Daniel Gustav Cramer is known for his reduced yet complex spacial compositions using various media including film, sculpture, installation and text. His photographs, for example, show quite unremarkable scenes, which are open to interpretation – snapshots of the moment – with minimal action, yet emanating a lyrical narrative force that addresses the imagination and causes the viewer to ponder. Often, the artist is concerned with the human presence and the invisible relationships between man and the environment. One could describe Cramer’s work process as a constantly growing archive containing the reflection of moments and examinations of found objects, which he is always ready to capture.

Daniel, can you describe the essence of your work?

In my mind my work has an alter ego: songwriting. I am very interested in the sculptural qualities of images, sounds and texts, the abstract forms these works evoke. I am looking at the different relationships that we have with nature, with systems that strive to define human affairs and with the things we know exist but can only be sensed. We create a picture of the world, and another one, and many more. And constantly replace older ones. Time and again I return to certain landscapes – to places where the weather can be felt.

How do your works develop? Is there an idea at the outset that you try to realize?

The most important works often happen incidentally. For example in Kumano, a forest area in Japan where I worked on a project, I stood during a brief break in a small harbor and noticed a school of fish near the pier. The water surface reflected the sky and clouds. The presence of the fish below the surface were only revealed by the movement of the waves they caused. I grabbed my camera and filmed the scene. Other works, for example a book that describes all objects orbiting the sun – planets, moons, meteorites or dwarf planets – evolved after months of research.

Scenes like the one you describe in the Japanese harbor appear at first rather banal. Your photographic series Tales is concerned with similar, hardly spectacular scenes. If they were vacation shots one would probably edit them out…

I understand what you refer to when you mention a certain banality in the content of the images. The scenes are rarely spectacular. However, each picture captures something worth seeing, sometimes it is only a minimal gesture. Every photograph I take is taken with the hope that a possible narrative will unfold. Later, in the studio, I can see whether a sequence can actually be found that will yield a small story from the various pictures – or from one individual photograph. It is through repetition of a similar image that these narratives begin to emerge. Often almost invisible changes can generate the most intense moments.

Are you always ready with a finger on the shutter release to capture these situations

In a certain way yes. As a child, I used to climb with a friend up the drainpipe to the flat roof of our house. Lying on the roof we looked into the adjacent gardens watching the neighbours mowing the lawn, reading their newspapers, we observed them through the windows inside their houses, cooking and tidying up. From up there the gardens appeared like stages of a theatre – the neighbours were our silent protagonists. At that time, I developed an eye for a kind of miniature drama from specific perspectives. When I am traveling today, I always carry the camera with me. When I drive my car the camera lies in my lap, when I’m eating it is beside my plate. I check the light meter often, without taking a photograph, so that I can react immediately in case I notice a scene in front of my eyes.

You photograph only using analogue, one senses that…

Yes, I like the directness of analogue photography – it is what it is. Light passes through the lens, the film is exposed and once the negative is developed in the darkroom, light travels through the negative and creates the photographic print. There are no pixels involved and unlike digital photography there is only a minimal range of possibilities by which to modify the outcome. Digital photography gets better and better. In opposition, analogue photography is already perfect and has been from the beginning, because the image becomes visible by a combined chemical and technical process enabling it to achieve a certain character of a document. Today, in relation to digital, analogue appears almost physical.

What kind of cameras do you use?

For the Tales series I use a 35 mm Leica camera. I also work with a large-format camera, and a classic Hasselblad 500MC I inherited from my grandparents.

Some of the Tales are arranged as groups of individually framed photographs that except for minimal changes of the picture section or a detail in the image are hardly distinguishable from each other, why?

They are nevertheless different moments, even if nothing apparently seems changed from one to the other, they are the result of different exposures. In some images just the position of a bird in the background for example is an indicator of this. In any case a fragment of time has passed between one image and the next. The gaps framed by two photographs of a Tales series are the area where the mood and story is made.

How do you choose the individual images that will make the final work?

I am looking for abstract shapes that are formed in the sequence of the individual images, there are movements and tensions unfolding. In the case of the boat on Lago d’Iseo I follow the line that the boat draws in the water from the first to the last image. It reminds me of Richard Long’s A Line Made by Walking, in which he repeatedly walked up and down on a certain piece of meadow until a temporary trace became visible in the grass. The boat draws a straight line. I chose six photographs to build up this spatial event, selected from perhaps twenty negatives. However, basically I try to capture a moment that stands within a larger context using as little photographs as possible. For example, I photographed a man snorkeling off the coast of Cyprus. The first image shows him swimming to the left, on the second he swims upwards, on the third to the right, then in the final shot he dives into the depths of the sea. His movements correspond to the positions on a clock face; 9 o’clock, 12 o’clock, 3 o’clock - in the last photograph he leaves the two dimensions of the circular shape.

In this case does the identity of the protagonists play a role?

No. On the contrary, it is very important to me not to reveal the photographed person’s identity. These photographs emerged simply from my observation and the protagonists were oblivious to my presence. The intimate sizes of the photographs makes it impossible to see facial features, since the figures are documented from a distance.

Regarding observation, since drones are now readily obtainable, one no longer needs to ascend to the roof to look into a neighbour’s garden as you did as a child. Would you consider the use of a drone as a work tool?

I do use a drone occasionally, I recently completed my first film, Aphrodite, which is comprised exclusively of drone shots. It features two rocks in the Mediterranean Sea, one off the coast of Cyprus, and the other off the island of Mallorca. Currently, I am working on a film in Romania, using aerial photography, a kind of vampire film.

How could one imagine a vampire film filmed by drones?

I was planning to produce the film years ago, with Phillip, a school friend. It seems that the film will end up to be a lot more about our friendship. The setting frames the mood: Transylvania, clouds that hang over the forests and glide across the mountain ridges. Bram Stoker’s and F.W. Murnau’s imagination concerning the blood craving specter who sleeps during daylight hours in a coffin; and our journey itself. The nights, the conversations. I don’t want to give away too much.

In general, your art always seems to leave the viewer in a state of uncertainty. It doesn’t reveal much…

Yes, that’s true. It addresses the imagination and leaves room for one’s own interpretation. Last year I had a solo exhibition with Vera Cortes Gallery in Lisbon. One work in the exhibition was titled Empty Room. I travelled with Vera to a pear farm, about an hour north of Lisbon. We emptied one room in the main part of the farm and closed its windows and doors. The work was the content, the volume of the room. Once a window or door was opened, the work would no longer exist. In the exhibition space in Lisbon there were two references to this external work: a small publication comprised of a conversation between Lukas Tőpfer, a Berlin-based writer and curator and myself discussing the parameters of this installation and its influence on the Lisbon exhibition. The second reference was the invitation card. It depicted a sandy path lined by trees, the road to the farm. It was impossible to experience this work physically, yet it had a presence in the exhibition.

Do you use the German term “Poesie” in connection with your work?

I feel uneasy about the term “Poesie”. Today it rather applies to poetry collections or sentimental emotions. I prefer the English, similar sounding term “poetry”. I try to capture a mood, a moment that turns into something sculptural in the work. In my works a seeming silence and restraint appears on the surface. As soon as one breaks through this layer, an intimate dialog opens up between the works in the exhibition and the viewer – one which is perceived different for every visitor and which relates to their personal experiences.

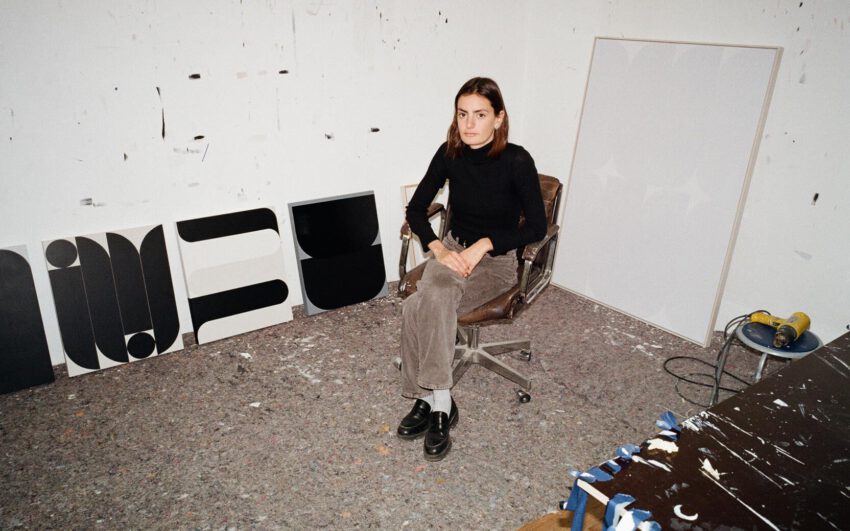

Are all works created in these spaces?

Yes, at least a very substantial part. Here I plan, write, make sketches and decisions. One table I use to edit films, on another I work with my hands, in the small room I mainly write and sketch. In the center is a larger table on which everything lies that is in the process. I develop photographs in a darkroom and test them here in the studio. I prepare most of the sculptures here and collaborate with a handful of producers on their realisation. For my books I work closely with a Berlin-based bookbinder.

We just discussed how your art involves not only photography and film, but also text, drawing, sculpture, and installations. In 2017 for example, you had a comprehensive art project in Iceland which incorporated text and in which you also examined the island’s geography. Can you tell us something about that?

The exhibition space Hjalteyri – a former fish factory –is located at Eyjafjöður, a fjord in the north of Iceland. I showed five works: one consisting of 100 metal rods that were positioned within a radius of perhaps 30 square kilometres on both sides of the fjord. The rods had the height of an average Icelander: 175 cm. These objects stood in private homes, public buildings and in the open landscape. One could find them at the bakery, in the town hall, at the airport, at the water’s edge, underneath bridges, in bedrooms and so on. Not a single rod was visible in the exhibition space, only a list of their positions. Two things were important to me: on the one hand this work was an abstract portrait of the entire region, of the fjord, the people, immersed in the landscape. On the other hand it was also a kind of sculptural drawing. I always imagine, how the rods would look seen from high up, with an x-ray machine so-to-speak – rhythmic lines that exist temporarily in the private sphere as well as the surrounding landscape.

You studied at the Royal College of Art in London. How did it come about that you decided on a career as an artist? With your visual acumen and eye for specific situations, you might have become for example a reporter or travel photographer.

I started drawing early, at the age of six I drew almost every day. Looking back, I always had the wish to give form to what I experience and to what I happens around me. For many years I kept diaries – the final thesis of my first study was a diary as well with a group of abstract photographs. During my school years I played passionately in a band, I spent plenty of nights as a DJ. Reportage photography never interested me. It was always very important to me that the core of what I do is not determined from the outside but rather arises from somewhere else. In the Tales series, for example, an essential part is the journey itself. Yet its not the place but something that happens there, however insignificant, in one instance - and then its gone. Tales (Akropolis) shows two visitors in Athens, who lean forward to look at a detail of a ruin. The viewer of this scene, the camera, doesn’t see what the two are looking at. There is a focus on looking itself – our glance is passed on through the viewers’ eyes. On the other hand it concerns things past: we don’t know what the two men are confronted with – and perhaps even they don’t know it exactly. Past things, here and yet inaccessible.

Do you have a central artistic concern or something on which you work that pervades your work independent of the medium?

I am always concerned with relationships: Between two people, between man and nature, the past and the now, and perception – there are numerous theories of what it is, the world, time – from the flat Earth theory to Hawking’s curved or warped time concept. We know for sure that the open questions are still more numerous than the answers that we have found. Therefore literature is so important to me. There in particular the approaches to these questions are precise and life-related. I return to Proust’s reflections on memory or Kawabata’s descriptions of what remains unsaid.

Do you know in which direction you want to develop your art, for example to continue to pursue a specific medium or a specific topic?

I see my works as fragments of an archive that is growing over the years. This archive ranges from photographs of moments to examinations of collections, for example sightings of the Loch Ness monster, UFOs, or a research on numbers. It ranges from visual or object-like commentaries regarding time and the perception of it to images of friendship, memory and love. There are still many topics that I want to work with. The archive and its elements will transform with the years.

What are you presently working on?

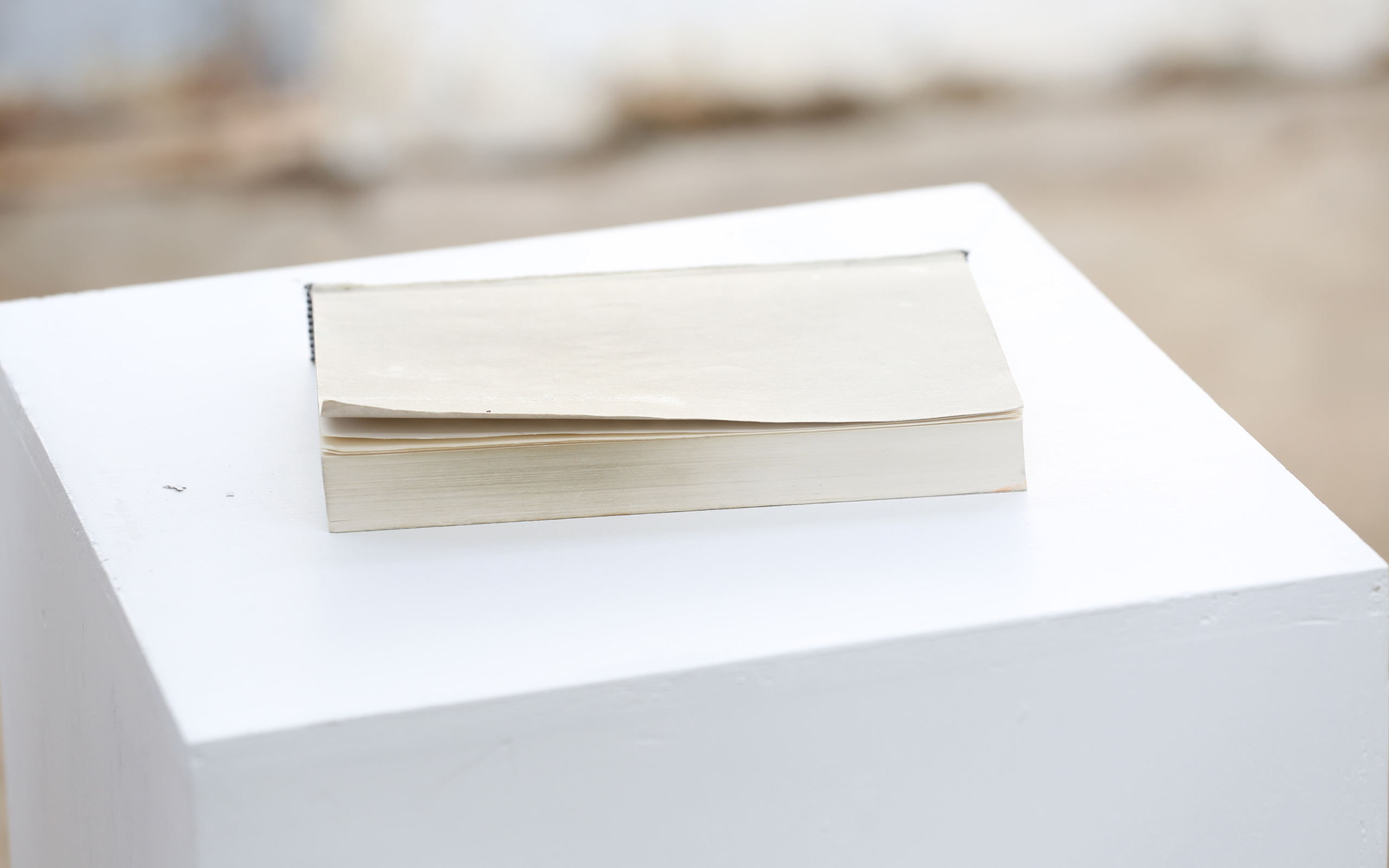

At the moment I am working on a short film about the wind, a show at the Centre Pasquart in Biel and a project in Paris with two wonderful collectors, Piergiorgio and Iordanis. I have been invited by the Société Suisse de Gravure to design a book edition for their centennial anniversary. After one year of preparation I have just completed this project. I have produced 125 books – each one a unique item.

Daniel Gustav Cramer, Tales (Athens, Greece, October 2010), 2015, C-print, 25,5 x 20,5 cm, framed

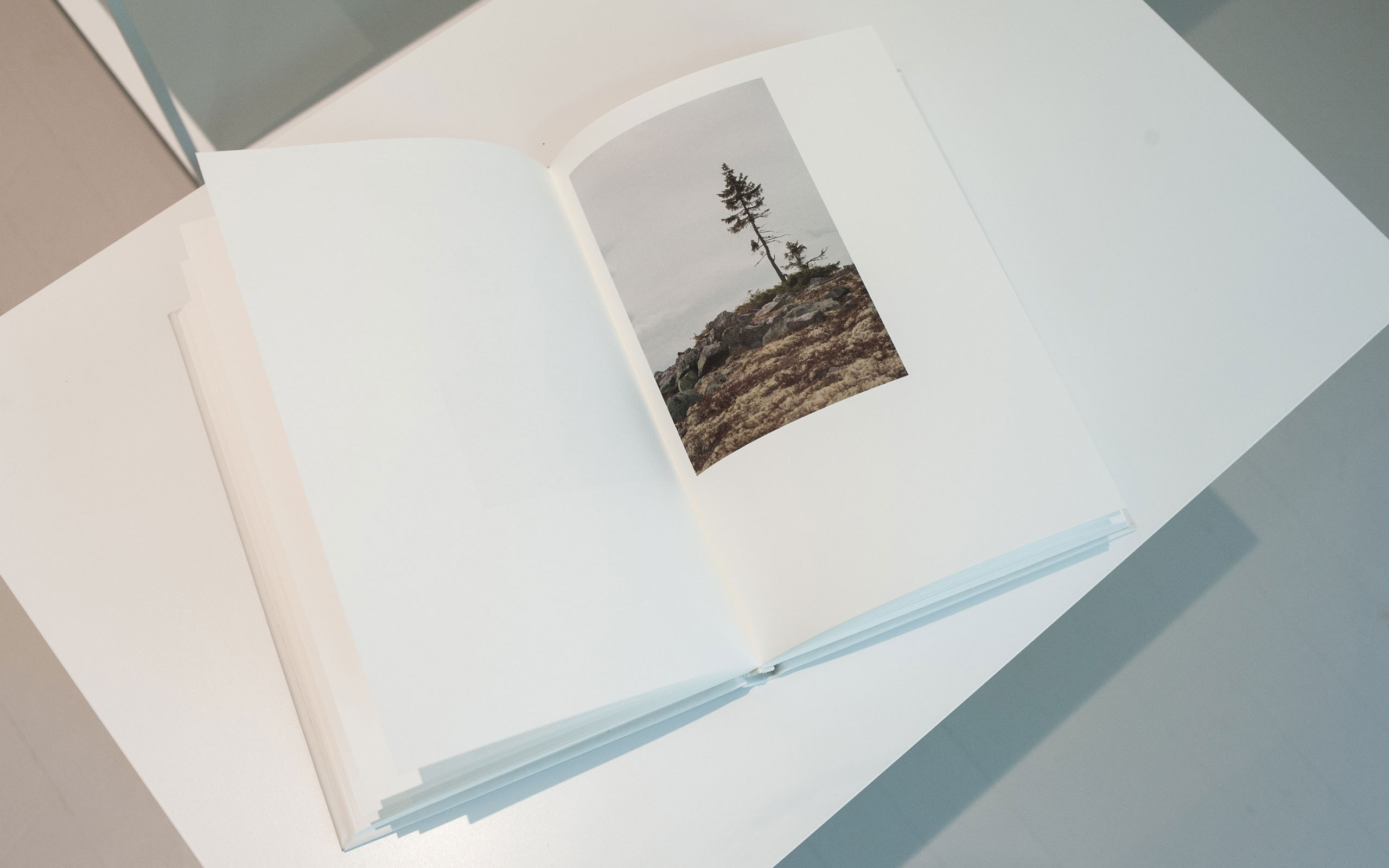

Daniel Gustav Cramer, Untitled I, 2013, C-print, framed, 143 x 107 cm

Daniel Gustav Cramer, Objects, 2010, Book, 280 pages, 18 x 12 cm

Daniel Gustav Cramer, Katherine, Northern Territory, Australiia, May 2009, 2017, 7 stack of text, each 29,7 x 21 x 4,5 cm

Daniel Gustav Cramer, Coasts, Basel, ArtBasel Parcours, 2016

Interview: Florian Langhammer

Photos: Kristin Loschert

Links:

Daniel Gustav Cramer's websiteBolteLang Galerie, ZurichGalerie Vera Cortês, LisbonSies + Höke Galerie, Düsseldorf