Daniel Moldoveanu does not seek answers in popular formats and trends. Instead, the former dancer and fashion school student turned artist, constructs two-dimensional wallpaper-imitating paintings and transforms pre-existing images and narratives into statements about hollowness, sexuality and a sense of mundanity in people's lives. Superficiality hides depth, thinks Moldoveanu. To fully understand what lies beneath his layers, you literally have to take a closer look at his work.

Daniel, you were born in Constanta, Romania, a beach town on the Black Sea coast. Were there any indications that you would become an artist in the future?

As with my life subsequently, my childhood was driven by three main impulses: ambition, delusion, and audacity. In Constanta, there is one art museum that I visited regularly. I frequented various workshops there. There was also a children’s book club in the local library, of which I was the only member. At home, I used to put on self-staged dance performances and dress up as Marie Antoinette walking around the house in anticipation of being guillotined in the midst of an imagined revolution. I decided to leave Constanta because of dancing. My ultimate goal was to become a choreographer, so I auditioned for the Vienna State Opera Ballet School and was accepted.

What was your experience studying there like?

Unfortunately, that institution turned out to be kind of brutal, nor did it provide the choreographical education I had envisioned. As a result, I ultimately decided that pursuing fine art would offer peak freedom and creativity, at least in theory. After trying one or two more schools, I enrolled at the Fashion Institute of Vienna for a five-year course with a focus on tailoring and fashion design. I had also begun interning at the age of 14 and in addition, hustled all kinds of jobs on the side; most of which were art related.

How did you decide to move from Vienna to Berlin and find a place on the Berlin art scene?

By the time I had moved here, having decided to pursue Cultural Studies and Art History at Humboldt University, and having also applied for the Fine Arts program at the University of Arts, I had already been in active contact with a number of curators and writers and people I was affiliated with in Vienna’s art scene. I’ve always sustained that social-gaming parallel to my education. I think Vienna and Berlin are quite interconnected, although I have to say the scenes differ quite a lot. Berlin is vast and scattered… there’s a feeling of there being so-called stakes. Vienna’s scene is more comfortable, sometimes too much so.

What opportunities did Berlin open for you as an artist and what challenges did you face?

I moved here because I had a sort of historically informed, culturally conditioned fantasy of Berlin as the pinnacle of debauchery – I didn’t necessarily include the art scene as being part of that because I thought the art scene was part of that. I moved here because I felt inspired by the city’s legacy, and the nightlife and the chaos of it all. Very Eyes Wide Shut. I didn’t come here chasing my career again. I knew that if I felt happy, I would feel inspired, and if I were to feel inspired, that should in turn, revert to a state of productivity. As for challenges, honestly, everything feels unnecessarily complicated in this city. But you get used to it, the rough edges, and with every successfully completed errand you gasp with a sense of having been victorious.

What do we need to know about your art?

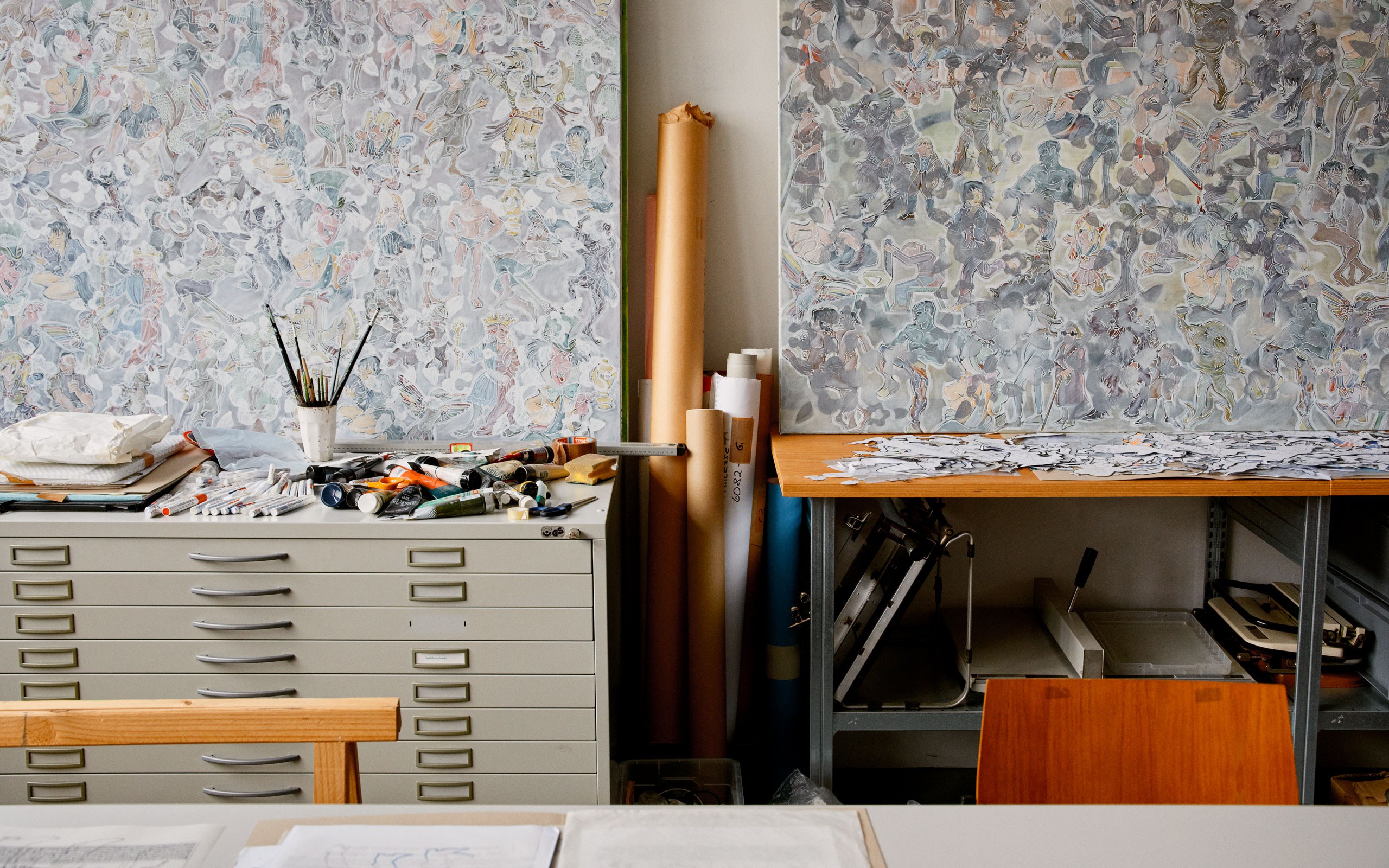

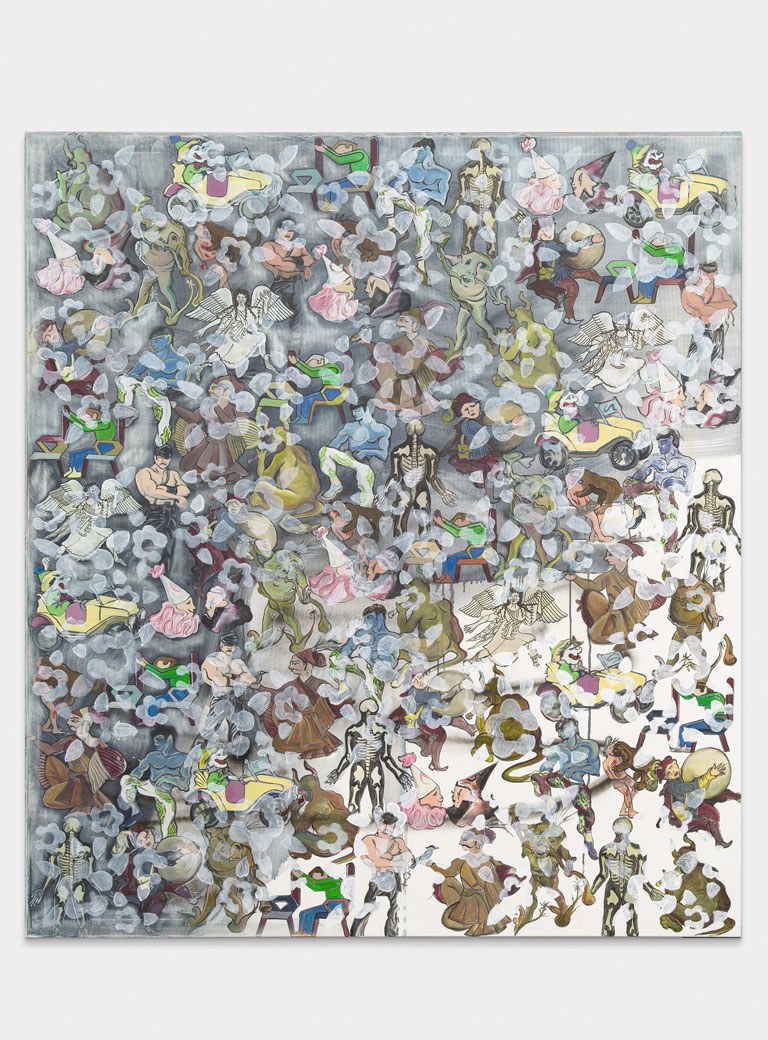

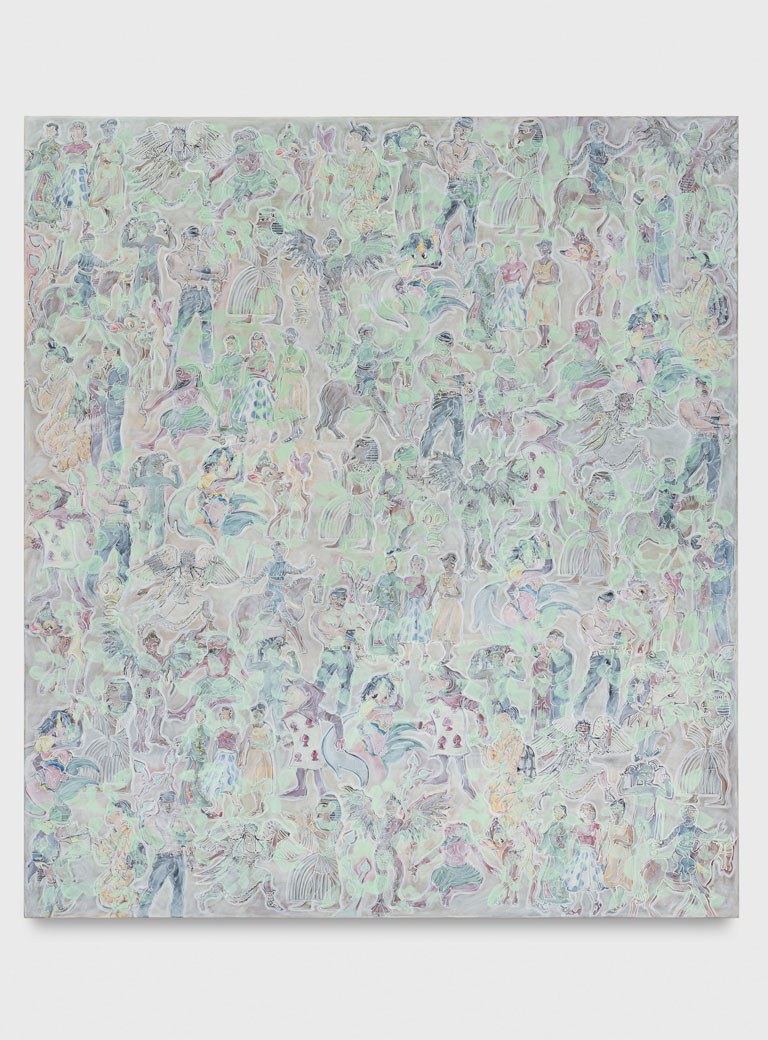

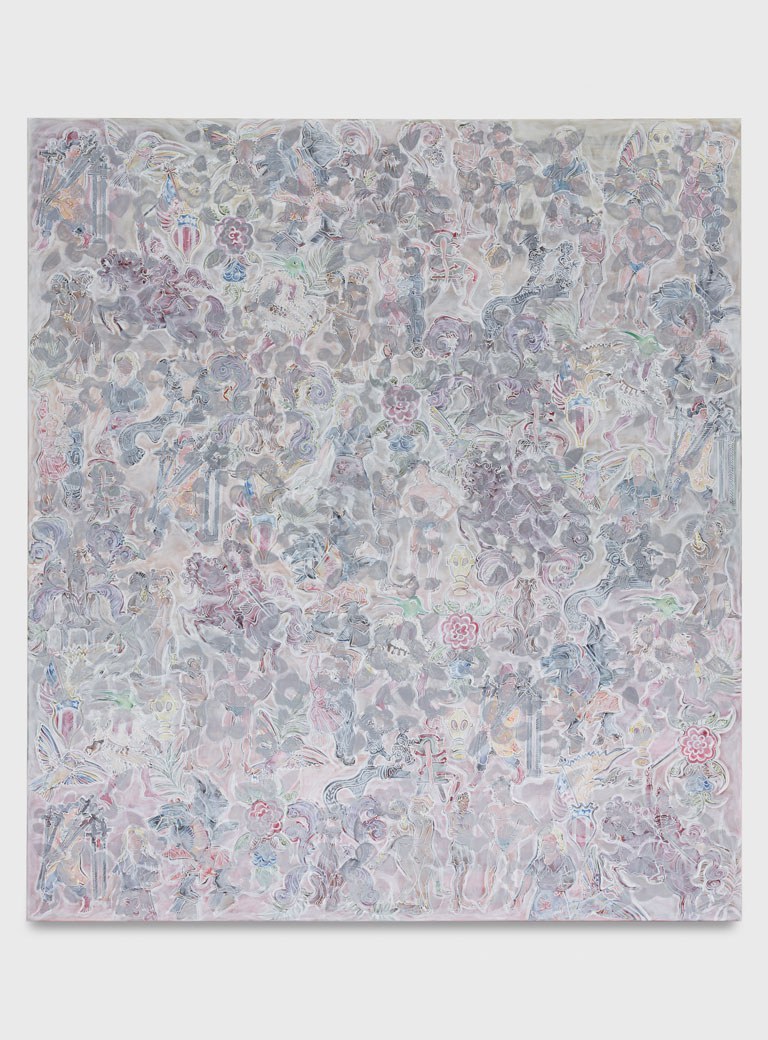

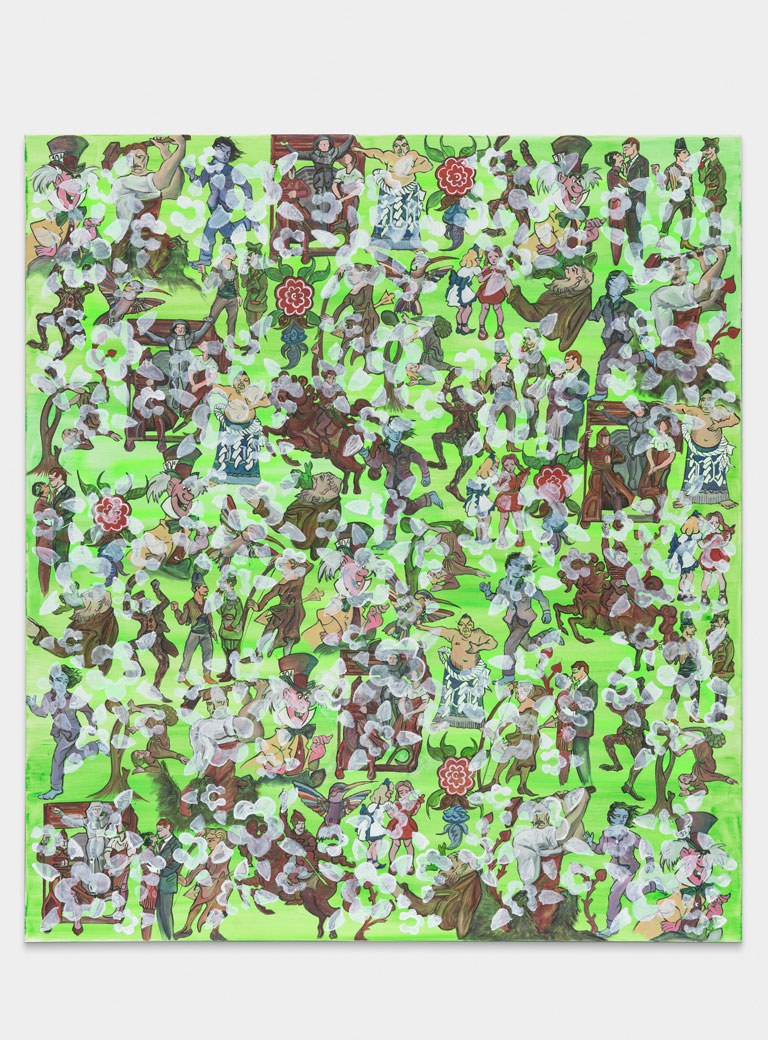

My whole practice is based on a kind of obsession with flat, figurative painting history. I extrapolate from it and then use my findings as raw material to discuss its echoes in the canon of postmodernist theory, of poststructuralism, specifically in the vein of media and aesthetic philosophy. There is a lot of analogue painting, an interest in replication, imitation, repetition, difference, the illusion of patterns, the lack of a system. I like naivety, or the appearance of it, and I elevate privilege concept over form. It’s kind of psychedelic and maximalist agglomeration, there’s a lot of layering with thin coats of white paint and correction pen. A lot of my paintings are also about the tension that arises when you lack a certain feeling of canvas ‘space.’ I constantly try to show that nothing is ever the same, that nothing fits like a glove, that certain truths are as beautiful as they are frustrating, that nothing about aesthetics or idiom is intrinsic to one meaning over another.

Typically, a correction pen is used to cover up mistakes. What is your reason for choosing it?

The reasoning becomes one with the process of painting itself, homogenising the individual motifs in a manner that makes them very hard to tell apart at first glance, like a blanket of snow. In that sense, it serves the purpose of concealment. It was also the whitest thing I could find available when I started painting in my boarding school room. These modular or serial canvases of mine essentially will themselves direct ambition into architectural structures. I like to install them in a way that imitates walls and partitions, or this kind of construction of spatiality that is simultaneously imposing and self-consciously hollow-looking or provisory, frail. I like the idea of outsider art, of Henri Rousseau obsessively painting the jungle without ever having visited one.

Where does this engagement with outsider art come from?

I never really received any formal art education, not even during my time in the University of Arts. By the time of my enrolment, my practice was already well defined. I come from a self-taught background and that informed a lot of what I do and how I do it. I also like the idea of deceiving audiences by presenting them with something that can be easily discarded as simply ornamental.

Your works are often layered with elements of queer life or pop culture. For example, images of Britney Spears, Lindsay Lohan, and Paris Hilton at their scandalous parties. Some artists try to distance themselves from pop culture. What role does it play in your artistic work and how does pop culture influence your creative choices?

Firstly, I don’t distinguish between art and non-art. To me, everything is equal as material of human expression, be it meaningful or meaningless. I think that expression finds or holds legitimacy in absolutely every form in which it takes shape. Of course, popular culture is a product of capitalism and is more readily ‘consumable’ than niche stuff… but we consume everything today, material or immaterial, people, moments. To me, the boundary between popular culture, underground, or what is considered ‘niche’ is not that clear because I’m not looking at it from an empirical perspective of: “What is the size of the audience?” In that sense, I’m not a numbers girl. It’s all just… stuff, as the enraged Miranda Priestly in the film from The Devil Wears Prada would say: a pile of stuff. At the same time, the history of two-dimensional figurative painting is, in a sense, a history of pop culture. Hieroglyphs are the popular culture of Egyptian antiquity, like utilised iconography destined for a proverbial mediation. It entails a precise relationship between signifiers and the signified. ‘Flatness,’ aesthetical and metaphysical, is fundamental to cohesion, to narrative building, to image making, to organizing, to constructing.

In your essays you combine discussions of art history, philosophy, sociology, and global politics with your experiences of Berlin raves or with a review of the final scene of The White Lotus. Should your writing be considered as a part of your art practice?

To be honest, I feel like my whole existence is one big, round, giant ball whose purpose is to generate meaning. I haven’t always wanted to ‘professionalise’ myself as an artist. It happened because freedom became the sole reason for my being. But then, I wanted to be able to sustain myself while living not a, but that, meaningful life. I wouldn’t separate my writing practice from anything else that I do. Whether I paint, write, go clubbing, argue with someone, crack jokes, my brain just continues working on a singular developing source of fluid meaning. When I have an existential dilemma, or a depressive episode, I usually stop everything at once because each thing echoes the other. One thing cannot substitute the other. A lot of my writing and my interests in studying culture stems from having an existential battle with the meaning of ‘superficial,’ mostly because superficial is often considered to connotate a lack of meaning, or an inconsequentiality of it. Yet everything today is superficial, in one way or the other, and it is also profoundly meaningful. That’s also where my self-prescribed ‘Intellectual Bimbo’ identity comes from. I like the idea of being true to myself and a caricature to others.

The influence of your fashion education is apparent in your other artwork featuring coats with prints, which appear distinct from your paintings. Could you tell more about this project?

For my fashion diploma I designed digitally printed garments that take a sculptural form, later using them as costumes for a series of portraits. Nothing about that is particularly innovative, but this play of imagery and optics and surface-building was different for me, as a painter. I wanted to dress bodies in distorted, commodified images of other bodies, and talk about the art of pattern making in a literal and figurative sense.

Was your goal to create some sort of camouflage?

These costumes acted as a camouflage and sort of imbued the main characters of my portraits with the background of where they were photographed. One was done in an Orthodox Romanian church in Vienna, and the model was wearing overalls printed with a photo collage of naked bodies. We shot it upstairs while downstairs, a baptism was taking place. Another was shot in front of a socialist public art mural, and another in Kaiserbründl, a historic ‘orientalist’ men-only sauna in the centre of town. I used some of the earlier shots and combined them with other images for further prints, making further costumes. Similar to how I layer and weave paintings with a correction pen, I wanted to obfuscate the immediate visual difference between a background and a foreground, between subject and object, body and space etc. by agglomerating and assimilating shapes. I do think that this kind of sensibility towards garment or costume making will sustain relevance to future projects. I recently had to think of one in an essay I once wrote about the joker figures, and scams of culture, titled The Ethical Scammer. It came to me that I should make costumes based on Jan Matejko’s painting Stańczyk, which I had insisted on using as a header image. It’s a beautiful painting.

Will any of your upcoming exhibitions feature any of these artworks?

Hard to tell. I have an upcoming solo show at Grotto, a new Berlin off-space curated by Leonie Herweg. This exhibition takes Edwin Abbott’s 19th century novella Flatland as a starting point. In addition to paintings, drawing and prints, I’m also working on a video essay about the relationship between theology and iconography, belief, and semiotics… which is also what the book is about, to a certain extent. The novel makes the case that science shouldn’t discredit the merit of believing in phenomena it cannot account for. We find ourselves in a polarised world where people truly inhabit different realities, holding sway over apparently differing sets of facts. The underlying current is heavily ideological. In times like these, challenging our own beliefs from a place of humility or seeking something greater than our own opinion, could go a long way. Another solo exhibition is set at Invitro Gallery in Bucharest, a non-profit space founded by Tudor and Genina Grecu. That one should be happening in the autumn. I was thinking of connecting that project to the book I’m currently working on having published, The Intellectual Bimbo Manifesto.

How does it feel to be back in Romania, even if only temporarily and for work?

Having moved out of home when I was 11, I naturally have a very limited scope of understanding of the current local atmosphere. I’m a bit of an outsider, but that applies to wherever I live, and I prefer to keep it that way. It’s always interesting to experience another scene that is fundamentally different. One of the things that surprised me the most is that people in Romania still talk about, and are actively engaged in debate about, art, when they go to art-related public social events.

Is it much different than Vienna and Berlin?

In Vienna or Berlin, the social practice of attending art openings has come to be a pretext for talking about anything other than the art itself; except for when it’s a lecture or some carefully curated panel discussion where everyone pretty much holds the same position. In Berlin, the guns are normally pulled out over dinners, because that’s where people feel put on the spot with a ‘selected’ crowd – and they feel like they have to have an opinion, they have to make a point, to prove themselves. They usually do that by saying something slightly different but not really controversial, some pseudo-dissident ‘but.’ Everyone just talks the talk and forge alliances over the blandest topics imaginable, and I have yet to witness a serious, organically developed debate; whereas in Romania, I had the feeling that people go all out. Maybe even without resentment, but that one’s always hard to tell… I’ve honestly had my most inspiring, artful encounters with people completely unrelated to art, which only strengthens my belief that creative expression should have never been institutionalised.

As you mentioned earlier, your experience at the ballet school was quite oppressive. Have you attained a sense of complete freedom as an artist?

I feel like I really have my own little discourse going on. Maybe that’s because I still consider myself an individualist, a humanist, which is an asphyxiated philosophy at the moment. I’m not finding much solace in people’s current hot takes. I’ve always done my own thing and, when pitching essays for example, insisted on my own topics and their reasoning. If they were accepted: fine; and if not, then they were not. Why do editorial guidelines exist? Isn’t it nice when readers are positively taken aback by something they hadn’t expected to read? My art practice always seemed highly inefficient to me, increasingly more so as it advances. I want to trot the globe but insist on amassing a huge number of canvases twice my body size. But I do it because it gives me meaning and that’s pretty much about it. As one observer described Gabriele D’Annunzio’s breakaway occupation of Fiume in 1920: “Songs, dances, rockets, fireworks, speeches. Eloquence! Eloquence! Eloquence!” – even if that’s just in my own head.

Daniel Moldoveanu, Untitled, 2023; Acrylic, correction pen, white marker on canvas, 180 x 160 x 1,8 cm; Image: Courtesy of the artist

Daniel Moldoveanu, Untitled Wallpaper (mint green), 2022; Acrylic, correction pen, white marker on canvas, 180 x 160 x 1.8 cm; Image: Marjorie Brunet Plaza

Daniel Moldoveanu, Untitled (shades of gray), 2023; Acrylic, correction pen, white marker on canvas, 180 x 160 x 1.8 cm; Image: Marjorie Brunet Plaza

Daniel Moldoveanu, Untitled Wallpaper (neon green), 2023; Acrylic, correction paste on canvas, 180 x 160 x 1.8 cm; Image: Benjamin Marvin

Interview: Anton Isiukov

Photos: Patrick Desbrosses