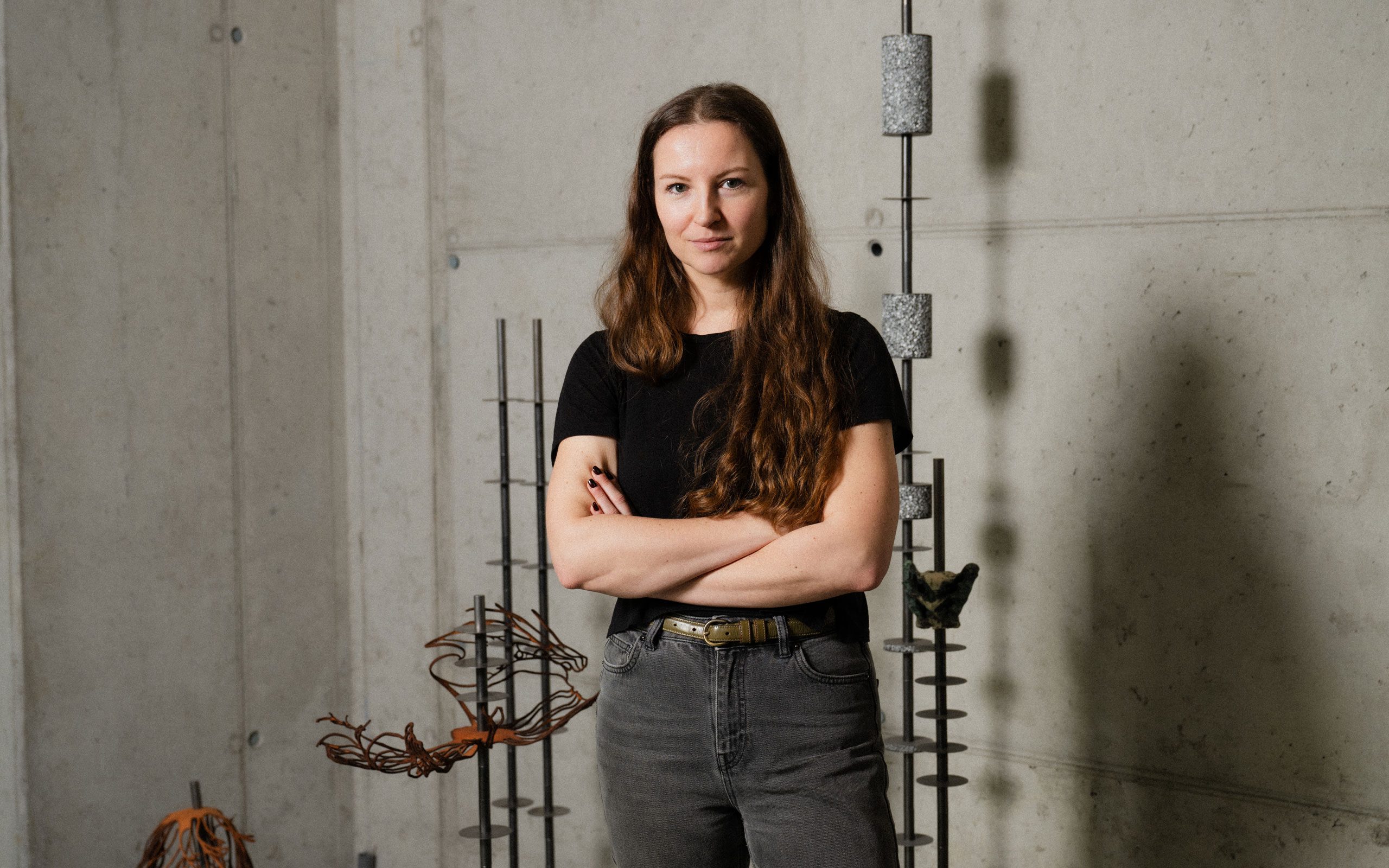

Visual artist Bianca Phos explores connections between the body, society, technology, and our environment across media. Through sculpture in particular, she explores somatic relationships and interdependencies with a focus on vulnerability and power dynamics. By consciously incorporating environmental issues and technological progress into her perspective, she offers a particular reflection on the complexity of our existence.

Bianca, was there one moment in which you realized that you wanted to be an artist?

Art has always been the one constant in my life. The more difficult question is when I actually decided that because it’s not always an easy path; you also have to be prepared to take risks. And that was probably much later, when I applied to the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna.

If art was a constant, did your environment actively support you on your path?

Yes, it did. From a young age, I've always been drawing, everywhere and at all times, and it was somehow always clear to everyone around that I would become an artist. Nevertheless, I first had to find ways to make a life as an artist possible and to finance it. I think that if you really want something and enjoy doing it, you’ll find a way somehow. Making art definitely gives me an incredible amount of strength, energy and perspective. But it’s important to have people around you who believe in you and support you, and I had that.

After all, you studied at various institutions with different specializations – from photography to sculpture. Where do you see yourself now?

I find it really difficult that art is always categorized in this way. I prefer to simply say: I am a visual artist! I actually find it much more exciting to move between media and when different media influence each other in the process, i.e., drawing and sculpture or new media, in my case. Initially, I was concerned with the question of what an image is in our time; I worked with perception, light and the digital image code. The examination of immateriality triggered a strong desire to work with materiality and spatial relations.

What attracted you to materiality?

These questions of materiality have always been there, even when working in digital space. I was looking for disruptive factors in order to better understand my material. Somehow, I am most often fascinated by materials whose fragility impresses me, which have already experienced something, or which are in some way declassified as defective, including rejected orB-Grade goods.

You’ve lived and studied in a lot of places, which seems to be very formative …

Yes, exactly, it was exciting to experience that a unique discourse takes place everywhere and that’s why I think it’s really important not to stay in the same place. In Vienna, I studied video and installation with Dorit Margreiter at the Academy of Fine Arts and later textual sculpture with Heimo Zobernig. In Hamburg I was at the HFBK University of Fine Arts with Simon Denny and in Jerusalem at the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design. So, there were several people, perspectives and points of view in my various studies on how to think about art and life.

Are you drawn away for your artistic work?

Always. It’s all about experiences. It’s a bit like going for a walk. You don’t know beforehand what you’re going to see and experience. I find it exciting every time I go somewhere new. I think it’s also a way of getting to know yourself better, because you simply learn a lot about yourself through encountering the unfamiliar.

How do these impressions flow into your art?

A lot is subconscious… I was extremely impressed by the desert regions in the Middle East, perhaps that’s why I currently work with sand and abrasive mineral particles. I also often work with photos that function like notes. Or photos that I have taken in nature and while travelling, I actually like to use as exhibition teasers.

As an artist living in Vienna, what does the city offer you in comparison to other places?

I grew up in Vienna, Carinthia and Lower Austria; I find this urban-rural mix very enriching. Each place offers something different and unique. Vienna is the place where I built my base, my studio is here, my workflows are set up here, my material suppliers and my network are all here.

In your work, you deal with the body, society, technology and our environment across different media. How do you concretize this network of themes in your works, what are you concerned with?

As an artist, you can ask yourself this question anew every day, and the answers evolve with you. It is a dynamic field, but there are a few constants that I try to grasp across disciplines… I have been interested in embodied experiences for a long time; after a serious accident, I began to deal intensively with biological-medical contexts, but also with psychophysical topics; discourses from areas such as critical posthumanism, but also trauma and disability studies and science fiction literature have influenced me a lot. I often find it disturbing how bodies are evaluated in our society, i.e., how they are devalued in terms of their functionality or ageing. This is a dimension that has been important in my work ever since. Another complex is the organization of knowledge, including embodied knowledge, and relational models of thought, i.e., thinking about relations and ways of relating. I am interested in uncovering how one’s own organism, i.e., one’s own system, is connected to everything else, and how the idea of an autonomous self, disintegrates as soon as you consider the multitude of units communicating with each other.

Can you explain this with the help of a work?

There is something of this in all my works. My sound piece Relational Breathing (2020), for example, which is currently on display in the GRIT exhibition at Zeller van Almsick; which was conceived for outdoor use and was suspended six meters above the ground between four different conifers. In the sound file, I cut together different ways of breathing – there are breathing rhythms from extreme exertion and regained control, for example that of a soldier in battle, and the so-called Ujjayi Breath in yoga, which in turn is very similar to Darth Vader’s artificial breath, which is based on the sound design of COPD. The ultrasonic sound created a very intimate moment, as you suddenly experience this breathing very closely, as if it were in your own head. Everything is connected via the air and breathing. My grandmother struggled with COPD for a long time, so I was already sensitized to the topic ofbreathlessness and what it means to live with this lung disease. With Corona, medical databases were then opened up for open-source use in the hope that an app could be written that would identify these sick breathing patterns using an algorithm. In other words, in the early days of the pandemic while everyone else was stocking up on rolls of toilet paper from the supermarket, I was listening to sound profiles of breathing disorders and started cutting a loop (laughs). Air, or the nervous system, these connections are not visible in this way, and I was also interested in the politicization of breathing or how it is embodied and how bodies can also influence each other through breathing.

That sounds like in-depth research. How do you organize your thoughts right up to the artwork?

A friend of mine, who is an art historian, once joked that each of my works reads like a scientific paper. (laughs) I don’t know if that's the case, but a lot of things come together and then the thoughts and feelings condense and so the decisions come naturally, including how you deal with a subject or material. My work Deep Thrills is also very much about relational thinking and how, starting from the nervous system, everything is in a dialogical relationship with each other. I generally follow this approach in my way of working. I use my own software to collect my thoughts and notes, similar to a method from art history, a kind of index card box system; I try to reduce each thought to its essence in order to then establish relationships to other thoughts. This is very associative, and the relationships can be visualized using a visualization graph; they change dynamically with each new work. It is also a way of capturing thoughts and ideas before they disappear.

When do you consider your works completed?

I’m not at all comfortable with the notion of completeness and I hope that none of my work is ever finished. I think I’m taking it to the extreme right now with the works in which Cutting Instrument appears, including the Deep Thrillsworks, because it is conceived as a system that is constantly changing and, contrary to being closed, is dynamically developing, growing and constantly reorganizing.

How should we imagine your day-to-day work activity, do you outsource certain processes?

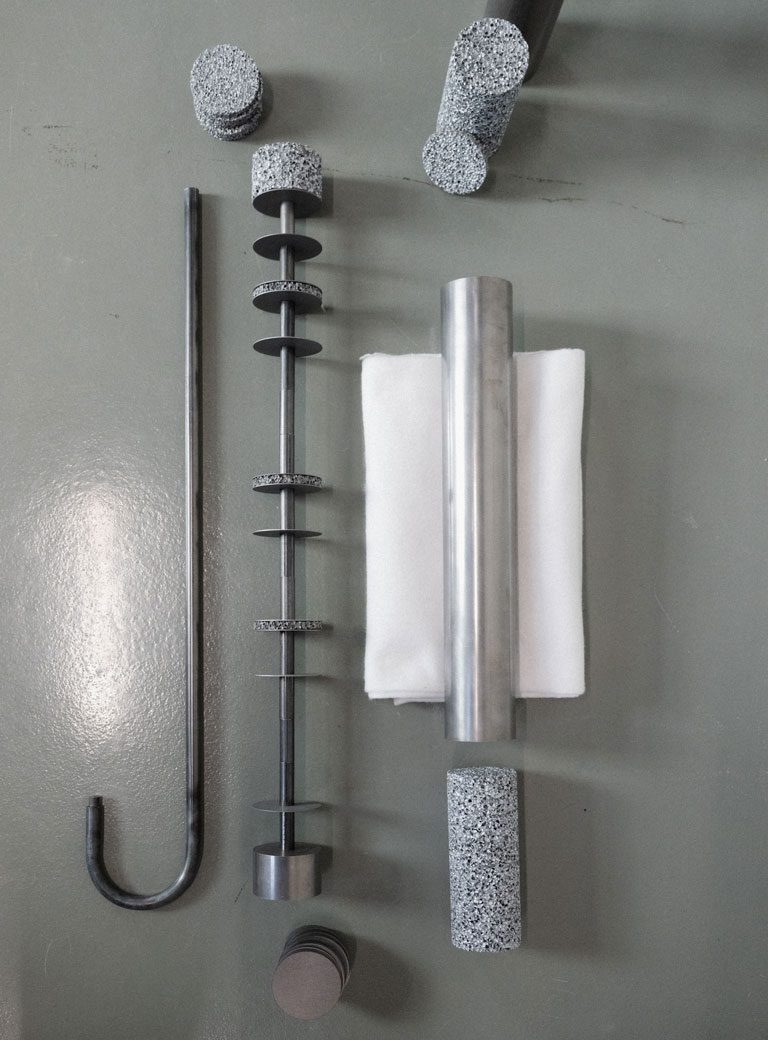

I actually have several work locations, as there are two other production sites where I can carry out welding or laser work. Everything comes together in my studio in Seestadt, where I collect, assemble, and re-collage. I also outsource some things and have now built up a network of industrial and commercial partners. But in this respect, my days are very different… Sometimes I spend the whole day simply researching materials, I like to go to industrial companies and talk to people about materials and their properties and learn new processing techniques or old crafts. Just recently, I visited a sandblasting workshop. I was given various samples of different types of sand, grain sizes, and mineral compositions. But my work process actually starts when I first get up; the first half hour is reserved for drawing and then I don’t know… the best ideas come when I’m in the shower or out for a walk (laughs).

Some of your works, such as the Deep Thrills series, appear strong and robust on the one hand and organic and fragile on the other …

Yes, exactly, I find it intriguing when different forces are in dialogue with each other; also, when vulnerability and the power to injure meet; it’s exactly this dialogue with the material that comes about when I work with it. Every material carries its own characteristics, I mean the material itself says a lot, resonating with associations, a sense of history, but also temporal layers. The temporality in processing is also different; For example, stone is very slow, and wood is terribly fast, and metal suits more my own pace; it is very versatile and changeable, it can be hard, soft, heavy, but also incredibly light, you can bend it or hammer it. Most metals demonstrate resistance, they endure and withstand a lot, while you can also change its inner structure, which I find interesting. I like the fact that it is so malleableandyet very precise. Things often have to fit together, and precision is important here, even with tight tolerances.

What does this precision allow you to do?

It has something to do with system and also system issues. When the individual parts fit together, as in Deep Thrills, I am interested in breaking this regulated, controlled system with all its divisions and subdivisions, in other words its organized structure, by allowing these organic networks to grow out; in other words, also confronting ideas of the clinical with the organic. Interestingly, the material then often appears as something else at first. Many people for example thought the laser-cut leather mesh was rusty metal.

So, it’s a conscious approach to perception?

Yes, when that happens, I find it exciting. Things often appear to be something else, and we perceive this impermanence. The question is, what is truth, and how do we construct reality? I like to work with these inner ideas of something and how you can change them. I believe that you can change and move a lot by changing inner perceptions or images in general, and now is a time when this is important. How can you change the mindset, and how can you create new perspectives? I believe that art has the power and potential to do that.

You work with important themes that can be read socio-politically… Are your works also misunderstood?

Not that I know of, but I think it’s good if everything remains possible. Even if someone writes about my art, they are just individual perspectives on my work, and don’t necessarily correspond to what mine are. I find it interesting to see how someone else perceives it. That’s why I wouldn’t call it a misunderstanding, but rather an alternative understanding. I also have the feeling that I myself that I too am still learning about my work, i.e., my understanding is also in transition.

Are there any reactions you would like to see?

No, everyone can react however they wish. (laughs) When people engage with my work, it makes me happy. Sometimes there is such a feedback loop and I think that communication is an important moment and that a lot happens through it. But I really hope that my work can stand on its own without commenting on it. Maybe even to catch that moment when language reaches its limits.

Some works, such as Relational Breathing, are created for public spaces. What do different spatial relationships allow you to do?

Anything can actually be anywhere; it’s just the relationships that shift. I work with installation, with the perception of my works in relation to the space, and I am also interested in creating a certain atmosphere; interestingly, the public space not only influences the works themselves, but also my thinking about sculpture. It shifts away from a relation to space towards a relation to the world. That is a very exciting process.

You are regularly represented in duo exhibitions, for example with Yorgos Stamkopoulos in Touch Me, Don’t Touch Me (2023) at Zeller van Almsick. What is it like to work with other artists or to be placed in relation to them?

I think it’s great because then a playful game of ping-pong begins; it opens up your own work and it’s nice when a rapprochement happens. I find it enriching to enter into a dialogue with others. Livia Klein is currently curating a duo exhibition with Titania Seidl and me, which is all about this kind of encounter and subsequent dialogue.

What other projects are you working on?

In addition to the duo with Titania, I’m currently working on my next solo exhibition in the second half of the year and on a group exhibition at the Tresor of the Bank Austria Kunstforum, Vienna curated by Bettina Busse and Contemporary Matters, on the subject of storage and memory. And I’m particularly looking forward to my residency at Nida Art Colony in Lithuania, where I’ll be this summer.

Bianca Phos, Sharp Dispositions, exhibition view, WAF Galerie, Vienna, 2023, Photo: Kunst-dokumentationen, 2023

Bianca Phos, Sharp Disposition, spring sheets, steel, nylon thread, 2023; Exhibition detail, WAF Galerie, Vienna, 2023, Photo: Kunst-dokumentationen, 2023

Bianca Phos & Yorgos Stamkopoulos, Touch me, don’t touch me, Zeller van Almsick, Vienna, 2023, Photo: Kunst-dokumentationen 2023

Interview: Marieluise Röttger

Photos: Christoph Liebentritt