Andrea Grützner belongs to a group of young, aspiring photographers in Germany who received international recognition not long after completion of their studies. Her photographs are presented in the form of concentrated image sections with picturesque, abstract, and seemingly surreal fragments in bright colors. In her Berlin studio she speaks with us about her first series Erbgericht, the photographic significance of memory in the medium of photography and her emotional sense of home in terms of her mother’s beef broth with mashed potatoes.

Andrea, how did photography come to you? Or how did you come to photography?

My first real reflection of photography occurred on an “open day” sometime in the 1990s in a mathematical institute, where my father worked. He used an early version of Photoshop, which allowed to have one’s own face transformed into a facsimile of a stone relief and to be able to take it with you as a print. It was a real crowd puller, especially for us children. A first digital version of children’s face painting! Subsequently, I’ve often played with the program and finally understood that even while photographing one can also play a lot.

The exhibition series “gute aussichten – junge deutsche fotografie” (“good prospects – young German photography”) presented a major opportunity for young photographic talents to gain visibility right after the completion of their studies. In 2014/2015 you were one of the award winners with Erbgericht. Has this inspired your development since then?

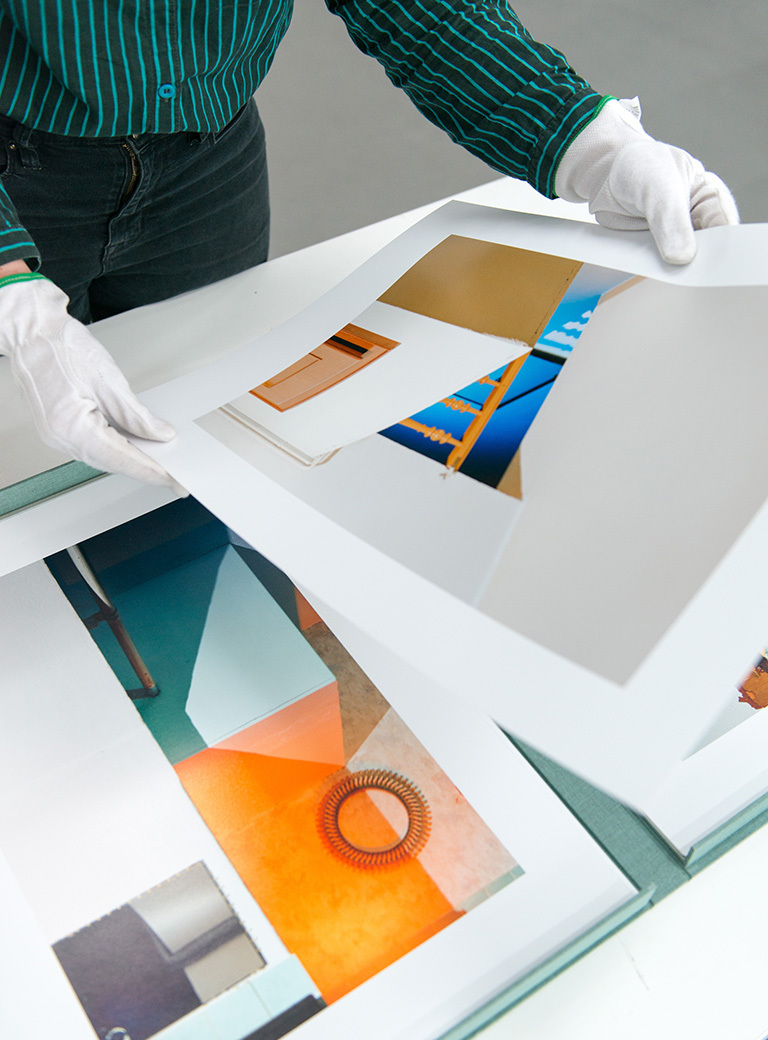

The exhibitions “good prospects” was held in renowned museums, including the Deichtorhallen in Hamburg and the MARTa Herford, was visited by many people who organize exhibition spaces or otherwise work in the broad field of photography and art. The last two years have resulted in great solo exhibitions for me, for example at Kunstverein Lüneburg, at the project space Walzwerk Null in Düsseldorf, at Galerie Coucou in Kassel and, most recently, at Galerie Rundgaenger in Frankfurt. It is wonderful to realize that people trust your work. During the various different “good prospects” exhibitions, I found it very valuable to get to know the different institutions, their people and way of working, and to experience such a degree of professionalism so shortly after the completion of my studies, something which would otherwise have taken much longer: Things such as attending to insurance needs, work lists, the construction of robust equipment transportation cases, the organization of successful presentations, the making of contacts, and the ability to speak and write about one’s work. All of that together with networking, particularly with former award winners, provides an enriching experience that makes many things easier.

With so many photographic talents passing from the art academies each year it must be hard to gain acceptance and to stand out?

How does one find one’s own style? My work Erbgericht developed from my obsession at the time with this one building for which I was trying to find an appropriate visual dialog. It meant an intensive long involvement with theory, history, other artworks, images, my professors Katharina Bosse and Dr. Kirsten Wagner, local residents, my co-students. As for the photographic processes, there was a lot of “trial and error” and my experimentation sometimes resulted in going off on the wrong track. I am sure that my first study in communication design in Konstanz contributed to the sharpening of my graphic eye. I am in the process of exploring various terms and concepts of abstraction, from which, I expect, very different stylistic and aesthetic works can develop.

Your work is located at the interface of photography, collage, and graphics. However, your main medium is photography. Why does photography exert such a force of attraction on you?

The camera documents with light that exists. Both the photographic object and its shadow are an index, referencing a spatial and temporal relationship. I can use the camera as a magic wand: The world, the message, and the content change through minute movements. A short or an extended exposure alters the sense of continuous time, with a wider aperture or other focal length I can include things, or conversely, I can exclude things. Photography is a complex field of possibilities with fundamental documentary properties. It is a medium with which one can document, manipulate, irritate, flatter, admire, and play. And time and again it is being used to touch the invisible and make it visible.

For your series “Erbgericht” and “Tanztee” you returned to your old home. What is home for you and where are you most likely to find it at this time?

Home is where family and friends are. Home represents encounters and certain moments that remind one of something. Home for me is mom’s beef broth with mashed potatoes, my grandma’s bread rolls with jam, and also falafel with my friend in Berlin. There is also another kind of visual home or home of things, which for me are among other things, tiled facades in the Palatinate region and GDR roughcast, Saxon Switzerland, and the Palatine Forest. The inn “Erbgericht” in the Saxon Polenz, too, inspires a feeling of home and is the place where we have celebrated family feasts for as long as I can remember. Home is a construction and a conflation of memories with the present, a special, familiar feeling of momentary well-being, often combined with both sentimentality and alienation.

Your photographs show places filled with memories. Are these always your own memories, or collective recollections of places and times gone by?

The people of Polenz have told me that “everything has happened” in their Erbgericht. The inn is a historically grown material and space collage and it has been managed by one family for five generations through five political systems. Depending on the situation at the time, it was added to or partially rebuilt. In the conversations the interior was interwoven with stories. However, the memories remain only partly imaginable for me, they color the walls abstractly. Spaces do not ‘tell’ by themselves, it is our projections onto them that do that. The house is a cultural anchor point, with numerous secrets. In the dialog I notice that things appear familiar to me, yet many things remain alien to me. I have integrated these feelings as well as the memory of my childhood experiences in this house into my work processes. I trace the indeterminable magic with my colorful light that inscribes itself into the analog slide-film material, opening ‘other spaces’ with the images. It’s a balancing act between likeness and abstraction, the familiar and the unfamiliar, orientation and dissolution. I find it very exciting that through the bright colorful shadows that actually mantle and disguise the architecture for the instant of a moment the real time of the place seems to dissolve. The result is fragmentary, like memory and a new inchoate as yet unformed construction.

In the context of the scholarship “Koblenzer Stadtfotografen” (“Koblenz city photographers”) from which the series “das Eck” (the corner) and the book by the same title, published by Kerber Publishers, have emerged, you have again created a portrait of a place, in this case, the city of Koblenz; how did you approach this city portrait? How did you approach the town?

During my first visit to Koblenz, one of Germany’s oldest cities, I noticed that the old and the new mix in an unusual way. The city was largely destroyed during the Second World War and afterwards, many scarred bomb sites were built upon utilizing the typical postwar architecture of the region, yet the view of the city is not entirely determined by this. The ancient Roman, Prussian aspects and the romanticism of the Rhine are also stressed for touristic purposes. I walked through many parts of the city center and intuitively documented what I found interesting. I pasted the pictures in several sketchbooks and I returned to many locations to take further photos with an analog camera. It is a challenge to involve oneself in the limited time frame of a few months 'artistically' in an unknown city. Only in time does one get to know people and become able to make an interchange with them about their environment. If I were to return to Koblenz now, a completely new work would develop.

Your concentrated picture sections show picturesque, abstract fragments, for the most part in bright colors. Yet they have as in the case of “das Eck” little to do with cityscapes as we usually perceive them. What do these pictures transport in your perception?

In Koblenz I noticed many, slightly surreal things which made me smile; it could be unlikely combinations of materials, a peculiar wall painting, or a strange entrance way. Photographing them, I separated them from their environment. From my personal perspective, some strange things developed precisely from this separation. Having decided to focus my attention on details of the postwar architecture that now characterizes the city view, I further added contrasting details of older buildings. With their black background they appear like museum artifacts, losing their scale and reference. For me they represent symbolically the museum- like image that Koblenz presents for purposes of tourism. These were the ideas that have led to these pictures. What viewers see or want to see in the end, what they are thinking of, is pure speculation and fortunately an open process with many possibilities. Of course, I have my own thoughts and emotions regarding individual pictures, but I do not want these to be so easily accessible.

In your photographs, there are no people to be seen; are you afraid of too much directness?

The great challenge with portraits is balance or the precise definition between directness and appropriate distance, individuality and universality, personality of the portrayed person and image form. A human being has so many facets, and the photograph is therefore always both a reduction and a concentration. When is a portrait authentic? I do take photographs privately, I like people in pictures and am still searching for my artistic approach to portraits. In my old homeland it was a careful, curious quest groping for the environment of my family, the society around them. I like to talk to people, actually a lot, but for me it was more appropriate to first approach the topic through spaces made by people. In the process the house became my muse. People are in my works, with their traces, their actions, their products. And at the same time their places change into something new in the picture.

You seem to apply light and shadow very precisely, for example in order to draw sharp edges which enhances the constructivist character. How important is the play of light and shadows in your pictures?

Without light and shadow our entire visual world would neither be imaginable, nor representable. There would also be no history of photography. Time and again I notice wonderful light situations which captivate me and which carry a kind of sublimity. Unfortunately I hardly ever manage to capture this light feeling. It makes me very happy to discover photographs with this light regardless of who photographed them. I can’t describe this light with words only. The most beautiful in the inn Erbgericht for example was the late summer evening sun falling through the old windows into the cloakroom and casting streaks of light across the floor. Yet there is the danger that this light effect can evoke nostalgia, sentimentality, and therefore result in stereotypical images.

Do you have idols or “heroes”, that is, people from the field of photography or elsewhere who you admire or who inspire you?

My thoughts are inspired through many different things. It would feel strange to me to name someone directly. If I have questions, I find answers in my works, in various approaches and in conversation.

Which are the exciting things in your program this year?

First I will participate at the Photo London in May. And in June I’ll have an exhibition at the Center for Contemporary Photography Melbourne, Australia. I’ll be on the road a lot this year.

Interview: Julia Rosenbaum

Photos: Michael Danner