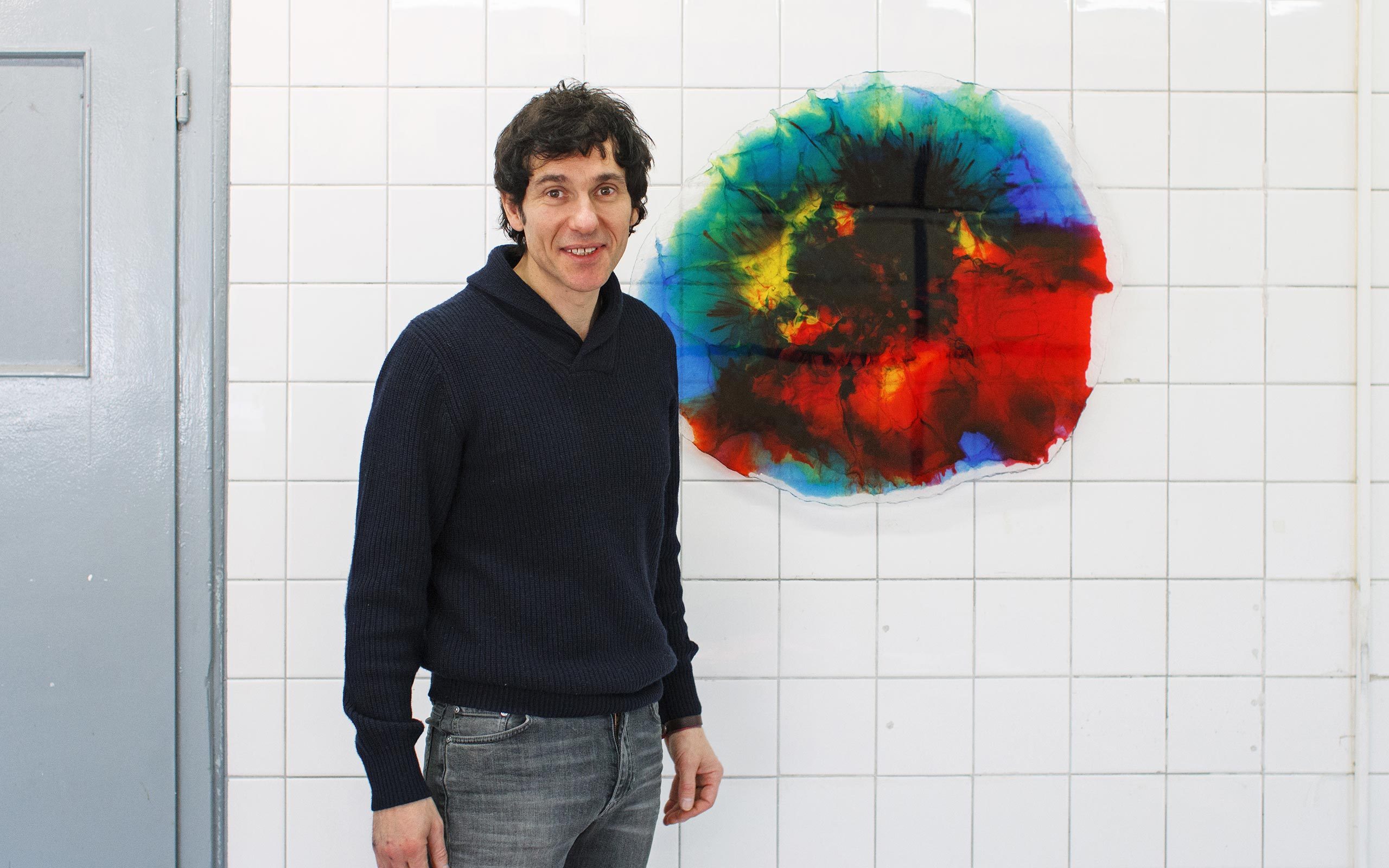

Daniel Knorr’s work could be described as sculptural in the broader sense and characterized by its complexity of content. His "materializations", as he calls them himself, are observations and, quite often political, conceptual thoughts, which seek ingenious forms of expression in enclosed or public spaces, that are not restricted to particular media. In 2005, Daniel Knorr represented his home country Romania at the Venice Biennale, where he triggered a polarizing debate about his "anti-concept" of an empty pavilion. We met Daniel in his studio in Berlin-Lichtenberg to talk with him about how he came to be an artist, to talk through the thinking behind some of his most prominent pieces, and how Romania’s prime minister had to apologize on his behalf.

Daniel, you’ve been well established in the international art market for many years. When and how did this interest in art actually begin for you?

It began when I was sixteen. At age fifteen, I arrived in Weiden, Oberpfalz in Germany where my father had found work, this being the reason why we moved there. At age thirteen, I read Inferno and Ecstasy by Irving Stone – a biographical novel about Michelangelo. On reading that, I thought that Michelangelo was extremely cool, but at that time, I didn’t anticipate that making art would be in my future. In school I took an honor course in art and recall that I did a large painting showing a worker making a sandwich in from of a huge machine. The painting was subsequently chosen to be hung in the school.

Art seems to have interested you from an early age, did your parents support your interest?

My father suggested to me to simply avoid work and sleep (laughs).

But you decided to become an artist.

Yes, I really wanted to make art. I think it was a kind of liberation, I had the urge to be free, to actually escape from everything. At first I tried the art academy Nuremberg and showed my portfolio. They said, "Forget it!" I had in fact produced a big show that might have been too eccentric for the professors. I told them all about it, and then jumped on the table. They weren’t prepared for that (laughs). With Daniel Spoerri at the Academy of Fine Arts, Munich it was different. He was interested in my work, but his professorship ended that same year which threw me back.

Eventually, I ended up with [Martin] Zacharias at the Academy of Fine Arts, Munich. It turned out to be rather more concerned with art education; therefore I had to get out after two years and find a free class. Some of my co-students at the time didn’t understand my spatial experiments, they went to the professor and complained that I was crazy. I realized that I didn’t really fit into the group and left. For quite some time I worked outside the academy, making works for the public space.

What happened after your studies in Munich?

After five years of study I stayed one more year in Munich. Then I left for the United States and registered at the University of Vermont. It was a tremendous change. I had really begun to feel at home in Munich. I knew the city quite well and people knew me, I felt somehow that I belonged. In America nobody understood what I was doing.

I can imagine that, because many of your works are quite polarizing. I’m just thinking of the children’s drawings with cocaine.

I couldn’t get anywhere at all with such works in the US. In Munich, too, the works had polarized. The professors didn’t really know whether or not they should be on my side; but the work was quite successful. Olaf Metzel, with whom I studied at the time, found them okay and supported me all the way. At the time, I borrowed 500 grams of cocaine from the police and informed the police spokesman what I was about to do. He was open and cooperative and I found it actually good that the police were open to publically supporting something like that; he actually came to the academy to view the work. It caused a great deal of public interest, and many asked what it was all about. Ultimately, an enormous amount of public criticism developed, largely because of the police involvement, many people couldn’t understand why the police had provided support to me.

After your sojourn in the US you moved to Berlin. How did you experience the city at the time?

The late1990s in Berlin were mega-cool. In the beginning, I had difficulty in catching up, the art scene was very political, it was a time of change, a new beginning, most galleries were still very new.

That the art scene in Berlin was very political must have suited you because your works are highly political, aren’t they?

My art can be perceived as political; I leave that to the observer. I am interested in the structures and conditions of our society in the present time and this is what I process. To me art has the ability to represent the state of things as they are at a given time. This certainly includes the sciences, sports, and the media however, they all serve one media. This is not the case with art. Art represents, and at the same time one is represented by art. It’s very sensitive terrain and that’s why it can be so heavily criticized.

So you see the role of the artist as a critic of society by confronting society with its own image?

Yes, but I believe that happens anyway, because artists always represent their time. Each artist finds his or her place in art history and of course that applies to contemporary art too, art communicates current events to the people. Some say, "when words no longer function, art sets in". That may sound a little corny, but it contains some truth, because art is truly a separate language; it reveals as it were the location and time in which we exist.

Are you saying that art has a great representational character? Because in that case, I would refer to the Biennale di Venezia, 2005, in which you were chosen to represent your home country of Romania.

That’s true. It was really my first international appearance. European Influenza, the work that I made for the Biennale was strictly speaking the continuation of a work that already existed. It was originally developed for a New York gallery, shortly after September 11, 2001. At the time, I left the entire exhibition space completely empty. The work for the Venice Pavilion was a new materialization. It was a new interpretation of this work, a criticism directed against Europe, against its frantic expansion and the structure of the European Union. The same year, in 2005, Romania signed the contract to enter the EU. As we can see today, not much has changed. Europe continues to be built on the military, economics, and territorial concepts. Many resulting problems have long since arrived in our daily life. I wanted to communicate a new critical view; the free of charge reader edited by Marius Babias and including essays by Boris Buden, Bojana Peji, Piotr Piotrowski, and Dan Perjovschi has in part contributed to it as the work’s first materialization.

As an artist one is always exposed to public criticism when exhibiting one’s works. To be chosen to represent one’s home country at the Biennale di Venezia surely generates another dynamic, especially when the contribution concerns an explosive topic as you’ve chosen.

That’s true. The idea for the concept of the Venice Pavilion had been selected beforehand. It was clear to everyone what I planned. When my project publicized by the media, an avalanche of criticism was triggered, first in the national newspapers, followed by the first questions from the Romanian parliament. Eventually the prime minister had to make a public comment regarding the "shame of Venice". The work also found great international interest. The Guardian described my work as "non-work". The International Herald Tribune on the other hand found that it was one of the best works at the Biennale and deserving of a prize. The work polarized tremendously.

How has the Romanian government dealt with the situation?

I still remember that Horia-Roman Patapievici, the director of the Romanian Cultural Institute – a personality whom I greatly respect and who unfortunately is no longer in office – initially did not really like my work but regarded it as rather comical. The Romanian delegation came to Venice with a rather queasy feeling. They were quite afraid of what would happen, how they would look in front of the public, and the pavilion was empty. When visitors eventually showed up, they were congratulated. Later, during the reception, Romanian refugees were in the street singing. They even came to our table and the cultural minister at the time joined their singing. Unfortunately I have no photographs of that. It was a stirring situation! I have had to explain it often and I’ve said repeatedly, "I don’t fool around. It is not about Romania being spoofed". Years later, I was still addressed by people saying, "Ah, that was you at the pavilion!" I thought it was very interesting that people still remembered.

As an outsider one thinks that an artist who was shown in Venice will automatically rise through the ceiling.

No, that wasn’t really the case. After the Biennale no invitations for shows came in. I had put some money from the Biennale year to one side and was able to make ends meet. After the Biennale, people certainly knew my work and it was still talked about. But I think it takes time. One has also to grow into this role. During the Biennale I met Adam Szymczyk who invited me to participate in the Berlin Biennale in 2008 and in a big show at Kunsthalle Basel in 2009. On the last day of the Basel exhibition, gallery owner Giangi Fonti looked at my work. He invited me to participate in an exhibition in Naples, which became the beginning of a long collaboration.

In 2008 you showed a work consisting of flags on the roof of the National Gallery in Berlin. Can you talk about that?

Yes, I installed the flags of the 58 student accredited associations in Berlin on the roof of the National Gallery, waving as a "frieze of flags". With this project I wanted to question German history and the national concept. This work has been very important for my career as an artist, more important than the work in Venice. Subsequently I received many invitations to exhibitions, and the interest of the press and the public was great. A very beautiful publication accompanied the work. Everything takes its time, sometimes days go by without anything happening.

Let’s return to the "materializations" which you’ve repeatedly mentioned. What exactly do you mean by them?

I understand my works as materializations of concepts. Earlier I used to call them invisible works although they are not really invisible, because they are documented, by the viewers, the press, in fact even this interview "materializes" my artistic practice. The viewer’s discourse with the work reflects exactly what we are and what we represent – therefore materialization. The work Ex Privato for example is a materialization which I have exhibited at the Manifesta 7 in Bozen. The idea resembled that of the Venice Pavilion, at the same time it was different.

I wanted to transform a venue of the Manifesta into a public space that was to be open twenty-four hours a day. In addition to me, other artists were represented and exhibited their works. All participating artists thought the idea was super and changed their contributions accordingly. We removed all of the doors from the building. It was completely open, even overnight. Nobody took advantage of the situation to destroy something deliberately although someone took the opportunity to react to a work that was to represent them; they slit the projection screen in a Fontana-like manner. It was a somewhat political act. After that incident a night watch was organized which had not been my intention, ultimately, perhaps, it was appropriate; this is exactly how public space is experienced today, freedom materialized through security.

A conceptual work is not a picture that can be hung on the wall. How does one actually sell a conceptual work?

Such works are really hard to sell; it is also a question of in which form they continue to exist. In the case of Smoking in the museum I have often spoken with the Kunsthalle Bremen which bought the work, and explained how the work is defined. In Smoking in the museum the intention is mainly to show that smoking historically documents a reflective cultural position and how smoking can take place today. The installation consists of a smoking cabin, of pictograms that point in the direction of the cabin, "Smoking Allowed"-sign on the entrance on which the cigarette is not crossed out and certainly smoking people in a glass room between the pictograms. Everybody connected smoking with the cabin. But I think the idea of Smoking in the museum also functions when someone in the museum lights a cigarette butt directly and smokes without a smoking cabin. It is rather a reflective attitude towards smoking as such and partly a health debate, in which the state tells us what we may do and what not, a kind of deprivation of self-determination. The smoking cabin serves as a description of a relationship between the state and its citizens at a certain moment. At documenta 1 [Konrad] Adenauer didn’t need a smoking cabin when he smoked his cigar. The museum has bought the work, however without the smoking cabin. It was sent back to the company that made it and the work continues to exist merely as a concept. If the museum were to say: "Today we can smoke in the museum without the cabin", the work would be immediately re-materialized. If a private collector had bought the work, he could for example light a cigarette in the company of his artworks at his home; even that would re-materialize the work.

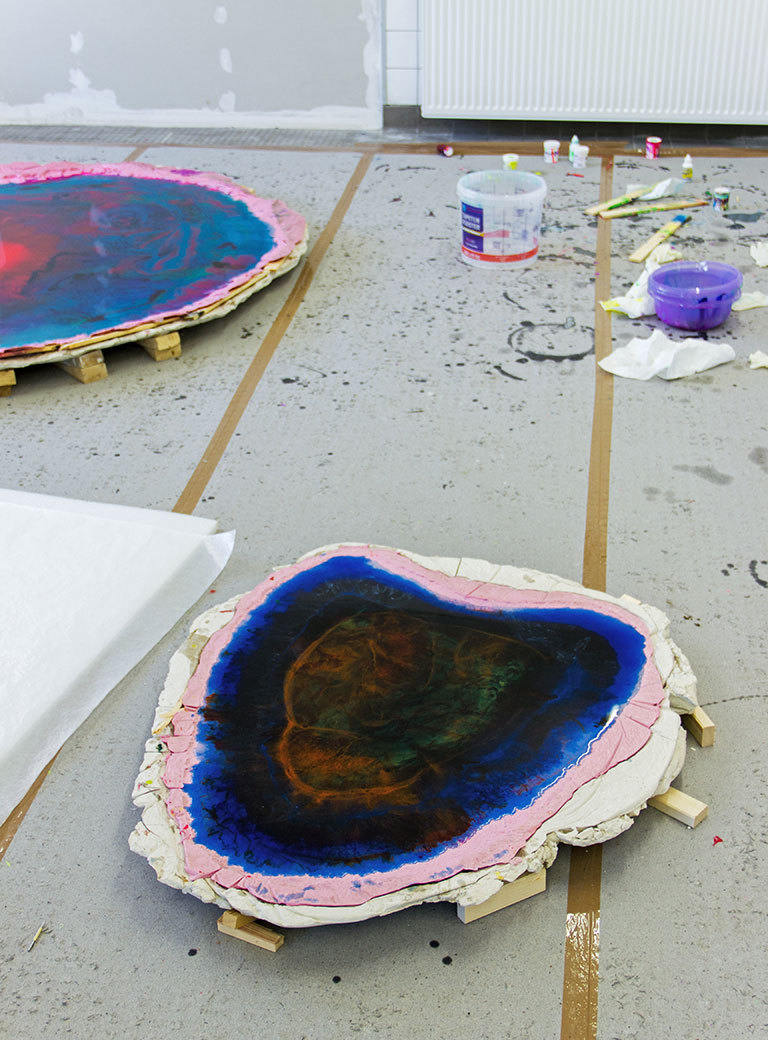

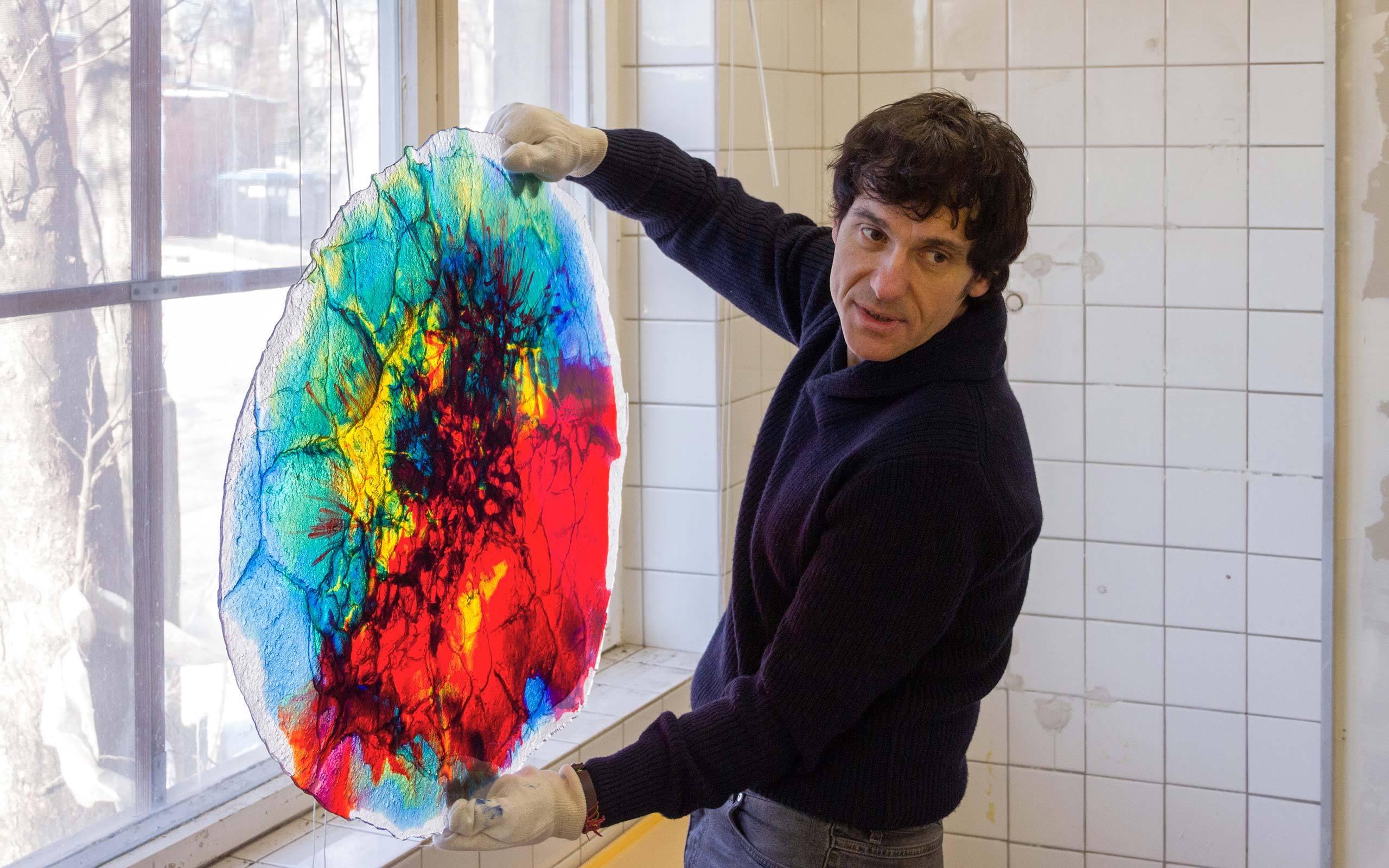

In your studio there are a lot of castings. Are they another form of materialization?

It is resin poured into a form that I have cast from street surfaces and manhole covers near the Pont Neuf in Paris. While the resin is hardening, I add various colors. At first I experimented a lot with red and black. Just now it is becoming a bit more colorful. The castings depict exactly the structures of the surface of the street where I took them, for example this puddle. On a historical level, the castings make a visual link between two bio-political structures, in this case the gallery wall (architecture) and the street. The architecture itself can be seen as a measure to structure society and to design it ergonomically. Street construction itself is designed to increase productivity and efficiency, to get faster from A to B. What becomes visible here, materializes if you will, is our existence, the traces we leave behind in the anonymity of the flat street level. When the work hangs on the wall, it emerges as strongly as the indentations in the street. Like a flat-screen, behind which our common daily history functions as an apparatus for the production of images. I have worked on it since 2012 and have collected castings from various cities worldwide.

On the occasion of documenta 14 you are exhibiting a work consisting of smoke, seemingly a product of ignition in the tower of the Fridericianum. How does this installation fit into your artistic practice?

As with my earlier works, Expiration Movement is also the materialization of a concept. The work is about the representation of the expression of a social moment, in which we find ourselves: the moment of expiration and of transience. It is my intention to describe the satiation of colonialism as a phenomenon of our time, as the impossibility to further inhale, capture, and occupy. The result is expiration, release, and change. The duration of the "smoke performance" corresponds to the duration of the exhibition. Since April 8, 2017, the day of the opening of documenta 14 Athens, the Zwehrenturm has been emitting smoke during the opening hours of the exhibition.

Smoke is not easy to grasp, it is visible from afar and suggests a threat, yet at the same time, it has an esthetic quality. What drew you to this material and this location?

Smoke is evidence of existence and is one of the earliest means of communication. It is a collection of airborne materials that change, stream, and represent activity. At the same time, it has many historical connotations. Kassel’s Friedrichsplatz is a place, where book burnings took place. After the bombing raids of World War II the walls of the Fridericianum lay in smoking ruins. Many are reminded of papal elections. And indeed, in 1945 the Rothwesten conclave was held here, where American and German finance experts decided the currency reform for the German Mark in a non-public meeting.

For the first time, this year the documenta is also held in Athens. You are one of the few artists, who are represented with works at both venues. Do your works correspond with each other?

It was my intention to create a corresponding and financial connection between my works in Athens and Kassel. In Athens I showed and created books containing objects I found in the street, this act is in itself, a kind of contemporary archeology. The books are sold both in Kassel and Athens and the proceeds finance the smoke in Kassel. I was interested in creating a circular flow that challenges hermetic archeology through the act of collecting in the streets of Athens. Furthermore, I wanted this collection and the documentation of a contemporary moment to flow into an edition, I wanted it to be consumed and to rise as smoke. As expiration, consummation, and spending Expiration Movement represents an antithesis to collecting and preserving

In the past you have worked together with Adam Szymczyk, the artistic director of this year’s documenta. What do you think of his curatorial concept?

Adam is one of the best curators I know. His concept is that of an open network. Like entering a train of thought, he engages with every artist he finds interesting and accompanies him or her for a while. His way of curating is unique, because it compares to an artistic practice. He supports new concepts and marginal positions, discovers new possibilities of perceptions. In doing so he does not follow the trends of the art world, but he creates new paths. An exhibition is a kind of code. We understand even more if we try to decode him. Sometimes concepts are so complex that it takes time to understand an exhibition – just like an artwork.

One hears time and again that artists have difficulties in getting their documenta contributions financed. What happened with your quite elaborate installation? Do you consider your participation as an investment in the greater visibility of your work?

It was a great effort to develop the concept, but it was the only work in which Adam "stepped in". I have carried the idea in me for quite some time. Here the right context had been found. Therefore I did not understand it as an investment. Honestly, I actually never do that. For me the idea and the context count, the realization follows later. The documenta is a larger project and every edition has a different financial concept. It was interesting to me to immerse myself in this context and to enforce my way of working. It is to Adam’s and the organization of documenta 14’s great credit.

Interview: Michael Wuerges

Photos: Florian Langhammer