The scene for contemporary art in Europe’s North is expanding and developing new dynamics as international collectors are watching the scene. With Nordic Notes we regularly cast the eye on the Nordic art and cultural scene, portraying its important actors.

Finnish artist Antti Pussinen is a multidisciplinary visual and sound artist based in Berlin, Germany. In his artworks he uses analog and digital electronics to recreate impressions of phenomena found in nature and the universe. His latest research explores the boundary between wave physics and real world using sound and waveform imaging.

Antti, why did you choose Berlin?

I came for an exhibition. At the time existed a three-year gallery project that exhibited Finnish artists in Berlin and I arrived for my first exhibition. That was on February 28, 2010. I came with my girlfriend, now my wife. And I said: Hey, let’s stay here. It’s all so cheap and beautiful here. First, we committed to half a year, then a year, and now it has already been 14 years.

You came for the art. But how did it all begin?

I was very young. I was seven years old when I discovered the Museum of Contemporary Art in my hometown of Tampere, the third largest city in Finland. They had a temporary exhibition space just around the corner from where I grew up and at the time, they had made the super cool decision that all children could visit the museum for free. Since then, I became a permanent visitor.

Was there a key moment that led you to art?

At around 1990, I first saw an exhibition of early video and kinetic art there. Quite postmodern! And that was very impressive. At the time, I was walking past it with my friends, and we spontaneously went in to see what it was.

Did you already come into contact with art at home?

Not really. There were a few graphic works by a Finnish artist from the 1980s hanging on the walls and there were books on art history and Modernism, but nothing on contemporary art.

You mentioned video art. What impressed you about it?

There was no television in our household, but my grandmother had one. However, I wasn’t used to sitting in front of the TV every day. Even today, I don’t watch TV.

And what triggered your experience in the museum?

Looking at the museum monitors, I thought, this is crazy. Such a beautiful building for these things that don’t make sense at all! And in one of the films, I saw a sculpture installation with a body within which mice and rats were living in tubes. And I took the headphones and just thought, that doesn’t make any sense. That’s absurd. At the same time, I instantly realized it’s superbly done! Just perfect! It was such a cool space with a sacred feeling – just as in a museum.

That’s absurd. That doesn’t make sense, you said. Has this become a reference regarding your own work?

Yes, in the past even more than today. I considered it absurd because I wasn’t aware such a thing existed. It was completely new to me at the time, and it was so impressive, a bit like the advent of the Internet.

How did you learn how to use the Internet?

At home we had the first Internet connection between 1995 and 1997. Finland had this technology very early and we had already had contact with computers and the Internet at school. Net-Art existed already at the end of the 1990sand I was involved in it too. I considered these websites, which used virtual installations to be works of art in themselves, really great pieces of early computer art.

And how did it continue?

However, digital and art converged for me much later, at around 2004. After my small excursions into computer art, I first wanted to learn how to draw. I sat down and tried to improve my drawing every day on my own.

How did you go about it?

I am a big fan of libraries, so that’s where I went. I started to choose motifs that I began to copy. Then a book inspired me to draw everything from memory, just as you have seen it yourself. All my school notebooks became drawing books. (Shared laughter) I wasn’t a good student back then.

When did you decide to become more professional?

I was 18 years old when I had the idea of applying to an art academy and I was accepted on my first attempt with my application portfolio. Friends of friends of mine were artists and had given me tips beforehand.

What was your first impression and what were the consequences?

I started there assuming I would paint now. However, there were people who were better than me. So, I began training as a craftsman in different media. Craftsmanship had always been my thing. I first learned installation art and land art in the specialist classes. Spatial installations were my thing. Eventually, I arrived at media art.

How did your parents perceive your development?

My mother is a medical doctor, and my father is an architect. So, when I was 18 years old and embarked on this path, they didn’t think it was such a good idea. They told me quite clearly that it would be difficult. And they were right – it is very difficult! (Shared laughter)

But could you have imagined doing something else?

I was quite good at snowboarding and had initially considered doing something with it. But in a competition, I realized that I was more scared than other participants there. (Shared laughter) I had reached my limit, but they weren’t afraid.

You come from Finland and speak about borders. How do you see the Finnish people?

(Laughter) Friends tell me, you are not a Finn! Because I talk so much, don’t like ice hockey and don’t drink... (Shared laughter)

Are there elements in your art that are distinctly Finnish?

Yes. Lots of white. It’s a bit of that Minimalism. I realize that I am influenced by the vast horizon in nature, particularly obvious when others say that my art looks so Scandinavian. I really like to be out in nature a lot. It’s the order in the chaos there that attracts me. Just as you find it in my work.

Isn’t it squaring the circle to want to bring order to chaos?

In nature, as in physics, there exists a complicated set of rules. It looks complicated, but it always follows a system. For example, why do trees grow as they do or why do waves move as they do in water?

And applied to your art, that means what?

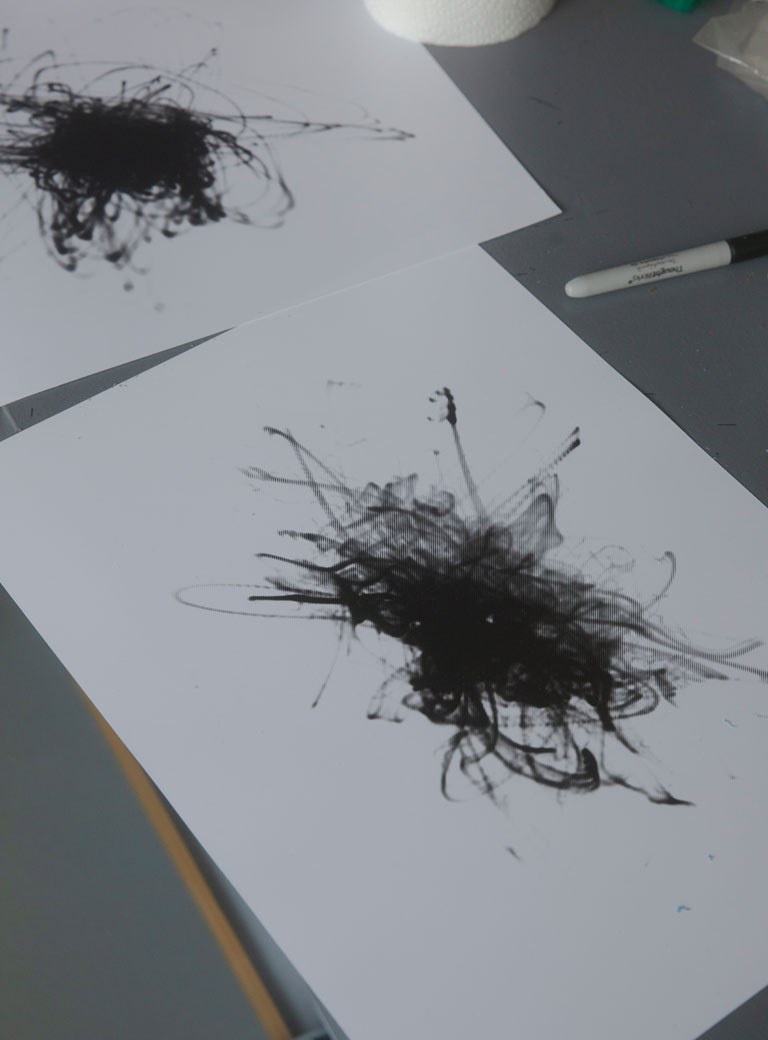

With the sound wave photograms that I now make, I can control what happens. And yet, there is always a huge element of chance. And it’s always a surprise for me, too, what comes out of it.

Are you talking about the narrative of art?

Yes. About the aesthetics in the picture, but more concretely about what is emerging from it.

And what is emerging from it?

Analog art. In all my works there is nothing digital. Although I am using a digital device when I take the pictures, my works are created from light and chemistry.

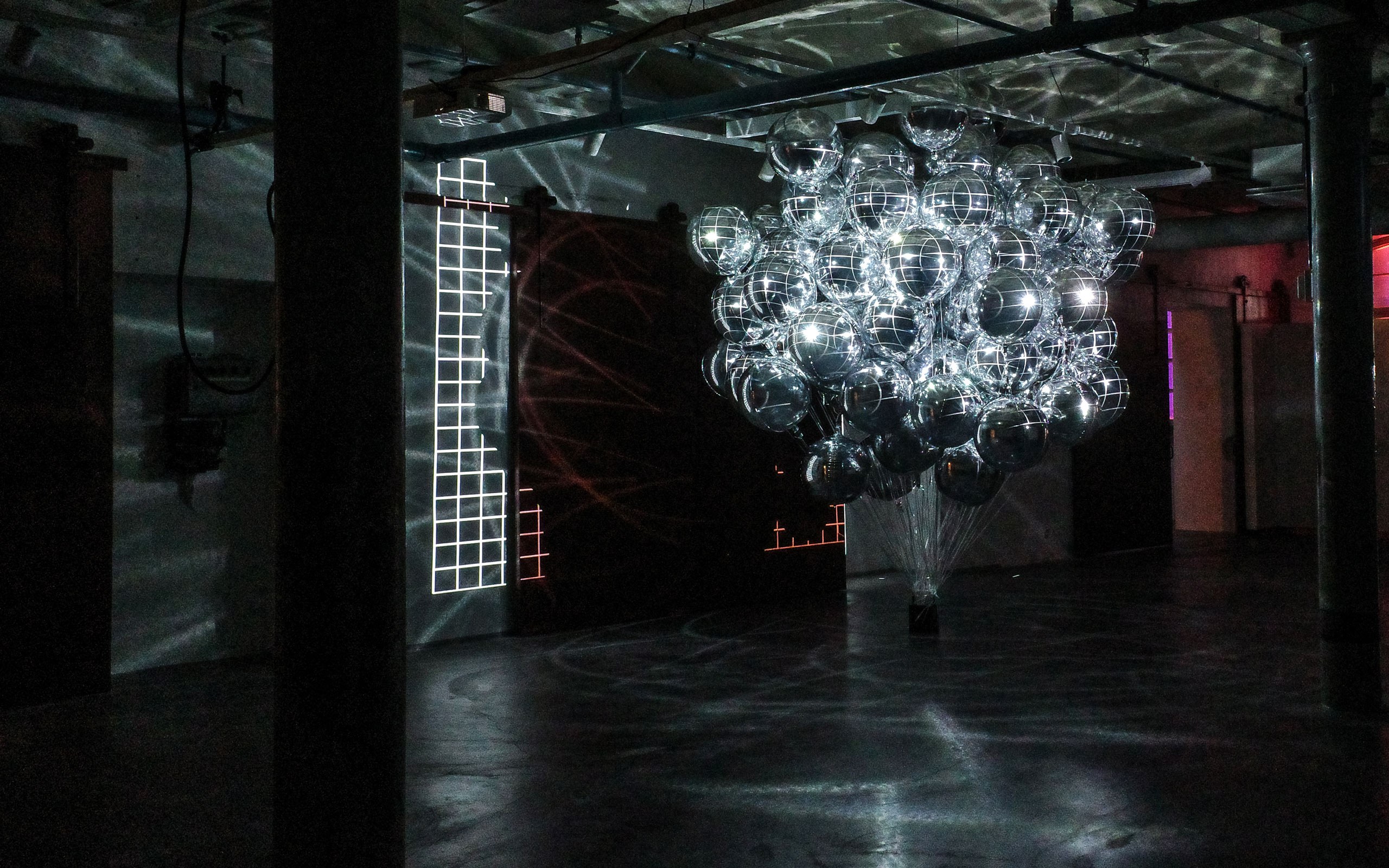

Antti Pussinen, installation view of Global Keystone, Projio, Tampere (FI), 2023

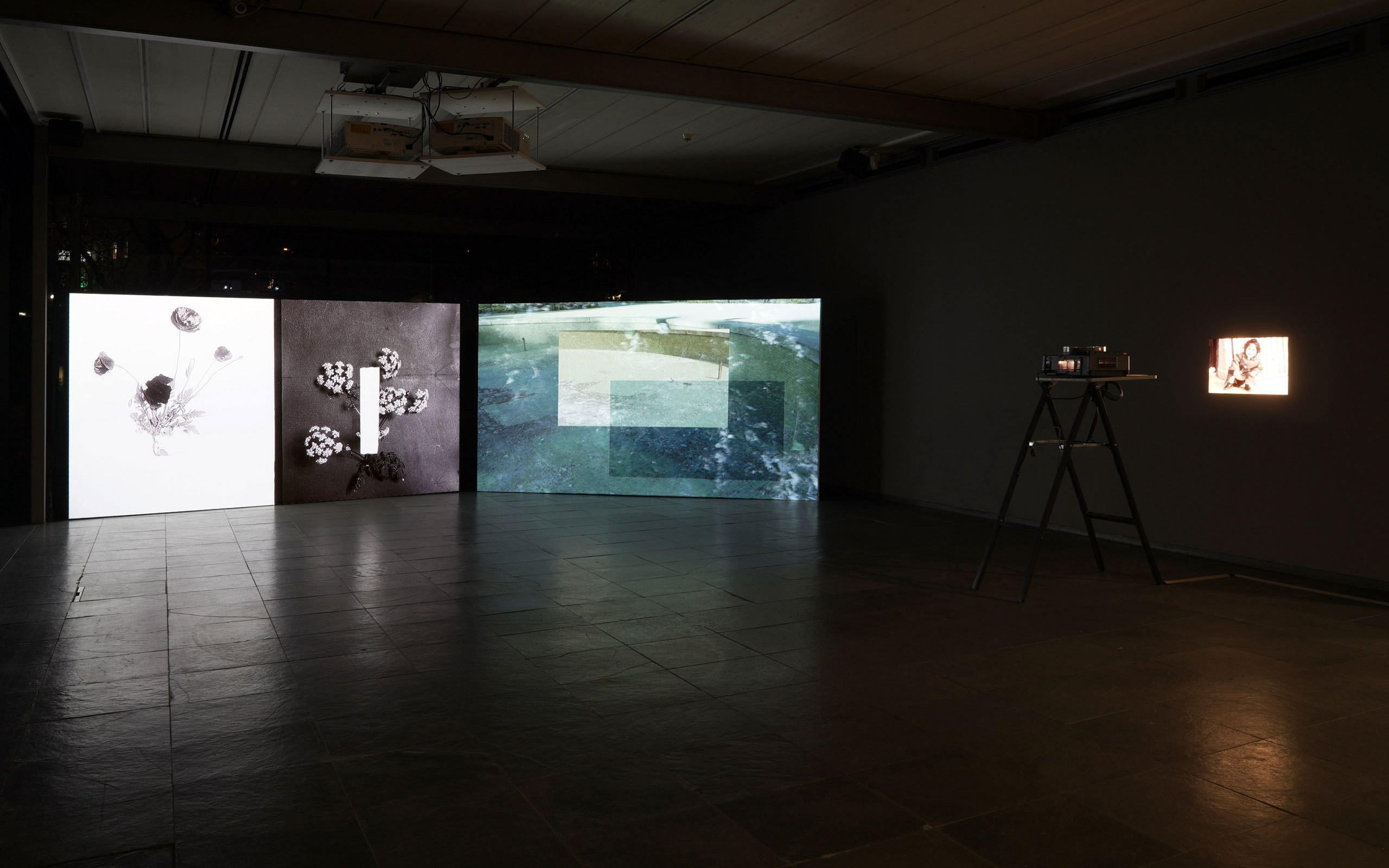

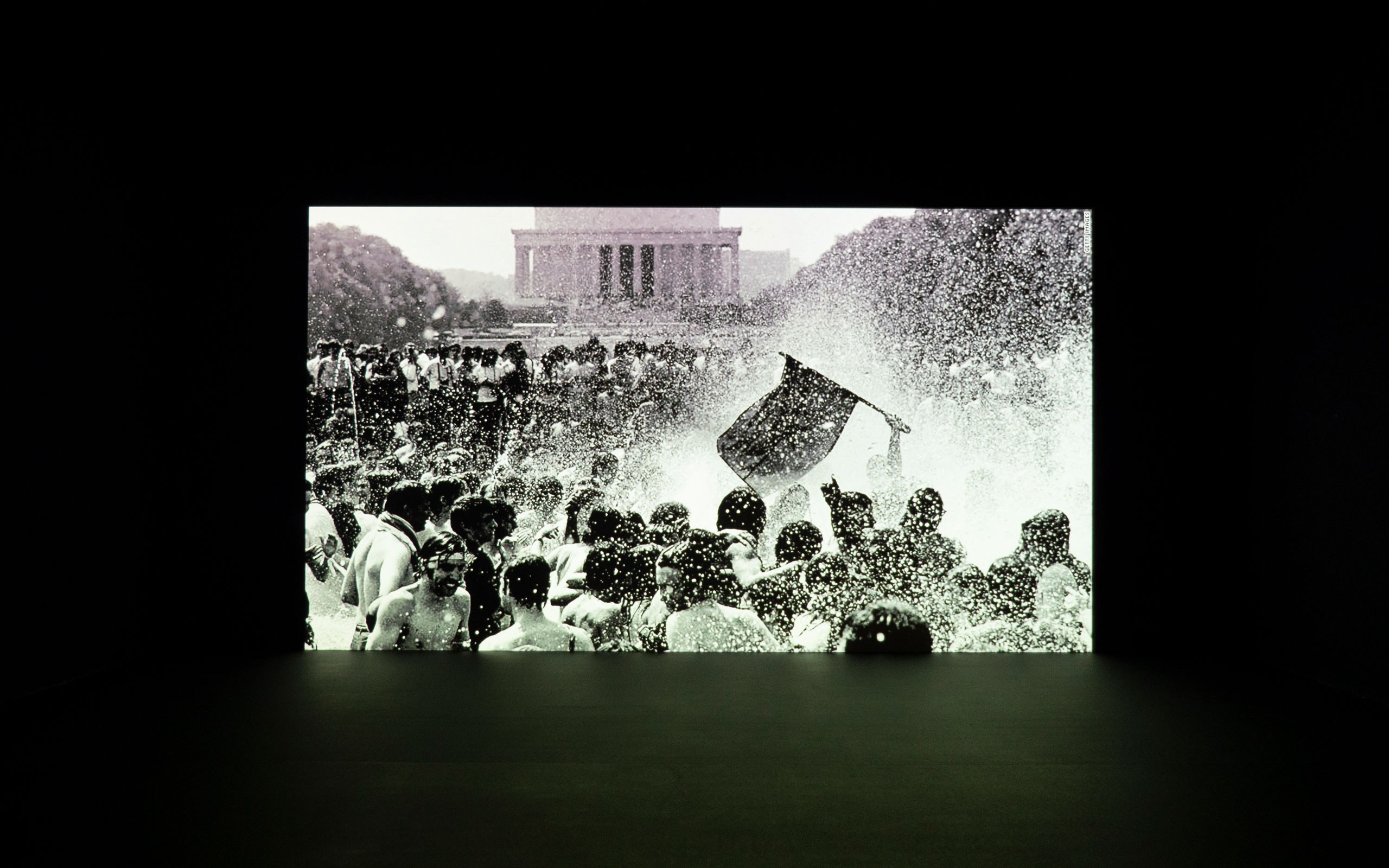

Understanding love in 9 languages, installation view, Luisa Catucci Gallery

What exactly is your production process like?

I have developed a machine, or rather a technique, in which I use old tube televisions. I take them apart and use the screens. Inside are the electron emitters. I generate electromagnetic fields there, which I control with amplified sound signals. When the sound beam passes through the electromagnetic field, it bends in one direction. The beam contains so much energy that the beam that hits the photographic paper immediately exposes the silver paper underneath. The sound frequency is quite high, moving several thousand times a second. This is how photograms are created.

And what do you use as sound generator?

I use synthesizers. I have a few of these from the 1970s.

Does music play a role here?

Not really, more just sound. In my Berlin exhibition, I recorded human voices speaking words. It has developed into a series with nine different people speaking in their native languages and the word love.

Why love?

I wanted a word with a strong meaning to make this visible in my photograms. I figure I will continue to work with words and, particularly, with languages and their meaning. I also want to make progress in my concrete photographic art. However, I also enjoy making sculptures and spatial installation.

If you were to be assigned to an art genre, where do you see yourself?

Even though I make sculpture, I am not a sculptor. Nor do I consider myself an installation artist with my installations, and my photograms don’t necessarily make me a photographer. Good question! (Laughter)

What are you then?

I am simply an artist because I think it from the result. At the moment, it’s my photograms that keep me busy. And I don’t know what will come next. In November I have an invitation to a Light Biennial in Finland, where I will be showing an installation in an old factory. I like doing such projects too. But that doesn’t make me a media artist. I’m just a project artist! (Shared laughter)

What is the challenge here?

As a project artist, everything is always new and interesting for me. I just like to learn. I love learning new things.

How do you approach art history in terms of referential aspects? I associate photograms with Bauhaus and the artist Christian Schad…

Yes, but I shall look at the references to my work in art history later. I first have to create my art and in doing so I don’t want to be influenced, I want to find my own language. It is easier if you don’t know anything! Later you can see that you are somewhere in the big story (points his index finger in the air). Even when I work for new exhibitions, I do not look at what other artists do. I want to keep my head free for my own thoughts and not be drawn into any comparisons.

And the insight gained from this approach?

In retrospect it certainly happens that strangely enough similar things have been created by other artists, because one live in the same era. However, it happens unconsciously. But now I have time to plan something new for my exhibition project in Cologne. Last year, I worked with my photograms. I guess I will pursue this direction again. I think, it will continue…

Do your works get titles and how do these come about?

The decision is always made very late. Usually, the day before the press release has to go out. Even if I’ve been thinking about it for the entire creative process, I decide at the last minute. No title – is not an option for me. But perhaps I still must find a system. (Laughter)

There is art and there is the market. What do you think about the system of the art market?

I’ve always tried to stay away from this market. It exists and it is important. And it isn’t necessarily nice. (Laughter) But it enables me to make a living. However, I actually want to make my art as freely as possible.

What makes your art special?

My art has to do with the power of nature and physics, but also, with a feeling of insignificance. Everything and I are very small and in the big picture nothing makes sense, everything is meaningless. And that is exactly what I consider very beautiful – in fact very liberating and calming. And that is the main idea and the starting point of my art.

The window here is open and we heard a machine noise for a brief moment. This sound will never come back. So, is it also about transience?

At this very moment, that sound was part of our reality. It has passed. I try to capture phenomena of this supposed meaninglessness and make them visible through my photograms. And through a chemical process, they actually remain in reality. The process actually changes something. The photons and other particles of the beam of my technique cause them to form an emulsion on the silver gelatine paper. It changes the silver oxide and turns black. I want to capture these moments.

In a nutshell…

I want to freeze meaninglessness!

Understanding love in 9 languages, installation view, Luisa Catucci Gallery

Understanding love in 9 languages, installation view, Luisa Catucci Gallery

Understanding love in 9 languages, installation view, Luisa Catucci Gallery

Interview: Sebastian C. Strenger

Photos: Katharina Poblotzki