A cold and dry quality radiates from the objects and mixed media assemblages created by Alex Ito in his studio in Queens. Chrome and other smooth surfaces, found objects, and aesthetic compositions convey historical imagery evoking positive suggestions of progress and technological achievement. Essentially, however, Alex Ito’s works bear witness to the concealed or marginalized stories of cultural eradication, practices of exclusion, colonialism, and violence that we accept in our culture in the wake of social change, material growth and capitalistic reproduction. He deconstructs and reassembles these histories, concealed in a sleek apparatus of cleanliness, and power revealing a truth so brutal that it is almost unrecognizable. His art implies that, although we will realistically never break free of our pursuit of growth and technological advancement, we should take care to deal with it responsibly and ethically.

Alex, how did you begin to create art?

I was lucky fortunate to grow up in an artistic family. My father is a skilled draftsman and has a natural talent with typography and calligraphy. I have an aunt who was a cel animator, an uncle who is a sculptor, and my grandfather was always making all sorts of creations ranging from dead animals and bugs preserved in poured epoxy, or wooden toys to entertain my cousins and me when we were younger. As I grew older, I became involved with graffiti. One of my favorite aspects, aside from painting, was the act of experiencing a whole different side to the city – a side that most people are not meant to see. From traversing various makeshift encampments, crawling under freeway overpasses and walking aimlessly through pitch black flood tunnels, I experienced the underbelly of Los Angeles. The palm trees disappeared into the night sky, the billboard displays of glamour seemed sadly desparate as did the empty late-night streets they so futilely illuminated. It was these experiences that created a safe space for me to challenge everything around me and to question the reality I had grown up so comfortable with. These experiences combined with sneaking off to various music shows and associating with the local surfing and skateboarding culture was a combination that produced a natural directive to my involvement with art. I was lucky enough at age of 16, to land a job at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) and I worked there until I was 18. During my time there, I saw solo shows by Dan Graham, Gordon Matta Clark, Emory Douglas, Louise Bourgeois, Cosima von Bonin, and many more artists. Seeing work at MOCA helped me articulate a lot of raw emotions and things I was dealing with at that time. This experience is what made me decide to apply to university and move to New York.

Do you have personal references in art history, fellow contemporary artists whose work you appreciate, or other people who inspire you?

While working at MOCA, I saw an exhibition of work by Emory Douglas made during the years of the Black Panther Newspaper. That work really struck me because of the power it held in its combination of both beautiful images and political acts. It was not only engaging but mobilizing within the format of printed matter that extended beyond gallery spectatorship. I was also really drawn to the work of William Leavitt and John Baldessari for their work regarding banality within the visual culture of every day life. Leavitt had a way of making the audience disassociate from the familiar with his wall facades, domestic interiors, and set-like designs. Baldessari had the amazing ability to codify emotion into pantone color blocks, cinematic imagery, and text. Both artists reflect upon the common and distill it into archetype or category while allowing for so much possibility through such intimate exposure. Most recently I’ve been drawn to reading about the work of Pia Arke. I stumbled upon her work while reading through magazines at a bookshop. The feature explored her intimate practice regarding indigenous identity and the violence of forgetting. I’m also always re-watching clips and scenes from films and video works by Apichatpong Weersethakul whose works dive into similar subjects as Arke, albeit from the perspective of quite different cultural backgrounds. His works remind me of staring into a fog where objects and beings come into and out of focus – fully present but remain enigmatic like a fading photograph.

Where and how do you typically start on a work? Is it the object that inspires the conversation or is there a statement that drives the art?

My practice is very driven by the fact that I need as much distance from the studio as possible. The artist studio – and sometimes the role of the artist – can easily become an echo chamber. This vacuum can cause work to become too self-referential rather than tying it to current social and cultural realities. I think because my work functions in a particular way, I need to be anchored to the real world. This can only come by inhabiting culture rather than escaping it within the studio. Having said that, most of the emotional and conceptual force of the work is generated outside of the studio and conjured up in lived space. I definitely become most inspired to create when reading on the subway, riding my bike or walking around the city. When I’m out in the world, a magazine clipping becomes a shape or a social atmosphere becomes a shadow. A silhouette can be authoritative while words can crumble to become as delicate as a pile of dry leaves. Everything becomes fractured and obscured when I experience them in lived space – almost like cinema.

Does this fragmented and contextual notion also influence the way you think about showcasing your work?

Yes, when I’m installing an exhibition, I look at it through the lens of cinema where images and effect collapse into a linear but fractured space. As much as content is important, I am very obsessed with atmospheric feeling, or the absence of feeling through alienation, and how that informs something as indexical as images and object-making in a gallery setting.

You often deal with inherently violent subject matter, from atomic bombs to Winchester rifles, where did that come from and what made you gravitate towards the theme?

From an American standpoint, these violent images are a part of pop culture vernacular. The first time I saw a mushroom cloud was in a Looney Tunes short. Westerns are a monumental archetype in global cinema. Both are narrative frameworks that have departed from their historical origin and now buttress the facades that surround our contemporary fictions. So I’m not necessarily drawn to them, but they are omnipresent in contemporary life. Unfortunately, I don’t have to reach very far to access these kinds of violent topics.

To me, your work is a wake-up call that brings to light the disguises of technological progress and their historically violent effects. In your opinion, is there a way to break free of this cycle?

That’s a question I can’t answer precisely. That is to say – it is not a simple “yes or no” kind of question. What does it mean to be free of something? Does it mean to be without it, exclusive of it? To imagine such futures would fall into a dangerous behavior similar to the misuse of drugs. An ailment exists and there is a cure. For social issues, this approach never works because of the elements of spontaneity, aberration and transformation that defy such scientific approaches. My practice is less a proposal for the future, but a reframing of contexts through the analysis of history and possibility. Future and possibility are similar but, in my opinion, are opposed to one another. A future is singular – as if looking at the path ahead through a measurement of time. Possibility exists in all directions as a form of potential. Humans have utilized technology since the first tools began to be used. Utility and instrumentality are a part of human social organization. We will never break free from it but we can learn to exist with it responsibly, ethically, and with care.

Are there examples of work with a positive attachment to technological progress? Or does every technological process come with a downside for you?

Of course there are. But positivity is not something that exists ex nihilo. Positivity is property and it has been monetized and is indebted to class/race relations. When we think of the great feats of the 20th-century industry, like medicine, transportation, or space travel, all of those practices have “progressed” at the expense of others, particularly marginalized communities. It is not to say that certain developments in technology have not helped the species. However, it is most important to understand what cultures and communities have been negatively affected for such progress.

Many of your sculptures seem to have an alien-like quality; chromed and smooth like the finish of some sort of technological device. Some also have areas of oxidation and rust on their surfaces, suggesting a condition of age. What are these objects and are they from the future or the past?

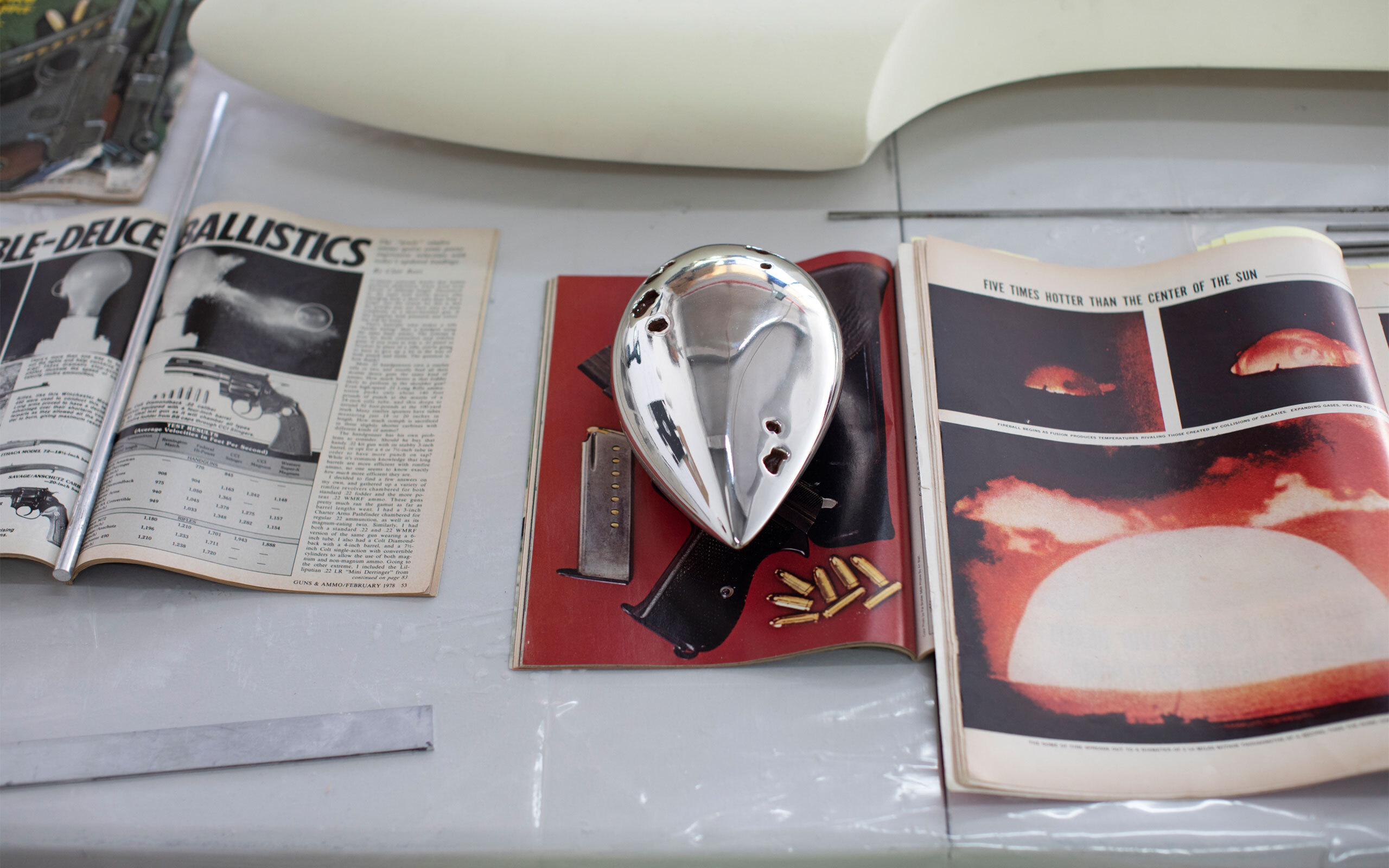

I began making these objects after reading Timothy Morton’s "Hyperobjects". For Morton, a hyperobject is something that has presence but can travel and outlast human measure. Some of the examples are storms, icebergs, waste, and plutonium – things that are seemingly everlasting in that they embody time outside of human experience. Although his analysis is mainly environmental, I wanted to think of this in terms of cultural memory and historical violence. I was wondering how objects retain experience and shape the future through their historical contexts and the cultural wavelengths that they emit. It brought me to think of family heirlooms and historically concrete objects like weapons and innovative technology. With my chromed sculptural objects, I wanted to imagine something that embodied both signifiers of the future – metal, dynamism, and cleanliness – but also embodied an element of temporality subject to time – the chrome. However, I didn’t want the object to be too recognizable for it’s utility, like a readymade, but to remain in an off-kilter state of familiarity. That unsettling state of being formless, to use French writer and philosopher George Bataille’s notion of it, is what allows the object to remain suspended in a state of disbelief of a current reality where culture is entangled with time and mutates in the bodies of media, tools, and technology.

In your perspective, are we approaching utopia or dystopia?

My goal isn’t to predict where we are going. I want my work to inspire opportunity of thought and criticism rather than define and frame the futures of others. Instead, I’m more interested to reevaluate the past and present culture through images, events, and technology and look at our dominant frameworks of language and rhetoric. In particular, I look at the cultural narrative of progress, which embodies both utopian aspiration and dystopian by-products. I find that particular narrative interesting because progress shapes the lives of others as much as it condemns them. This is because some of the core ideas of progress – growth, expansion, valuation – are also foundational to frameworks of war. Where there is growth there is also exclusion. Where there is expansion there is also erasure. Where there is valuation there is also dehumanization. With the ability to reflect upon these conditions within past and contemporary language, the work can hopefully inspire a spark of radical empathy.

A lot of your work deals with historical imagery, how do you source those and what is the creative process like?

Most of the imagery is sourced from magazines from the 1950’s to the present. I like using older magazines because of the idealism that was present at the time and how it manifested in things like World’s Fairs, mass production, nuclear arms race, and the space race. There was a different culture of belief that does not exist today, especially after events like Watergate, the War on Terror, and networked technology. In many ways, everyday life seemed much simpler and at the same time much more complacent to on-going social issues. There was a culture of happiness that I am fascinated with. I don’t hoard a lot of material at my studio but I love collecting these magazines. In most cases, I don’t use the images I like the most. They are special to me and sometimes I want to keep them for my own personal enjoyment. There is a feeling in these images that I want to translate into the work without directly appropriating the imagery. That’s why they just end up in stacks and boxes at my studio.

Along with popular history, you also weave in moments of your personal history that are specific to your Japanese-American heritage. Is it important for the viewer to align racial and cultural connotations specific to your personal life with your work?

Art has always had a colonial or anthropological angle to it. It asks makers to excavate culture or new metaphysical territory and present new languages from it. There is an emphasis on uncharted explorations and uniqueness in which the artist “owns” their subject although those subjects preceded the artwork and continue after it. With this, the subject matter an artist uses plays a performative role to buttress the structural integrity of an artist’s practice. Identity can function similarly and become integral to some, if not all, of the representation of one’s practice – particularly in the case of artists of color. I feel that most of the time any personal narrative behind the work is easily associated with dominant racial conversations – immigration, racism, language etc. It is always relevant and are all valid and important discussions, but can also create an expectation and preconceived cultural category to forcibly occupy and perform. With some of my most recent work, I have used personal ephemera, images and narratives surrounding the incarceration of my grandparents during World War II in internment camps in the United States. However, my practice does not use this family history to speak specifically to trauma or racial memory because I believe that is self-evident in its existence. I display those contexts because of my connection to it. They are a natural part of my life. The work is not meant to be a memoir but something we all share. A story is never just a story. It is something we belong to and that transforms through all of us. By referencing a story that I inherited, I have a unique vehicle to unfold my meditations on violence that can give a more complicated yet sincere window for how we frame life and participate in the subjugation of it as well.

Is there anything in particular that you’d like your art to stir in or do with a viewer?

Overall, I would like to advocate for a general refusal of what is presented as a singular reality or history. Especially in the age of information, it is important to use the tools and perspectives around us to strive against the common grain. Criticism is essential to this as well as the ability to exercise some restraint with our viewership and what we consume. When I refer to restraint, I refer to the ability to pause and to push against the impulse of spectacle. Spectacle, even more than ever, penetrates us everyday and visual art, as much as poetry, literature and critical thought, opens the opportunity to refuse the coercion of false fantasy. This fantasy is singular and linear – a windowless hallway in which to avoid the other and get lost within. But the wonderment of that fantasy is one of forgetting – forgetting the outside adversities we cannot or choose not to see. So what I offer is not a beautiful painting or an infinity room. All I offer are tools to refuse. Through refusal, we access a web of memory that is tangled, difficult, frustrating and, ultimately, filled with intimate life.

Lastly, what’s next? Is there something that you’re working towards or a dream project that you’d like to explore?

Since 2017, I’ve been slowly working on a video project that I will finally be exhibiting in New York in November 2020. The video addresses my family’s history with Japanese internment and nuclear waste practices in America. That will also be accompanied by some new sculptural and installation works. I’m really excited to be sharing this work as I haven’t had a solo show in New York since 2015. At the same time, I am terrified as the exhibition is scheduled right after the next presidential election in the United States. With the looming anxiety of Trump’s re-election, I want to make an exhibition that can cater to a potentially post-Trump landscape and be prepared for the potential of a continued Trump administration.

Exhibition view: You Promised Catastrophe, Zeller van Almsick Gallery, 2019

Needle In A Heap of Grease, 2018, Exhbition view: You Promised Catastrophe, Zeller van Almsick Gallery, 2019

The Gun That Won The West, 2018, Exhibition view: You Promised Catastrophe, Zeller van Almsick Gallery, 2019

Faded Virtue, 2018, Exhibition view: You Promised Catastrophe, Zeller van Almsick Gallery, 2019

Interview: Benny Or, Florian Langhammer

Photos: Katharina Poblotzki

Link: Alex Ito's website