He photographs powerful women, reflects on German myths in his works, and deals with the relationship between man and nature. Andreas Mühe is one of Germany’s most renowned (photo) artists. In his ambiguous works he deals with sociological, historical, and political themes, which he elaborately stages with light contrasts in special environments. His work is marked by the ruptures of German history, photographic experiments, and his socialization in the former GDR.

Andreas, were art and photography already important to you in your childhood and youth?

Here I must distinguish between these three phases: As a child, my brother and I were simply taken to museums and exhibitions without being able to decide whether we wanted to see them or not. A few years later, we wanted to escape these permanent activities by trying to be allowed to stay at home, outside, or with friends. A big change came in the 1990s when we visited the Ludwig Collection in Cologne with our father. The American pop culture exhibited there, especially the works of Robert Rauschenberg, Roy Lichtenstein, and Keith Haring opened a new horizon for me. The preference for contemporary art and for the disruption of visual habits comfortable to me has remained. In the theater, I preferred the narrative for a long time; the Deutsches Theater in Berlin was closer to me than the Volksbühne in the early days of Frank Castorf. During my apprenticeship, I received my first photographic equipment from my parents. Two assistantships, first with Ali Kepenek and then with Anatol Kotte, have shaped me.

How did you get started in photography?

I completed a fourteen-day professional internship during my school years at PPS in Berlin, a photo lab founded by F. C. Gundlach in 1971 in Hamburg, which opened a branch in East Berlin in the 1990s. The management in Berlin was in the hands of Robert Jarmatz, who later founded Pixelgrain, there was also a photo lab where I completed an apprenticeship and with whom I still work today. PPS worked for professional photographers and also exhibited in the business premises in keeping with the spirit of its founder, F. C. Gundlach, who was a photographer as well as a collector and an inspirer.

How do you develop your themes or how do themes come to you?

In my beginner years I photographed people for magazines, that is, in the form of commissioned work for newspapers and magazines. The subjects came to me via requests whose content other people had come up with. Then there was an intermediate phase where, because of the way I was already in the process of developing my own style, I was approached for portraits that gave me a say in the choice of location and perspective, or even wanted my choice. It was through these intermediate steps that I began to tackle my own subjects. The fact of coming from the East and looking to the West already determined my choice of subjects. At the beginning, I dealt with Friedrich Engels study The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State from almost 150 years ago. I still consider the family to be the nucleus of the state and society, although I believe it is in the process of dissolution, and I understand the consequences of National Socialism in Germany since its division and reunification as a hitherto unhealed gaping wound of the Cold War. The existence of the Iron Curtain between East and West made us spectators of the world stage, who quite senselessly tried to perform our own play.

There are still many topics on the dump of German history.

What was the first formative exhibition for you?

Here I return once again to Cologne Cathedral and Museum Ludwig. The proximity of Pop Art and everyday culture fascinated me. The discovery of the West via a gleaning of contemporary American art of the second half of the 20th century was my access for first own works. The young, sometimes purely temporary fashion labels, the band from my circle of friends needing a cover and a wacky location for their presentation; there one collaborated, designed, discarded, designed. Friendships were used in many ways, and the hustle and bustle of everyday life and the new everyday culture of a city that was reinventing itself at lightning speed determined life and work. In the early 1990s, we lived for a short time in Hamburg. A city that was still setting the tone at the time, and then we noticed how Berlin was catching up. Maybe I’m just saying that it was less the exhibitions and more the turbulent times that shaped me.

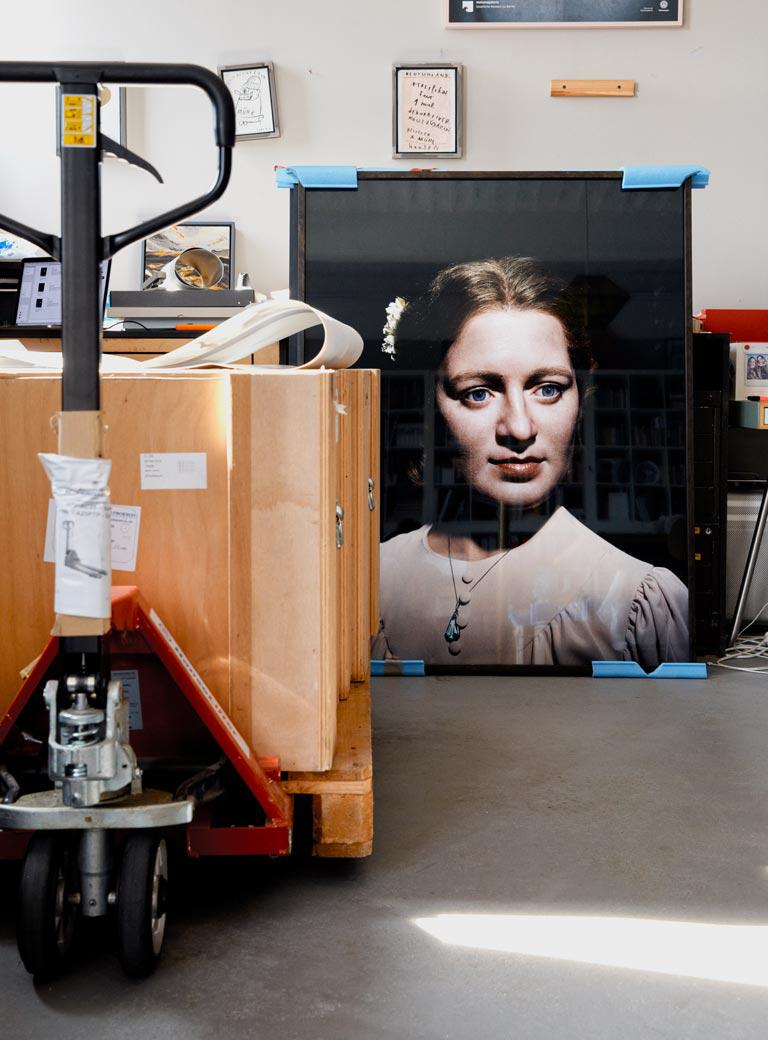

RAFNSU, 2023, Credit: Andreas Mühe, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2023

In many of your works, such as Obersalzberg, national myths and the dark side of German history play a role. How do you approach such topics?

From early youth I felt at home on snowboards, skateboards, surfboards, and skis. Winter sports brought me to the Berchtesgaden area. The beauty of the landscape around the Watzmann impressed me with a degree of sublimity that having inspired Caspar David Friedrich in the past, had more recently been occupied and sullied by the National Socialists. Of course, Friedrich’s paintings had “a reflected view into history and its transformation for the present viewer,” as Stefan Trinks put it in his review of the exhibition in Schweinfurt: Caspar David Friedrich and the Harbingers of Romanticism. In the search for European beaches suitable for surfing, one does not find the breaking waves of the Atlantic Ocean alone, for in the middle of the Atlantic Wall to this day there remains an extensive system of wartime defenses and fortifications. No matter whether you surf in Klitmøller or Cap Ferret, German history is present everywhere. Surfing and visiting bunkers became an obsession for me and this was reflected in a project yet to be exhibited.

Your motifs are perfectly staged and yet, in the end, what is seen at first glance is not what is seen at all. I’m thinking of your series A. M. – Eine Deutschlandreise with your mother as Merkel’s double. How did the idea for that come about?

In the past I have photographed politicians. The shots of Mrs. Merkel gave me the stamp “Chancellor photographer.” I had studied National Socialist image politics and Heinrich Hoffmann, had analyzed and re-enacted the poses that his political celebrities assume, in other words, apparently doubled. How do I manage to become a double myself, in order to question my work in this way? That was the task I set myself.

Then how did you implement it?

I sent a fictitious chancellor in a real car, but one that was too cramped for the shots, through Germany to look out of the car at German circumstances at exemplary places (important to me, significant for German history and/or for mythmaking). At Zugspitze, miraculously, she looks out of the car and gets out. She looks at the original filming location of Heimat by Edgar Reitz, the fictitious Schabbach, the forge of the Henninger family in Gehlweiler in the Hunsrück, and in turn to Golzow, venue of a long-term filmic study Die Kinder von Golzow (The Children of Golzow) by Barbara and Winfried Junge, double Heimat: West and East, to pick only two examples. But Chemnitz, my birthplace, and Stammheim, home of the Stuttgart prison, also appear here. On August 27, 2013, a short time after completion, the series will be presented for a few days in the old girls’ school in Berlin-Mitte. At the opening of the exhibition, the press office of the Federal Chancellery has to deny the Chancellor’s involvement in the series. Everyone assumes that I was allowed to accompany the acting chancellor on a tour. Mission accomplished.

What does a typical day in the studio look like for you?

Untypical. I’m shocked at how rare it has become for me to press the shutter.

Is photography a medium against transience?

Yes, if you manage to capture the “face of time”. August Sander gave this title to a collection of 60 photographs from the first third of the 20th century. In the preface, Von Gesichtern, Bildern und ihrer Wahrheit, (Of Faces, Pictures, and Their Truth) Alfred Döblin describes how the legibility of social change through the violence of human society was inscribed in the portraits. In the “equalization, the blurring of personal and private differences, the receding of such differences” he sees the universality, the universal of these portraits.

You once said in an interview that photography is something like sculpture for you. What do you mean by that?

Now and then light plays the main role in my preparation. The use of artificial light, even in outdoor shots, enhances the place, time, and sometimes the action or the motionlessness. In sculpture, light, shadow, and reflection of the material are equally essential components for the effect.

The theme of “power” is also a very crucial, it characterizes your Desk series.

What can a room tell in its absence about the person who worked, lived, had conversations, maybe even partied here? Desks are places for decisions, where judgments are made, deferrals are granted, laws are created or voided. They are the apartments of power. If their occupants are present, they quickly become their own actors. The empty desk symbolizes power. The powerful person at the desk quickly mutates into a staged photograph of a child, such as with the “Schultüte” on the day of enrollment in school or even much earlier with a photographer in the studio, where one could choose the background and the interior in the foreground. Spending three days in chancellor Ludwig Erhard’s bungalow in Bonn, which vividly illustrates his vision of the future of the Federal Republic in its clear architecture and basic modern furnishings, was a balancing act between the vision of the builder and the right of its changing occupants to comfort and perhaps a bit of silk wallpaper. For me, an example of how power shrinks in the face of bathroom tiles and a kitchenette.

What role does the connection between man and nature play in your work?

The walk in the countryside is already in Hölderlin’s call “Come!Into!the!Open!Friend!” interspersed with the “leaden time”. I cannot imagine that there ever was a unity of man and nature (except in paradise). We live in the Anthropocene era and are gambling away our responsibility for the future of our planet. The observer of this breathtaking beauty of nature, which makes us kneel, linger, and be silent, is being watched and is under control. What he thinks or feels never reflects nature, but it pushes him to his suffering, guilt, and transience. I avoid the picturesque debris field of an artificial ruin; man in the landscape is enough for me: between abuse (pissing Nazis at Obersalzberg), rest on the run, and the transformation of man’s nature into biorobots to “clean up” nuclear waste. In my own despair I have also already put myself ostentatiously and nakedly near the chalk rock on Rügen, a landscape that belongs to Caspar David Friedrich.

How does growing up in the former GDR shape your work?

I was born in Karl-Marx-Stadt in the former GDR. The country no longer exists and there is no longer a city with that name. However, the city of Chemnitz still exists. Should we conclude from this that the country also still exists? In my mother’s birthplace in the Uckermark, the tiniest street in the village, which has a kink in it, was named after Karl Marx. Now it's called “Stiller Winkel”. Dirk Oschmann hit the nail on the head with his recently published book The East: A West German Invention. With the founding of two German states and the onset of the Cold War, the West is practicing non-recognition of the East. From its point of view, the East does not exist. The East remains no man's land even after the temporary end of the Cold War. I grew up in the niche culture of the East: when the GDR closed itself off absolutely and barricaded itself in, its citizens consciously chose the niche, which was open-heartedly celebrated and tolerated. This was lived dialectics, that is, the negation of negation. I still hope that something of this way of thinking has remained with me.

Kanzlerbungalow, 2021, Credit: Andreas Mühe, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2023

Kanzlerbungalow, 2021, Credit: Andreas Mühe, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2023

What topics and projects are moving you at the moment?

I am currently working heavily on The Bunkers from the Atlantic Wall Move Toward Me – a larger work that can still wait for the right exhibition space. Die Wismut is another current work. In 2025, Chemnitz will be the Capital of Culture. Wismut is a heavy legacy for the city and the region. As early as the end of WWII, Soviet geologists were on the move in German territory, searching for possible mineable mineral resources. Uranium was found in the old mining tunnels in the region around Chemnitz. For decades, uranium was mined here for Soviet production of nuclear weapons and used to make plutonium in nuclear reactors. Bismuth is a chemical element, and the name was used to camouflage and downplay uranium mining. The Chernobyl biorobots, people who tried to contain the nuclear disaster after the reactor accident, died from bismuth uranium. The miners of Wismut also became ill. Wismut as a company worked like a separate state within the state of the former GDR. Nevertheless, there was a great identification of the people in the Ore Mountains with their activity. Since 1991, the federal company Wismut GmbH has been in charge of cleaning up the radioactively contaminated Wismut waste sites.

In May 2023, your exhibition Brothers and Sisters opened in Frankfurt am Main, on the occasion of the 175th anniversary of the Paulskirche Assembly. What story did you tell in this show?

I go back into the past of my mother’s side of the family to the end of WWII and the murder of my great-grandparents in April 1945 and couple this murder with their murderers. On the basis of two terrorist groups, the RAF and the NSU, the question of a specifically German form of terrorism arises. Are they political persuaders and/or murderers because of the German National Socialist past. What can and must democracy endure?

Exhibition Stories of Conflict, Städel Museum, 2022, Photo: Norbert Miguletz

Exhibition Stories of Conflict, Städel Museum, 2022, Photo: Norbert Miguletz

Is your art always also political?

I’m interested in looking at both sides of a coin and, if possible, finding a way to put these two sides of a coin into one image. Subversive practices are a way for me to put more information and irritants into a picture than is normally possible. Sometimes I build conundrums that are not immediately decipherable. That something is so or seems so, as it cannot actually be possible, it is sometimes in the detail or in the arrangement itself. The use of light can also support this. Supposedly, one learns subversion in dictatorships, that is, from politics. In that sense, what I do is political.

Interview: Kevin Hanschke

Photos: Patrick Desbrosses