Alexandre Diop is a Franco-Senegalese multitasking artist whose process is guided by experimentation and historical observation of our respective societies. Employing many different mediums including dance, music, film, and literature… He is best known for his singular work methods that occupy a zone between painting, sculpture, and relief, using everyday objects such as books, photographs, metal, and wood, as well as fire, and other elemental compounds like rust, and animal hair; Alexandre Diop’s permanent radicality pushes the public to a new experience of political and dreamlike systems through what he calls his “Object Images”.

Alexandre, how did you arrive at creating art? Is art something you have always been interested in?

Yes, I think so. Growing up in Paris, I have always been interested in culture, in the ability to communicate, to be in the position where you can think. But I wasn’t a child who drew at home. It all began with theatre classes. One of my friends in the neighbourhood was already at the theatre school, and my parents thought it would be a good idea for me to channel my energy there; I loved it. Later came sports and I played a lot of soccer. I was like every teenager, missing classes now and then, but I was also working to obtain good grades. And then there came music, I was always surrounded by music and it is how I really discovered art. First with classical Music. My mom would give me CDs of Chopin, and I would ask her to play them again and again. Then came Cesária Évora and later Hip-Hop. Hip-hop is really a big part of my life, my brother is a rapper, I used to rap myself and I still want to make an album of my own one day.

When did your interest for visual art emerge?

After experiencing theatre, sport, and music I was in search of a new tool of expression. Every time I’d come back from a party I started drawing. I also wanted to be a painter, but at that time it didn’t work for me. It was too much. But, whatever I did, in a way I have always considered myself an artist.

What does it take to call oneself an artist? Could anyone call themselves an artist?

I don’t care much. I’m not here to judge whether other people are artists or not. I think everybody should reconsider the word and its meaning, for me an artist is someone who has become empowered, someone free of, or at least aware of political conformances, someone who’s able to create as a form of language, a tool of communication. I’m not only an artist I feel.

Who else are you?

I am Alexandre Diop, which is the name that my parents gave me, but which is also how I feel I am. It contains a lot of things. I feel as a political activist, a natural joker, a clumsy acrobat, a lucky, sad poet, a boring writer and a not yet recognised philosopher (laughs).

What is important for you when making art?

First that I feel good, then I like to disturb more than to charm. Even though it might contradict my personality.

What are the ideas that you put into it?

I would say it really depends on the day! But I have a deep interest concerning the parameters, the origins, and the future of Humanity. The ideas I put into my works are the result of my being alive. My work is a reaction to life and the ideas are the reactivity of it. I would also say that I’m really interested in death and all the ideas alive around it.

You grew up in France with a mother being born in France and a father being born in Senegal. After being in Berlin you now live in Vienna. Where do you feel you belong?

If I go to Senegal, people think I’m white, yet in France, they call me black. If I go to Austria, they call me French. If I go somewhere else, they will call me Senegalese. It feels good, but not always. Ultimately, I belong to the world.

Before you came to Vienna you had lived in Berlin? Tell us about your journey.

After receiving my baccalaureate (bachelor’s degree), I moved to Berlin. I was 18 then. I wanted to go to Berlin as I felt that it was a perfect city for producing electronic music and becoming independent. At one point, I was 23 then, I found myself in an unhealthy environment and I knew it was time for me to leave. I was studying dance and scenography and context at UDK (Berlin University of the Arts) and also attended art classes. One of my friends, who is like a sister to me (Jessica Comis), was already in Vienna, and she encouraged me to apply for admission to the painting class at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, find a studio in the city, and present my art to galleries. I was selected for Daniel Richter’s painting class. But my goal was not to go to school to study, because I knew what I was doing already. I needed a platform to meet someone, someone who would believe in me and support me. After not even two months had passed, there was the Akademie-Rundgang (open studio day at the academy). There I met Amir, my manager. This marked the beginning of something important.

What is the intention behind your art?

For me art is a tool; I want my tools to be as efficient as possible…

How do you source the materials for your works?

I always get them from the area in which I currently live. I go around the city. In the past when I would go with my bag, people would think I’m a young homeless guy. Their response would be: “Man, this guy is crazy, he doesn’t even collect things he can resell”. Even gypsies, some of whom eventually became my friends, would be like: “What are you doing man?” (laughs).

What do you look for in the objects you collect?

I like things that express time, that express a certain reality, that speak of decomposition. I’m interested in what creates death, what creates time. So, I look for objects that have certain aesthetics, things that are quite rusty, quite ugly yet also elegant, that possess a nobility as I see them. In Berlin I would go around the city and find stuff that people had thrown away. I always have scissors or a box cutter in my bag with me. If I came across a sofa, for example, I would cut out some pieces of fabric. Sometimes I’d think (makes sniffing sound): “Will I really bring this to my studio? No, it’s terrible”. In our consumerist materialist society, people throw away things without any sense of waste. Me, I always see the beauty in discarded things. In my studio I have a storage mess. I leave everything on the floor, and I start to work right there on the floor. These collected materials are my colour palette so to speak.

Your work is often associated with the Arte Povera movement that emerged in Rome and Northern Italy in the late 60s and early 70s.

To me it is rather African Arte Povera (laughs). The Arte Povera artists used this term because they wanted to express a concept, and I appreciate that. But for me it is more about an African mindset, it’s about myself, about me as a human being. Even a European, who had nothing to eat during the war, found a solution how to give presents to their children. Arte Povera comes from this generation of people loving people around them, being in love with life while not having many resources, yet, still being very creative; too much comfort can kill creativity.

Speaking of which… One could say that Vienna is a pretty comfortable place to live and work in. How does it affect your own creativity?

I always had everything at home and I will always be grateful to my parents, they were not rich, but middle class, and quite comfortably off compared to some family relatives… But when I came to Berlin, I had to put some constraints on myself, because I knew it would be the way for me to reach the level of quality I was looking for. So, there was a time I made a lot of sacrifices and dedicated everything to my art, as I still do today…This piece for example I did in Berlin in a studio without electricity, heating, or even proper light conditions. It was an old brewery, totally abandoned that someone let me have free. I used to sleep there with two sleeping bags during winter, at minus twelve degrees, and no shower.

Was it a self-test on yourself whether you had what it takes to be an artist?

No, no. It was the only option. I had no money at that time so there was no other solution. My parents always taught me: either you do something fully, or don’t touch it. So I went for it! Now Vienna is a very comfortable city, but I make the sacrifice of working almost every day, to be very disciplined, so I think I deserve some occasional comfort; I have a shower now (laughs). Also, I can make a living from my art. It’s “au mieux” (the best) to be able to explore other dimensions of myself, such as being a leader, an example to others, and to be healthy. But when I work, I need to be in a state of struggle. I compare it to athlete-level sports, a certain level of determination and dedication are necessary in order to achieve your aims.

You already mentioned that, on your way to becoming a visual artist, you experienced other forms of cultural expression including theatre, dance, and music, which people have made an impression on you as the artist you are today?

I was influenced of course by Cheick Anta Diop, one of the writers who influenced me politically. I have always been inspired by my parents, my father Ibrahima Diop, and my mother Mireille Bille. By my little brother Anta Diop, that’s his rapper name, they inspire me to be, and to believe. I grew up in Paris around great people and have had access to so many cultures. I’ve travelled and lived in many countries from Asia to South America, North America to Europe. Artists from Basquiat to Giacometti, from Miles Davis to the Notorious B.I.G., from Dostoevsky to Muhammad Ali: all of these people resonate within my heart. I also have mentors, which include Robin Rhode, Mara Niang, and AA Rashid. And, of course, my friends… Michal Andrysiak, Phillip Gintz, Elies Douair, Conan Lorendot, Alessio Cannizzo, Marcelo Alcaide, Kennedy Yanko, Leon Krzysztof… and the ones I’ve forgotten. Life inspires me. I would say it like this.

Do you see anywhere in contemporary art where you would place yourself?

Hmm, I don’t really consider myself a contemporary art artist. But I always want myself at the top (laughs), I want to be the active and not the passive element! What we know as contemporary art was created after the 1960s, so it’s been in existence for 60 years! I do what I do. If you show my work to indigenous people in South America or on an isolated island I’m sure they will recognize some of the spirits they deal with (laughs). I think what I do is what we call expression, and it’s not time specific. It’s always been there.

The Western art scene has, quite recently, discovered the work of African artists, or those with roots in Africa. How do you see this?

I see this as history, modernity, but also hypocrisy… A lot of African artists are emulating what they think their career should be. Some try to live their own lives, others try to adopt a certain identity of what they should be… I always question this. Who wants to be defined as a static notion? I personally want to always be in motion. I want to be free from categorization, as James Baldwin said, “I want to surprise myself”.

Do you feel understood with your art?

I don’t care whether my art is understood or not. What’s important to me is that I know what I’m doing.

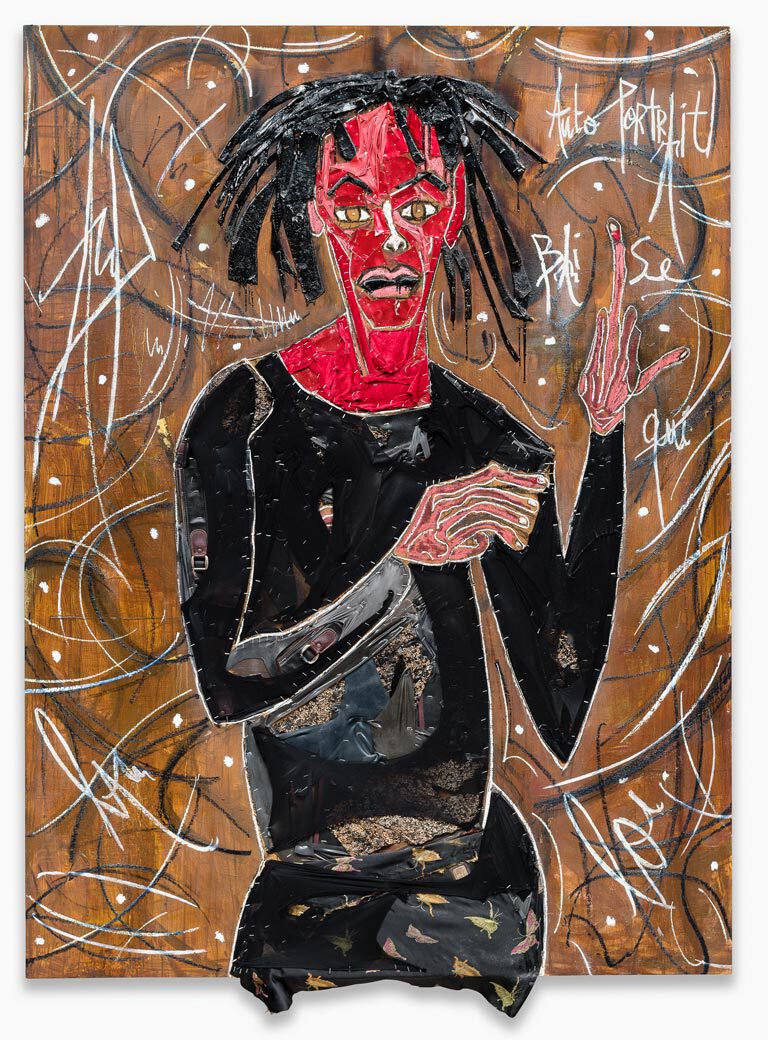

Alexandre Diop, 2021, Autoportrait of the young black diable at the age of 25, 215 x 160 cm, Collection Amir Shariat, Photo Credit: Jorit Aust

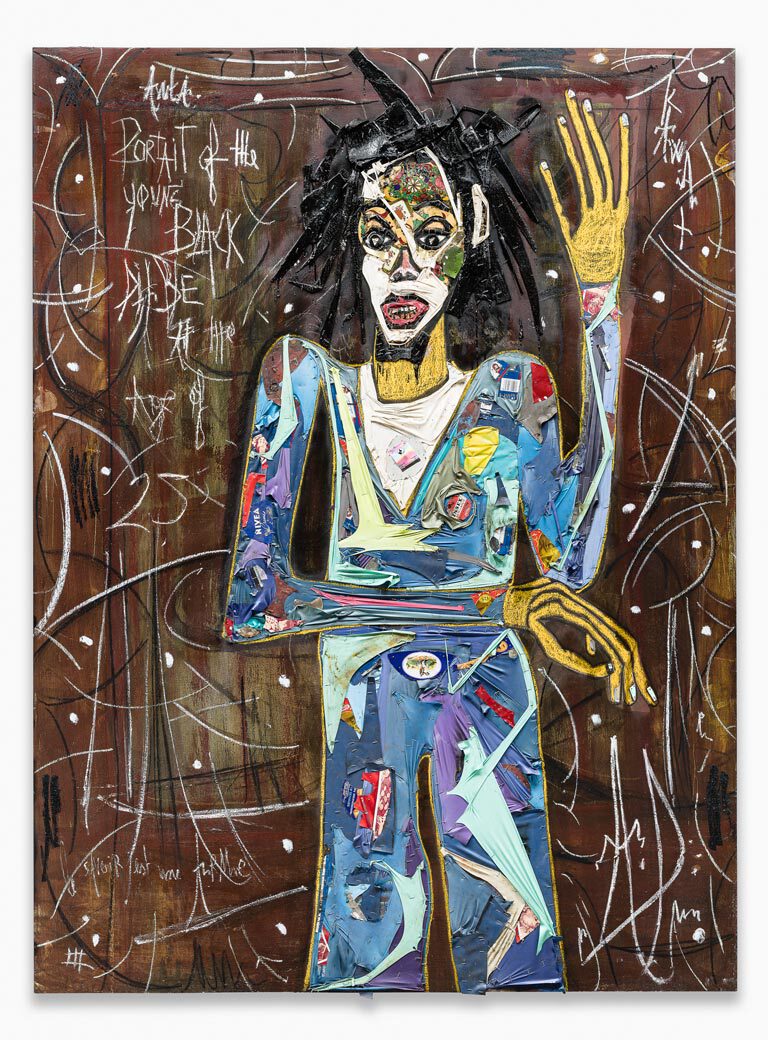

Alexandre Diop, 2021, Portrait de Mara Niang, 185 x 126 cm, Collection Amir Shariat, Photo Credit: Jorit Aust

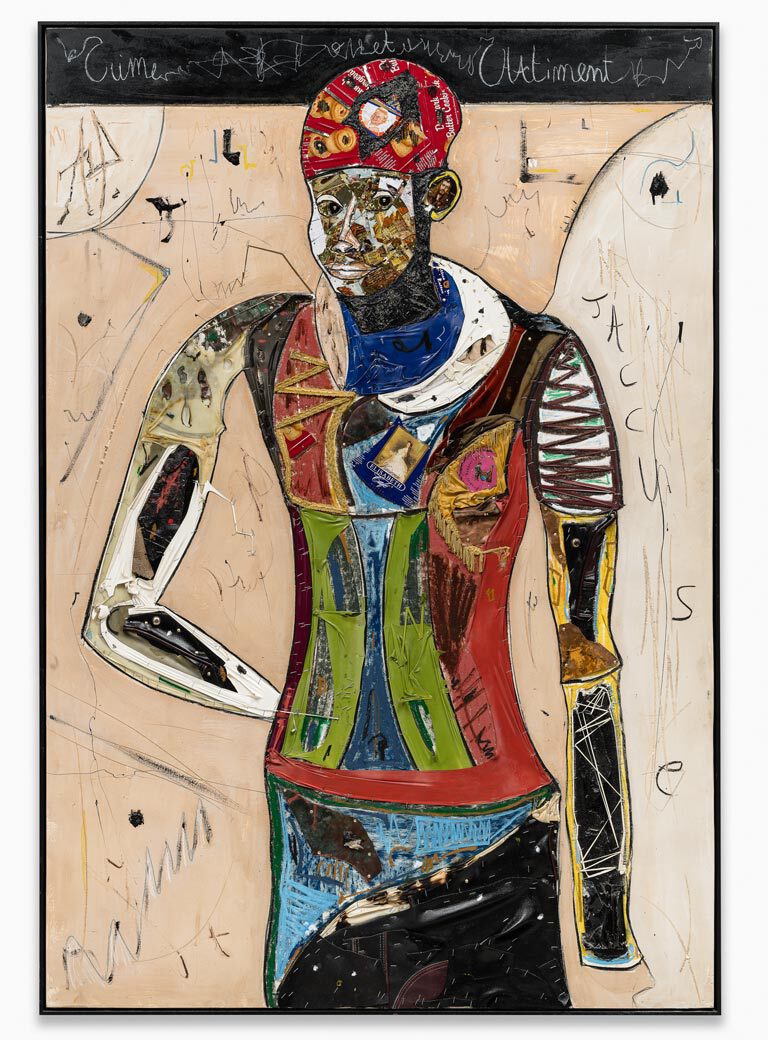

Alexandre Diop, 2021, Nelson Mandela, 252,5 x 185,5 x 4,8 cm, Private Collection, USA, Photo Credit: Jorit Aust

Alexandre Diop, 2021, Autoportrait qui baise la loi, 215 x 160 cm, Collection Amir Shariat, Photo Credit: Jorit Aust

Interview: Kristina Kulakova

Photos: Kristina Kulakova

Links: