Through a body of personal work inspired by a combination of historical and political events, Danh Vō explores an inheritance of cultural conflict, trauma, and values. When Vo was a child, his family fled Vietnam and settled in Denmark: their assimilation into European culture and the political events that prompted their flight are intrinsic to his artistic investigations. His work sheds light on the relation between the inseparable elements that shape our sense of self, both through collective history and private experience. Exhibiting objects based on the idea of the readymade is a characteristic strategy of Danh Vō; by means of objects charged with symbolism that retain the sublimated desire and sorrow of both individuals and entire cultures, he examines how meaning changes context.

Danh, what was your pathway to becoming an artist?

Some teachers told me that I had a good sense of color and form, so I applied to art school in Copenhagen and finally, after four attempts, I was accepted. After having been accepted, I realized that I was not an especially good painter and that a lot of people were much better than I was. I thought about giving up but in Denmark to receive financial support to study is such a privilege, and since I didn’t know what else I should do, I decided to stay in school and to enjoy it. Rather than worrying about form, color and the other problematic aspects of painting, I decided to not paint,yet make the best of the situation. Unconsciously, I think that at the time that was the best decision I could have made, because in doing so I erased all of the illusions I held of what it meant to be an artist.

It’s interesting that your career began with the destruction of the illusions about becoming an artist while at the same time, art history comes up a lot in your work; has that always been an interest of yours?

Yes, but I don’t think that’s my best quality. I think my best quality is that I have never been very concerned about these categories. I’m much more practical than I am creative, it’s just about doing things and who cares if it’s art or not? I’m just working professionally within the arts, but I think I could have easily worked in many other fields too.

Your work often refers to your own biography and one of the things that is often mentioned in relation to your exhibitions is the fact that you regard love affairs, popular culture, and geopolitical circumstances as of equal importance when it comes to the formation of a person’s identity. In your show at the Guggenheim, for instance, works about the Vietnam war, from which your family fled, were positioned alongside works that referenced failed romantic relationships…

I never saw the differences between those things. Somebody else has set up those terminologies. I mean, first of all, I’m not even a first-hand witness of the Vietnam War, but if I’m dealing with that, if I look into my father, if I look into that war, what I still don’t understand today is that people talk about it as a personal issue. It was one of the most significant global geopolitical events during the last sixty plus years, you know. And then people say, “Oh that is personal,” which doesn’t make any sense.

In your recent exhibition at South London Gallery you included paintings by your old professor, Peter Bonde, as well as curating an exhibition within an exhibition dedicated to the work of artist and curator Julie Ault. Is that the first time you’ve tried your hand at curating?

No, I actually curated the exhibition Tell it to my heart: Collected by Julie Ault at the Museum für Gegenwartskunst Basel in 2013 and, before that, I curated a show on Felix Gonzalez Torres at Wiels in Brussels in 2010. I think it all comes from my mentor, my friend, my everything, Julie Ault and her brain. I think all these things come from her.

Another artist you’ve frequently come back to is Isamu Noguchi. At the South London Gallery, you installed one of his sculptures at a nearby housing estate and I noticed you also have one in the grounds connected to your studio. What influence has his practice had on you?

I discovered Noguchi about five years ago and he’s been a really good anchor point for me. What I learned from him is that in art you have this beautiful thing where you can formulate a certain way of thinking and with that thinking, you can apply it to whatever you want because who cares if it’s art or not art? That’s what Noguchi did. If he made lamps, then he considered them sculptures.

Where does your collaborative approach to making art and exhibition making come from?

I always say that there are very few geniuses in the world and if you’re not one then you had just better gather the best people around you.

When it comes to being inspired by other artists what attributes or qualities are you looking for?

That they work to the limit of what they can do. That’s what attracts me to another artist’s work.

You’ve also done some teaching in the past. What advice did you try to impart to your students?

One strategy I always follow when I teach is to never make studio visits. Art students are so conditioned to argue for their own work and it’s something I just don’t want to listen to. I tell them, “Tell me anything. Tell me what you’re interested in — what book, what film, what building, whatever, I don’t care — and tell me why you like these things.” And then I will talk with them about those things, but I never do studio visits. Not everyone likes that method. I didn’t teach for a while because I was kind of traumatized when I was in San Francisco and one student wanted his money back!

Looking around the grounds of your studio, which has two workshops, an entire barn for storage, and a series of vegetable and flower gardens, it’s easy to see why you might want to live here. But I’m interested in what made you decide to make the move from Berlin to Brandenburg at the height of your career.

Well when I found this piece of land, I was originally looking for a storage place. If you’d have asked me three years ago… I was afraid of rainworms! (Laughs.) I would never have guessed that I would end up moving here. But then I had some land, so I thought, okay I’m going to get a little bit into planting and then suddenly it just took over. This place this really changed my life because I meet all these young people who are very concerned about food production and how to grow things in a better way. So, I got totally involved in those questions and I’m trying to see if I can somehow participate. They’re the ones with the expertise, but I’m a very good organizer. So, I’m trying to see how I can get myself involved and make this work economically. I don’t know where it’s going but I think it’s going to takeme somewhere totally different.

Your studio seems to be full of flowers right now. Are they for an upcoming project?

No. It’s because I am opening a flower shop. It’s going to be a regional shop, selling flowers and produce that is grown here in the studio but also from the friends I mentioned as well as local farmers. It’s going to be run out of my old studio in Berlin, which is this beautiful 19th century former shop.

Living here has obviously affected your life, but how do you see it affecting your practice? I was looking around and I noticed that so many of the religious relics you use in your sculptures are installed in the grounds. Does it change the way you look at these objects to be able to put them outside?

I’m very intuitive when I work and most of it comes from empirical experience. The best decisions are the ones that take you in a different direction than you were expecting. I think that that’s what’s happening right now. It’s exciting. I can feel that I’m changing but I don’t know what the results are going to be.

Has it been like that since you moved here?

No, it’s just been a very slow process. To be very honest with you, I think it was really recently that it [his time in Brandenburg] became more defined. And the only thing I can say is, no more bullshit. That’s the only thing I know that I don’t want any more in my life.

And what is bullshit for you in this context?

Anything that is not necessary.

You’re opening an exhibition at Secession in Vienna in September. What can you tell me about it?

There are lots of practical things to work out at the moment. I’m not doing a catalogue, for instance. I think we’re going to do an edition instead and the money will go towards making a new flowerbed or towards getting bees, which is something we’ve been thinking about at the studio. I think books are fantastic when you have the right idea, but for an institution it often boils down to branding. One of the most beautiful catalogues I did was for my first exhibition at the National Gallery in Denmark. I told them that if they wanted to do something for prestige then we should put all the money for the catalogue into a beautiful invitation card and we made a pop-up birthday cake instead. Sometimes, as Felix Gonzales-Torres once said, you just have to redirect the circus.

Is there anything that you’re working on right now that you’d like to mention?

I’m working on liberating myself. I’m going to make a structure so that I don’t need ever to think about money again, and I think that would liberate so much time for me to think of things that are more relevant. I can’t deny that I did certain shows, even museum shows, in order to get certain things running. But that’s the hamster wheel that we are caught in and I want to get out of it. That’s what I mean when I say cut the bullshit. That’s really what I really want to concentrate on now. I am so privileged that I can do one gallery show and have run all this [his studio] for two years now — but I don’t want even that disturbance. How meaningful would it be if I could have 100% concentration on one thing? Not because I want that, necessarily, but my ambition is to have the freedom to choose.

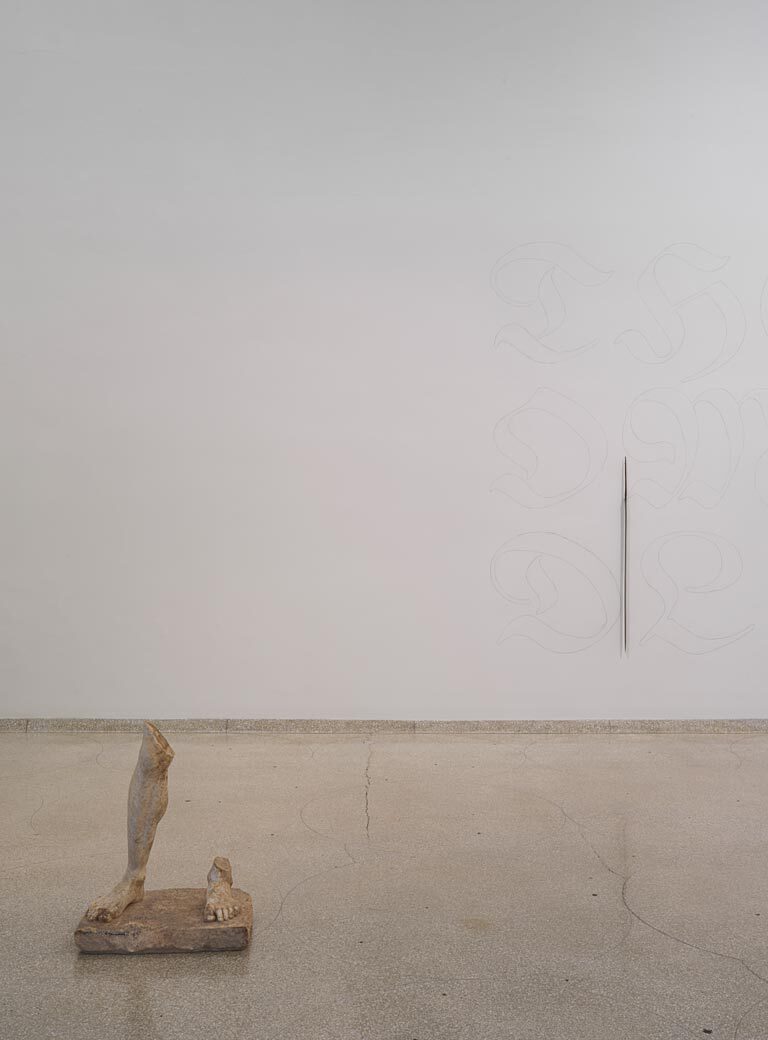

Installation views: 'Take My Breath Away' Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, February 9–May 9, 2018, Photo credit: Nick Ash

Installation views: 'Take My Breath Away' Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, February 9–May 9, 2018, Photo credit: Nick Ash

Installation views: 'Take My Breath Away' Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, February 9–May 9, 2018, Photo credit: Nick Ash

Installation views: 'Take My Breath Away' Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, February 9–May 9, 2018, Photo credit: Nick Ash