Anselm Reyle is one of the most internationally renowned contemporary artists in Germany. Reyle’s best-known works include his foil and strip paintings and his sculptures. Remnants of consumer society, discarded materials, symbols of urbanity, and industrial change play a central role in his works.

Anselm, you studied at the art academies in Karlsruhe and Stuttgart. How did you feel when you had the acceptance letter in your hand?

At the time, I applied to three art academies: Stuttgart, Karlsruhe, and Berlin. I was accepted at two of them. I was very happy about that, because this acceptance and art were a kind of salvation for me. The art academy was the first institution where I could get along at all after kindergarten. By hook or by crook, I had gotten my secondary school diploma. Then I tried an apprenticeship as a landscape gardener, but dropped out again. It was a bumpy road. I had always dreamt of making music, even had a band, but that didn't work out the way I imagined either. At the art academies, it took me a while to find my way. I dropped out of my studies in Stuttgart and resumed them in Karlsruhe. There it was free enough for me to settle in. I had interesting fellow students and professors and there were fewer dogmas. It was different in Stuttgart, where I still had to learn how to draw nudes and corncobs. I had developed a phobia of institutions over the years, and Karlsruhe was fortunately different. Who knows what would have become of me without the art academy in Karlsruhe.

Which professors and artists had an influence on you?

My professor at the time, Helmut Dorner, was very important for me, as were the artist Erwin Gross and the sculptor Meuser, later also Günther Förg. I have one of his paintings hanging in my office. Förg influenced my artistic attitude. When I learned that he hadn’t painted some of his pictures himself, I was very upset. But as you can see, that’s how it works with myself now. The things I used to get most upset about have ultimately become the main component of my artistic work.

Your “foil pictures” made you world famous. How did the idea for them come about?

After my studies I moved to Berlin. Karlsruhe was perfect for studying. I could work in a concentrated way, I was able to focus and to develop my own artistic language. But I didn’t see my art in the southern Germany. In the 1990s, a lot was happening in Berlin. There were young exciting galleries and I had numerous connections in the art scene. My girlfriend at the time had close connections to the Städelschule in Frankfurt, mainly to Thomas Bayrle’s class including artists like Thilo Heinzmann and Thomas Zipp, who all went to Berlin later. We did exhibition spaces together. I lived in a backyard with a coal stove in Neukölln, very classically, and I walked the streets a lot. I was very fascinated by the urbanity and the multiculturalism; things that didn’t exist like that in southern Germany, such as flea markets, Armenian clubs, and Turkish vegetable stores. One day I discovered a store window that was decorated only with silver foil. It shone and crackled; the foil was a real eye-catcher. When you have no money and want everyone to look, foil is the perfect decorative material – minimum material expense for the greatest possible effect. This I had the idea to use this material for my painting.

How did you implement that?

I experimented with foil in the studio and was somewhat ashamed at first, because I felt that I had done something forbidden or somehow pornographic. Silver foil is a deco material of consumer society, and to use that material for abstract painting was new and scary at the beginning. It’s similar to pop art: things from the store window come onto the canvas. It’s an identical process, only in the abstract.

What is the typical work process for your artwork?

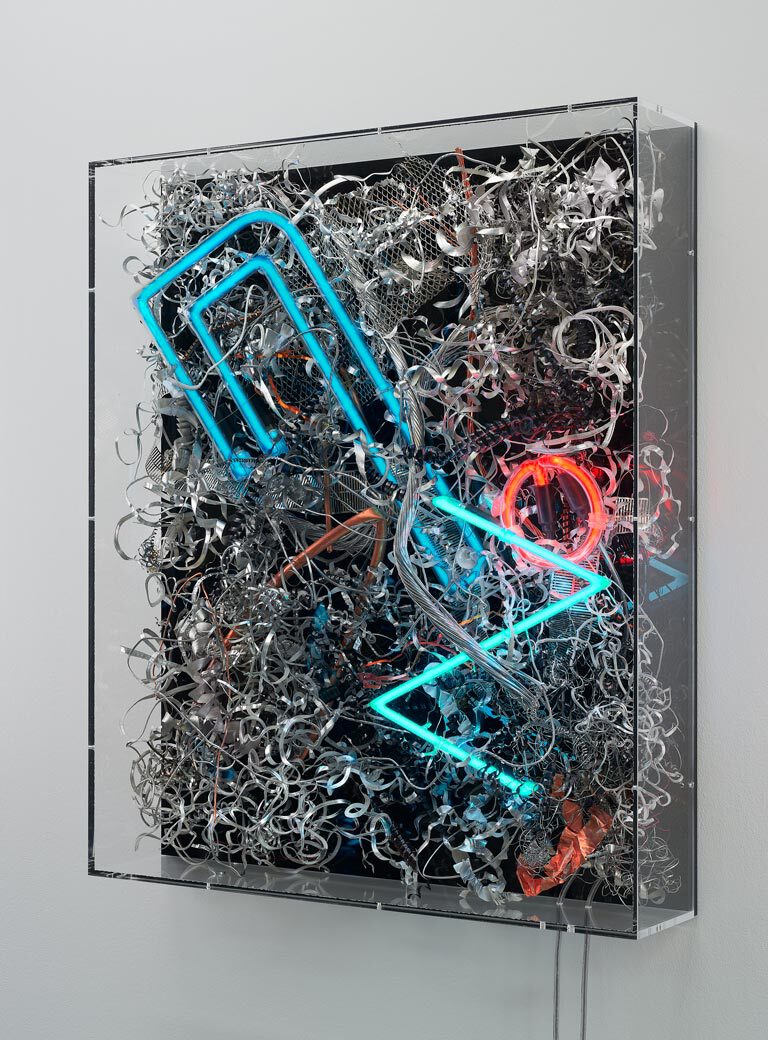

My painting emerges from the process in the studio. In my painting as in my installations, I use things I find. The source is often a found object. The striped painting, for example, as a found object of modernism. I then exaggerate it in regard to materiality as well as color and dimension. For example, a small African sculpture only a few centimeters tall can become a three-meter high sculpture.

A number of media refer to you as a German Jeff Koons, as a pop artist. What do you think of these attributions?

My two references in art history are European Modernism and American Pop Art. I consider Jeff Koons to be the most important artist of our time, not least because he manages to reflect our society in the greatest possible poignancy. You can’t get any clearer than that. The difference between us lies in the main source. I have been strongly inspired by European Modernism and its formal language, while Koons has devoted himself directly and without detours to consumer society. If you look at African sculptures, for example, you come to the conclusion that they don’t have a long tradition in Africa in this form. These soapstone sculptures for tourism have only been around for about sixty years. It is a mixture of African craftsmanship and European Modernism, a copy of the formal language of artists like Henry Moore. I’m very interested in what has happened in a hundred years of abstraction.

And what exactly do you mean by that?

Painting has probably existed for about 40,000 years and has become increasingly detailed and technically adept over time. At the turn of the 20th century, however, painting began to dissolve formally and became abstract within a short period of time. It eventually ended in Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square. Through photography, painting has lost its depictive function. This has occupied me all my life.

Is that also the reason why you ventured into sculpture?

That happened after I left art school. I realized that I’m not an artist who gets inspired by looking inside myself. Rather, I’m motivated by outside influences; things I encounter. In college, I hung fishing nets next to my paintings, or wagon wheels like in the Italian restaurant. That’s how I gradually came to sculpture. Then in Berlin it became more urban.

Which exhibitions have advanced your career the most?

My first solo exhibition in 2002 at the Berlin gallery Giti Nourbakhsch was very important for me, but also the shows in our off-spaces, which I curated together with fellow artists at the time. I ran these together with, among others, Thilo Heinzmannfrom Frankfurt and Claus Andersen, who is now a gallery owner in Copenhagen. Claus Andersen was also an artist at the time, and we sat up our own program with quite new impulses for the Berlin art scene. And later, of course, there were important international exhibitions of my work, among others at the Modern Institute in Glasgow, at Almine Rech in Paris and Brussels, at Gagosian and Gavin Brown in New York. Institutional exhibitions such as at the Neuer Aachener Kunstverein and Kunsthalle Zürich were also important steps in my career. Later, I participated in a group show at the Palazzo Grassi that was a great success. I was able to arrange the rooms myself together with my favorite artist, Martial Raysse, a French artist from Nouveau Réalisme. The curator suggested our work would work well together. She thought I didn’t know Raysse, yet he had been my personal favorite artist for a long time. Also important for my career, of course, was the solo exhibition Mystic Silver at the Deichtorhallen Hamburg in 2012, as well as the recently concluded show After Forever at the Aranya Art Center in Qinhuangdao – my first major solo exhibition in China. I was given the opportunity to arrange the entire museum in its interesting architecture. The museum itself has only existed for a year.

In 2014, you put art on hold for a while, only to resume it in 2016. How did this decision to start again with art and to change your style and way of working come about?

There had been such a routine creeping into my work. One had one’s trademarks, stripe and foil images, which were requested again and again. Of course, this led to a strong routine and at some point I had made enough of them. I felt the need to go into myself and find out whether I wanted to continue and if so, how.

And what was the result of this reflection process?

I just wanted to get away from this big structure that I had built up. In 2008, I had about fifty employees, which I also had to reduce because of the economic crisis, which was very difficult. It was a big construct, and I came to a point where I wanted to get away from everything, to set a new course. As part of the collaboration with Franz West during the last three years of his life from 2010 to 2012, we playfully developed over thirty works together. We sent each other our studio scraps and then continued to work on them. It was a very spontaneous, open process that was an inspiration for me to rethink my own way of working. Actually, that was also inherent in my work, but this approach had been somewhat lost in part due to the large apparatus of my studio. I needed this break to find that again.

What is the meaning of art for you?

Art is an important part of my life. It is my personal language and form of expression. It is above all the immediate experience that fascinates me about it.

The remnants of the industrial and consumer society then became your central themes?

That also developed, I never approached it conceptually. As I mentioned, I usually came across something like fishing nets or wagon wheels. I then deliberately used these objects as provocative decorative material. That’s how it started that I became involved with the surface and the decorative in the first place. The wagon wheel, for example, has an archaic form and is symbolic of the beginning of our mechanized society. However, it is also a frequently used decorative element. The foils and shavings are remnants and fragments of our consumer world. Art always tells something about the time in which it was created.

What projects are you working on at the moment and what are you planning for the future?

I am currently working on the further development of my painting and in this context I am taking a fresh look at the color and material vocabulary I’ve developed over the past few years. The freer handling of it interests me more than the conceptual at the moment. Likewise in ceramics, where a lot of the unexpected happens. You never know how something will come out of the kiln. I am also currently planning a solo exhibition for a museum in southern Germany, as well as some outdoor projects, including neon installations, façade designs, and sculptures.

Wagenrad, 2001, found object, neon, 40 cm (diameter)

Untitled, 2020, mixed media, neon, cable, acrylic glass, 96 x 81 x 17 cm

Photo: Matthias Kolb

Untitled, 2018, mixed media, neon, cable, acrylic glass, 195 x 156 x 26 cm

Photo: Matthias Kolb

Harmony, 2008, bronze, chrome optics, plinth with macassar wood veneer 170 x 170 x 75 cm, plinth 54 x 160 x 78 cm