Carsten Fock, known for his expressive paintings, installations, and felt tip pen drawings, is one of Germany’s most successful contemporary artists. In his drawings and paintings, he combines the media of text and image, mixing motifs from the 19thcentury with visual worlds from today’s pop and popular culture. After fleeing from the former GDR to the Federal Republic in 1988, he studied art and became one of Per Kirkeby’s principal master students at the Städelschule in Frankfurt/Main. Today Carsten Fock lives and works in Bamberg, Copenhagen, and Vejby. In conversation with Collectors Agenda, he talks about his socialization in the former GDR, the search for his artistic medium, and the significance of felt tip pen for his work.

Carsten, what does art mean to you?

The answer is very personal. I had years in which I thought about quitting many times. I’m interested in the contemporaneity of art. Art is the intellectual confrontation with myself. I find the crazy art market that has emerged in the last ten years alienating. Artists should uphold the ideals of art.

How did you come to art in your childhood?

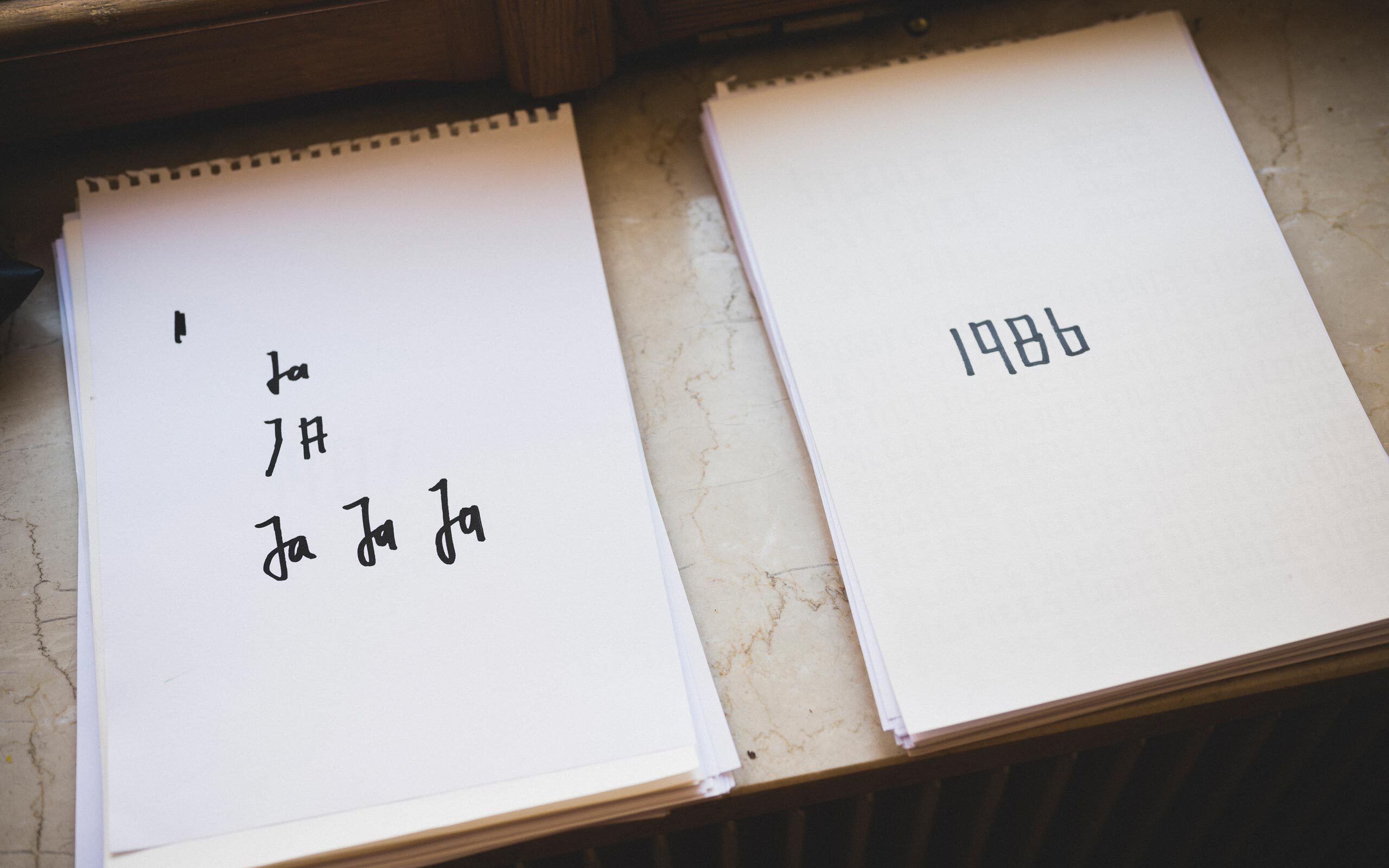

I grew up in Thuringia and fled in 1988, a year before the fall of the Wall. As a child in the former GDR, I just made things. I drew tanks with my grandfather, who was an officer. And there was a catechist in the village who instructed me in religion. I was the only student in the parish, because I grew up in the otherwise atheistic GDR. The afternoon care in the parish was a protected space. And that is where I picked up a few things. The typography that I still use today comes from rudiments I learned at that time. Because many things didn’t exist in the former GDR, my teacher was always coming up with something creative. She had only one Edding pen. And with this pen, she developed a very specific typography with which she handwrote all the posters. I found that aesthetically very impressive. And then there was the color purple. Everything was always purple in the church. That left its mark on me.

So your experiences in the former GDR influenced you in your work?

Most certainly, especially the prescribed narrative painting that existed in the former GDR for systemic reasons. I didn’t notice any art that deviated from this. Above all, I knew the ideological art world, which still produces a physical horror in me today. For a while later, I did this work with words and slogans myself.

What was that time like for you when the Wall came down?

Like many others at the time, I asked myself what I was doing now. I always wanted to be a soccer reporter because I wanted to travel. Then I started training as a foreign trade merchant and studied business administration. “Do something clever,” my grandfather always said. And I was in a photography course where the leader took me by the hand and showed me the book Goyaby Lion Feuchtwanger. That inspired me very much. From that point on, I started drawing again. Art became a factor for me to come forward in the world and express myself. I had briefly thought about studying in Berlin. But on one visit I realized that it wasn’t for me. Then I went to the Werkbund workshop and learned a lot about arts and crafts. There I was told that I had to study art. That was an exciting time. I didn’t want to go to Düsseldorf or Frankfurt. The art academies there were a bit too big and too elitist for me. So I examined the academy in Kassel. There I met the Fluxus artist Alison Knowles. She questioned my painting, and I developed further as a result. But at some point Kassel was over. I worked night shifts at the VW plant and painted afterwards. Georg Bussmann encouraged me to move on. Then I finally went to Frankfurt to study at the Städelschule with Kirkeby.

Who was the most inspiring person for you in the academies?

Interestingly enough not Kirkeby! The Munich art scene was inspiring – Amelie von Wulffen, whom I hold in very high regard, and Jochen Klein, Wolfgang Tillmans’ friend at the time. At the Städelschule, painting was completely frowned upon. With Bayrle, everyone was just constructing. And I arrived there and asked myself what I should do now. Christa Näher was important for me. At that time, I started doing conceptual work on the allotment garden, for example. She asked me, “What are you actually interested in?” That’s when I came back to drawing and started making monochrome works. I stood out with one. I just filled in a studio wall with Edding pens. I was really looking for what occupied me, and I had interesting encounters with a Finnish exchange student who introduced me to the Outsider art of Adolf Wölfli.

And Kirkeby?

Kirkeby hardly sought out conversation with me at first. Later I found out why that was. His silence also left its mark on me. We were very few students, but hardly anyone communicated. It was really disquieting. I went out a lot. I always had to go out on the street. There was this insane belief in progress in painting. And there was such an incredibly burdensome pressure to innovate at art school. The street helped me deal with that.

Which exhibitions have shaped or changed your work?

An important exhibition for me was a show with Oliver Körner von Gustorf at the September Gallery in Berlin. That was a double exhibition called The Devil and the White Kings. Looking back, that had an enormous range of things that engaged me. Kosmos der Angst (Cosmos of Fear) at MMK Frankfurt was also important. Exhibitions that have been recently running in Leipzig with Jochen Hempel and entitled Die Würde und der Mut (Dignity and Courage) and Vejby. It included my installation BRD 88 with very beautiful graphic works.

Have you ever used media other than felt tip pen and brush?

Yes, in the Werkbund I made sculptures, especially portraits. And the director of my workshop commented: too two-dimensional, try painting. But I also like to work in space. In the show Vertrautes Terrain (Familiar Terrain) at the ZKM Karlsruhe, for example, I designed a room entirely in black. However, sculpture is not really my area of expertise.

Where do you find the most inspiration?

By the sea. There I usually draw before the first coffee. Then I go meditating and jogging. Drawing is really like jogging for me. It sounds totally stupid, but it triggers this completely wanton thing in me. “You have to draw,” my body then tells me. There are moments when it feels just right. In Vejby in Denmark, where I also live, it always comes naturally.

What is the typical process when you paint pictures?

It is always different. There is a safe path. It involves me going into painting via the drawing. In other words, I don’t pre-sketch something, but experience the drawing itself as an energetic process. But the best thing is when I feel this pure freedom, leave the usual path and just get going. Sometimes this results in works that I find terrible. But that's also an interesting process. Right now I’m at a point where I’m looking at old things and thinking that something new could happen again. I got into the habit of using a felt tip pen at art school. I also painted a lot with oil in Kassel. But that was too laborious for me. And in Frankfurt I started painting with Japanese felt tip pens. At some point, the Sharpie came along. At first it was the normal standard Sharpie, later came the paint pens. Right now, however, I work a little with Edding markers.

What will the Bonn exhibition look like and what other projects do you have at the moment?

In the Bundeskunsthalle in Bonn there will be a cube-like room in the blue-violet that I have been using for twenty years and buy from my paint dealer in Berlin-Kreuzberg. Actually, I wanted to show my latest works from the Danish sea first. At the same time, I have an exhibition of works from Vejby at Galerie Jahn in Landshut. The exhibition is called Zum Meer. And there is also an exhibition planned in Munich with works by Kirkeby and myself. And finally, I would like something to happen in Denmark again.

Why Denmark?

The light by the sea is beautiful. For twenty years I worked only at night. But at some point I realized that the light is important for me not only physically, but also in painting.

Installation Bundeskunsthalle Bonn, Farbe als Programm, 2022, Courtesy the artist

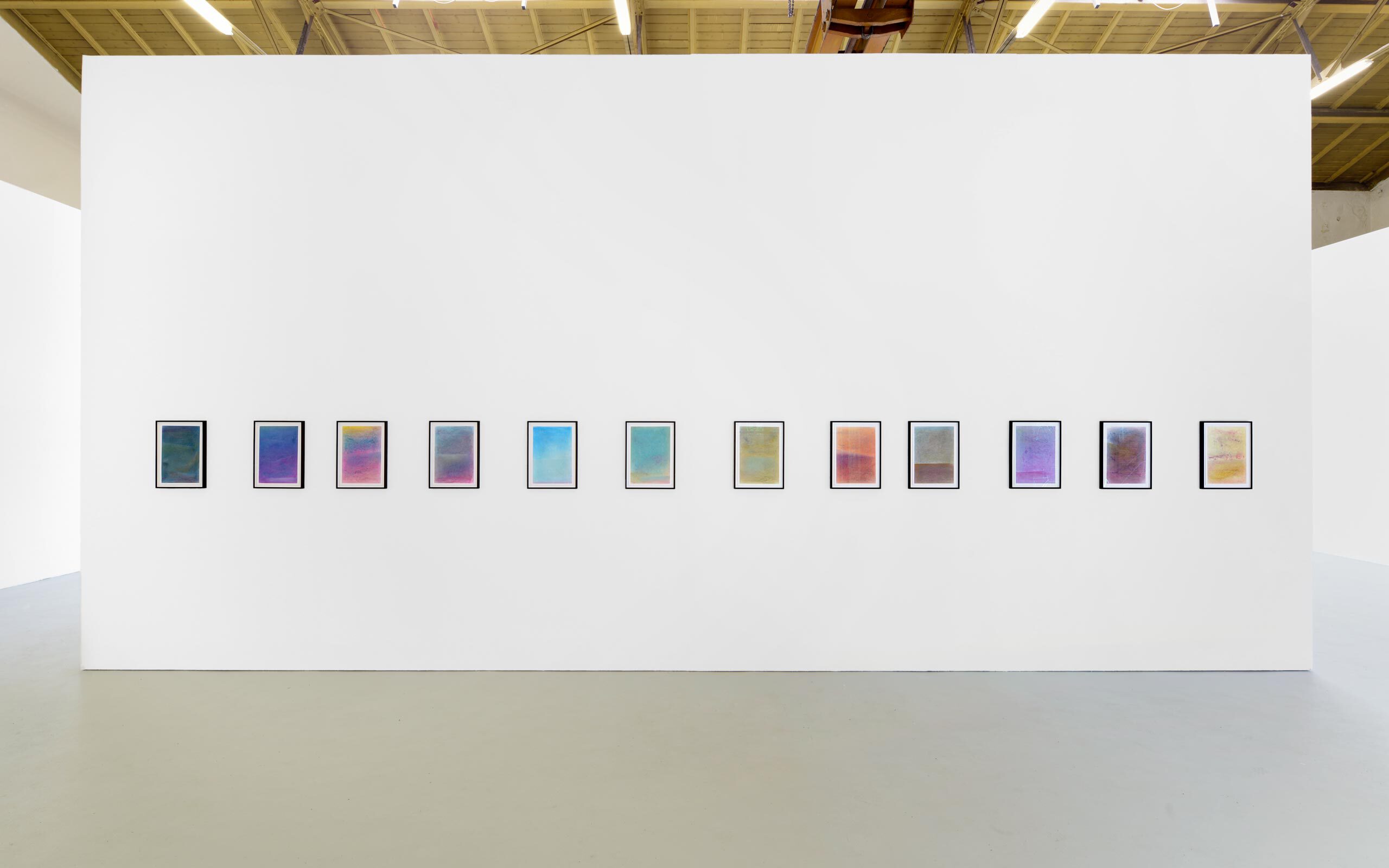

Exhibition view, Vejby, 2021, Jochen Hempel, Leipzig

Zum Meer, Galerie Wolfgang Jahn, Landshut, 2022,

Credits: Galerie Wolfgang Jahn and Carsten Fock, Photo: Harry Zdera

Monochromes, Die Würde und der Mut, 2012, Courtesy the artist

Interview: Kevin Hanscke

Photos: Maria Bayer