Anna Titova and Stanislav Shuripa formed the “Agency of Singular Investigations” (ASI) in 2014 with the aim of taking a critical look at history, memory, and other connections between the past and the present. Their projects unfold as constructed situations where fiction becomes fact through exploring the documental. They work with reconstructions and originals, images and events to question acquired and seemingly truthful historical knowledge. Born in Russia and once based in Moscow, they now see themselves as a nomadic transnational “research & reflection” unit.

Anna, Stanislav, speaking to you as artists of Russian nationality who are not based in their homeland anymore, one burning question concerns your view on intellectual freedom. How did things change after February 2022 and the start of the war in Ukraine?

Anna (A): The problem is not only the lack of intellectual freedom; the whole reality crumbled. The war destroys not only lives, but also social connections, the public sphere, fields of cultural production, minds, emotions. If there’s no freedom, many things cease to make sense.

Stanislav (S): There is this specific kind of subjectivity as well. It feels as though – through the means of today’s digitally enhanced reality – some element leaked all the way from the totalitarian era and infected mass media. “Traditionalist” rhetoric, propaganda and censorship try to induce blind faith in the dominant mythology. The abuse of the communication media destroys the depth of reality. According to the official view, today’s world is quite empty: almost nobody is worthy of interest, friendliness, or recognition. It is such a stark contrast to the vibrant reality of the 21st century that happens outside this hermetic propagandist flat universe.

How does the Agency of Singular Investigations (ASI) deal with this perception?

A: We’re looking at the grey zone between facts and fiction, to find knowledge of the past. Lately, the conflicts between fact and fiction accumulated, the grey zone became successively populated by chimeric creatures like “alternative facts”, “fake news”, “post-truth”...

S: We both grew up in a different world. We had the feeling that things were getting better, freer, more complex: expectations of a brighter tomorrow had been part of cultural landscape since the 1980’s. This has changed, and history now looks enigmatic: how come a country rejects its humanist cultural traditions, its hopes for wellbeing in favor of a corroded myth of conquest? This might be why our work is about attempts to understand the meaning of history.

A: The result of our reflections is always some visually formulated narrative that unfolds in space. Founding ASI in 2014 was an answer to the historical challenges that we faced.

It was the year of the Annexation of Crimea. Did this political development spur you into action?

A: We felt the need to rethink this new reality. Everything became ideologically saturated, nothing seemed apolitical. We were in a new, darker and unpredictable reality. In this new post-2014 times, images became battlefields, language itself was mobilized to be a weapon of neo-imperialist politics. Since then, public language keeps mutating, it even started to sound different. So we felt the time had come to experiment with alternative visions, a kind of counter-language, creating spaces for social engagement. We started to think of our practice as mapping the way out of the darkness.

As you mentioned, both of you had been working as individual artists before ASI. How easy – or difficult – is it to work together?

S: If there is an idea that we both like, the work takes place in a kind of lab that we continuously refer back to. Our projects often consist of various parts that are interconnected in experimental ways. Each of our work is like the beginning of its own world made out of an intersection of stories, subtexts, objects and places. We may even discover other dimensions of our artistic attitudes when we work as ASI.

Tell me about your practice!

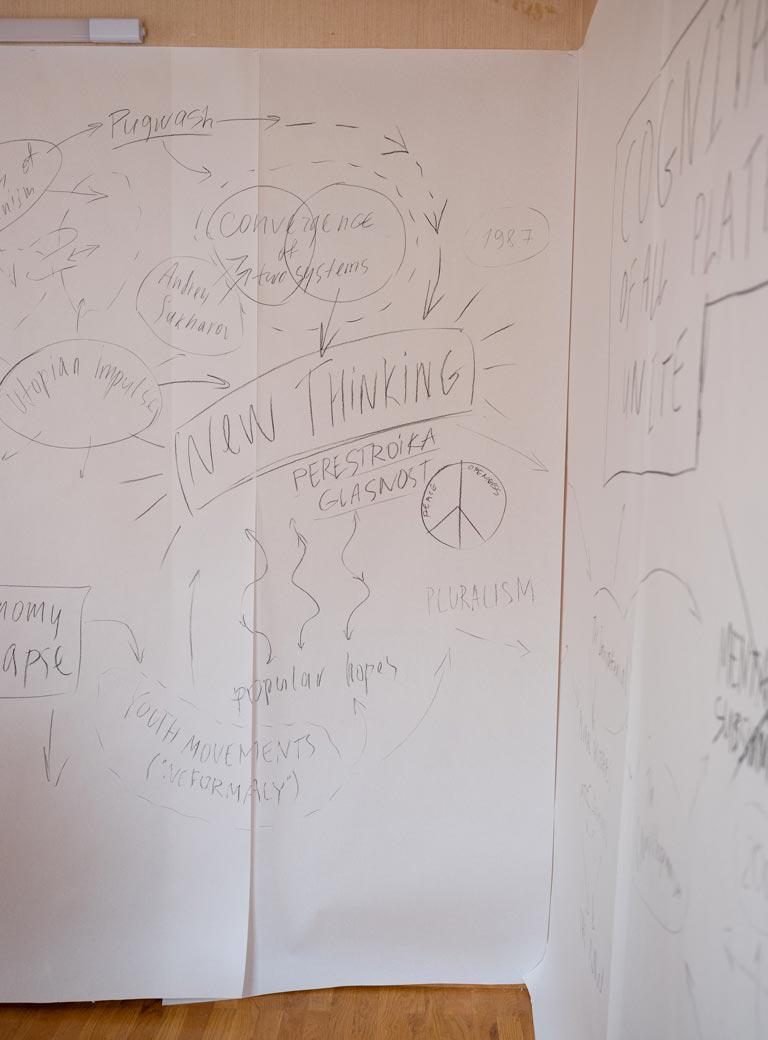

A: We start with an outline of a narrative, which evolves by itself while we try to map it. This map then turns into what viewers can see – it often takes the form of a text-based installation that may include documentary video, animation, performance, or other things. Flows of events might even lead to other stories. For example, in Flower Power Archive, we built an imaginary museum based on the documents of a secret society that stood for a parapsychological resistance against the Soviet regime.

S: We like to extend the idea of documentality to see what happens on its fringes. There’s an aesthetical dimension of the documental: a flickering between belief and disbelief, collisions of knowledge and imagination, alternating between fact and fiction.

Talking about objects: how can you visually express work that is so very conceptual and cerebral?

A: For us, ideas exist not as formulas but rather as clouds of meanings, pictures and moods. And it’s always fun to search for new ways to express an idea. At times it can be raw, bizarre and unpolished, because we are always trying to find different ways of engaging with the audience.

You mentioned your project Flower Power. Archive – exhibited in 2019 at the Moscow Museum of Modern Art – which is about the documentation of a secret society. Viewers could see documents, pictures, sculptures… but it was never clear whether you had made it all up or whether it was real. What was the audience supposed to think?

S: The process of understanding our work is part of the work, part of the message. The idea includes the aesthetics of oscillations between belief and disbelief in what you see and read. It is immersive: you read the documents and enter their reality, then at some point you notice that some of them seem to give you a wink; you might even find they are made up. There is a liberating feeling in this experience.

Does one need prior knowledge to get in touch with your work?

A: Our work does not require some predefined approach; it can be understood in more than one way. The “unexperienced” viewer is as important as the more “professional” one because the former can see the work in an unpredictable way. It is less about having some prior knowledge than about an openness to discover previously unknown meanings.

So your work is ultimately about getting people to think?

A: Thinking is a way of imagining. We explore the actuality of imagined worlds, and we construct them from components we find in the present. These worlds show potentials of the present, like forgotten futures of the past. We work a lot with historical archives. The state-controlled ones became less and less accessible in the past decade, the official version of history is reduced to poster-like images. If the past has now become a tool, we take this idea further to create “counter-tools” that inspire the viewer to see things in a more complex way.

In that sense, your work is historical but also political?

S: The political for us is about the interactions between weak and strong, small and big, about recognition, or how equality can coexist with inequality. What we do comes from the assumption of radical equality between facts and fictions, between copies and originals. These are the departure points for our work.

Can one still be a critical artist in Russia?

A: Well, punishments are severe, the witch hunt is intense. The general instrumentalization of culture might be part of a tendency to force artists to leave or be silent. You quickly hit a wall of invisibility that separates critical practices from what once was the public sphere.

Is there still artistic life in Moscow to speak of?

S: It has not disappeared entirely. Nonetheless, it resembles a blackout. While it may still be possible to be creative in such a situation: who wants to live forever under such pressure? Considerable parts of the art world seem to be in actual or internal immigration.

How do you deal with it?

S: Best is to stay away. Otherwise, you must exist within a closed environment. You constantly feel the contradiction between the nature of artistic practice – to communicate through showing – and the impossibility of public communication. This feeling alone is scary, but somehow interesting as it allows one to study previously unknown Kafkaesque aspects of reality. However, it is difficult to sustain a semi-ghostly existence for a long time.

The Russian artist Oleg Kulig said that when confronted with censorship, there are only two ways to go: “lick or bite”. What do you think about that?

S: Sounds like from another era. Today’s reality is much more complex, it refers to the experience from totalitarian contexts. A few people still try to keep working on some semi-underground level. The key question is not even whether the art scene will survive, but rather how it could be rebuilt once this horror ends.

However, many people in the West seem to think that “good” Russian Art today must be activist or political. How do you feel about this?

A: Activism is important. But protest art does not go beyond the one image that you take, because literally five minutes later you are detained, and nobody will see what you did. And then nobody can approach you or question you about your work. Now it is mostly art for the cameras.

What is art about then?

S: It might be about many things. It can make you see better; it may light the world around you, it can make you stronger. Aesthetics always have a dimension of struggle, culture evolves through conflicts. Every image is a political entity because it wants the viewer to believe in something. Nowadays the question arises once again about what art can and should do. It is about becoming and remaining yourself – through changing.

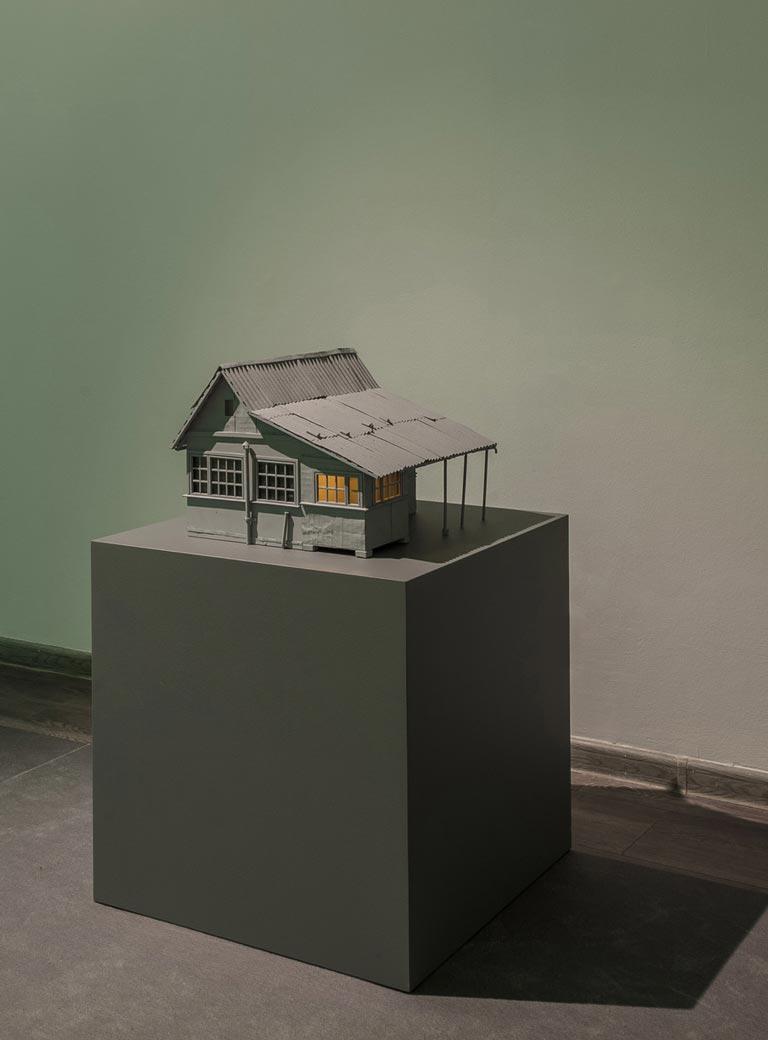

Century Beast, The Agency of Singular Investigations, 2019, Photo: Moscow Museum of Modern Art

Dacha, The Agency of Singular Investigations, 2019, Photo: Moscow Museum of Modern Art

Among others institutions, you are showing at the Vienna Secession. Above the buildings entrance, the famous words: “To each era its art, to art its freedom” are emblazoned. What do they mean to you?

A: Art is the image of time. As an artist, you try to figure out what reality and time are and how to show them. Our work is related to observing the traces of historical time, those – sometimes invisible – marks that history leaves. Art belongs to its time like a mark to the person who left it.

S: The image of one’s time is rooted in a one’s period. Obviously, an image lasts longer than a moment; time passes, and some art remains. Art can therefore connect experiences from various eras. And yet, you can’t invent the art of the future. Art can help to understand the present, but it is not a time machine. It’s another kind of machine, an optico-historical one: it helps you to see better through time. Which means that art is a form of intellectual freedom.

What is your work at Vienna Secession about?

A: We would like to show the results of our exploration of abandoned possibilities in the recent past. How could the present run of events still go another way, and not to its catastrophic end? How many paths to other futures have been lost – and what happens if we find them again? It is interesting to think about the present, prolonged, uncertain moment. We are working on a portrait of a frozen moment.

S: Our work should make the viewer travel from the so-called “happy end of history” – the world of yesterday – to the subjectivity of today’s mass media production and back.

That happy end of history – do you refer to the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989?

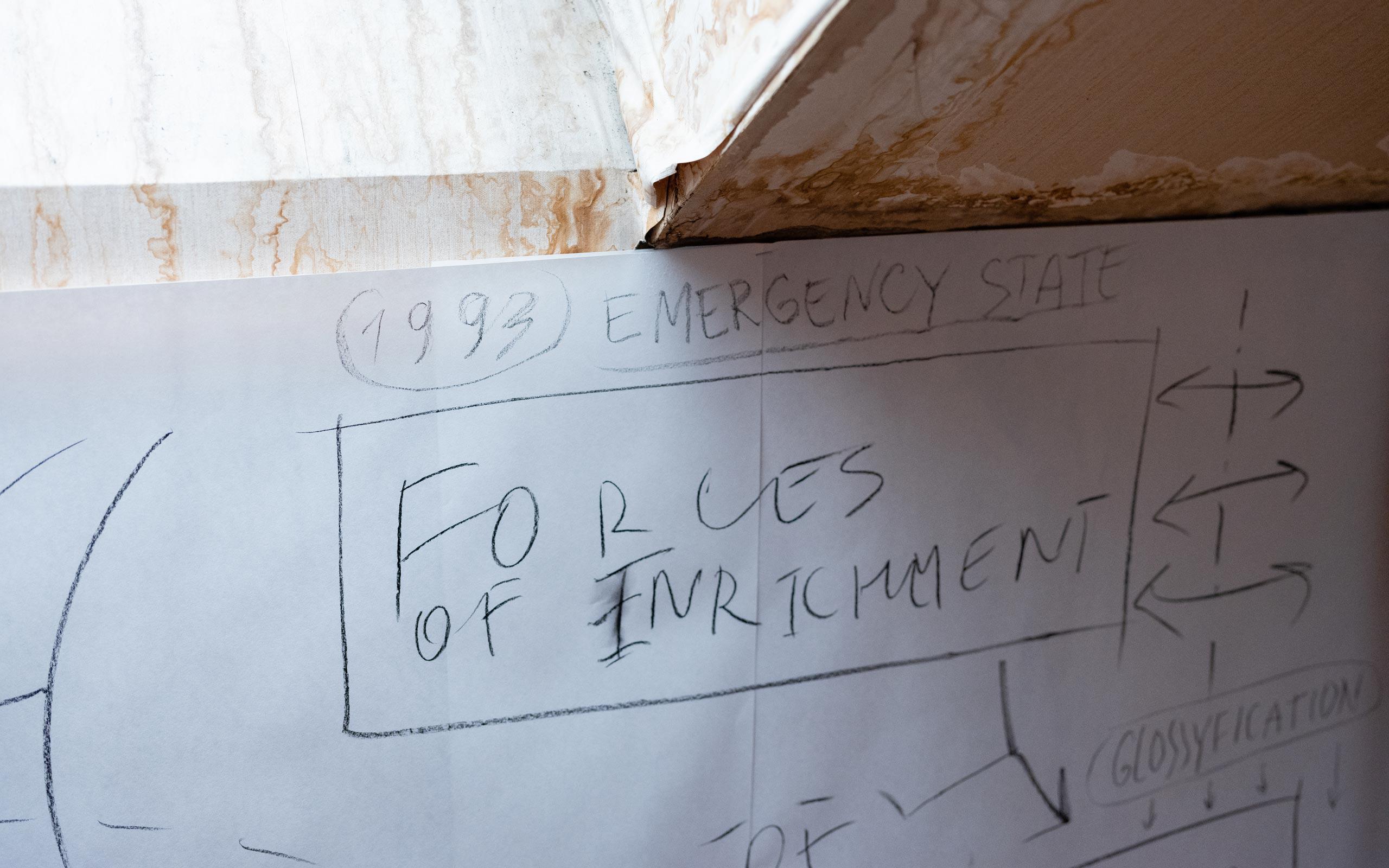

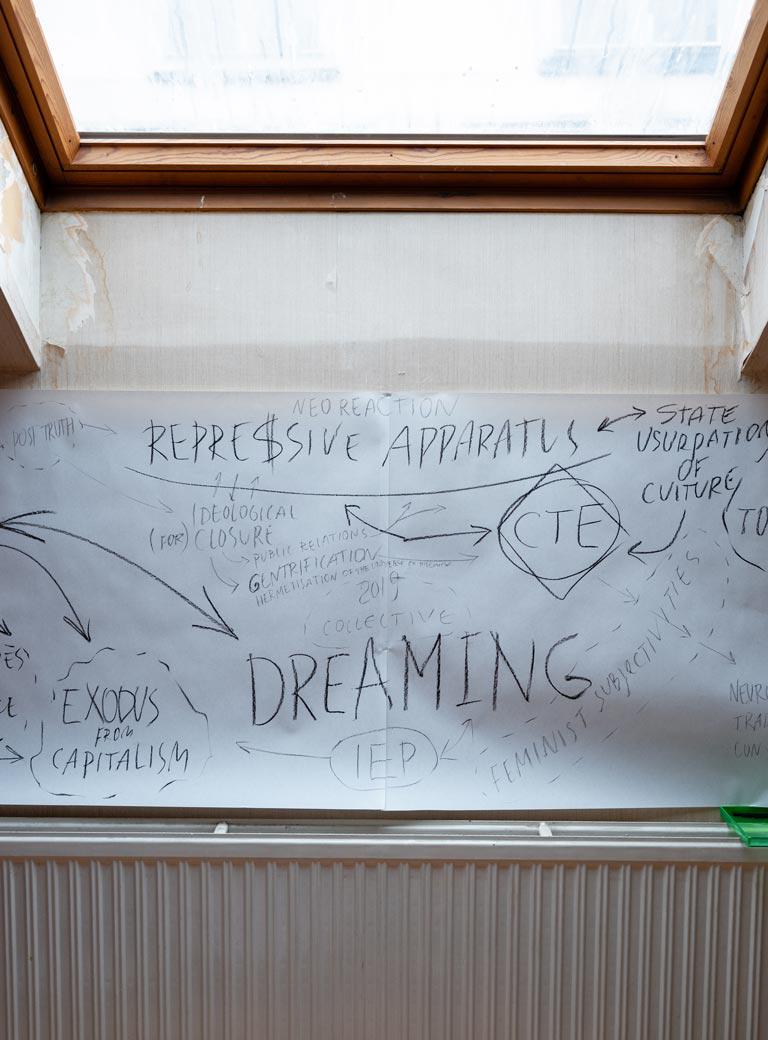

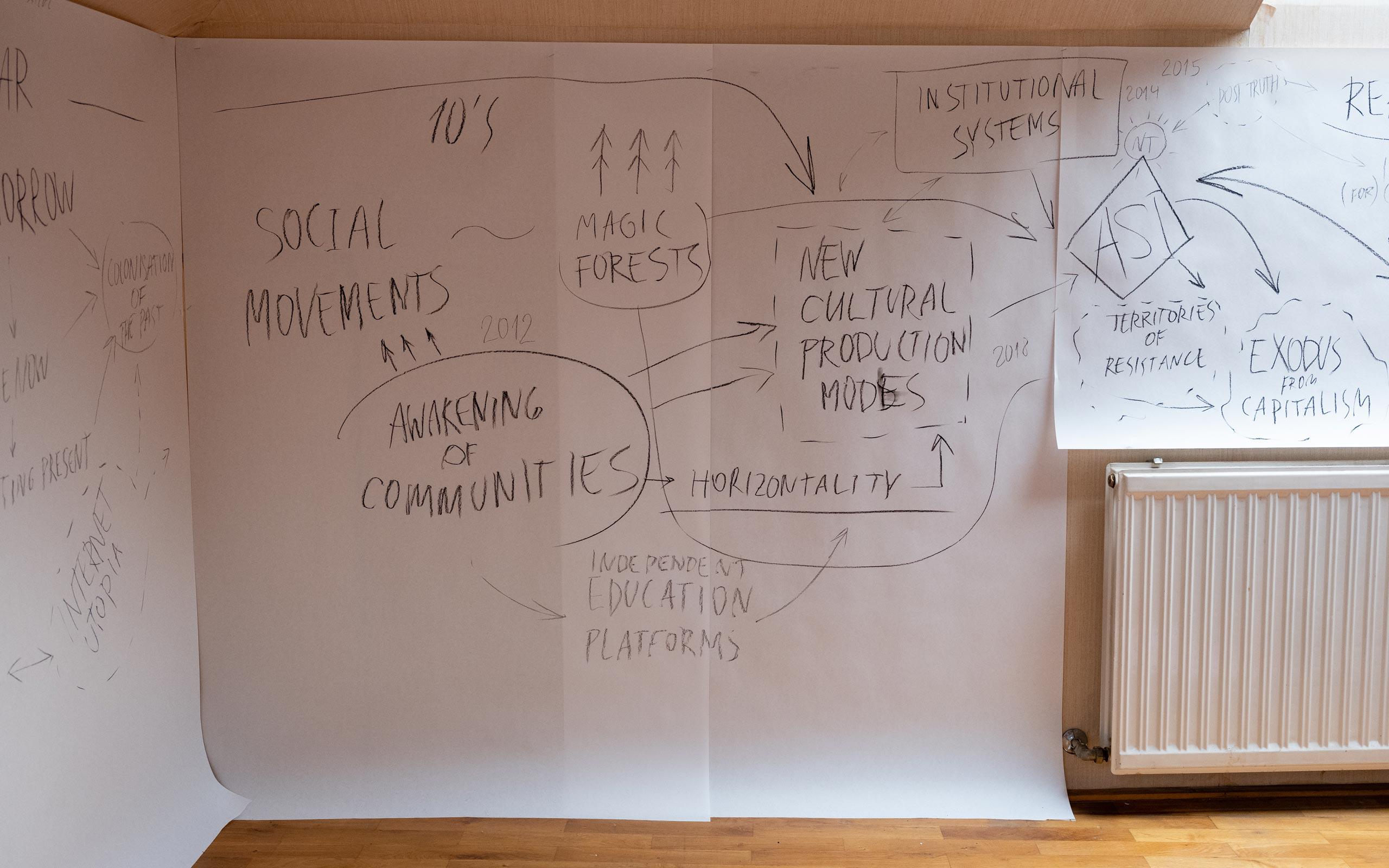

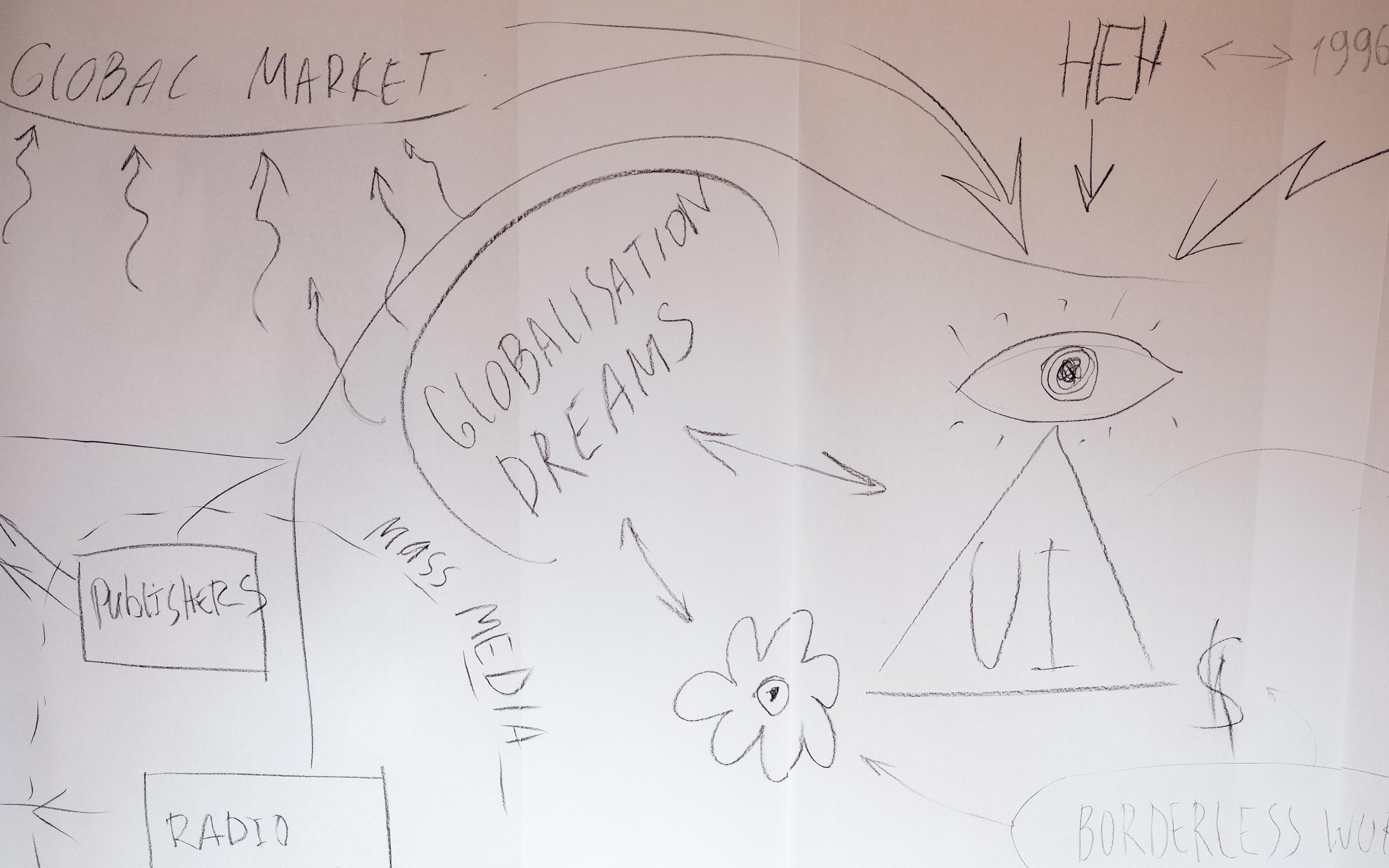

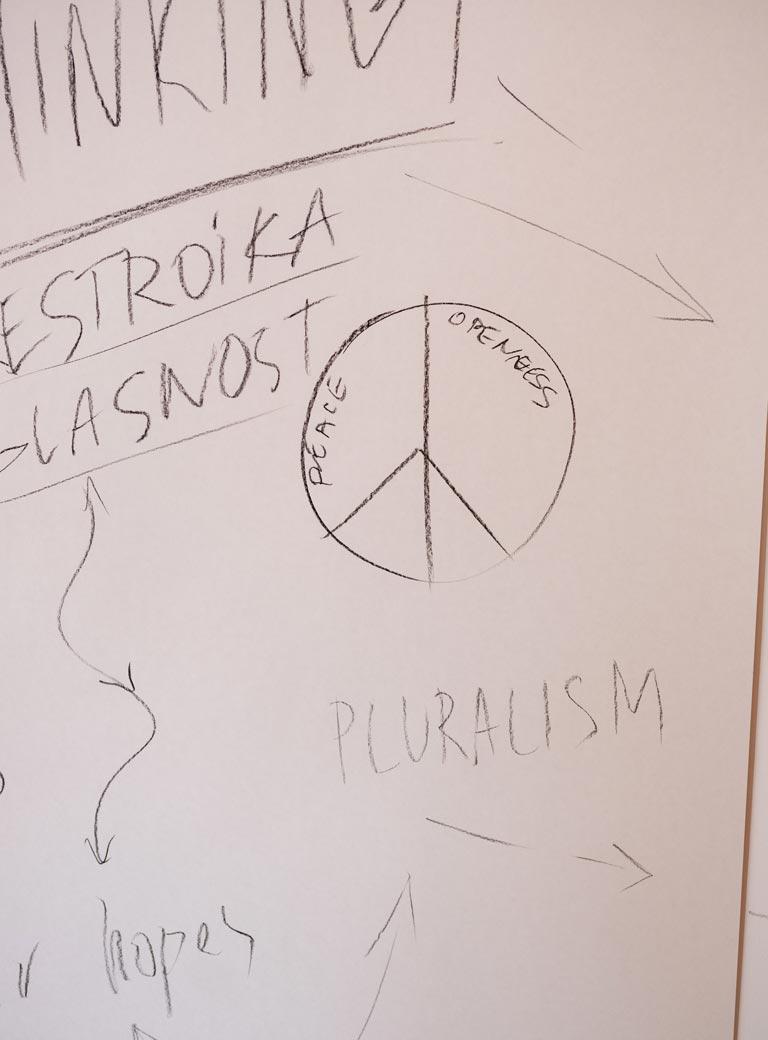

S: Back then, it was more than a simple curtain fall at the end of a play. The curtain came down with all those decorations, with the whole mythology…At the time, you could see many new futures, we felt we were part of a large liberatory movement. Today, we can see many characters and narratives of the past, like in a panorama of psycho-history. (He points to large mind map drawn out on paper covering all the walls around the room.) Here, we see a kind of landscape inhabited by the forgotten idea of Perestroika (New Thinking) which was fundamental in the 1980’s. New Thinking meant openness..

A: …and peace… We like to rethink the past to explore ways to a better reality. Maybe we will find answers to the secrets of the now in those forgotten dreams. Therefore, there will be a bombastic aspect to what we will do at the Secession (laughs).

Generally, you travel a lot – how does it influence your practice?

A: Travelling is a way to remain yourself, to sustain friendly and professional relations. It is a way to keep or repair some of what has been destroyed by war: ties, common grounds and exchanges.

S: We are interested in seeing our own work from other angles, in new contexts, through the eyes of various people. Travel is a kind of reflection.

Interview: Alexandra Markl

Photos: Christoph Liebentritt