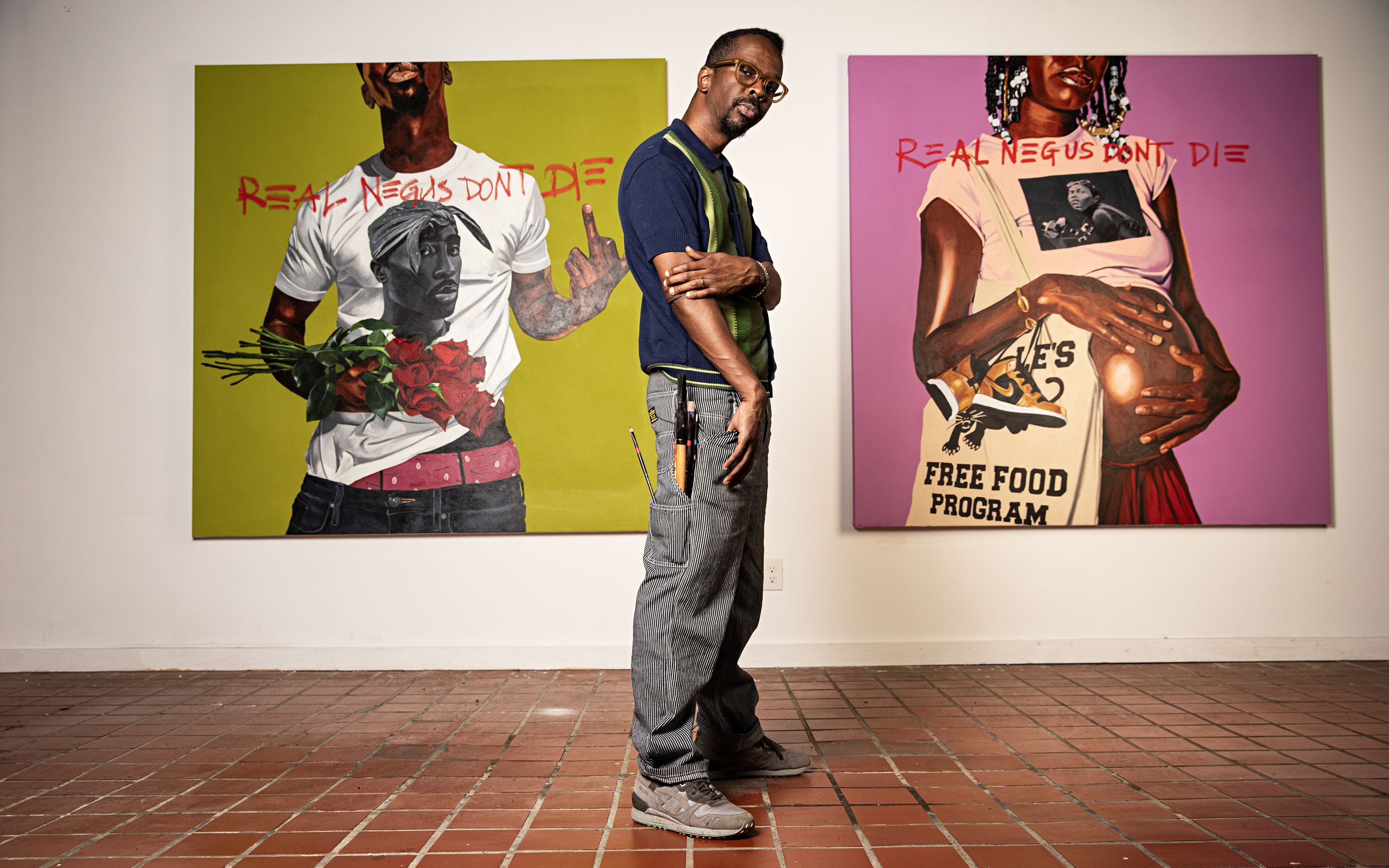

Dr. Fahamu Pecou is an American artist and scholar working in painting and performance, drawing from his observations on hip-hop, popular culture and fine arts. His artistic and academic work deals with the contemporary representation of Black masculinity, and how the stereotypes created by images relating to Black men shape and impact our understanding. He is the founding director of the African Diaspora Art Museum of Atlanta (ADAMA) and holds the title of a French Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres.

Fahamu, why did you want to become an artist?

I don’t recall ever not having a pencil in my hand from the time I was four or five years old. Instead of taking notes at school, I was drawing cartoons. I would even bite sandwiches into the shapes of animals (laughs)! I was in choirs, rap groups, dancing, playing trombone in the school band – loving creative expression in any form. But I don’t truly know where my creativity comes from. Where I grew up, there was no such thing as a museum or a gallery, I did not really experience “art” before I went to college.

Is this why animation was your first interest?

I wanted to be the Black Walt Disney! When I was nine years old, I told people that I wanted to be an artist, and everybody said that I would just be starving… but I figured out that a cartoonist could make money. So, from the age of nine until I went to college, I prepared myself to become just that. I made my own cartoons, copied them in the school library and sold them for 50 cents.

But that changed once you went to the Atlanta College of Art?

I wanted to major in animation, but then I met a girl who showed me museums, galleries, pointing out styles, art movements and materials. I developed a passion for painting. So instead of drawing cartoons and coloring them, I started to paint these cartoon characters, and changed my major from animation to painting.

How did you start out as a painter?

After graduating with a degree in painting, you can’t really apply for a job! So, I lied on applications and said I did graphic design, at least I knew how to use the software (laughs). I started working at this small advertising company, doing media for hip-hop artists: album covers, flyers etc. This gave me a unique opportunity to sit down with the rappers. I was taken aback – they were not at all like the person they played on TV! It was just marketing. So, I wondered what would happen if I marketed a visual artist, myself, the same way I would a rap artist.

Because they were so visible, as opposed to Black visual artists?

Yes, I was miffed by the fact that a Black person could be popular as an entertainer, but not as a painter. I thought about how to get that level of success and visibility for my kind of work. So, I came up with this project: #FahamuPecouisTheShit. In the beginning it was a joke. It did not specify what I did, there were just posters that I would paste all over Atlanta. They were illustrations of me, no shirt on, looking real tough like a rapper, and on the bottom the line: “Paid for by The Committee to make Fahamu Pecou Officially The Shit”. I was just curious to see what would happen! And it was an immediate success because people instantly wondered “Who is this guy?”. Even though there was no relation between the art I made and the campaign.

From today’s perspective, you could say that you were staging a performance that says quite a bit about the art world!

I was moved by the fact that as a Black visual artist, you existed in an ambiguous space. The art world was not quite receptive of us in the late 90s and early 2000s – so as a Black artist it was a weird space to be in. I was figuring out how to break beyond it.

How did you use that performance to become a serious painter?

Well, that came from my obsession with magazines. After two years of doing the Fahamu Pecou is The Shit thing, I am in the bookstore, and a subscription card fell out of a magazine I was holding – a preview with somebody I did not know on the cover. But that somebody had to be important to be on the cover, right? That got me thinking: “Hm, I should be on the cover of a magazine.”

So you put yourself there?

I had this picture that a friend had taken of me, then I designed a cover for a made-up magazine called Contemporaneo. Then I printed subscription cards saying the first edition would be free for whoever sent the card back; and inserted them in all the magazines in bookstores all over the city. These cards came back by the hundreds: I was blown away (laughs)! And then I thought: “Hm, I should paint this cover.”

And that was the start of your career as a painter?

Yes. I made a painting of that fake magazine cover, and the angels started singing, the clouds started parting. This was the direction to go. I was putting all these preconceived ideas about Black men into the character I was performing as. And I turned them around by putting this character on an art platform, painting him on the covers of magazines like Art in America, Artforum and such. And I think that this made the work powerful, because it caused people to question their preconceived ideas.

Why is the theme of Black masculinity so important to you?

It’s about the notion of being a Black man. I observed the obsession society had with Black male rap celebrities. A lot of this conversation was stereotypical. From early on I observed how people saw me and treated me, because often it did not match with the perception I had of myself. People did not see Fahamu, but a Black man. Their view had been shaped by media and stereotypes, and they treated me the way they had been conditioned to think about Black men. It had nothing to do with me.

Are these preconceptions hard to overcome?

Very much. And that is why I think that many Black men, as opposed to trying to push against them, fall into these stereotypes. It feels safe and comfortable.

So Black men, and especially Black artists need role models. Do you consider yourself as such?

Wow, I take great pride in that. When I was young, there were no role models. But there was this TV show, Good Times, about an African American family living in a housing project in Chicago; the character J.J. was a painter. It was the first time I saw a Black male artist, he was the only Black artist I had ever heard of before going to college. That experience of seeing his work changed my life, gave me a focus. I can only hope to have that kind of impact.

You must have been quite self-confident to pull the Fahamu Pecou is The Shit thing off. Does an artist need to be brave, put himself out there?

I think so. The one consistent truth about being an artist is that your brand, your work, your aesthetic has to be as unique and as original as you are. You have to be willing to go someplace nobody else is willing to go. There are so many times where we see somebody being successful and we want to replicate that thing, because we can see that it works. But when they talk about the beaten path – the beaten path is beaten for a reason! Everybody has been there. To discover something new, you have to get off that path. It can be scary, treacherous, you might make mistakes, but ultimately you will get to a place that is uncharted, a place that makes you stand out from the crowd.

In your work, you like to use juxtapositions: traditional decorum and Air Jordans in the same painting, for instance. Why put it together?

What I am interested in is to complicate the image of Black people. We have these fixed ideas about people based on their identity, their body, their skin color. But that is not all they are. I try to complicate that visual narrative and to expand people’s perceptions. Not only for the people who look from the outside in, but also for the people living inside these bodies.

Does your art resonate with people who are not Black as well?

Certainly! When I had my first show in Paris in 2011, I was concerned that a European audience might not get it. But the response was overwhelming. People were able to identify, relate to and even name and place the little inside jokes I put into my paintings. This French guy, who barely spoke English, came up to me to tell me that he had recognized a line from a De La Soul album – I was blown away (laughs).

Your work is going to be shown in Vienna soon, as part of the exhibition Avant Garde and Liberation at the MUMOK museum. The painting in question is A.W.N. (Artist with Negritude). Could you tell me about the juxtaposition in this work – and “négritude”?

A.W.N. is the inverse of N.W.A. (aka Niggaz With Attitude). N.W.A. is infamous for ushering in the era of what is known as gangsta rap. Despite the original sociopolitical intent of the group, their brand was co-opted and used to help perpetuate violent and dehumanizing stereotypes about Black men. A.W.N. (Artist with Negritude) transposes the negative ideas associated with Black men and looks to empower our ideas and presence. Negritude, which remains a critical intellectual and artistic movement for Black subjectivity, becomes a way of denouncing the harmful images and creating new ones.

Is your focus on Black masculinity not limiting the reception of your work?

In doing that thing that makes you uniquely yourself and separates you from the rest of the group, you create a space for other people to see their own value and uniqueness. That is the real jewel. Yes, I was concerned that my hyperfocus on Black masculinity would limit me. But ultimately the conversation I was having was the one we are all wrestling with: Who am I? What value do I bring to the world? Whatever racial, sexual, national, spiritual, cultural identity – we all struggle with this same question. In making it personal, it becomes universal.

Art serving as a connection?

Yes, art especially brings us together in a conversation. That is why I think art is so important. It is in fact a language, that defies and supersedes our spoken tongue. There is a saying: “In the future historians will say what happened, but artists will say how it felt.”

You are mentioning “art as a language”, that brings me to your academic career. You have a PhD degree, you are holding lectures… Was “just” being a painter not enough?

(laughs). It was just a natural organic evolution of my practice. When I made my paintings of magazine covers, people would say: “Your work is in conversation with bell hooks (American author and theorist), or Henry Louis Gates (American professor and historian).” So, I read these books, and my practice over the years became very research based.

Meaning you start every painting with a concept?

Yes, and when I have the concept, I try to find out as much information as I can around that subject, get as many perspectives as possible, to enhance what I want to say through the work.

How did your academic career transform your practice?

The practice of academic writing was an unexpected gift. My early works are dense with text and information. The PhD program at Emory University started helping me distill my ideas, to work through everything I want to say and whittle down the visual to the most essential. It’s about creating a space for my audience instead of bombarding them with information.

Is your work as much a statement as your academic writing?

I approach my work as a series of questions. It’s never a statement, it’s never a declaration. I am asking myself questions, the work is ultimately asking questions, and I want to leave my viewer with questions.

Should Black Art be propaganda?

I think it always is. It’s inherent propaganda. On some levels, our art is advocating for our humanity.

But isn’t any art?

Any art is, certainly. But I think that in the course of the history of what we know of as art, we can account for 400 years at least where Black people, particularly in America, did not have the privilege of being able to make art about their experience. While our white counterparts could make art about anything – it does not have to about humanity anymore, it can be about experimenting with colors or such – we don’t necessarily get the same privilege. I think that so much of the art that Black people are making, especially now as more and more Black artists become seen, is about reorienting the expectations or perceptions people have about Black identity.

Don’t you feel that boxes Black artists in?

I can’t speak for every Black artist, but I don’t feel boxed in. I feel that it is a privilege, an obligation, I feel a sense of responsibility to use my talent, my gifts, my ideas. To use my position as an image-maker to make sure that whatever is being said in my work affirms the humanity of people who look like me.

When growing up, did you have the feeling of having only limited options?

Definitely. My entire childhood, teachers, media, everyone asserted that as a Black man I was more likely to end up dead than in college, less likely than my white counterparts to live past 25, more likely to end up in prison… The power of these images and ideas profoundly impacts who we think we are.

Why do you think there might have been a danger for you to turn into that stereotype?

I grew up very poor in the ghetto in South Carolina. The apparent choices were extremely limited. You either went to work in a factory, you sold drugs or you were dead or in jail. For me to say that I wanted to be an artist… I was a unicorn. Nothing in my environment pointed that that could ever be a possibility. But I knew: as soon as I could get out of there, I would – and there would be no coming back.

You must have been very focused – what about your friends?

Some got out, but not many. What gets rarely discussed in our culture is the mental health of young Black males. You are bombarded with the notion of your impending doom. Around the age of 10, people cease to see you as a child, your family wants to protect you by making you tough. The outside world looks at you with contempt and fear. Television and movies and magazines portray people that look like you in varying states of death or dying. When I came to Atlanta, I had no money, I worked to stay afloat. At this point, I got depressed and my grades started to slip.

How did you find the strength to go on?

A part of it was art. But I was lucky, I enrolled in a painting class and met my mentor, Arturo Lindsay. As much as I credit Arturo with redirecting me, it wasn’t an easy thing. I was jaded, angry at the world. Arturo being a man of color, he saw through me, through the shit that I was trying to pull. He did not let me stomp off, he checked me, pushed me, challenged me. He would always admonish me saying “There is no such thing as luck. You have to be prepared when your opportunities come” or “Do it right the first time and you don’t have to do it again”.

How do you reciprocate that now as father of a young Black boy?

That is why my work is focused on Black men. I want to have this conversation – not only for myself – because I did not grow up with a father. I needed to learn how to be a better man, to see myself beyond what the world was projecting on to me, so that my son could see that he is not limited, either. All of my sons, all young Black men… My work is about building a sense of responsibility and purpose, I want to use my power for the good of my community.

Being a father to all, because you experienced growing up without one?

My father suffered from mental illness, schizophrenia. He murdered my mum when I was 4 years old, in my presence and that of my siblings. He spent pretty much the rest of his life in a mental institution. But I made peace with it. During the last years of his life, we developed a relationship.

Did you ever use this horrible trauma in your work?

Yes. I remember on my first day of class at the Atlanta College of Art, the professor wrote on the board: “What is art?” – and I had never even thought about it before. But none of the answers people gave was substantial enough. It stayed in the back of my head all these years… In my junior year, when I was 20 years old, I gathered with my siblings for Thanksgiving. We had never talked about the thing with our parents. I asked my siblings to write down what they remembered from the night our mum died. These perspectives painted a vivid picture of my parents, of the incident.

And you used these accounts?

Throughout my senior year, I used them to create a body of work that became my senior thesis exhibition. It was installed in a gallery, and the people who came were moved, in tears. When I watched people react and interact with my work, I thought: “This is art!”

Would you say that art has turned your life around?

Absolutely. Inside out, upside down, all of that.

What are your next projects?

My show with Conduit Gallery in Texas just finished, and there will be a new show in Paris in September 2024 with Backslash Gallery. I am also working together on a project with my cousin Thierry Pecou, a celebrated French composer and musician.

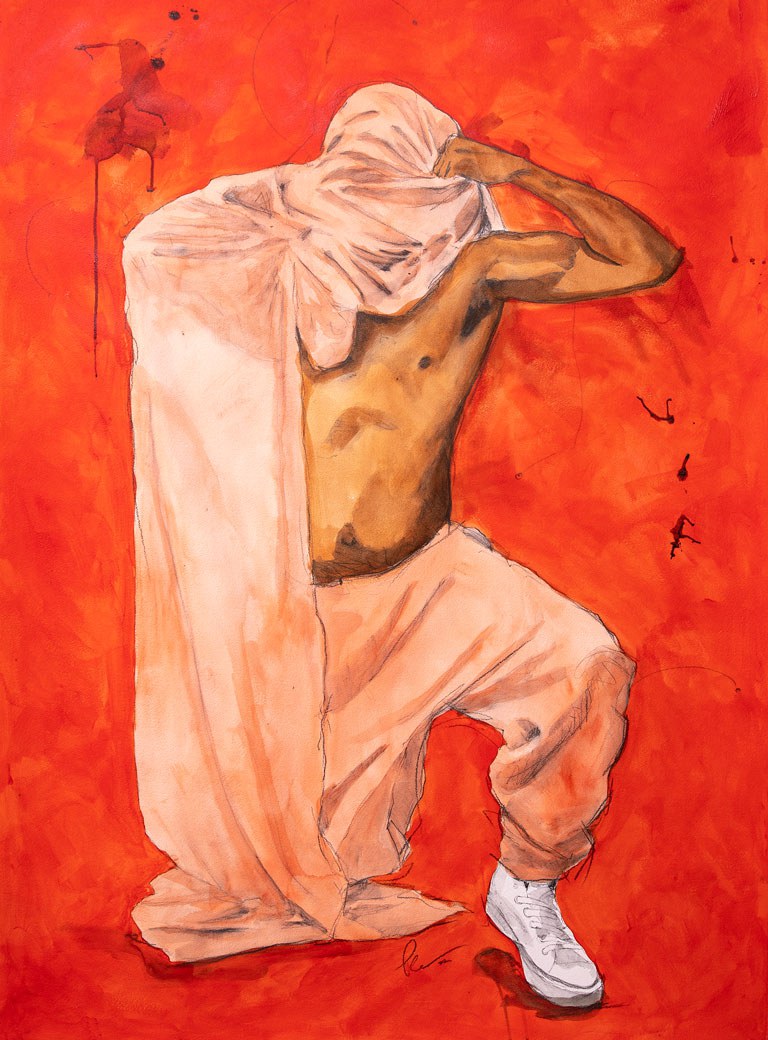

End of Safety: Compliance, Graphite and Acrylic on Paper, 60 x 40 in , C. 2022

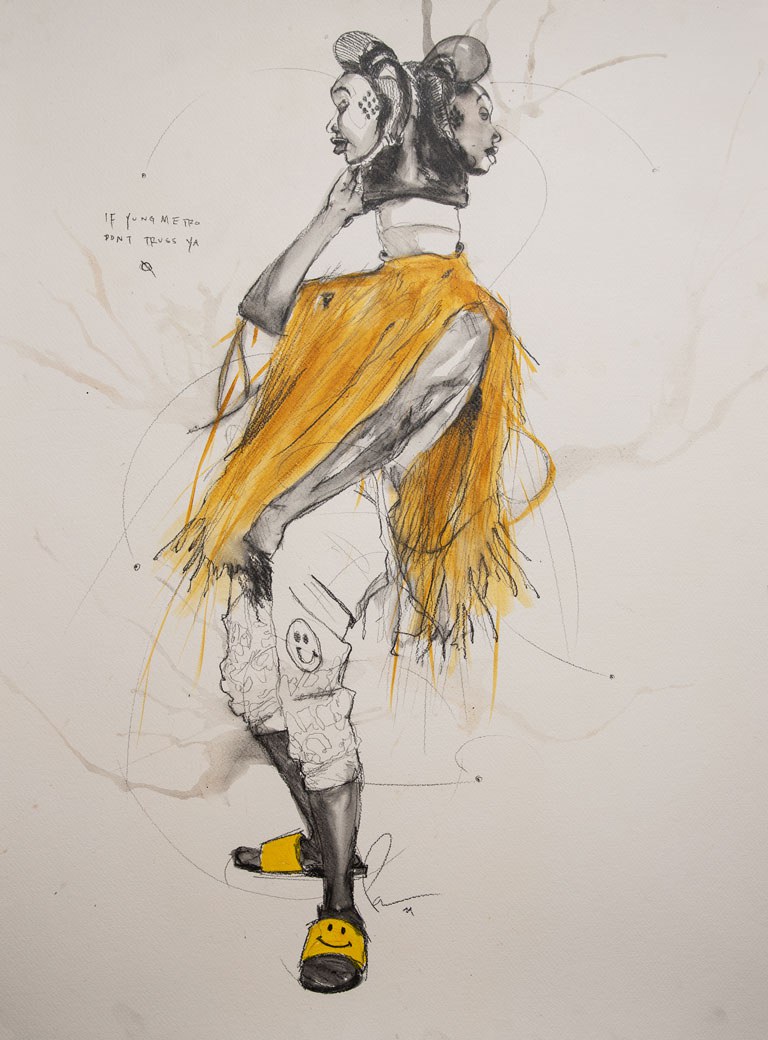

If Young Metro Don't Trust You, Graphite and Acrylic on Paper, 30 x 22 in, C. 2021

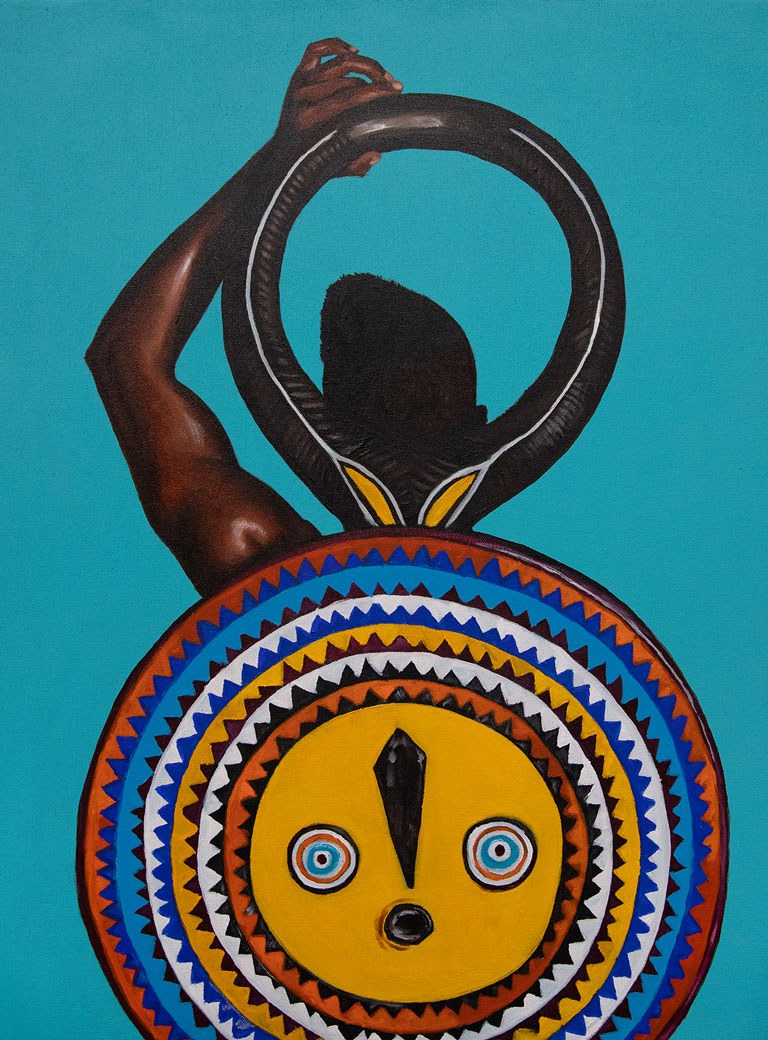

Rise, Acrylic on canvas, 24 x 20 in, C. 2023

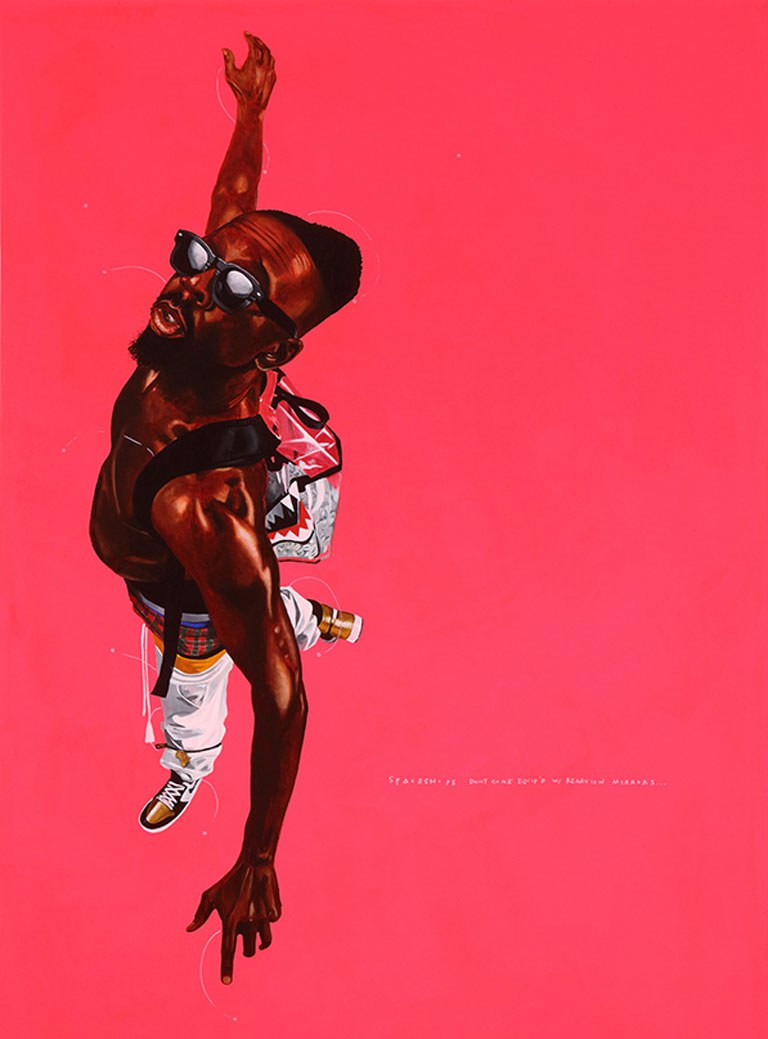

Spaceships Don't Come Equipped with Rearview Mirrors, Acrylic on canvas, 72 x 48 in, C. 2023

Interview: Alexandra Markl

Photos: Terra Coles