Ali Cherri’s practice consists of video installations, drawings, sculptures and films. Exploring different geographies of violence, the Lebanese artist based in Paris often works with broken and damaged artefacts of history. Traumatic experiences of violence are not something to be hidden, but instead used as fuel for contemplating the future.

Ali, you have had numerous solo exhibitions worldwide, including Beirut, Paris, New York and London. Can you recall the emotions you experienced when you opened your first solo exhibition?

That exhibition took place in Beirut, which was important to me as it’s my hometown. It was one of the first times for my family to witness my work displayed in a museum in Beirut. Each solo exhibition feels like a new experience due to the new space and configuration. I am now exhibiting in larger spaces to showcase my work. But the excitement of the first time remains to this day, as you have to rethink how to investigate space from scratch.

You were born in Beirut during a period of Lebanese Civil war (1975-1990). Can you describe your life during that time and share how you developed an interest in art?

My only living experience at that time was from a city I knew, so it felt like a sense of normality to me. Simultaneously, postwar Beirut boasted a vibrant art scene, with numerous influential international artists from Lebanon shaping what has become known as the postwar Beirut scene. This period was my introduction to contemporary art. I did not attend any art school but worked a lot with other artists. Being in Beirut during this time was very interesting, as the city garnered international attention – we had educators, curators and museums coming for studio visits. Even before leaving Lebanon for my master’s degrees abroad, I was already very well connected to an international art network.

Was art a method you used to address the war in its aftermath?

I do not view it as a form of therapy, but of course it has been a highly intense experience. It raised numerous questions for me, particularly about the ability to narrate a story following traumatic experiences. Art played a role in providing answers, or at least giving directions, and creating space for discussions on how to rebuild a city in the aftermath of violence and war.

After leaving Beirut, you first relocated to Amsterdam and subsequently to Paris, which became your second home. What opportunities did Paris open for you as an artist, and what challenges did you encounter?

Moving to Paris was not a career-driven decision; it was more for personal reasons. I did not feel the need to be in Paris to create my art, as I was more connected to the international art scene than the French art scene. My exhibitions were mostly held outside of France, and my involvement in the local art scene happened much later. Living in Paris did influence my artistic practice, but the starting point from which I think about questions related to history, violence and city stem from my initial experiences in Beirut. Despite not being physically present there, I still visit Beirut frequently. Additionally, Paris can be somewhat intimidating.

Intimidating in what way?

It took me a long time to make a work called Somniculus, which was exhibited in Paris and then in other cities in France. This video installation was filmed in five empty museum galleries across Paris. I found it easier to enter the city from the museum as a back door; a safer place to question things that are related to the local arts. Paris has produced a lot of discourse with the great artists that live here, who thought about the city and produced images about the city. Finding your place within this general discourse takes time and maturity, and it's not an easy task.

Finding your place on the art scene in Paris, you’ve probably been asked many times to describe the art you make. Have you already formulated a universal answer?

My practice revolves around moving images and sculpture. The questions that interest me are related to the geographies of violence, specifically the landscapes where violent events have occurred and the possibility of narrating stories post-violence. Every time we look at different conflicts and different types of violence, new questions arise. These may encompass colonial violence, violence of collecting – if we talk about harm inflicted upon artefacts by institutions, as well as violence against human bodies. All the way to the pollution of the landscape. It is a general theme of mine, leading me in various directions.

You work with historical objects that are frequently broken or damaged. In what way do these archaeological artefacts speak to you?

For me, it’s not really about archaeology, but more about how we produce stories through a constellation of broken bodies. Museums, in essence, put objects with accompanying wall tags and then contextualise them, building the timeline or story. For me, this was also a way to think about our own broken bodies, each carrying wounds, fragilities and traumas akin to the bodies of these artefacts. There is no hierarchy for me – we can also learn from these objects. I am looking at the archaeological sites or excavation sites as a form of survival, as these objects have endured for thousands of years, even in their broken and fragile states. By examining these strategies, we can also learn how to surpass the disasters and tell our own stories.

I know that you also have an interest in artefacts from black markets. What can they tell you?

When I first delved into museography-related inquiries, it was at the onset of the Syrian Revolution in 2011. During this period, a significant number of artefacts began surfacing, particularly on the black market, originating from Palmyra and various other cities in Syria. Many of these items turned out to be fake. During the war in Syria, near the border with Turkey and Lebanon, there were people in ateliers making the same gesture, sometimes using the same stones, as those employed thousands of years ago, crafting high-quality replicas. To me, this constituted, in a sense, the contemporary archaeology of the Syrian war. I think these fake objects hold even greater value as traces of a certain contemporary moment than the objects in museums like the Louvre, which are traces of a distant past. I am neither an archaeologist nor a historian – my interest lies not in the objects themselves from a purely archaeological standpoint, but in what they tell us about the current moment.

In early 2024, you held an exhibition titled Envisagement at Fondation Giacometti, creating a dialogue between the past and the present. Your sculptures interacted with the works of Alberto Giacometti, a renowned master of modern art. What significance did this exhibition hold for you?

When invited by institutions or museums, whether anthropological or archaeological, to create work in response to an existing collection, I tend to subvert this invitation. Rather than engaging in a dialogue with the collection itself, I question the act of collecting and the origins of the collection. I prefer to always have a meta reading of these museums, because this act of collecting is a tool of power. They usually produce a certain narrative at the expense of other narratives, so they choose what story to tell. It is very important to me to clarify these power structures, because museums are power structures as they shape the official discourse. As artists, I believe it is our responsibility if not to deconstruct these narratives, then at least to question them and to show a more nuanced and multifaceted history than what museums typically convey.

Do you typically get the freedom to do that?

It depends on the context. For example, I had an interesting invitation for a residency at the National Gallery in London. Typically, you are invited to create work in dialogue with a painting collection. As my usual work does not fall within this scope, I decided to explore the question of violence and examine paintings that had been vandalised inside the museum. I viewed the museum as a political site where people came and destroyed painting as a sign of protest.

Was the gallery interested in this concept?

It was exactly what they didn’t want to talk about. Their strategy is to quickly restore the artwork and exhibit it, as if the trauma never occurred. My argument is that there is something in the core of the painting that changes after being subject to violence, much like how we are altered as individuals after being subjected to violence. I aim to emphasise that the museum must take into account what happened. I am not suggesting that they leave the painting in its current state. Attempting to conceal the incident and pretending it didn't happen does not help. Eventually I managed to do this project.

Two of your main mediums, sculpture and video installation, come together in your first feature movie The Dam. It was shown in Cannes as part of The Directors’ Fortnight. Tell us what was the idea behind this movie?

The Dam is a part of my exploration into geographies of violence. During my first visit to Sudan in 2017, Ethiopia had commenced the construction of the Grand Renaissance Dam, leading to heightened tensions, particularly between Ethiopia and Egypt, regarding these resources. I found it compelling how water had become a part of geopolitical tension. I wanted to meet people who had been forcibly displaced from their lands in order to build the dam. During my scouting, I found a brickyard. As soon as I saw the workers crafting mud bricks, I realised that this is where the film should be made. It made so much sense in relation to my work and the questions that I am interested in.

How did the movie project unfold?

I spent a lot of time with the workers there and interviewed them, so the film started from the reality of the place. That is why there are no actors in this film. It’s a place that has witnessed a very violent event, which was the construction of the dam, considered one of the most destructive in the world for the ecosystem and for the local population. We start from this landscape where violence happens and try to see how this disruption then changed people’s lives and the violence against nature.

The Dam, 2022, stills, @ courtesy of Kino Elektron

The Dam was filmed during the Sudanese revolution. How do you look at this historical event in relation to the movie?

It was the end of 30 years of Islamic military dictatorship, and the beginning of the hope of certain democracy in Sudan. We began filming when there was still the dictatorship, and as the process unfolded, the regime fell. We completed The Dam after the revolution, making the film a witness to a historical moment. Unintentionally, it became the first fiction film produced after the Sudanese revolution that directly speaks about the revolution. Suddenly, this film had significance for the Sudanese people. It was fascinating to observe how creative work can respond to the historical events, remain relevant, and feed in from reality to fiction and fiction into reality.

A monument in the movie, constructed by the main character Maher, is made of mud. It is a primary material that you frequently work with. What is the reason for choosing it?

Mud is the beginning of everything in all the cultures. From mud we build our mythology. We made the first pottery, the first houses from mud. It’s also the first artistic gesture of making small statues and objects. As an artist, I thought that going back to this origin is a way also to investigate the power of this very simple coming together of earth and water.

You have an exhibition scheduled at the Vienna Secession at the end of 2024. Could you elaborate on the project you are working on?

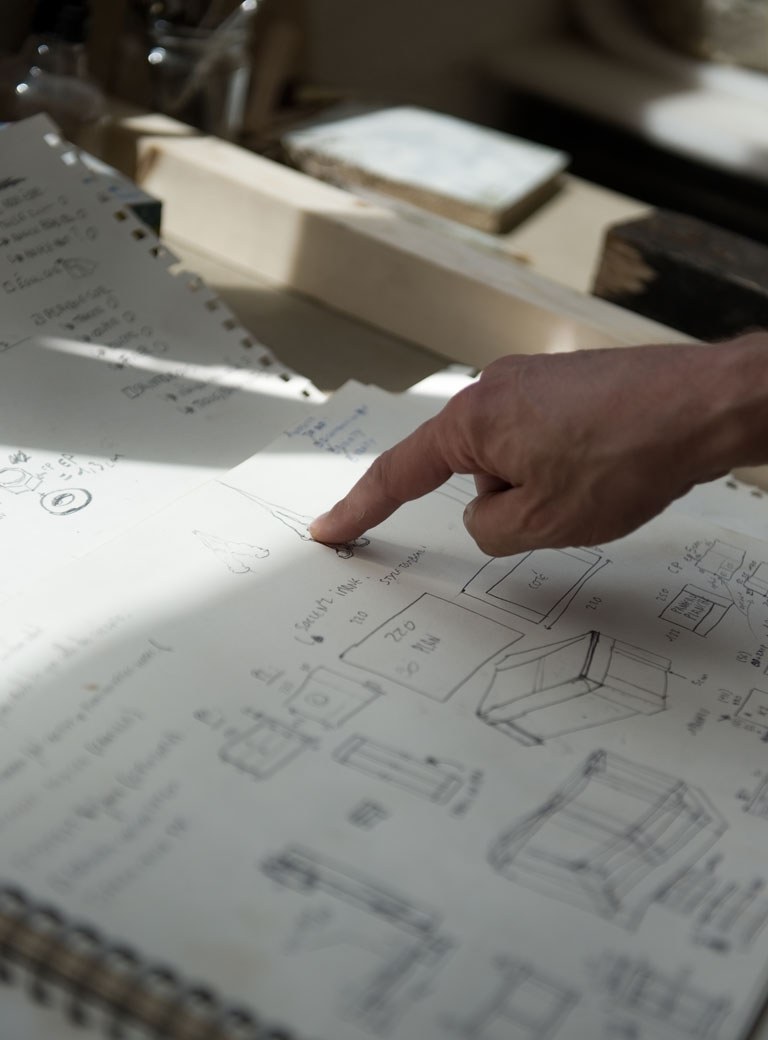

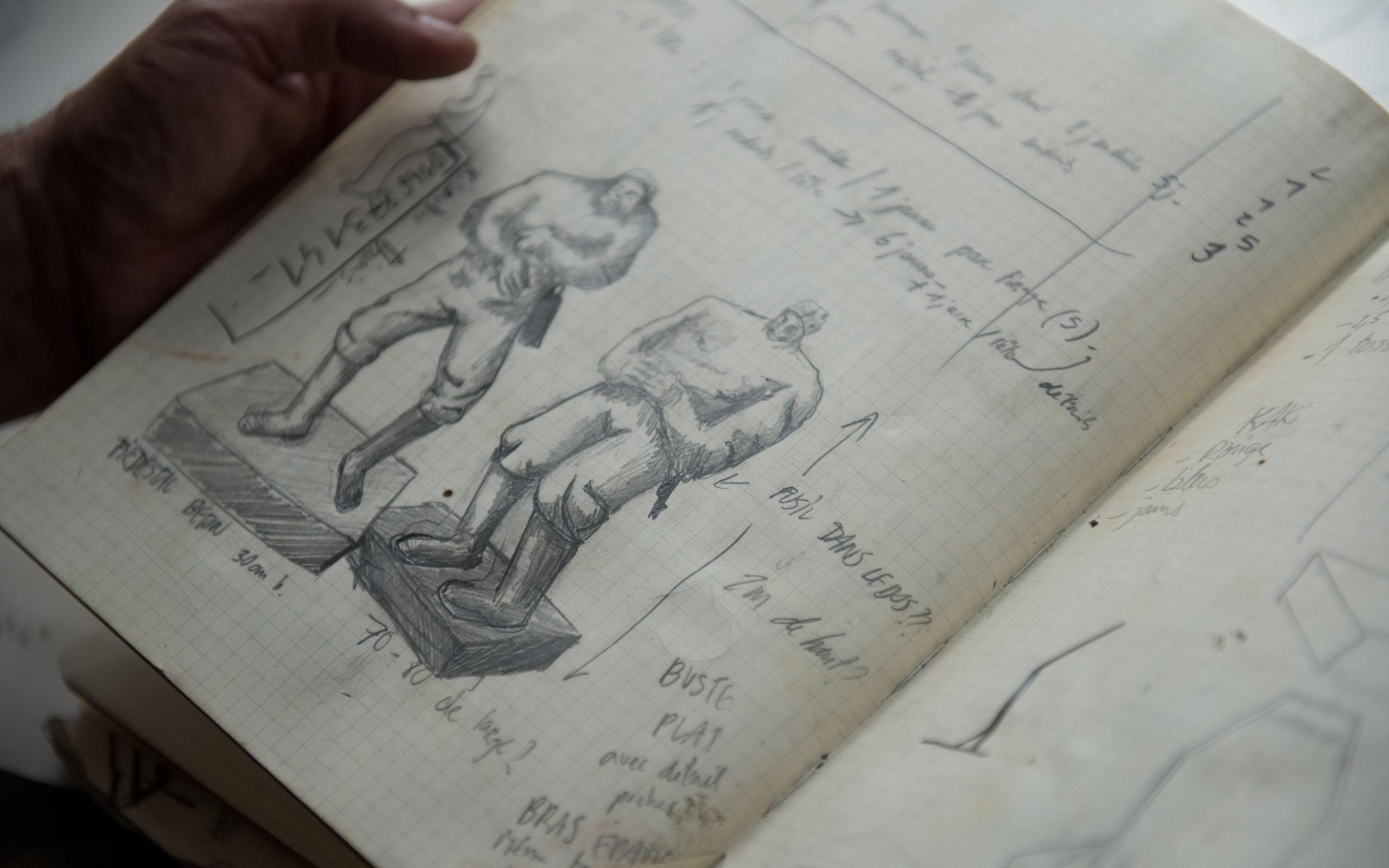

My new sculptures will be a new mixture of materials: mud and bronze. I’m trying to look at these materials with the imaginaries around this materiality. Bronze is typically used for statues depicting heroes seen on the streets, representing the official narrative of historical figures. These statues are enduring symbols made from bronze, a material known for its longevity. I consider the monuments as apparatus of dominance of power. These are the tools that are used by the powerful people to create their regime and sometimes oppression. In my work, I try to dismantle these tools of power of dominance.

What does mud represent?

Mud symbolises fragility, representing the oppressed people who lack power. There is a power dynamic between bronze and mud, reflecting the tension between two regimes of power – the power from above and the power from below. I’m interested in this idea of rot, how the humidity of mud could infiltrate the bronze and start making it fragile and defected. This process symbolises a reclaiming of power through putrefaction.

Does any material have a political meaning for you?

It’s always political for me. You can’t talk about water, for instance, in an abstract way. Water is either life and something that people look for. Or it is delusion, devastation and dams. Everything exists in a socio-political context.

Aside from sculptures, what else are you going to feature in the exhibition?

I’ll also be showing the three channel video installation Of Men and Gods and Mud and a new series of drawings. I’m creating a sort of museographic vitrine with different pedestals of monuments. I’m researching monuments that were destroyed in different places starting from after the Arab Spring in Egypt, Libya, Yemen and Syria, but also in Eastern Europe and post-Soviet countries – all the leftovers of pedestals that have lost their monuments.

Exhibition view, Envisagement, 2024, Institut Giacometti, Paris © Succession Alberto Giacometti-ADAGP, Paris

Alberto Giacometti, Standing Woman c. 1961, left; The Tall Lady, right, 2022, exhibition view Envisagement, Institut Giacometti Paris, Succession Alberto Giacometti ADAGP, Paris

Exhibition view, If you prick us, do we not bleed?, The National Gallery, London © The National Gallery, London

Interview: Anton Isiukov

Photos: Elise Toïdé