Caitlin Lonegan is an American artist working out of LA. Her abstract paintings illustrate her observations about light, movement, space and time. Every brushstroke is positioned carefully, having been thought out in earlier drawings. These are stand-alone works, too, and are being developed along with the paintings. During her working process, Lonegan uses a whole range of colors, including metallic pigments, to create pictures whose surfaces change along with the different positions the viewer might take.

How did you get into painting?

I had a couple of revelatory moments in College. I did my undergraduate at Yale University in Connecticut, where I studied Applied Physics and Art. During an assignment about local colors, I took a picture of a Cézanne still life I loved and decided to focus on his brushstrokes. I expanded each of his brushstrokes so that they were the same size to fill up a grid. As I was doing it, the structure and depth of that image came to life – it blew my mind.

You were studying in the Physics department at the time?

I was studying Engineering, and I wanted to understand light and color. I was so excited about what was happening with the Cézanne brushstrokes, just so smitten with color and what it did. And this has been my subject ever since.

But you were talking about several revelatory moments?

Another moment was even more color focused. We were painting in a fire engine red but putting it next to a bright fuchsia in a painting, it looked like a pale pink – I was amazed! At the time, I was stretched thin because I was doing this double major in Applied Physics and Art, but the more art I did, the more I wanted to do.

Why was that?

Well, I started to realize how painting was a means of communication with other people. And that thought solidified the direction I wanted to take; I wanted to make it my vocation.

You combined Physics and Art in College: what do they have in common?

I think there is a connection. It is a commitment to study specific things in depth over a long time, and if you look back at bygone eras, the artists were the scientists. I think it’s changed now, but we would definitely need more communication between the disciplines. Science is good at asking specific questions, and art is better at figuring out questions that can’t really be narrowed down. Einstein for instance was somebody who was wildly creative in his discoveries. And he even had a walking practice to stimulate his thinking! He wanted to give himself room to have leaps of imagination.

From Einstein’s working process to yours – what is it like?

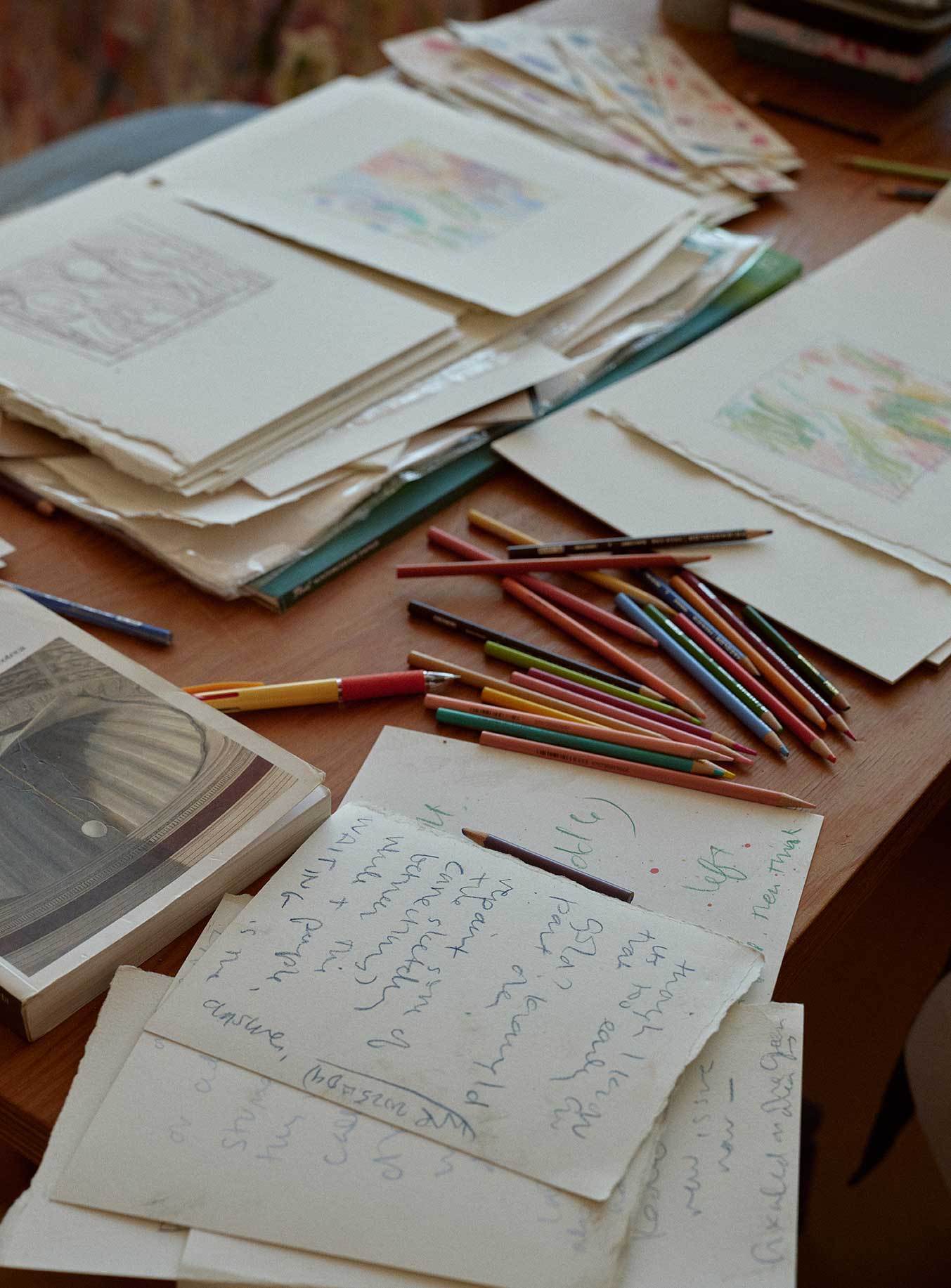

There is a first stage in which I take a lot of notes, I draw a lot, I gather lots of different kinds of materials and surfaces on different scales. I know I want to work on something when to me it seems like a puzzle that I can’t figure out! Like some sort of phenomena that I am thinking about and don’t quite understand yet, but can’t let go of.

Is that the physicist in you?

Yes, but it's also me unearthing a memory. I don’t know what it is when I get started, but the physics part of me goes: I am going to put a visual form of the memory down in different iterations, on different surfaces, and draw it, study it, until I locate it and understand what the memory is.

Almost like an experiment in a laboratory!

Yes. I figure out the palette I’m interested in, the motives, the shapes, and get an idea about a place or memory. From there, I can contextualize those bits of memories, those glimmers into a place and a context. That is the layering of the meaning.

Do you draw or do you get to the canvas right away?

Both. I go to the canvas with some ideas. But because oil painting takes a long time to dry, and I am interested in color, I will keep looking at it but at the same time draw throughout the process. I will put a painting down and let it dry, put another one on the wall… I work on a few paintings at the same time, moving them around the studio. I paint with the painting flat on the ground and draw from it when I look at it hanging on the wall.

So it’s back and forth between painting and drawing?

Yes, until I feel there is enough material. I want to first capture the memory I was thinking about, but at the same time capture the process of what happens in the studio.

What kind of paints do you use?

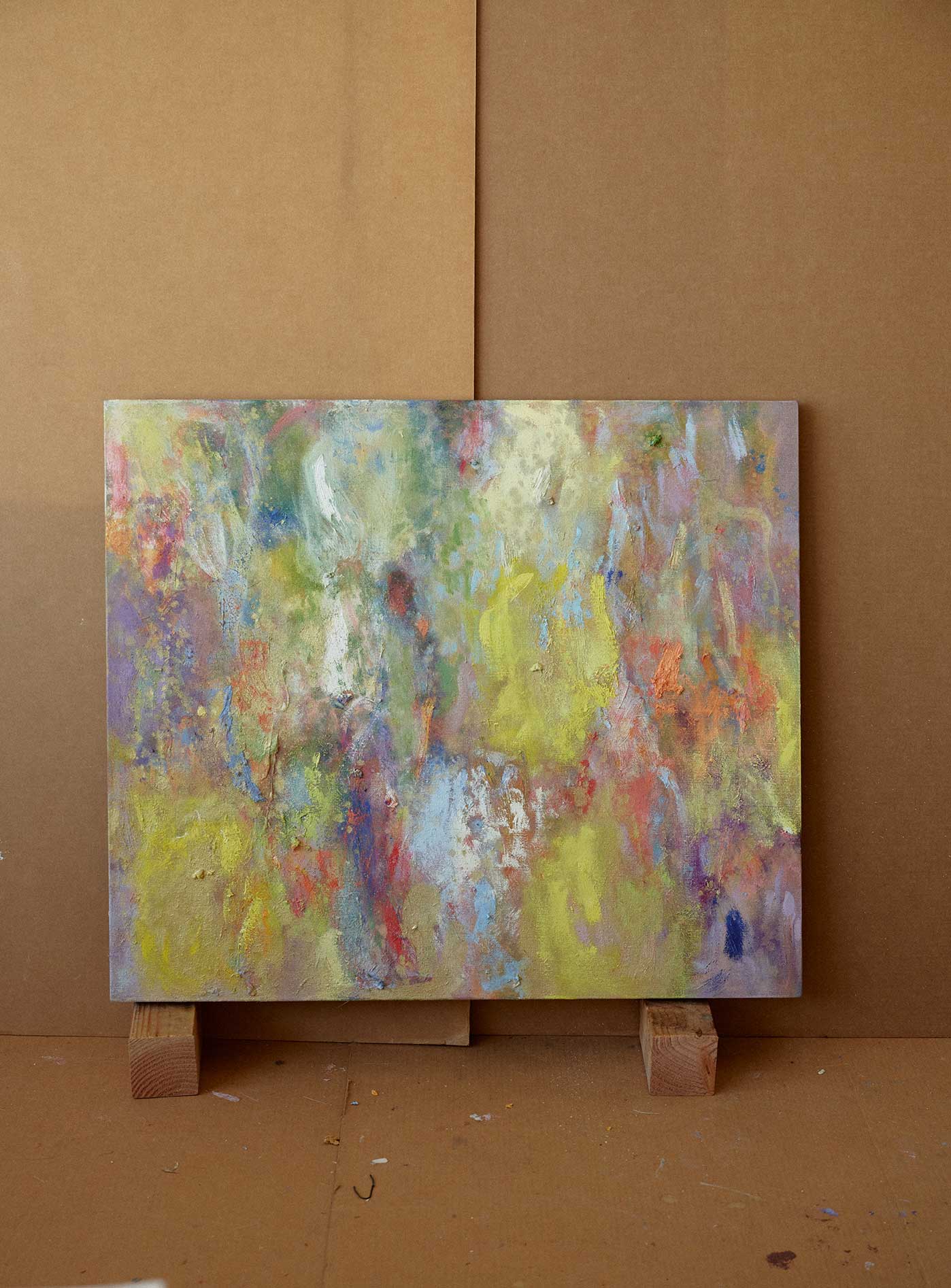

It’s oil paint in a range of colors. Actually, science influenced me, because I got very excited about the potential surfaces that oil paint could make. I thin the paint down with mineral spirits or linseed oil, I stretch it, so that there are moments when, on the paintings, it looks like velvet, or lush and optically engaging… I like to have a full range of surface.

I read that photos don’t do your work justice – is that true?

I explicitly make the paintings to be experienced in real life! I think that even a good photo is just a reproduction of one view in one context. Intentionally, my paintings’ parts look different, some come forward, others recede. And as you move around the work, you have these moments of discovery that for me are what the painting is about.

Because your work is never flat?

It’s never flat. Think about the way light works: it bounces directly off at a right angle. If you move around a painting in different ways, you will be seeing different parts of the surface. This is true of any painting, but I have exploited it. Different moments of light come forward. It’s a bit like making an incremental hologram (laughs); that is the aspect I am looking for.

Is that your contribution to the history of painting in a way?

I think so. I know that when a painting is leaving the studio, it will be viewed in different contexts. Obviously, I won’t be able to control the lighting; it might be in a dim hallway or next to a window, or in a museum. And I actually embrace the variability of what the painting will look like in each of those contexts.

You paint group of works at a time. Do they carry a message?

Yes, I think that there are some things that carry from body of work to body of work. My interest in color, light and context has continued. But my palette has shifted. It was incremental, but ten years ago I used mostly dark, sober colors, and now it’s the full spectrum! I am still understanding the language myself, but there is a kind of dynamic that plays out in one body of work to another.

Always underpinned by a certain narrative, right?

Yes, there is definitely a set of interests. And if somebody is a follower of my work, they might see what I do.

When do you know a painting is done? Does the picture tell you that?

(Laughs.) Well yes. There are some fact-based parts though! I want the picture to capture some aspects of change. I want it to share some of the discoveries I may have had while I was painting. I want the painting to have matter in it. And then there are a bunch of technical things that I have to do to make sure that happens!

You said: “I am finished when the surface feels uncanny and the image reads quickly”. But somehow I don’t think your paintings are to be seen “quickly”?

You can see them quickly, but you could not really take them in. It’s relative. I have to compose the image so that it is possible for there to be some Gestalt to it. If it doesn’t reach that point, it’s just a bunch of marks on canvas (laughs).

Which means: if you don’t have a motive, thought or narrative behind this bunch of marks, it is just that. And that is where art comes in, right?

Yes.

Talking about narrative – you’re a keen reader. You even dedicated a book to Dorothea Causabon, a character in George Elliot’s Middlemarch…

I loved her, identified with her. I was excited about how Elliot's characters come to life so much. This is a great ideal for any artist: to create an environment that is fully activated and comes to life. And Middlemarch inspired me in so many ways.

Would you say that you bring your paintings to life?

I hope so, that is the ideal.

Would you even describe your paintings as characters?

That was part of what I was doing at the time I did the Dorothea book. I was thinking about different ways of painting and how they can add to life. You can make a painting that is really quiet and accompanies you in a simple way. And you can make paintings that are really overtly joyous, exuberant, or loud and provocative. I was trying to make paintings that operated according to these cadences, as distinct characters.

I need to ask now – what do you think a painting could add to life?

(Laughs.) Well, that is the question behind every painting, and each of my paintings is sort of an answer to that. I don’t think I have words for that one.

You probably have a brush for that one!

Yes!

Is there any other book or objects that inspire you?

I saw a few things that impacted my work: for instance, Piero Della Francesca’s “Brera Madonna” at the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan. Before seeing it, I already had increased the colors I was using in my paintings and was thinking about tension in artwork. And then I came across this painting! The protagonists are interacting in a way that you can tell is emotional, and the light is a cool light, made from light yellows and blues. The painting really captures this thesis of vision, while having this heat of narrative at the same time.

You make me want to see it!

It’s really powerful! I first saw it in 2022 and have been thinking about it ever since. The notion of cool light and heat is important to my work. And then I went into a deep dive of the impressionists and post impressionists again…

Back to Paris, then!

Yes. Monet’s Water Lilies, and the way he aggressively paints in his late paintings, fascinates me. He has no regard for the surface.

You mean his monumental Water Lilies at the Orangerie Museum?

Yes, that’s what I am talking about. I’m intrigued how Monet painted some parts of the water vertically, and the flowers or clouds horizontally, in a way none of my contemporaries would do. Part of me is trying to do things like that; I have been interested in directionality.

You wrote about the difference of seeing Monet’s famous works in person, while at the same time being so familiar with them through photos…

It is a long-standing concern of mine. What are these surfaces that we feel, that we grapple with? And recently I got excited about Seurat. He was really influenced by classical painting, dealing with vision, with stasis and movement at the same time.

You are talking about surfaces that we feel, that we can’t forget…

And what happens when we really see them! I recently read a book by Sebastian Smee about how impressionists came about after the Siege of Paris in 1870, when the city was attacked by German forces. Meaning that the images we see as idyllic today often come from challenging moments.

Which probably is an expression fit to describe the US right now?

Yes. Reading the book felt prescient. And I think people turn to landscapes and to art in times of stress.

I recently heard that artists make safer art in times of crisis. Do you agree?

It’s a complicated dynamic. There is a temptation for gallerists to think that they can get support for work they think is safe. But I don’t agree. In hard times, the art I am interested in comes from a place that might be faced with structural challenges, with lacking funds… We might have to work smaller but it does not have to be safe. There can be beauty and urgency and power in working with what’s on hand. Limitations can be incredible boosters, creating incredible and powerful art.

What are your new projects?

I have a spring show “Gems and Roses” in New York with Broadway Gallery until the end of May, and after that, a drawing show with Galerie nächst St. Stephan Rosemarie Schwarzwälder in Vienna. And I am working on a book with artist Carmen Argote.

Caitlin Lonegan, Untitled (G.Y.R.B.V., gest, field, grid, F-B, can, 2025.04), 2025, oil, metallic oil on canvas, 48 x 48 x 1 1/2 inches, Artwork © Caitlin Lonegan, Courtesy Caitlin Lonegan and Broadway Gallery. Photography: Jeff Mclane

Caitlin Lonegan, Untitled (O.G.B.G.R.Y., Seur, Mo, F-B, lin, 2025.03), 2025, oil, metallic oil on linen, 28 x 32 x 1 1/2 inches. Artwork © Caitlin Lonegan, Courtesy Caitlin Lonegan and Broadway Gallery. Photography: Jeff Mclane

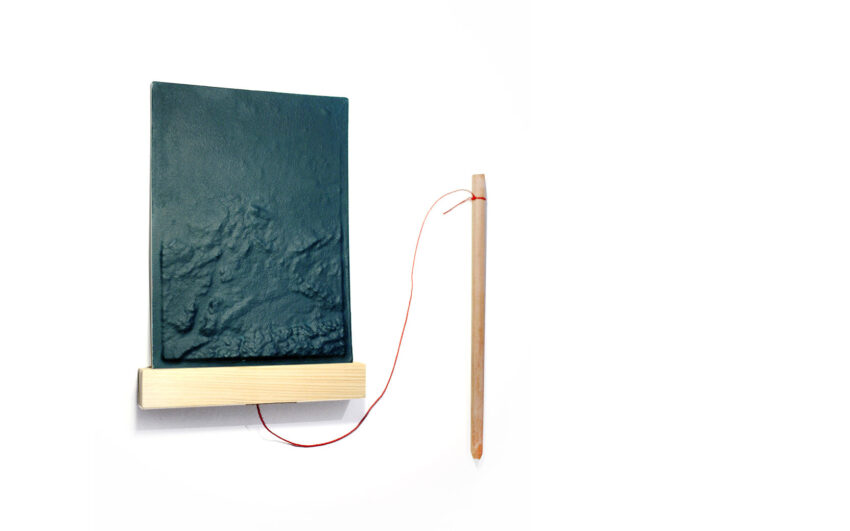

Installation View, hot, clear, scratchy, soft, 2022, Galerie Naechst St Stephan Rosemarie Schwarzwaelder, Vienna. Artworks © Caitlin Lonegan, Courtesy Caitlin Lonegan and Galerie Naechst St Stephan Rosemarie Schwarzwaelder. Photography: Markus Wörgötter

Installation View, hot, clear, scratchy, soft, 2022, Galerie Naechst St Stephan Rosemarie Schwarzwaelder, Vienna. Artworks © Caitlin Lonegan, Courtesy Caitlin Lonegan and Galerie Naechst St Stephan Rosemarie Schwarzwaelder. Photography: Markus Wörgötter

Interview: Alexandra Markl

Photos: Cody James