Landscape is a central motif in the work and constructions of graphic artist Andreas Werner, who was born in the former GDR and grew up in Lower Austria. With influences from the 19th century conjoining with science fiction, he experiments with romantic ideals and utopian conceptions transferring landscapes into our present time. In the universes he creates, he explores the question of what has become of utopian ideals and whether the idea of future was once more optimistic.

Andreas, you first studied theater, film, and media science and then moved on to art. How did these changes come about?

I have always made art, but after having studied in these other areas, I am now making art seriously; this progression however, took some time. I decided to study theater, film and media science because I am interested in those fields, and during my studies I realized that I actually didn’t want to lecture so much about the art of other artists, but that it would be more exciting to produce art myself. At first I attended the University of Applied Arts, but then I changed to the Academy of Fine Arts to study with Gunter Damisch and I graduated there in 2012.

Why did you choose graphic art?

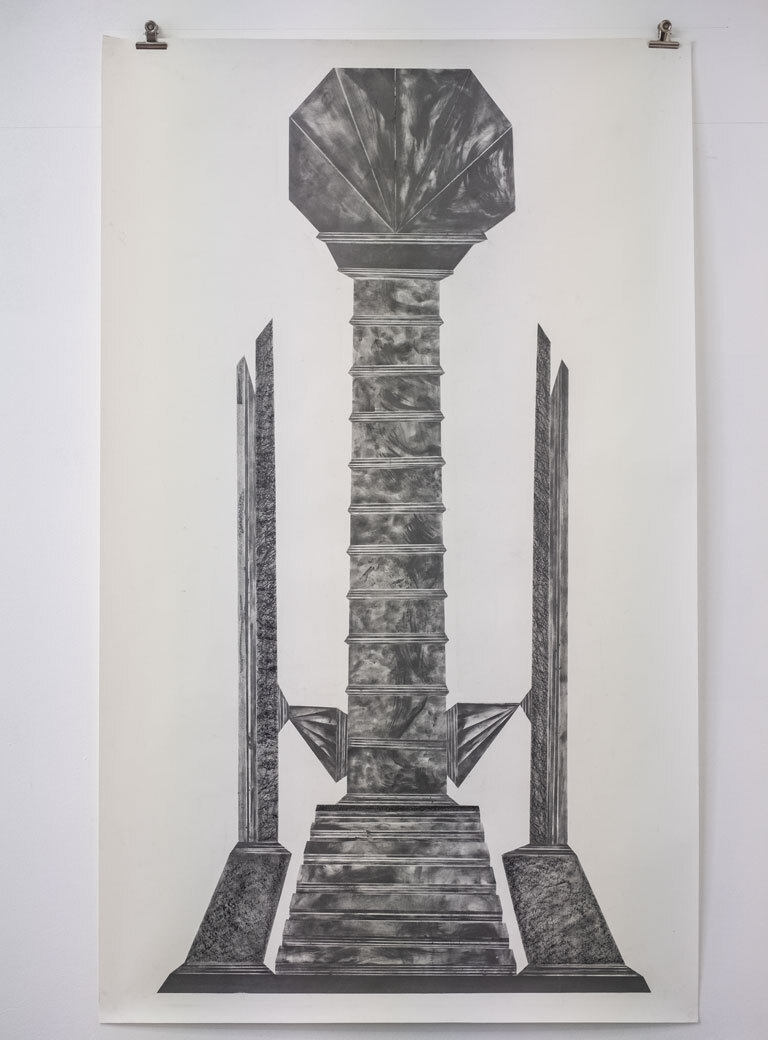

That was not really a deliberate decision, since I have always been more of a draftsman. I liked the idea of creating something just with thoughts, that is, just taking a piece of paper and a pencil, material that is easily available, creating something special out of almost nothing. And so I delved further into pencil drawing in order to achieve an aesthetic or a possibility that I feel has something very special.

Has paper always been your preferred material?

Working with paper has a certain freedom for me, because it is simply a piece of paper and if a drawing doesn’t work out, it doesn’t matter, because then I just take another piece of paper and continue to work. This way of working has certainly changed for me over the years, because now I use a much higher-quality paper. But this lightness of paper has remained appealing to me because it has a coolness that canvas can never achieve.

You have one studio in Vienna and another one in Lower Austria. How does your day-to-day work differ here?

In Vienna, I work mainly with small formats and use the studio partly as a warehouse and showroom. In Lower Austria, out in the country, the space is bigger and brighter, and I have a garden. I am not the kind of person who works directly; I plan my work very carefully. Then I start and tell myself that the works need to hang a little while and I must think a little bit: does the work need something, or is it sufficient as it is. It is such a fine line between now it is right and now it is too much. And it is super nice to be able to take a walk in the garden or just sit under a tree and pause for a while and then go back to the studio. That is what I enjoy about the country studio. For me it is the perfect balance to the work in the studio, which is very structured and very concentrated. When I’m at work, I don’t listen to music, but am almost completely meditative with my pencil and work in a concentrated way, in complete isolation and quiet. That can be very exhausting, and then it is refreshing to go out into the garden and take care of my vegetable patch.

How would you describe your creative work process?

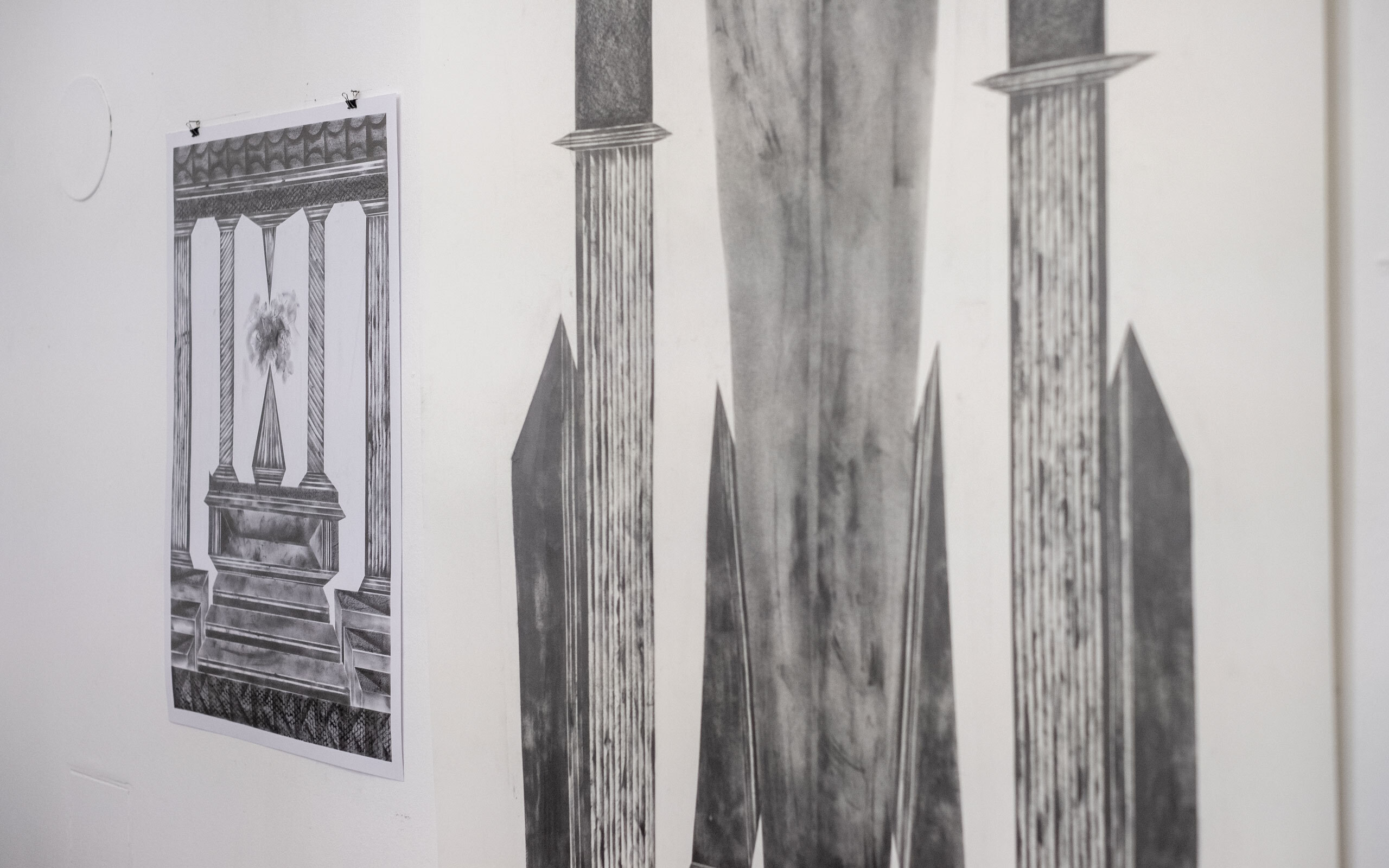

I always work in series; I never perceive a work as just one work, there is always a sequence of works. I usually carry some pieces of paper or a sketchbook along. In the last few years, I have been fortunate enough to be invited to artist residencies in Ireland, Hungary, and Croatia. I have a passion for science fiction and archaeology. If I find some old stones or information about ancient cultures, I get excited and read up on it, do research and make sketches pertaining to it, and all of these sketches I later work with in the studio. I found this detail of a temple quite interesting and used it. Or I notice things in literature, like Stanisław Lem’s descriptions of buildings, cultures, and planets, and I combine these elements like collages and draw them. My works emerge from roaming through all kinds of media, different eras, and places.

In general, you move between realism and abstraction. Has your work changed over the years?

It is more of a rotation. There are these realistic moments, and then there are moments where I move into the more abstract or the freer. This is all interdependent. For me it’s a horror to repeat myself by painting the same picture, and it’s boring for my development, because it predetermines what comes next. I make exact sketches and have my conceptions, but the creative process is almost like jazz music, one has an idea of how it works, but then I seek this freedom and let myself drift and the most exciting things result.

Landscape is one of your central motifs. You once described yourself as a romantic of the new millennium…

That’s right. (laughs) Romantic landscape painting fascinates me. Looking at the paintings by William Turner or Caspar David Friedrich, they are about creating depth and atmosphere with color. During a residency in northern Germany I visited Kunsthalle Hamburg and saw Caspar David Friedrich’s painting The Sea of Ice and was fascinated, seeing this ship that is bursting, sinking, and when you look closer you see the ship’s name “Hope.” It can’t get more romantic than that; it is hope that is sinking there! Having seen this painting, I began occupying myself with landscape. What does landscape mean today? Is it still this romantic picture that we have in mind and did it ever exist? Even at the beginning of Romanticism … we were already in the middle of the industrial revolution. So the landscapes they were presenting to us no longer existed – it was escapism in the broadest sense. I began to pursue escapism in art, and over the years I compared these landscapes with other planets and their landscapes, because I am fascinated by science fiction and I asked myself: what is happening in these landscapes? And in the process I came up with these monuments, spaceships, and robotic figures that are never presented independently, as it were. What I create are universes.

You were born in the former GDR and grew up in Lower Austria. Has this past influenced you?

I come from Merseburg, the industrial area without parallel. I can remember that the landscape was covered with coal dust. My impressions of the architecture of that time as I persistently cite in my work today is partly about Brutalism, partly about prefabricated buildings. That is the origin of the aesthetic I work and play with on the one hand, and on the other it derives from film sets like Metropolis and Blade Runner. I play with these ideas people have about it. But basically I would say that over the years my aesthetic has developed in such a way that I fall back on my earliest childhood memories, for example visiting Berlin for the first time in the 1980s and I am standing in this gray Berlin in front of these huge monumental buildings on Karl-Marx-Allee. These sights were very formative and are biographical in that respect.

Caspar David Friedrich is a source of inspiration for you. Are there other 19th century or contemporary references that move you?

Yes, there is an insanely wide range. I love Caspar David Friedrich and William Turner. But I also like a lot of contemporary artists like Karla Black, and Sarah Morris, who has such a minimalist approach. I consider Per Kirkeby one of the best painters ever with his layering, which is more about geology, but should I name more? Perhaps not… (laughs) I have a more playful approach, I find things exciting that carry me along. When I go to an exhibition, something has to happen inside me; it can be video art, it can be performance or an installation. Carol Bove, and also the artist group Laibach, are super. I draw as much from art history as I do from popular culture, but in the working process one should free oneself from that.

Does that mean you react more to the work and less to the artist?

I do react more to the work. This discussion about artist and work and whether you have to separate them, yes, I think you have to separate them. One has nothing to do with the other. There are certainly things done by some people that are not okay and I would say that is now indisputable, without question. In this respect, I am less interested in the work than the person, if I’m honest.

Where would you place your art in the present?

I think my work is difficult to classify in terms of time, it’s both romantic and utopian, although Romanticism underlies the entire thing. I certainly have views on world improvement, but for me it’s about developing my own aesthetic and formal language. In a best case scenario this means that the work attains something approximating a unique selling point, it attains authenticity, as it were, which I find exhilarating and gratifying. But generally speaking, can art still be classified today? Perhaps to some extent fifty years subsequent to its engenderment, and then it’s still inaccurate; but then, that’s what we have art historians for.

In the utopias or landscapes that you create, man is absent, but we find traces…

Exactly. We find traces and vestiges of people and civilizations; it’s not even clear if they are of people. The landscape is a construction. Landscape painting, both illusionist and romantic, has always been a construction or a kind of science fiction view of how we would like it to be, it has never actually derived from reality. Especially today, landscape untouched by man no longer exists in Central Europe. Landscape is subjected to exploitation and industrialization. Man strives to subordinate the planet, in the biblical sense as it were, but gradually people realize that it isn’t working, and if we continue in this way, we will go beyond the point of the irremediable. If we are truly concerned, in what direction do we truly want to develop? And furthermore, what do landscape and nature mean to us on this planet?

Is there a claim for you as an artist or are there actions that you want to evoke?

Basically, yes, for myself I have a claim, but I do not demand its acceptance by the viewer. I try to organize my thoughts and formulate a utopia, an idea. Whether you are in agreement or see it differently is up to you. As an artist, I don’t have to explain myself, those who want to accept it do so, and those who don’t want to just don’t, and that’s perfectly legitimate, because everyone comes with their own biography, with their own history. Of course, not everyone will see the GDR past, but rather Greek temples and I would never say that’s not the case, but rather that’s cool, tell me more about it. The playful element is important to me. Pictures in the classical sense need quiet and contemplation. I have to be able to engage with them, because the medium works through silence, time, and in the best circumstance, discourse.

So you are offering levels of meaning?

Exactly. I consider that an opportunity for artists. I don’t think you can give any answers as an artist, and I don’t think it’s the function of art, for that there are scientists and philosophers. As an artist, I see myself more as offering levels of meaning and formulating insights. Furthermore, I believe that art precedes science. Let’s go back to science fiction like the Enterprise. Set designers and artists have always formulated a reality in advance of its actuality, like the flat for example, which was then realized because a lot of these scientists are nerds and into these series, saying: great, I want something like that, how could I build it, how can it work?

Do you wish that the utopias that you create could give rise to a new reality?

That would be asking too much. (laughs) Well, it would be cool, but I don’t have that wish. But it would be great if such robotic creatures could be around.

Are there any prejudices or misconceptions about your work?

My aesthetic is deliberately unclassifiable at first glance, but I do demand something of the viewer. When I cite Brutalism or monumental buildings like the “Seven Heaviest” in Moscow, there is certainly something very charged about it, but nevertheless I am playing with it. It’s a play with aesthetics and derives much more from Expressionist film and science fiction. I would rather locate myself there. I play, as it were, with pathos in a very reflective way, and pathos that is not deliberate is bullshit nonpareil, but when you take pathos for a ride, it’s more to have fun with it, and not for it to be taken completely seriously.

In one artist’s statement, you ask what happened to all the utopias and why is the idea of the future so unkind?

In my childhood, science fiction or ideas of the future had something of a new beginning or beauty, because humanity would have conquered all problems and we would live together in peace, and that’s a beautiful idea. But the peace and love movement that underlaid hippie culture, which then found expression in science fiction, as it were, has been lost over time. When I look at science fiction today, it is really just dystopias. What happened? And one of the essential things, especially because of my GDR past, I think: With the collapse of the Soviet Union and of real existing socialism, the last utopia in this form unfortunately perished. Regardless of how it was realized, there was an idea of humanity and a better life for all but it failed and what is left is the capitalist system, which is basically not a utopia, but a continuation of our human history. Because with the collapse of the idea that the human condition could be different, a great deal was then lost, rather it bears resemblance to early science fiction like Metropolis, where everything is sad and gloomy, and you don’t want to live in a world like that. That is one of the basic questions I often ask myself, what actually happened in those years of “it’s all getting better.” And today you feel like an anachronism; there is no alternative because it is not en vogue and the idea of the future is absent.

Exhibition view "we dreamed of a past future | Andreas Werner" VILTIN Gallery Budapest 2019, Photo: VILTIN Gallery / David Biro

Exhibition view "Obsession Drawing", Universalmuseum Joanneum – Neue Galerie Graz / Bruseum 2018, Photo: Universalmuseum Joanneum / N. Lackner

Exhibition view "Ticket to the moon", Kunsthalle Krems, Photo: Kunsthalle Krems / Redtenbacher

Your exhibition Galaktal at Kunsthalle Krems opens in November 2021. What can we expect?

It is a space focused on my present work process and I present my graphic work and also an installation. The works will hold a discourse with each other and span a universe, and viewers will find themselves in this universe; they can walk through it and gain their own insights, or rekindle thoughts, dreams, and fantasies, thinking “what if?” The title is a game, because I think it is terrible when titles explain something. “Galaktal” is a neologism and this composition explains nothing, you have an idea in your head, yet that is all you know.

Does that mean we are entering your universe?

Exactly. But as soon as you enter this universe, it is no longer my universe, but becomes yours. That will be the most beautiful thing, when we will fly through the stars together. (laughs)

Interview: Marieluise Röttger

Photos: Maximilian Pramatarov