Cyrill Lachauer is a reader of tracks. His works are the result of long travels, which have lead him from the currently much talked about hinterland of the USA back to his own roots in Upper Bavaria and Berlin. In his photographs, films, and texts blank spaces, quotes, and seemingly incidental details become traces of hidden stories that have inscribed themselves into the landscape and characterize them lastingly.

You are a visual artist, who besides photography also makes videos and writes texts. What did you find unsatisfactory about your study time at the Munich Academy for Television and Film (HFF) that prompted you to leave in order to follow your own artistic pursuit?

At the time – I had just finished my civil service and my first extended road trip to California was behind me – I experienced the Film Academy as very confining. In my view, there was a pronounced emphasis on producing that was introduced to early. I wanted to gain more experiences and learn something before expressing myself artistically. Therefore I left the Film Academy and began a study of ethnology. And to be honest: at the time I was panicked by the thought of not having time to spend in the mountains.

In what relationship do your media photography, video, and text stand to each other?

From my perspective, film and text belong on an equal footing with my photographic media. It is exactly the combination of these three media that fascinates me. They result in combinations that I wouldn’t call installations but which function in a threefold form of expression. I consider film and text as presenting the possibility to pose more complex questions. I perceive my approach to photography as more reductive, inasmuch as I use the film camera like a still camera and therefore obtain results in a very similar language to still photography. All three media combine the search for a rhythm, a composition – which remain always fragmentary – and the search for the sound of a certain landscape.

Is it about the moment or the narration in your photographic work?

As in my texts, it is not about narration if you understand it as a classical story containing structural elements. In this sense, I understand my work as non-narrative. However, if narration is understood as something polyphonic, non-concrete, questioning, then my work has narrative aspects for I fall back much more on literary than on art historical references.

Through omissions, blank spaces, and fragments my photography has something narrative, but not from the one whole, from the one story. In relation to my work I reject the term narrative when it is meant to indicate being about something. I don’t tell something about a landscape, a space, a person, and a group. This attitude may appear rather presumptuous in the context in which I move. I try and the emphasis lies on the questioning and doubting search with the landscape, beside her – not somewhere above her.

Extensive traveling is part of your work. Do you travel as a tourist or in the academic capacity of an ethnologist?

Neither! Not as an ethnologist, because I have turned away from science in order to be able to work in a radically subjective manner, I am not a scientist. I travel as a traveler. A traveler is in my opinion, one who primarily has a preference for the nomadic life over the sedentary, who is constitutionally characterized by a restlessness, by unrest, longing, and by wanderlust. Even when he is not traveling, the traveler constantly travels in his thoughts, his dreams; he is both free and accursed. The idea of an escapee never arriving at a safe destination cannot be disregarded. It is a constantly feverish effort, both inside and out. On the other hand, I don’t take the stance of distancing myself from the tourist. This is the attitude of backpackers who think to elevate themselves by differentiating themselves from mere ‘tourists’! To them the Germans on the Ballermann, the Russians on Saint Mark’s Square, the Chinese in Yosemite National Park, and the Japanese at the Oktoberfest represent the ‘tourist’. But this is certainly complete nonsense, for the backpacker is as much a part of mass tourism, a contributor to change and displacement as much as the artist is part of urban gentrification - whether they like it or not.

What fascinates you about the stranger?

It is not about the strange in the sense of the exotic. In order to be able to be contacted, the strange cannot be too foreign.

Just recently you opened a solo exhibition at Berlinische Galerie. The show is entitled “What do you want here.” When was the last time you asked yourself the question: What do you want here?

I ask myself this very often; in view of recent technological and ecological developments this question is essential. What we understand today as being human will change fundamentally in coming years. How will my children live and be able to survive? I believe that the capitalist order of society has no future. Either we destroy ourselves or we rethink. I can’t imagine a life in which my bio-functions are operated by a chip, in which fetuses develop in artificial wombs, in which an implanted cortex will revolutionize our thinking. In Germany we tend to behave as if everything can continue to go on as it is, but this won’t be the case. For me it sometimes feels as Pasolini once formulated beautifully: “And I, a fetus now grown, roam about more modern than any modern man, in search of brothers no longer alive”.

The famous photographer Robert Capa once said: “If your picture is not good enough you were not close enough”. How close you think one can go?

One can go as close as the counterpart, regardless of whether it is in motion or stationary, allows you. For me the question is rather: do I really release the shutter when I am very close?

From 2001 to 2006 you studied ethnology at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich. Even if you are, as you’ve said, not traveling as an ethnologist, nevertheless complex ethnological questions permeate your work like a red thread.

These complex questions are mostly important during the preparation and research phase. As soon as I begin the work, they play only a subordinate role or they take a backseat. Often they are disproved by the realities on location, exposed as inaccurate, overturned, or they suddenly no longer find any power of conviction within me.

From 2012 to 2014 you undertook an extended journey through the American west, from which the multi-media project Full Service evolved. What were you looking for?

Seen in retrospective, my work procedure! That, however, wasn’t clear to me then, but in hindsight that’s what it was! There I developed my vocabulary and liberated myself from wrong ideas which had developed in me during my art studies. Ideas about art that I can’t meet and don’t want to meet.

Why this search for tracks?

Perhaps it has to do with shyness.

What do your landscapes tell us?

I would like to leave it to the viewer to answer this question.

Where does America stand today?

I love America. It is a sick country, but the Western world is sick, including Europe. America challenges me and gives me strength. I experience Germany as ponderous. Since I am a rather melancholic person myself I find that the American tendency toward optimism is good for me.

Trump is doing a lot of damage to the country at the moment, which is being overshadowed by his big talk about the building of the wall and that concerning North Korea. I believe he is doing great damage to the country.

Cyrill Lachauer, The Adventures of a White Middle Class Man

(From Black Hawk to Mother Leafy Anderson), No. E1, 2016/2017, (c) Cyrill Lachauer

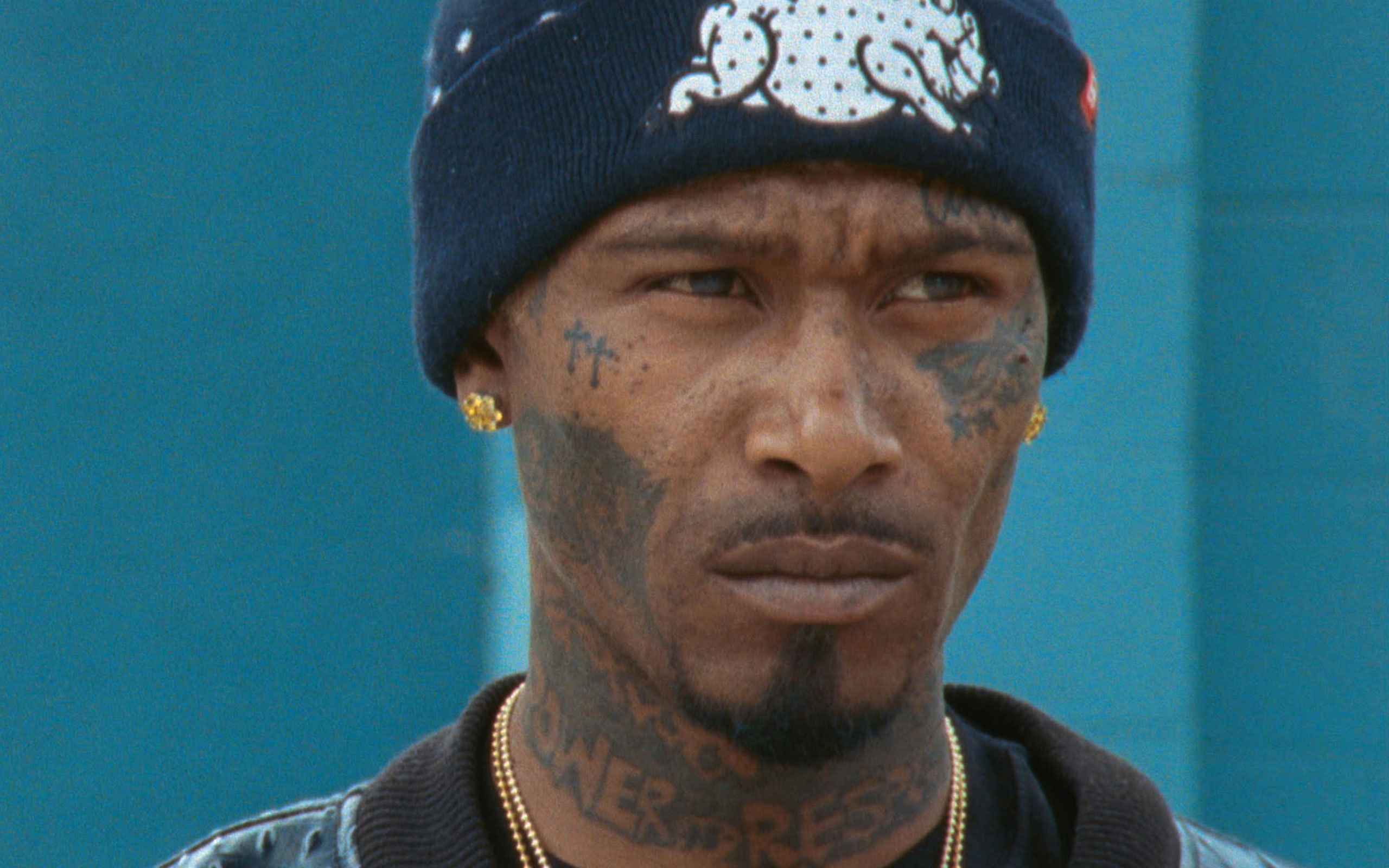

Cyrill Lachauer, The Adventures of a White Middle Class Man

(From Black Hawk to Mother Leafy Anderson), No. I2, 2016/2017, (c) Cyrill Lachauer

One often says: “Home is where the heart is”. Many artists however say: “Home is where my studio is”. Where is home for you?

For many, many years the places of my childhood and youth were my “home” – the valley of the river Inn and the Chiemgau in Upper Bavaria. I still love the view from the lower, hilly landscape of the prealps. But perhaps I can’t go back there. This “home” is now perhaps more a memory of the soul than a real “home”. In past years there existed three homes for me: my family, being on the road, and Los Angeles. In no place do I feel more physically comfortable than in Los Angeles. In Berlin, I’m still a newcomer! And the studio fits basically in two peli-cases: Analog medium format camera and a smaller still camera, a cine-camera, notebooks, laptop, smart phone, and a few books. I dream of building my own “home” one day – a space that simply exists and to which I can return time and again. At the moment, I wouldn’t know where that would be.

Well-known solo and group exhibitions, scholarships as from Villa Aurora, sales: What kind of acknowledgement makes you happy?

Often, especially when my concern is with supporting my family, my moods depend on all of these examples of recognition or of non-recognition, these appraisals and evaluations. That in these moments my happiness depends on them doesn’t leave a good aftertaste. I very much hope that over the years I will discover more and more, something in myself that isn’t so dependent on these external things – especially since in my daily life I prefer to live a withdrawn life rather than one of constant social exposure. It certainly makes me happier when I am able to support my family with my work.

What projects and/or travel have you planned after the solo exhibition at Berlinische Galerie?

It has to become more apocalyptic.

Exhibition view of Cyrill Lachauer What do you want here at Berlinische Galerie; (c) Benjamin Pritzkuleit

Cyrill Lachauer, Dodging Raindrops – A Separate Reality, 2016/2017, Film Still, (c) Cyrill Lachauer

Cyrill Lachauer, The Adventures of a White Middle Class Man

(From Black Hawk to Mother Leafy Anderson), No. M1, 2016/2017, (c) Cyrill Lachauer

Cyrill Lachauer, The Adventures of a White Middle Class Man

(From Black Hawk to Mother Leafy Anderson), No. M3, 2016/2017, (c) Cyrill Lachauer

Interview: Julia Rosenbaum

Photos: Michael Danner

Links:

Cyrill Lachauer's website

Galerie Thomas Fischer, Berlin