach is grounded in the fact that a photo camera has a higher resolution than a video camera. That’s why from animated photography you are able to create a close-up or portrait from a larger scene. Our aesthetic is completely different and avoids the aerial perspective, (which, by blurring objects, creates the impression of depth and distance). Objects in the background have the same sharpness as the foreground. It’s important for us that the aesthetic retains the characteristics of the digital, the artificial.

F: We deliberately don’t have storyboards like in film, by which an operator would build a picture, so we can improvise on the set. We may decide to put two actors together in a scene that we hadn’t seen side by side during casting. The same possibilities arise during post-production, when we do the editing. This gives us a lot of creative freedom and space to play

In your video narratives one encounters a lot of fabulous creatures in mythical settings that are often charged with religious symbolism, such as in "Inverso Mundus". Can you explain what we actually see, how can we read or decipher what is happening?

E: Recently we spoke with (the French art historian) Jean-Hubert Martin in our studio: He said that, for him, all art is religious by nature. This idea, which seems obvious, is not prevalent in the contemporary art world. That’s why this religious subtext that you mention is transformed into an overt message by the viewer, into her or his own ideas of the sacred or religious or maybe even into something anti-religious. Inverso Mundus is rather a medieval carnival based on contemporary material. But like any carnival, it involves an inversion of meanings, including religious ones, when they become repressive.

In the Feast of Trimalchio, another work of ours, we reference biblical scenes such as the crucifixion as a juxtaposition to contemporary concepts of narcissistic enjoyment, or consumption, which takes the role of a quasi-religion. So, I would say we are probably more concerned with contemporary quasi-religions, or secular religions.

S: This allegorical aspect is present in our other works as well…

A: … but without didactics. We do not really manipulate the viewer. To speak frankly, there are things in the world that confuse us or make us doubt, pose questions for which there are no answers. We take this and show it to the viewer, and also to ourselves. The interpretation of the scenes is always subject to the previous knowledge and personal experiences of the viewer.

Is there a common misunderstanding about your art or some form of criticism that you have picked up from the public which you would like to rectify?

A: I still cannot agree with the opinion about our work which formed in the early 2000s, that we are concerned with glamour. That’s not what we do. There’s a visual reality of our existence. It oozes from everything in life, from the virtual space. Not taking that reality into account is impossible. As an interpretation of our aesthetics, glamour is not a suitable word.

Some people were crying, whilst watching "The Feast of Trimalchio". Have you ever personally experienced this kind of power exercised by a piece of art?

E: No, but I am profoundly impressed by Baroque painting, by Caravaggio.

F: When I was 18 years old, I visited the Tretyakov Gallery (an art museum in Moscow) and I found myself standing in front of some paintings for half an hour, unable to get away from them. Valentin Serov, for example, had this effect on me. When I became seriously involved in photography, it started to affect me in the same way. I remember returning to Moscow from the army service and visiting the exhibition American Photo, where I saw the last portrait of Igor Stravinsky by Richard Avedon: It showed the eyes of a man who is on the edge of life, and whose gaze is turned in on himself. I must have stood in front of this photograph for about forty minutes.

What conditions for working do you find in Moscow, which let you maintain the focus of your artistic creation here?

E: Until 2014 it felt natural to have our base in Moscow, because we were born and grew up here.

S: However, we have had experience working outside Moscow, for example for shootings in Cairo and New York. We produced sculptures in Finland, Spain, and South Korea. Presently, we are working on moving our studio to Berlin.

AES+F, The Feast of Trimalchio, Still 2-1-08, 2010, still from 1-channel video, InkJet print on Fine Art Barite paper, 32 x 57 cm

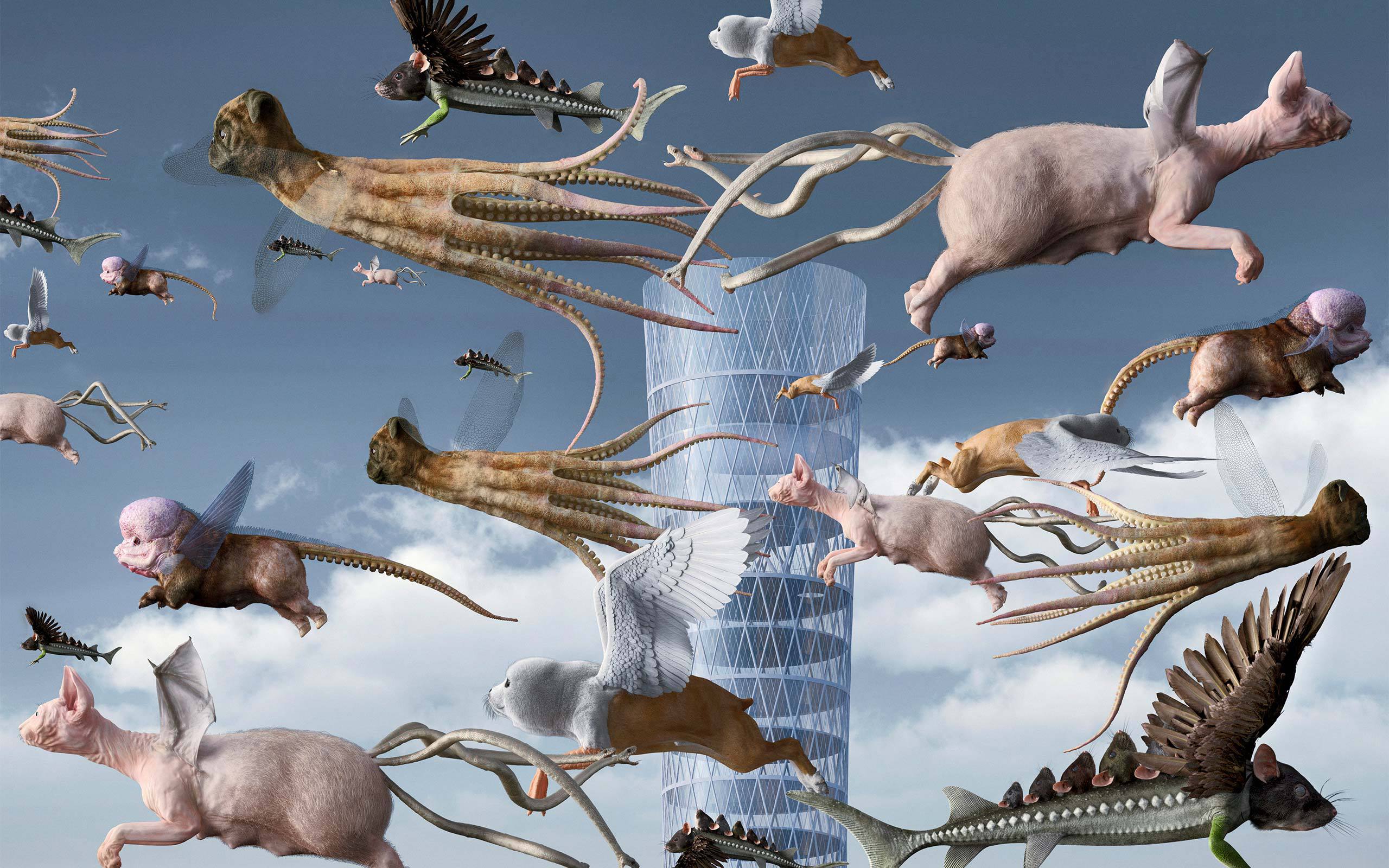

AES+F, Inverso Mundus, Still 1-02, 2015, still from 1-channel video, InkJet print on FineArt Baryta paper, 55.6 x 80 cm

AES+F, Last Riot 2, The Carousel, 2007, digital collage, c-print

AES+F, Turandot. Paradise, 2018, still from video

AES+F, New Liberty, 1996, digital-collage, c-print

AES+F, Mare Mediterraneum #1, 2018, hand painted porcelain, 35.3 x 39 x 23 cm

Interview: Valeriia Demonova, Florian Langhammer

Photos: Alexander Yakovlev

Links:

AES+F

Galerie Nikolaus Ruzicska, Salzburg

Triumph Gallery, Moscow

Anna Schwartz Gallery, Melbourne

Galeria Senda, Barcelona