Damir Očko has been called one of the most prominent Croatian artists of his generation. His video art, collages and sound installations have been exhibited in major venues including Palais de Tokyo in Paris, and have represented Croatia at the Venice Biennale. But Očko has never lost touch with his roots in Zagreb, where its queer community inspires his art. His new art cocktails are filled with drag legacy.

Damir, do you remember the moment when you decided that you were going to be an artist?

I grew up in a working-class family, life was a struggle and art wasn’t a part of our daily life. So as a child, I never imagined having a career in art. But I remember when I was a kid, I shared a room with my younger brother and every evening we would tell each other a story. It was one long story and every evening, one would continue where the other had left off the previous evening, and I remember how I was taking things very far with my imagination and my brother who was keeping it very basic had to deal with my crazy storytelling. I was also writing poetry and making drawings. So, expressing myself has always been in my life, but I never in a million years imagined a career coming of it. I was also growing up in the 1990s, during the Croatian War of Independence, coming of age as a gay teenager in Eastern Europe, in wartime, you know, everything was really complicated.

And you have been doing art for almost 20 years.

It’s been 20 years since my first solo show in Zagreb. When I was becoming an artist, it was a rebellion because it was totally against the norms with which I was surrounded. I feel like I moved through a lot of spaces and different projects, my language adapted depending on what film I was working on. I like looking back now because it is all so different.

I’ve noticed that your early art was somehow darker. Now your work is more colourful. What caused this transformation?

I wouldn’t say it was dark, but it was a different kind of poetry. I feel what I do now has evolved to seem less serious on the outside, but it is still visceral. This is very important for me, to have a strong gut feeling of what I’m doing. At some point I was saturated with what institutions and galleries expected from me and to some extent too, with what I expected from myself. Sometimes we as artists fall into the trap of becoming a template. There were times I felt really frustrated with these frameworks within which one finds oneself. I guess I was amid a crisis and at the same time I felt there were parts of my life disconnected from my art, such as the fact I was also a drag queen, which at times I enjoyed immensely more than making an exhibition. It was a complicated period. It took a lot of effort to make it make sense to everybody around me in the most unobtrusive way possible. But great things often come as a result of crises. Now it’s balanced.

The name of this drag queen is Aborša Povratilova and she runs her own Instagram page under the slogan “Studio practice gone wrong”. Is she part of your artistic practice?

She has a few names. Aborša but also Miss Dick Maroo, depending on who’s asking. It started as a silly joke with friends. She was not a project and back then I didn’t realize that she was going to take up a great chunk of my life. At some point, I didn’t want her to take any part in my art, because she was sort of a safe space, and I already felt this crisis coming to full bloom. But eventually, her coming out was inevitable because she wasn’t really a joke to me. Through her I asked myself many questions, about my identity, my queerness, about who has the power and the control, and so on. So, yes, she is part of my studio practice, beautifully gone wrong.

Aborša looks fierce. What message does she have for the audience?

If you ask her, she might just say there is no message, because not everything you do has to be loaded with meaning. But I’d say she makes me approach art with more joy and playfulness, and not everything is a matter of life and death, which in art we often forget. I enjoy reading about birds and watching funny cat videos, and sometimes this is enough. I learned that from her.

Do you remember what it was like to take your first steps as Aborša?

My first steps, I’d describe as a real struggle. It took me about a year of practice to understand makeup, body transformation, wigs. There is a learning curve, but I enjoyed it, it was like learning how to draw, but with makeup. How to sculpt wigs and improvise costumes. There is a materiality in drag I love immensely; much of my work is now informed by it. Coming out as a drag queen to my art tribe was a bit of a struggle, too. I was doing drag with my friends in the studio, just having fun as Aborša. At the same time, I was engaging with the art world as Damir. For many people, these two were not seen as coexistent. I was very shy at the beginning in introducing myself as a drag queen. But even if there were some strange reactions, people generally loved and understood it. She was something child-like and fresh, easy to connect with.

Your practice is quite extensive: it includes films, objects, installations, poetry and works on paper such as photo collages and graphic musical scores. What genre comes most naturally for you now?

In the center there is always a film. This is how I think, in layers and timelines and with its complicated moving space, for me, film provides many entry points for all sorts of other media. Collage has always been a very important part of my practice too. It is the media best suited for the mindset of a filmmaker. I always imagine things in layers.

Your recent work consists of quite a range of extravagant cocktails. What is the idea behind them?

I thought of an object that could fit in one’s hand and be a collection of some precious and intimate materials, without having the label of sculpture. After years of doing drag, I had all this residue of leftover materials, like old used lashes, nails, expired makeup, old jewelry, and costumes. Glitter and dirt from precious moments I’ve spent with friends. Something I missed a lot during the pandemic were parties that I used to hold in my studio. So, I started to make these cocktail-like objects by putting different ingredients together in one glass. I list those ingredients as a poem, so the object is at the same time a cocktail and a poem, a physical manifestation of precious time one spends with others.

Some of the cocktails created during the pandemic are exhibited in a new solo show in Kunsthalle Krems called Bird’s milk and other spirits in the summer of 2023. What more is on the menu?

After the pandemic, this is my first big institutional show, which also includes a new film called The Dawn Chorus. It follows the local queer community in Zagreb in the ballroom-like gathering inspired by birds. There are a lot of other works, which derive from the film, including a new group of cocktails and some new surprises. It’s a homage to the Zagreb queer community. For a queer person like myself, as I grow older, I feel that the community around you is what keeps you going.

Where did the name Birds’ Milk come from? I know there is such a dessert in parts of Europe.

Yes, as a dessert it’s popular in East European countries, but in my exhibition, I am referring to a phrase that comes from the comedy The Birds by the ancient Greek playwright Aristophanes. It’s a comedy in which a group of birds tries to trick humans to worship them as the original gods, by giving the deceptive promise that should they agree to worship the birds as gods, humans would receive “the milk of the birds”, a gift of exceptional rarity and otherwise unattainability and which offers eternal wisdom and happiness. So, in line of thinking about what is so special about the community with which I am working in my film, is the idea of it being so precious, especially for someone who came of age in Croatia in the 1990s.

What have you learned about art you do and about yourself during these 20 years?

I learned that change is part of my language. I learned not to take neither myself nor the art world too seriously. I learned that artistic practice is a marathon, not a sprint. You want to have this joy of working, enjoying, and understanding the world for a very long time so it’s good to take things easy and slowly. In Zagreb I can have the slow pace I need.

Damir Ocko, Croatian Pavilion at 54th Venice Biennale, Photo by Aurelian Mole

Aborša Povratilova, Photo by Feđa Hudina

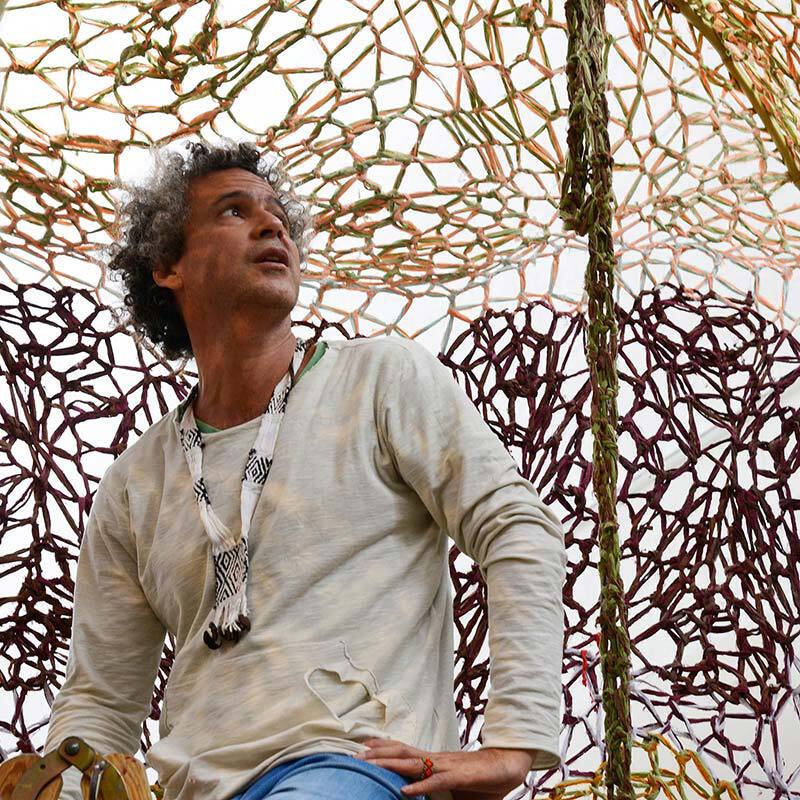

Dragforms, 54th Zagreb Salon, 2022, Photo by Juraj Vuglac

Damir Očko, Studies on Shivering: The Third Degree, Pavilion of Croatia Exhibition view Courtesy of the artist, Photo: Aurélien Mole

Interview: Anton Isiukov

Photos: Damir Žižić