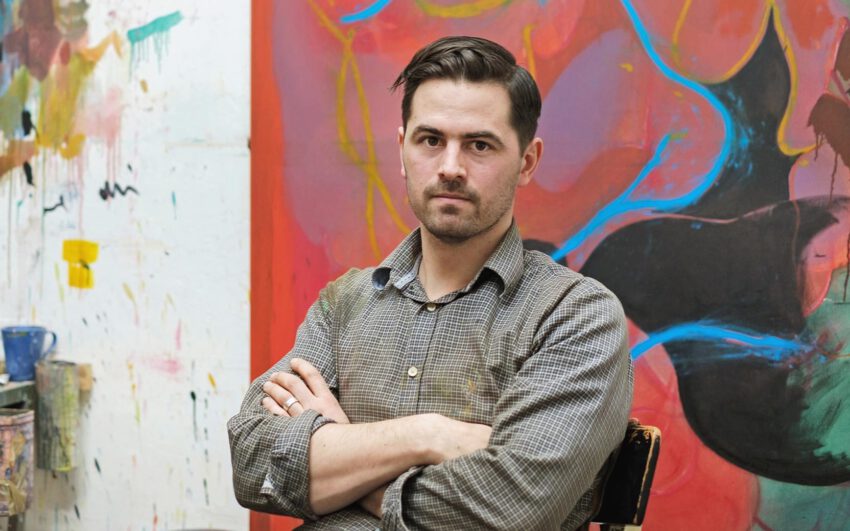

Clemens Krauss is particularly well-known for his pastose paintings from an unusually slanted angle, as well as for his controversial video works. The works of the artist, who was born in Graz and now lives and works in Berlin, examine in depth what truly defines human identity. With a surgical and curious look, he enquires into larger contexts, whereby he addresses relevant social, political, and autobiographical issues. It is not by accident that, prior to his art studies at the Berlin University of the Arts, Clemens Krauss also completed his training as a medical doctor and sometime later as a psychoanalyst, because, in his oeuvre, painting and performance, sculpture, psychoanalysis and video fuse together. At only thirty-six years of age, Krauss can already look back on innumerable institutional solo and group exhibitions on all continents, which gives him a rank among the most renowned Austrian artists of his generation.

Clemens, can you explain in a few words what your art is about?

I combine material, space, and even my (own) body with social and political observations and with the intention of producing works that evoke something, that stimulate.

What personal concerns form the basis of your artistic work?

My work is characterized by the fundamental intention of each artistic creation to critically examine the elements that define our world. If I simply reproduce certain things without reflecting on them, I repudiate this. Artistic interests offer infinite possibilities of critical examination, including exaggeration, aesthetics, and humor. Only reflected repetition leads to the production of knowledge or the acknowledgment of even unpleasant aspects. It can be compared to a physical digestion and growth process and applies to both the individual and society as a whole.

Among other topics you always concern yourself with individuals and society, is that correct?

I am very interested in the role of the individual in our society from an analytical point of view and I want to find out what it is that establishes the social order, beginning with the individual, the individual (human) body, and ultimately with several bodies in interaction, that is society as such, and to ask the questions: Who are the observers and who are the observed? Who are the actors and who is the audience? And what degree of freedom does the individual have in the society we are talking about?

Speaking about scope, for your work “Elternhaus” (Parental Home), in 2010 you inserted a 25 meter long endoscope through the ceilings of your parents’ home. The resulting video shows vertical views of four rooms sequentially. That sounds pretty radical.

This work is concerned with the organic treatment of a very personal location, in this case the house of my parents in Graz in which I grew up. This “intervention” was quite radical: Together with a woman architect, a craftsman, and a team colleague we determined the places where we could drill through the ceilings and floors which were in part up to 50cm thick. From my former playroom as a child on the top floor of the building an endoscope camera was directed through the rooms its progress observed on a monitor.

In what condition did you leave the house after this crass intervention?

It took an entire weekend until the perfect take had been achieved. The video consists of only one uncut camera tracking shot. When we had finished the craftsman returned on Sunday, and charging Sunday rates he lathed and plastered the holes, reinstated the wood paneling in the upper stories, and professionally concealed everything. We felt like the secret service bugging activity. When my brother who lives with his family in the house today returned after the weekend, the house appeared just as he left it. Of course he had been informed about the project before.

So he didn’t have a reason to get upset?

No, not at all! (laughs) However, it was an enormous intervention!

Where does interaction actually begin for you?

Interaction begins with myself, with the object and with the viewer. Seen this way, a micro image of society is created. Ideally, social connections become inferred and perhaps even comprehensible. These things are interesting to me and I consider them important particularly in times of such contradictory political processes. It concerns us all and we ought to continuously ask questions like: Where do I stand, where do we stand as a society? Where is something critically negotiated and processed? What is only being produced and neurotically repeated?

You are known for your structurally strong oil paintings that represent human bodies seen obliquely from above looking like their own shadows. Can you say something about their origination?

I have lived for long periods in London and São Paulo. In both places I had the experience of being under constant surveillance. One is aware of the monitors in public spaces on which one can see oneself and others from strange angles. Through this change of perspective in both the real and the symbolic sense the body becomes on the one hand more complete, the viewer on the other hand is being brought into a bottomless situation. All this occurs through a mere reduction of materials. From this observation originated my motifs of the “plan views”.

Through the chosen perspective the represented persons seem to lose individual personality. Is this intended?

I am concerned with the prototypical individual. In my representation – at least I maintain this – it is sexless, has no identity and is ageless. And it is not at all myself. Although I model occasionally for my own paintings, it has nothing to do with self-portraiture in the classic sense.

So you function more as a kind of deputy?

Yes, that is the right term! However, it is certainly different with the skin works. In those I serve quite obviously as the model.

Your work “Self-portrait as a Child” shows you at the age of approximately thirteen and it evokes strong reactions. On this year’s ARCO in Madrid your work was the probably most photographed artwork. How did you get the idea to portray yourself in a skin casing as a young teenager?

The teenage years are among the most sensitive phases in the life of each human being. Each viewer can identify with this child. At that age, I began to deal more intensively and more seriously with art and about that time I made my first videos. I still work with the material of these videos. The Self-portrait as a Child is both autobiographical and a reference to my own artistic practice.

“Self-portrait as a Child” has been presented in various places. It is interesting that it has been laid out differently each time. Was that the intention?

There are an infinite number of possible ways to lay out and present this sculpture. There is also a basic instruction guide for others to lay it out. In principle the presentation is centered on the moment of the extended body surface “being thrown down.” It is a very anti-heroic and also quite unprotected gesture!

Does the body “posture” and the interaction of the two halves of the body mean something different each time?

In the exhibition Kunst und Scham (Art and Shame) at Museum Marta Herford 2017 my intention in the positioning of the body was very clear. The theme of shame is very present in early adolescence. It is a vulnerable age in which one struggles with becoming oneself and with change. It is an enormously conflict ridden time as childhood and youth must be understood as in conflict. Therefore this special age interested me very much, also with regards to the videos that I made at the time. These are by nature very playful and in a certain way were quite immature. Twenty years later I make works from them that are presented in a professional, artistic context. Here a cycle is completing somewhat.

You’re talking about your video works for which you produce new works from old video footage.

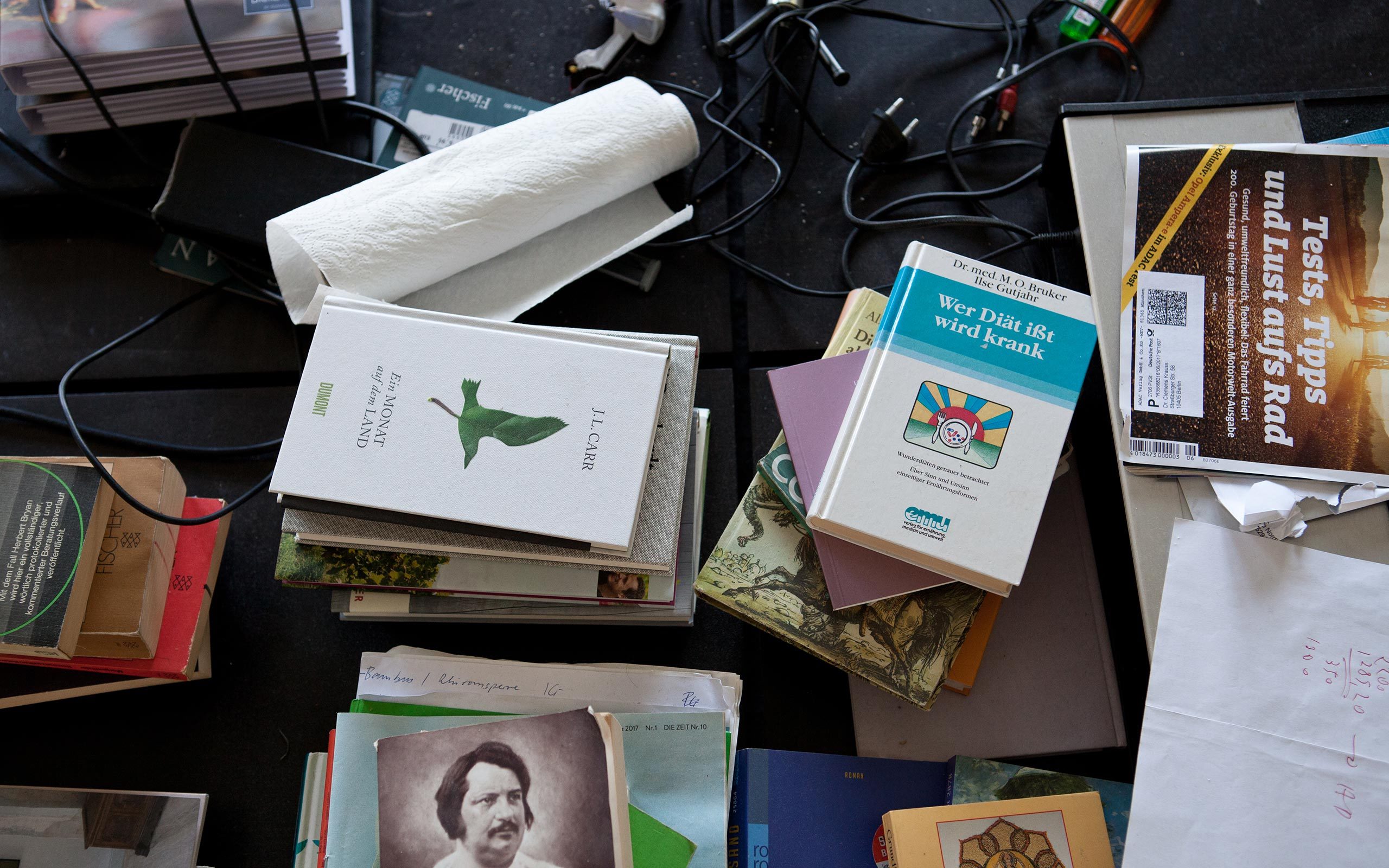

From the material produced in my childhood and early youth series of film collages are produced today. These videos receive a current social or political reference in retrospect through cutting and post-processing. A soundtrack with computer-generated voice of a child or youth, for example, reports biographical events in the third person – absurd, bizarre, and fictitious. In the process no new narratives emerge but rather chains of associations that can form other storylines.

The scenes shown don’t follow a chronology?

No, there is no time-related or direct text-related reference to my own biography. They are merely fictional stories with no relation to reality. At the same time, the unknown doesn’t recognize negation – being the unthought known as it were, it can achieve a more general validity.

The narrative voice, however, seems to work restlessly against the images. Ceaselessly it strings together all forms of pathological behavior, which in the context of the images allow the viewer to draw bizarre conclusions. As a viewer one can hardly follow, is this intended?

Yes, the dynamic is intended. The works are short and repetitive, so that one can quickly enter or leave – or watch them several times consecutively.

With your videos, do you work through something from your youth that concerns you personally? Or how can this intensive involvement with your former self and its actions be explained?

Looking back, a gap opens. Everyone has this gap. Looking into it, must not always be pleasant. However, I think it is necessary for it serves one’s development. In my case, I discovered playfulness in those video experiments. At the time, I was twelve, thirteen, fourteen and I had time, I played around a lot and simply filmed with no specific conscious goal. At that age one does not articulate so well. To look at myself at that age today, and observe my immature gestures and facial expressions, it is amusing. Some people are very touched by the videos, perhaps because they find something of themselves in the child.

Let’s stay with the analytical aspect of your work – besides origin and childhood you are obviously also interested in the concrete work of direct confrontation with the viewer. You offer sessions regularly in separate areas of your exhibitions. What does it mean in practical terms?

With the goal of expanding my artistic repertoire, I went through psychoanalytic training and I’m allowed to work also as an analyst. Furthermore, I regard it as my responsibility as an artist to make social interventions. Whether in my work I reach the masses, or what we artists call the “art audience” is always unclear and will probably remain that way.

Can you explain a little more precisely what the technique of analysis means for your artistic practice and how this knowledge can be useful?

I have internalized the theory of analysis for me personally and for the rest of my work. Psychoanalysis or psychotherapy as treatment is verifiably effective. At the same time, the theoretical knowledge is a very useful means to explain the world – an access enabling me to describe the world. This is reflected more than ever in my work. For me it was like learning a new technique, a new form of artistic technique as it were.

Are you conducting real psychoanalytical sessions as part of your exhibitions?

In a space that is separated from the rest of the exhibition space I receive visitors for anonymous solo sessions by appointment. The conversations are not documented in images and sound and the session lasts exactly 50 minutes, like a regular analysis session. The visitor can confront me with his questions and concerns and I do my work as an analyst.

Surely, many visitors would feel reticent, when they are all of a sudden asked to step out of the passive role of an observer into a very personal interaction.

As a rule, the resonance is very good. There were days during which I received visitors without interruption throughout the entire time the exhibition was open. That is very exhausting for me as well, but also very instructive and full of discoveries. There is also the possibility to attend several sessions consecutively. As I said before, I profit, too. It must be understood as a bidirectional phenomenon and is eventually also an artistic activity that develops between two people. During this time, an additional viewer would see the closed door bearing the notice, “please don’t disturb.”

What essentially is such a session about?

This kind of work is a form of intervention, which ideally evokes something, which is triggering something in both the viewer and myself and at best results in insight. It is very important to me not to moralize, I don’t want that in any of my works, neither do I want to be didactic or pedagogic.

So you are constantly learning while you work on an artwork.

I would like to replace the word “learning” with the word “recognize.” Ultimately, art is an offer to people to recognize something and to see something about themselves.

Do you document your new findings from the psychoanalytical sessions? Or is it for you as an artist only about this moment?

I don’t document the findings. Nothing is recorded in any form whatsoever. That is important. But the impressions from the sessions do have an impact on me and indirectly this impact can be found in one work or the other.

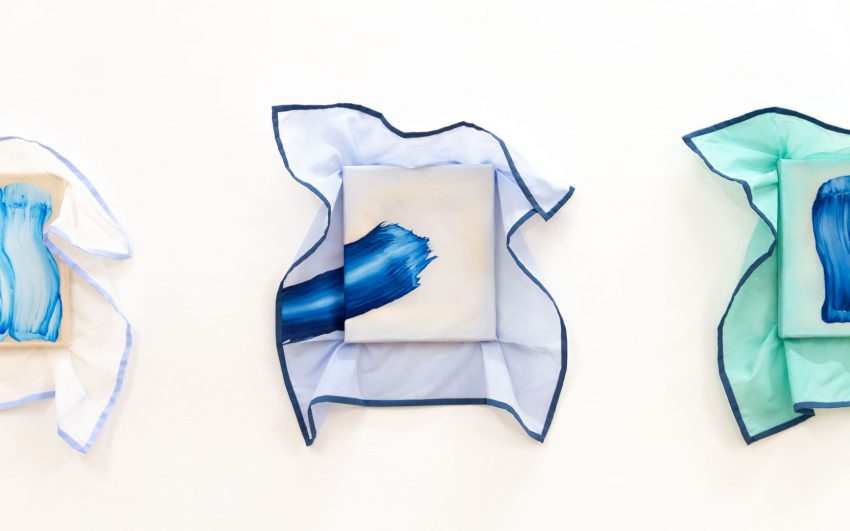

Currently, you have an exhibition entitled “Nichtwissen” [Unknowingness] at Gallery CRONE in Vienna. What is it about?

“Unknowingness” is a phenomenon that is increasingly taking hold of society and politics: the “believe to know,” which tends to overlay actual “knowledge.” Thus, the “Unknown” becomes the categorical imperative and the determining factor of all doing, acting, and omission. In the beginning only a few works were shown in the exhibition room. Throughout the entire duration of the exhibition a display of various media and formats is developing. In this way, the exhibition is completed into an overall work of art, which is the result of constant interaction between the artist and the visitors, respectively the participants of the therapy sessions. Among others two new video works are shown. The current series Sleeping Dogs has been also made a topic. The phrase of the ‘sleeping dogs’, which should ‘not be woken’ is used in many languages – it is reminiscent of the ‘Pandora’s box’ which one is advised not to open. From a political perspective this is currently a very explosive phenomenon. But first and foremost visitors are invited to engage in individual conversation with me.

Interview: Agnes Wartner, Florian Langhammer

Photos: Kristin Loschert