The scene for contemporary art in Europe’s North is expanding and developing new dynamics as international collectors are watching the scene. With Nordic Notes we regularly cast the eye on the Nordic art and cultural scene, portraying its important actors.

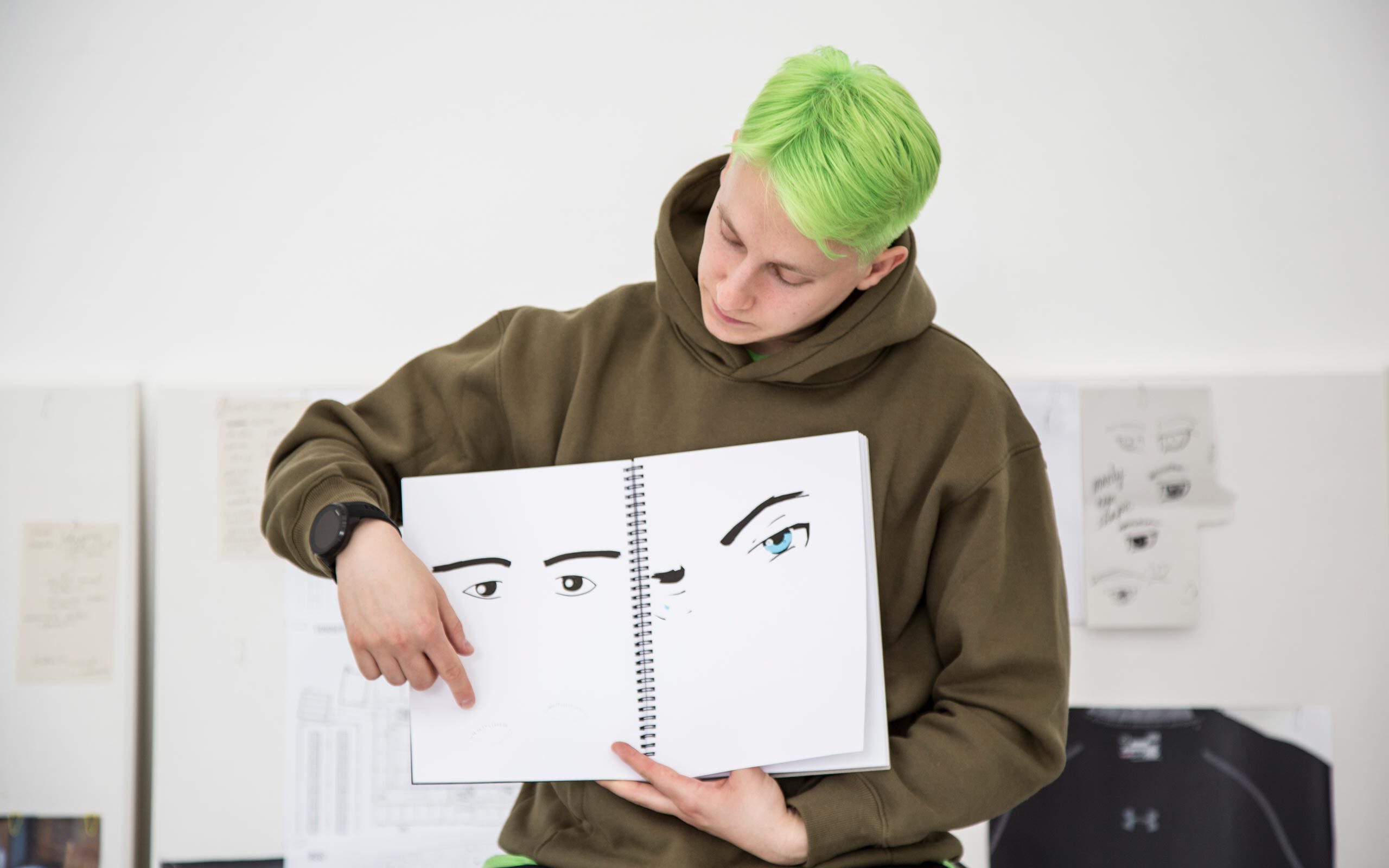

What if your whole life were a performance? Queer performance artist Artor Jesus Inkerö dives deep into traditional forms of masculinity in their long-term performative research. Their infiltration into the subculture at the gym led to a transformation that had ripple effects far beyond the quest for muscle gain. Inkerö’s completed pieces of art, videos, and installations are impossible to comprehend without understanding the full process of bodily transformation that led to the art works. Inkerö is back in Amsterdam after a longer period than originally planned in Helsinki, alternating between their childhood home and the apartment they share with their partner.

Artor, there is no other entry into your art than talking about your ‘bodily project’. You started working out at the gym, from scratch, in 2016.

My bodily project is a performance, which I use as a platform to create art. In that I put myself through everyday transformations of masculinity, like bodybuilding, diet, language, and dress. My art works mix the everyday life, all the stuff that’s going on in it, and myself as a queer person, into a series of works that try to present a version of the world we live in. I shape things into videos, photographs, sculptures, and installations. My performative processes often happen in places where it is not necessarily viewed as art by the audience, when I’m working out, when I’m eating, browsing social media, riding a bike. The everyday world in which I live, is shaped artistically by the things with which I’ve chosen to surround myself

Talking about the everyday and that with which you are surrounded. You have neon green hair, resembling that of music artist Billie Eilish, is she an influence right now?

She totally is an influence on me. Her music is great, but my admiration has to do with how Billie is using her platform to talk about her body in relation to the music industry and the standards that women face. She has been very public about how she wants her body to be presented. Other celebrities too have had their bodies observed intensively by both the media and the public, for example Justin Bieber, Kim Kardashian, and Caitlyn Jenner; it’s an interesting discourse with regard to what I do to my body and to myself.

During your bodily project you produced both photography and videos. Those aside, the project itself WAS the work of art. Did you document this somehow?

I try to document everything. I film with my phone all the time. It feels like I have a chronic self-FOMO (Fear Of Missing Out). I want to have the chance to go back in time, to scroll through my phone and see myself through time. I record things in my diaries as well.

Is this rigorous regimen of documenting your life somehow connected to the habit of keeping track of your progress at the gym?

It started out as noticing how bodybuilders tracked their progress, so I began tracking everything, too. I love the idea of having an option to dive into all that information one day. This is something I still haven’t done, but I’m aware of my fascination for archives and data, and I’ve been collecting mine since 2016. My primary diary is for keeping track of my emotional world and to look at how my work affects my state of mind. My secondary diary is for fitness. I measure basic stuff like my weight and other boring things. Sometimes I just measure the girth of my wrist to keep on track of that.

How did the process proceed?

I began as being very focused on the bodybuilding subculture when I started my bodywork. As time went by, I noticed how the lifestyle had become less robotic and had become somehow a more natural part of me. A couple of years into my performance, I reached a point wherein I stopped measuring things so frantically. This led me to explore masculinity in a broader sense and not only from the narrow viewpoint of masculinity in terms of muscularity.

What is the result of your participatory research in the subculture?

The body building subculture taught me many practical lessons. The experience also gave me moments of acceptance. Like once I was doing bench presses and a “bro” walking by gave me a thumbs up. Those are the weird moments when you feel accepted as part of a subculture, but they are also moments of inclusion because of your physical appearance. And then there were also moments when someone asked if I was interested in buying some steroids. When I embarked on my journey my point of view was very narrow and I anticipated that my journey would expand my thoughts on masculinity and of people who are normative. Of course all kinds of people go to the gym, not only toxic macho men. You are hit in the face with everything being so apparently normal. These are typical dads, mothers, lawyers, bookkeepers, and artists, the “normal people”.

Tell me more about your method?

What I needed to work on most was behavior. I did this mostly through observation and mimicry. I wanted to penetrate those specifically masculine subcultures by adapting to become one of those people. You have to learn how to behave and to communicate in the verbal and non-verbal language of the subculture. That’s kind of like the access point, it’s as if you were a double agent.

I find your art to be approachable and very much needed in our time where we are focused on the body. You’ve hit a critical time.

I feel that it’s impossible to talk about the body without talking about identity. Taking as an example Billie Eilish, we can’t talk about her as a mere body, since she is also a person. I find the discourse about bodies becoming deeper as a result of people like her.

Your bodily project has not seen an extension on Instagram. What do you think about this arena for exposing your body?

Instagram is definitely something I use a lot for research. At some point I unfollowed everyone and started following accounts that were important for my research on masculinity, especially specific brands to generate an algorithm that would feed into this character I wanted to become. Even as a photography project Instagram is so interesting, because people choose how their bodies are seen, creating a materialized story of themselves. Still I feel the core of my work is to look into my own identity and use myself as material, as there’s no limitation to that. I can do to myself whatever I want to reach any personal or artistic goal, I can put my finger on.

How did people react to your transformation?

People started trusting me more, asking more for help and assuming good things about me. The weirdest thing I’ve done was when I tried to alienate my friends. I tried to create friendships that would benefit my work and end ones that I felt were pulling me back. It was not only a huge psychological crisis for me to not recognize the need for friendships, but also ignorant and arrogant of me to do that to my friends, and people who trusted me. Partially it was also my friends having a hard time accepting me for what I aimed to be. There was a struggle with reidentifying myself as someone other and then feeling that they didn’t want to be friends anymore because of how I represented myself. I guess that’s why I’m highlighting the importance of the person in the body. All this research in subcultures and body transformations is so linked with my own life and the events that happened there. My work wasn’t just subscribing to a gym and becoming sexy.

You mean the ripple effects were widespread?

It was something I didn’t expect. I cut my hair short and my mom was shocked. I used to have long hair and I more obviously passed off as queer. Her first comment was why did I want to be ugly. It is so weird that my own circle of people rejected me in the beginning, how they made me feel like a stranger, another version of myself. They saw my project as something that was extremely hurtful to me and my identity, which it was. I do acknowledge now that it was more self-destructive than I thought it would be, it’s definitely not recommended from a mental health perspective to do the things that I’ve done, and also the effect it had on the close circle of people that I had. I was surprised how strongly an appearance can even clash with somebody’s political views.

Your project was full on. You lived it 24/7. You said that you did stuff that wasn't good for your mental health. However, you were aware of the downsides and were able to be in charge, right?

If you mean that I was in control of all situations, I don’t think I was. I had weekly breakdowns. The hardest thing I’ve done so far was behavioral therapy. I attended that for 13 months. We worked on eliminating feminine aspects of my behavior and voice, to transform me to be more masculine in a normative sense. We practiced everything from how I produce my voice or laughter in my throat, to the full physical posture and gestures of my body. That was something that definitely tore me apart.

And to process this transformation you went to another therapy?

The changes in my life made me depressed and anxious, so I needed different kind of help. The social life that I used to have completely collapsed. I’m happy I’ve been able to rebuild so many things though.

If you recall yourself from the time before the project, is it possible to go back to how everything was before?

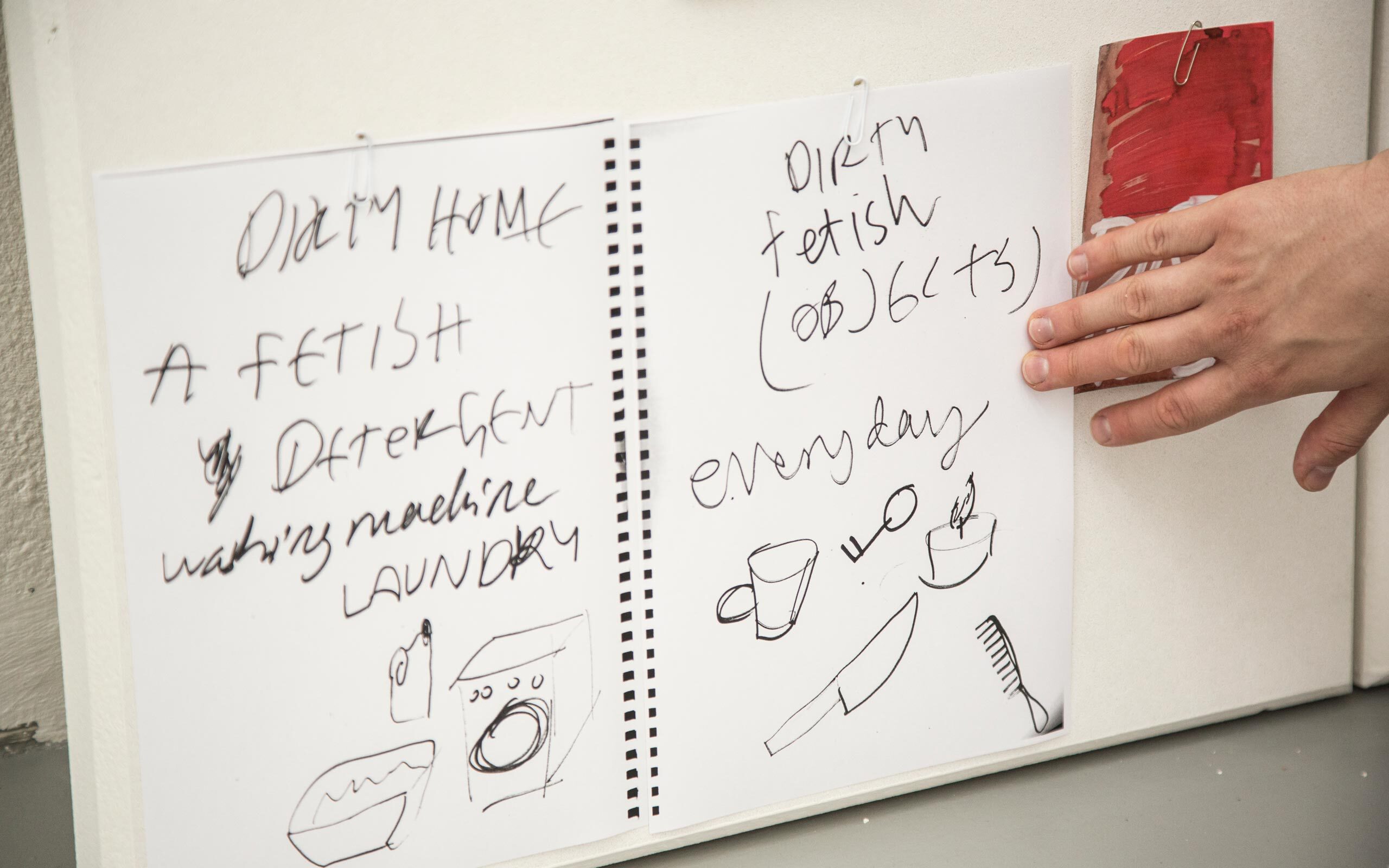

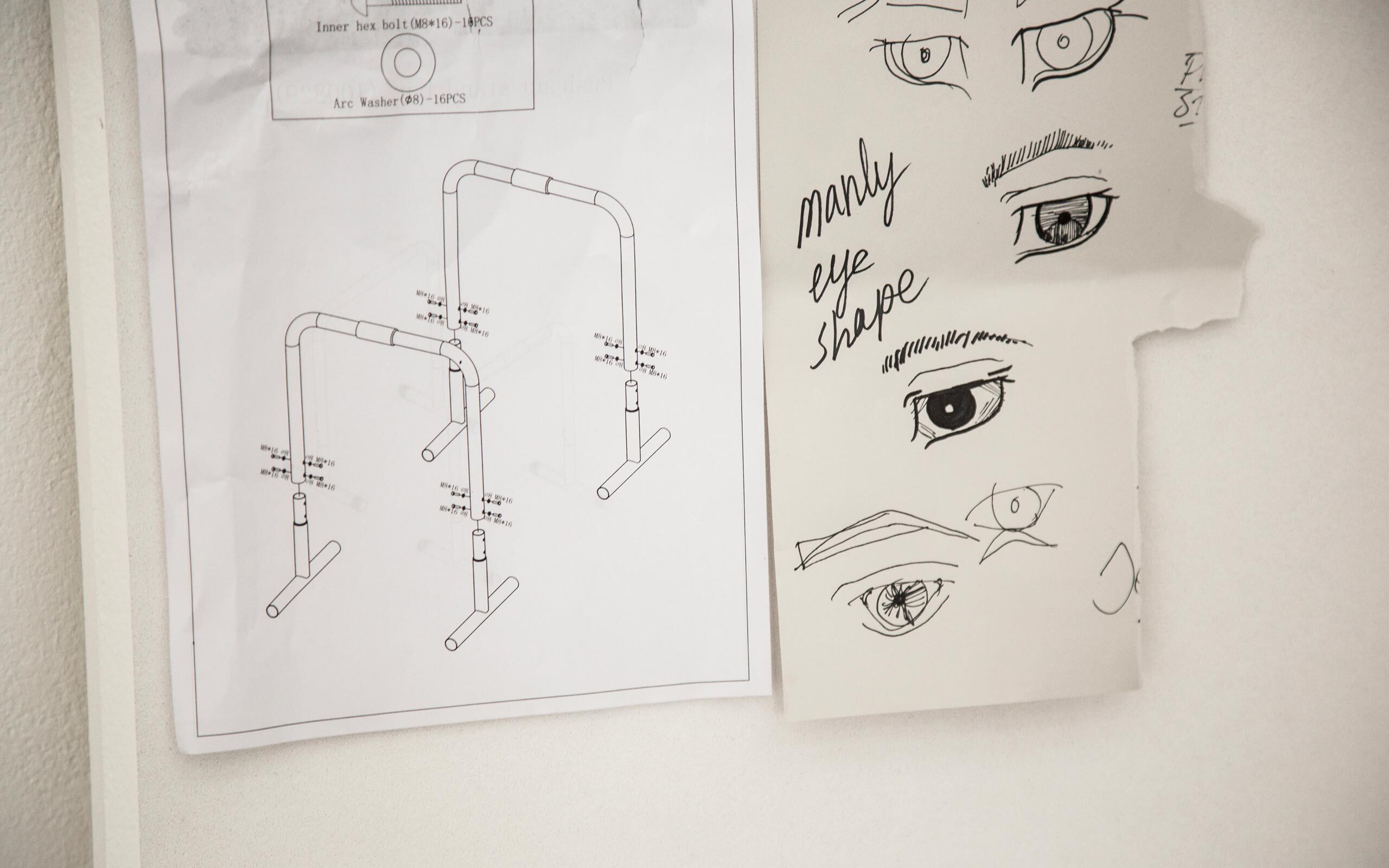

Well, time has passed and my world has changed. New works I’m now working on won’t necessarily talk directly of my body or identity. This spring I’ve been researching domesticity, family, and home. I’ve been looking into very physical structures and objects instead of abstract ones, like contemporary domestic architecture, or the items that make a home. The Western tradition of home and family exclude queerness. How could you even begin to form a home, if you are queer, without it being a representation of a heterosexual lifestyle? And why are queer people seen as nothing but a category of sexuality, when we are so much more than that? Heterosexual people are considered as a natural part of family and society, but obviously that is just the current state of our time, and there’s nothing natural about it. Like the concept of an open kitchen, that is a very popular building solution right now: originally it was to make the wife a part of the family’s social life. As a concept it’s already decades old, but only in recent times has it been implemented as part of the domestic architecture. I also ask are these current structures even valid for the heterosexual cis people either, anymore? Building two bedroom apartments with a room for children assumes heterosexual couples want to have offspring.

Was it important to you that you obtained the acceptance of members of the bodybuilding subculture?

I was curious to make acquaintance with people who share the same space with me. To share a space is crucial because it generates the actual society of that subculture. I did feel as part of a group, and I felt there was a change that happened in me, to be recognized as part of a community. I do think subcultures actually expand our domestic life, and then again expand the concept of a family.

In your video work Swole (2017) you use some of the jargon of the bodybuilding subculture in text messages appearing on the screen. I couldn’t help but notice the homoerotic flare to it?

There is sensuality in what you might call masculine interaction. Men are people, and they act on those sensual and tender moments they share together. It’s a shame that it’s not part of their culturally accepted behavior. Western masculinity is not quite like the open kitchen concept just yet. At the same time, it’s sad and funny. I see bodybuilders exploring their bodies in a sensual way, when they are posing or wearing tight clothes, yet at the same time, men are not allowed to be sensitive.

I liked what you said in one interview about art picking up signals from the time we live in. What do you think future generations will think when looking back at our time with regard to our fixation on the body?

We are all categorized and made into stereotypes. We need to learn to read how our society is structured, and then unlearn those structures. For me to be non-binary and queer is also connected to as what I pass as in life: I enjoy the privilege of being white and of passing as male; it’s definitely advantageous in terms of safety, control, and access. So, to see what your body represents, and what privileges you have, is the kind of moment to be taken out of this day.

How do you see the movement of body positivity, is it real or just an illusion?

Body positivity is great in terms of making discrimination, fat shaming, and unrealistic expectations visible. The discussion around it often lacks the full context of the body, the culture it’s surrounded with, the identity and the person who carries the body. The discussion that exists is still very superficial in the sense that it only shows the struggle that mostly privileged people have about being sexy. To me it feels like a problem that the discussion doesn’t go any deeper, that it doesn’t include disabilities, mental health or the many things that people actually struggle with.

So you see body positivity more widely?

When we talk about “bodies”, as if they were separate entities, it feels that it is so disassociated with ourselves and our identities, as if they are two different things, which they are not. That’s why it’s so weird we only talk about the physical aspects of the appearances of our body and disregard the identity and the person completely.

Do you feel you have broken free of the bubble you were in for a long time?

The bubble of my work still continues. I set myself numerical goals that I would want to reach, and which I haven't, at least yet. The lessons I’ve learned through my work are clichés, but they are also fitting to my hypercapitalist aesthetic. I suppose in the end it is about what’s important and for what purpose.

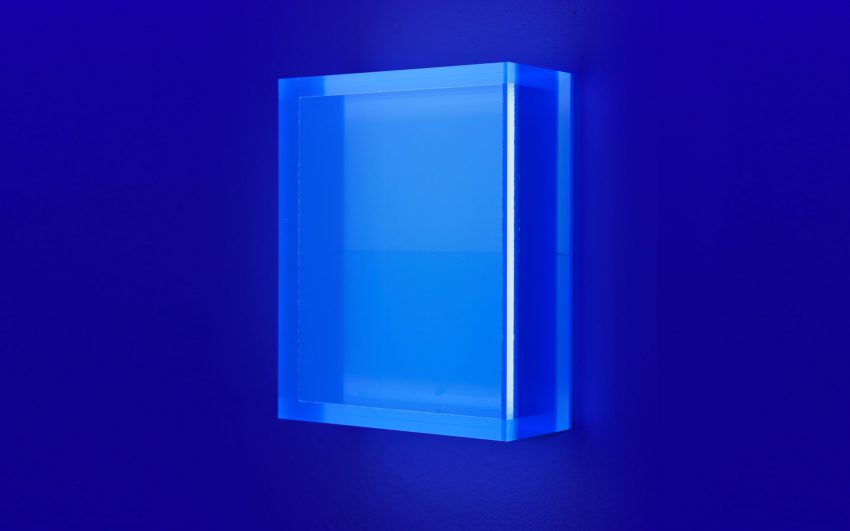

BUBBLE, 2017, Full HD video, sound, color, 18:22, video still, courtesy the artist

JUSTIN, 2016, photo, courtesy the artist

Short Reach, 2019, 4K video, 3 channels, 4 channel sound, color, 11:00, video still, courtesy the artist

Score, 2019, performance, performance documentation at Rijksakademie Open, video still

Photo by Arvo Leo

Interview: Rasmus Kyllönen

Photos: Silvia Martes