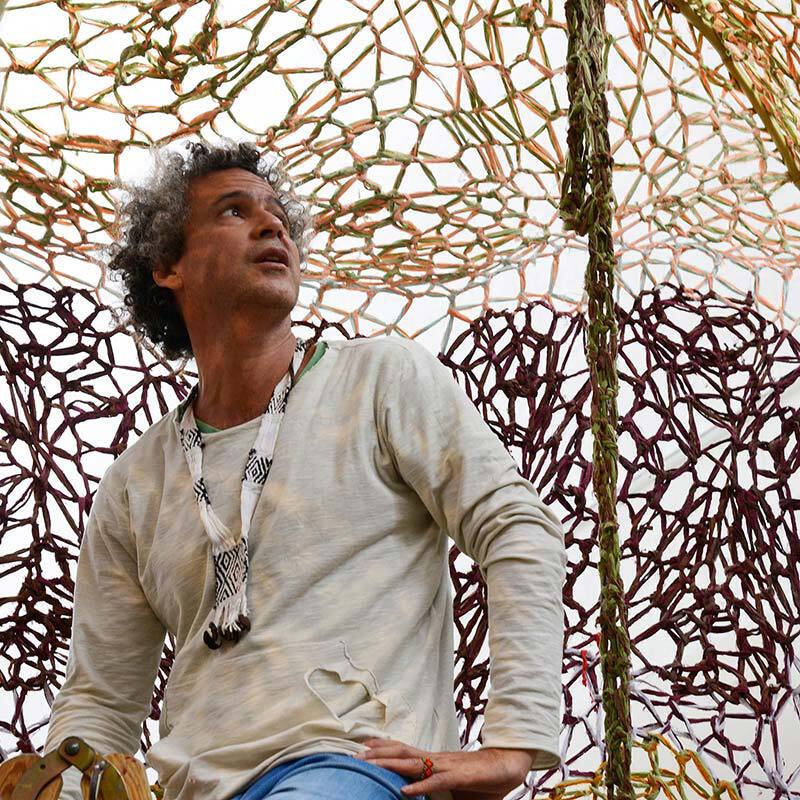

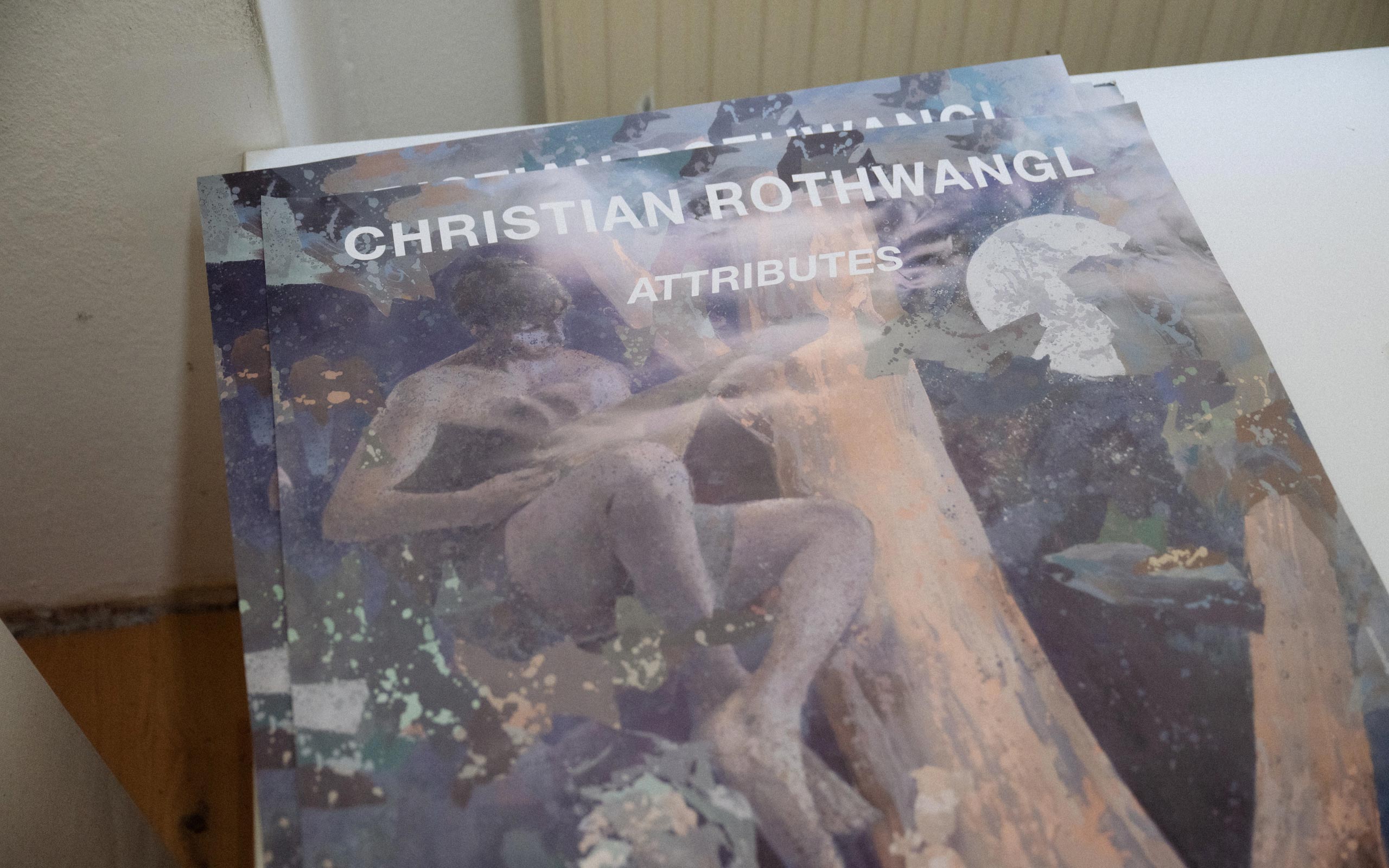

‘The brush must also think for itself.’, comments Christian Rothwangl on his work. However it is the artist himself who does most of the thinking: about technique and the status of pictures. His “washed-out” paintings have become his trademark, in which he weaves identity and mythological-like scenes together.

Christian, how did you get into art?

When I think back, I always see myself drawing. I grew up near Bruck an der Mur in Styria, and when I remember my childhood, I was always busy creating something, building something, or playing theatre with my sister. A more professional interest in art developed at high school, when I moved to a boarding school in Graz.

Was there any art in your home when you grew up?

Not much. And the notion of artist as a job per se did not exist. This is why I was interested first in becoming a priest, as the catholic stagings and church interiors were incredibly attractive to me. A mass has something of a performance, too, so I didn’t feel it was too big of a leap from wanting to be a priest to becoming a visual artist. Not having grown up in an intellectual, artistically literate environment led to a certain insecurity when I started out at the Academy though, and sometimes still does.

Even though you are being represented by a gallery now?

It might give you a sense of security, but as a painter, one is always under the suspicion of working rather commercially than intellectually. But the limits inherent to this medium, painting, hold a great freedom for me. An artist friend of mine remarked lately, while I was talking about a painting, that painters are something like a strange, secret society within the art bubble. I do like this microcosm with its own rules, in which you can create new pictorial worlds on a piece of paper.

Talking about a piece of paper: you did start out with drawings, right?

Yes. And I still draw a lot, my common thread is often what I do on paper.

Are these just sketches or can they stand alone, too?

Both. Paper is always nearby, and I can quickly jot something down. At the same time, I see it as something unique: painterly works on paper using ink. Painting, on the other hand, asks for a different approach. It would not make any sense for me to put my drawings on a canvas, just in a larger size.

How did you move from drawing to painting?

First, I had to translate from paper to canvas, and this took time: the material is totally different. You can work forever on a canvas; you have to stretch it, buy it, it’s expensive. This held me back at first. Then I realized: if I wanted to paint, I needed to think differently. I can build up pictures from the deep, but that I need time for. This was a problem for me, as I am not patient at all (laughs). But by now, it works out well.

Your earlier work is more abstract: did you also produce sketches for this kind of work?

Yes, I might have been even better prepared when I started an abstract painting. Narratives with characters form a space more quickly, and I can build it up. But with abstract, I need to make it instantly right. Today, I’m still starting paintings as abstracts, but I have a different approach than I did earlier. Through using figures, my work has become freer; I am looking to build shapes on the canvas

Where does this development come from?

I was always interested in both, the abstract and the figurative; today I am trying to merge the two. It is a slippery slope: it can turn out badly when I just take an abstract background and then put some figures in. If that becomes my standard procedure, it won’t work. Instead, I try to put figurative and abstract paintings side by side in my shows. From series to series, I try to find a new path. Both appeal to me; it's a contrast and I like its friction.

Is this also a way of documenting your own development?

Yes. I paint in series, so I put I several pictures next to each other, and it's exciting that I can find a different solution for each one, about what painting can be. Sometimes, it is determined by narrative, clearly legible scenes, and sometimes purely by surfaces and colour.

This sounds like a work in progress, like you are searching for something?

Absolutely. I am much more interested in developing new possibilities than in repeating safe choices. I don’t want to bore myself. I like to try out something that at first I thought might never work, but which keeps bugging me.

How does it feel then when a pictures works out?

It is a strange feeling. As soon as you get into the flow, the picture paints itself, it is an intrinsic logic that is hard to describe. Opposites that balance each other out. Often, I start with some color, which in turn makes a shape seem obvious… It’s difficult to describe.

How closely do you transfer your sketches onto canvas?

The sketches are around me while I work, and then during the painting I realise: Ah, now it’s about what I have already worked on with that sketch. You always follow different ideas.

Do you think that your paintings tell stories?

Sometimes more, sometimes less. Through all my series, there are two stories. One deals with content, which I find less important. The second is about different approaches, like its own little history of painting.

Which materials do you use?

Ink: it’s a watery material which dries quickly. And now I also use acrylic. The surface, the washing out, the compacting, that everything is one piece – all that has become a technique.

Which lends your paintings a high recognition value…

Yes, I wash out. I paint on the floor, pass wet ink over it, let it half dry. What is then dry remains, what is wet is washed out with the substrate. This is how you can see the layers underneath. I like it, because it implies that while working, you have to think onwards and backwards at the same time. It’s basically a trick to make the work more difficult (laughs). Because you never know exactly how the material is going to react – and I like this bit of serendipity.

Does this have to do with the fact that you don’t want to bore yourself?

Right. My figures seem almost meaty, the painting is being formed - but still, those figures stay completely flat thanks to the washing out, because everything superfluous is being washed away. I don’t like thick painting, my way of painting is almost bodiless.

You started out with grey, and black and white paintings…

When I arrived at the point where I switched from paper to canvas, it made sense to use color. It has a different materiality; on paper, color wasn’t as important. But the switch to canvas…

Is it such a big step?

Yes! At home in my bedroom, I built in a loft bed to create more storage space for my pictures – it’s work that I have never shown anybody, because I wasn’t yet happy with it. I just had to paint so much! 30, 40, 50 pictures, which I never exhibited. But I guess it has to be that way. It was just surprising how different the work on canvas turned out to be.

Today, you have found your style though?

If you want to call it that. Because the surfaces of my pictures have a certain recognition value, you can identify even those as mine who have a different methodical or programmatic approach. My work from a couple of years ago was more abstract, and I kept painting different formations of colorful “stones”. These are abstract shapes, which for me tie together the figurative and the abstract. I also wanted to think about the space in a picture. In a painting, you can decide whether the stones fly around in space, or whether there is a gravity which holds their formations together.

What are you inspired by?

I am looking at a lot of art, older art. Bonnard I have rediscovered. In general, I am interested in approaches that reflect on painting as a medium and deal with it in a playful way, concentrating less on the content or inventing stories. For instance, at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, I looked for a long time at a Rubens painting - but in the end, I had no idea about what happened in the painting. Because I see these bodies in it as just some scaffolding for the painting. As some carriers for emotions that do not need any content. I am interested in shapes.

Is this also true for your own work? That the viewer does not have to know about your story?

Right. But it’s fun what people sometimes read into the pictures. But that’s ok, of course.

Do you actually have a personal relationship with your models?

Yes; it happens that when I am throwing a party in my ground floor studio, people stop by the open windows. We start talking, I ask them in and end up drawing them.

Drawings that you will then use in your paintings?

Yes. You could almost call it performative! People party, and I draw. I like doing that just next to them.

Is your art about identity?

Yes, it is, too. Often, gay men are attending my parties. And then I ask myself – what do I want to tell in a work, what do I leave out, what is important?

Art about identity is everywhere these days…

I know, and it’s great, but that’s not why I am doing it. I am rather somebody who likes to hide behind his pictures. That’s why it’s so hard for me to talk about it! On the other hand, it is also an act of freeing myself from my youth, in which I, as a young gay man living in the countryside, felt somehow repressed. I came out when I was 19; this first half of my life, in which I had to fake it, comes through in my work.

Is that the case too for some of the people who attend your parties?

Once, somebody in drag came by the window, and we started talking - she came from the countryside, same as me. I asked her whether I could make a drawing of her. At first, she felt uncomfortable, but I drew her likeness for quite some time, looking at her all the time. And she came to life and had a really good time.

Because you offered her a view that she was not used to?

Yes.

Are you also looking for that unencumbered view - the same you have on your models - for yourself?

True.

Do you ever happen to be in a painting yourself?

That’s more by chance. An auto portrait does not automatically mean self-revelation to me, it could be through another figure, too. My figures are neutral when I paint them; it rather amuses me when I recognize myself in them. But it’s of no consequence whether it is me or anybody else. Every picture means I am giving away something of myself.

Isn’t there any art on your walls?

No, I would find that really uncomfortable, because I do know how personal these paintings are. It is art, and not something that I would put on the wall as décor.

In your work, you repeatedly deal with mythology…

Sometimes I use figures that seem to have a mythological background. For me, these are motifs that suggest something universal. They don’t tell real mythological stories, but rather a habitus of mythological representation.

Consequently, these are stories that the viewer intrinsically knows about?

Exactly. This transforms my work into the sort of image that transcends a personal narrative to a universal one. Here too, I am looking for contrast: In a show, I might put a picture that tells a more personal story next to one that tells a more universal one.

Does this iconographic aspect also come from the fact that you used to spend a lot of time within the church?

Sure. These pictures are on my mind. And the idea of images on top of images. In churches, the main altarpiece can be framed by images that emphasize it. This harks back to an idea by Victor I. Stoichitã: the self-confident image. That was very important to me as a consideration: the status that images can have, how they out themselves as images. It's probably also a bit about outing.

So, do the pictures in your work groups have ranks?

Rather the same rank. But they play with the idea that they represent a picture of a picture.

So on a meta-level, you thematize the image itself?

Yes, absolutely. In my groups of drawings, you can perhaps see the different ranks more clearly, in paintings less so. One could still open Pandora's box, build installations... That would be a first step. If you want to give pictures different rankings, you would have to go further. But I'm still limiting myself at the moment.

You consistently think your work through - is that also the task of a young artist?

Yes. Actually, everything is only ever created in the making. Thinking about it happens separately from the creative process. I tend to reflect afterwards. It's often difficult when you have an idea and illustrate it... The brush also has to think for itself (laughs).

How do you feel about living and working in Vienna?

I have been in Vienna since 2013 and I really like it. However, I do need silence and quiet to be able to work, and I need to be alone. When I was at residencies, I had a hard time working if somebody was busy nearby.

Because you had the feeling that somebody else was thinking in the next room?

Yes (laughs). If I know that my mother is thinking about me, it feels as if she was sitting on my shoulder. I can’t bear it when I get the feeling somebody is thinking about what I am doing. I need total physical freedom when I work.

What are your new projects?

I am part of a show at gallery Krinzinger, and they will also show my work at the Stage Bregenz fair. My last show was large in size, and I had to paint everything from scratch. I need some time to breathe now, to try out something new.

Interview: Alexandra Markl

Photos: Christoph Liebentritt