In her work across different media, Anna Jermolaewa, born in Leningrad (USSR), has demonstrated again and again that she is a keen observer of human life, its societal conditions and political preconditions. As an original member of the opposition party Democratic Union and co-editor of their illustrated weekly, she was accused of anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda. To avoid arrest, she fled in 1989, via Poland, to Vienna, where she lives today. For the Austrian contribution to the 60th Venice Biennale, Anna Jermolaewa covers a broad spectrum ranging from her personal migration experiences to forms of non-violent resistance against authoritarian regimes.

Anna, where and how do you work?

I mostly work on the computer, which allows me the freedom of working almost anywhere. For example, I find the most comfortable place to edit video is in bed. However, I have a variety of media I work with and particularly appreciate my studio in Upper Austria. I can concentrate well in the countryside, unless one of my cats is knocking something over.

Would you describe yourself as a video artist?

For a long time, I was called a video artist, but I mostly work conceptually. I moved away from creating standalone video works long ago. I mainly create installations, and videos are sometimes a component. First comes the concept, then I decide how to realize it, whether it be through drawings, videos, objects, etc., or a combination of various media.

Speaking of concepts, early in your career you cut most of your paintings into pieces and displayed them in a pile, as a new work. Was cutting up these paintings a liberation?

I think my early paintings were quite bad. I’d applied to the Academy of Fine Arts five years in a row and was rejected every time! Breaking away from the works that emerged from my academic studies in the Soviet Union was a big step. It was also a question of space: suddenly all these huge canvases fit into a bag!

Do you think art is always political?

I agree with Hans Haacke: “All art is political, and then there's politically committed art.”

Do you feel the need to give people something to take with them?

To actually influence people's lives with art…that’s an important goal for me. For my video work Singles Party (2003), I invited my single friends to a party where they had to dance with an orange. When I show the video of the party now, I tell people it's just a documentation because the actual work is the couples that formed that evening. Another example is back to the silk routes (2010), which I did for Wiener Festwochen (Vienna Festival Week). It's about vendors at Naschmarkt (a street market in Vienna). Whenever I bought something from certain stands, the vendors spoke to me in Russian. I found out that most of them were Bukharan Jews from Samarkand. Many of them hadn't been back for twenty or thirty years. For the work, I traveled to their homeland and brought them back whatever they wanted.

Like what, for example?

They usually asked for pictures or videos of their houses, their parents’ graves... I worked through the lists they gave me and showed the result on a large screen at the Dr. Falafel food stand at Naschmarkt. They were very touched, and I had the feeling that I’d done something important.

I remember your work at the Venice Biennale in 1999, Hendl Triptych (1998), where you can see chickens roasting on a rotisserie grill.

I was in my first year at the Academy when curator Harald Szeemann became aware of my work. Hendl Triptych was one of my first videos, and he showed it at the Academy's annual exhibition. A year later, a fax arrived at the porter's desk at the Academy’s Semper Depot location asking if I could also show it in Venice.

At Biennale Arte 2024, you will be showing a new work that turns the ballet Swan Lake into a form of protest.

Yes, the work is based on a code that’s perhaps not so well known outside of Russia and post-Soviet states. If you grew up in the Soviet Union and saw Swan Lake broadcast on television in a loop (sometimes for days), it meant there was going to be a change of power. The government used it to distract the populace during political instability, as a form of censorship. I saw this happen three times as a teenager. On the days that Brezhnev, Andropov, and Chernenko died, the ballet was on the TV screen all day instead of the usual programming. Meanwhile, the change of power was being finalized on the upper floors. One of my new works for Biennale Arte 2024—in collaboration with the ballet dancer and choreographer Oksana Serheieva—is titled Rehearsal for Swan Lake (2024). It’s a video and installation in which Oksana leads a troupe she assembled in rehearsals of selected scenes from Swan Lake. They are rehearsing for, invoking, regime change in Russia. We are repurposing the ballet into a protest against Putin and his murderous regime, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Are you interested in the ballet?

I wasn't at first, but I've learned to love it. Now I've seen how incredibly strenuous it is and the amount of dedication involved. During our shoot, I’d see the dancers pull off their shoes during a break and sometimes their toes would be bloody. When the break was over, they would pull their shoes back on and get right back to rehearsing. They are tough as nails. Usually, we only see the end result: beautiful, graceful, with an almost clinical perfection. What I witnessed while producing this work is the struggle, the process, the mistakes, which makes the “perfect” moments, when the rehearsing pays off, all the more beautiful in my eyes. I will never look at ballet the same after this. Oksana Serheieva introduced me to this world and I’m extremely lucky to have her as a friend and colleague. Oksana and her family were living in Cherkasy, Ukraine, where she ran a ballet school, until Russia’s full invasion in 2022. Her and her three daughters ended up in Vienna and we met through some work I was doing helping Ukrainians adjust to life in Austria. We see this work as an opportunity to combine our “voices”—Oksana speaking through ballet, me through conceptual art—in protest.

What other works will be presented in the Austrian pavilion this year?

There will be six functional Austrian telephone booths in the courtyard, Untitled (Telephone Booths) (2024). They are from the Traiskirchen refugee camp. It is said that the most calls abroad in Austria were made from these six phones. I used one of these exact booths to phone my family after I arrived there in ‘89. They are covered in graffiti of many different languages. They are like capsules of hope…but also despair. They represent hundreds of thousands of people in transit. The refugee center scheduled them for removal and I asked if I could have them. In the Austrian pavilion they’re experiencing a new life.

The theme of arrival, or transit, seems to have been on your mind for a long time. The work Research forSleeping Positions (2006), for example, in which you try to find a comfortable position to sleep on a train station bench in Vienna’s Westbahnhof.

Yes, this work will also be shown in Venice! When my then-husband and I arrived in Vienna, we spent our first week in Westbahnhof, sleeping on benches every night. Since then, they’ve installed new benches, with armrests. In a way the work is a revisiting of my experience, where I try to understand it, analyze it, the different positions, how it felt; however, with the added difficulty the new benches presented. I also wanted to point out how these seemingly subtle changes make finding sleep on them nearly impossible. Research for Sleeping Positions, together with the telephone booths from Traiskirchen, isn’t just simply biographical. I hope that people who see these works together can examine their position towards those in society who are in such difficult positions, those in transit, without a home.

Many of your works also include travel in some way, or at least you must travel to realize them. Traveling seems important to you.

I always want to learn something new, and I’ve found traveling is one of the best ways. I'm not necessarily looking for something exotic because I often find things right under my nose in Austria. I could’ve easily filmed Hendl Triptych in Prater (an amusement park in Vienna), but I filmed it in Acapulco. I find that my gaze is more sensitive when I travel. I love the moment when I lose myself in a city. As the Situationists said, “Lose yourself in the cities.” You have a different eye and discover things because your attention is higher.

Do you have any new projects on the horizon?

My next project is an exhibition in Vienna with Phileas. It will be a collaboration with the class for experimental art that I run at the University of Art and Design Linz and partly overlap with my exhibition in Venice.

Rehearsal for Swan Lake, 2024, Anna Jermolaewa and Oksana Serheieva, Austrian Pavilion, Biennale di Venezia 2024, Photo: © Markus Krottendorfer & Bildrecht

Anna Jermolaewa, The Penultimate, 2017, Photo: Markus Krottendorfer

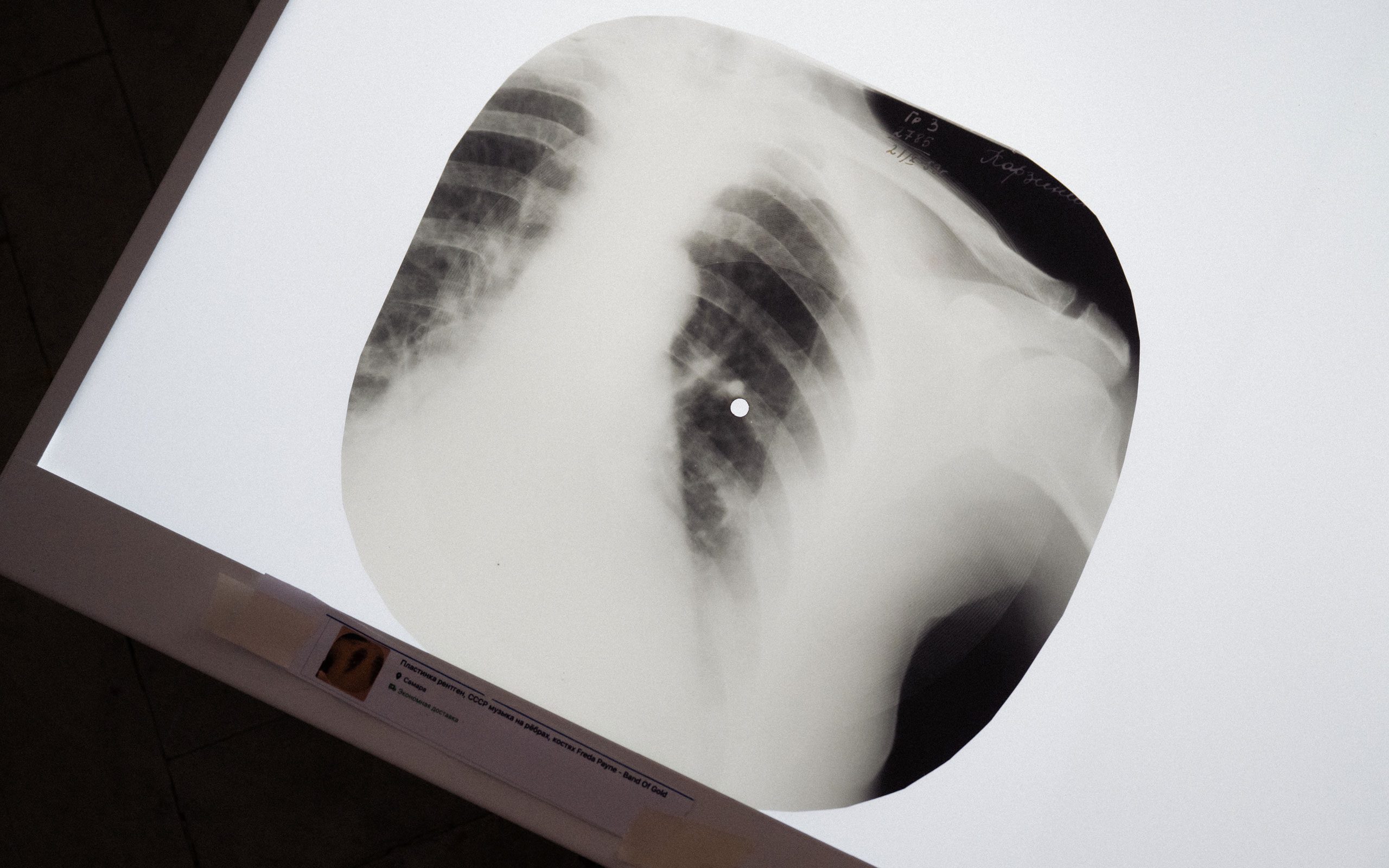

Anna Jermolaewa, Ribs, 2022, Photo: Markus Krottendorfer

Anna Jermolaewa, Untitled Telelphone Boots, 2024, Photo: Markus Krottendorfer

Interview: Alexandra Markl

Photos: Christoph Liebentritt