The scene for contemporary art in Europe’s North is expanding and developing new dynamics as international collectors are watching the scene. With Nordic Notes we regularly cast the eye on the Nordic art and cultural scene, portraying its important actors.

Most video works by Finnish visual artist Eija-Liisa Ahtila take place on multiple screens, producing different vantage points of a story simultaneously. She intentionally floods or overwhelms the viewer's senses in order to produce a strong emotional impact. Instead of following the traditional moving image script, Ahtila explores and innovates on modes of presenting a state of mind or other condition. After having explored the interior world of her human protagonists she has more recently moved to developing less human-centered views of the world. In times of severe human-made situations of crisis, Eija-Liisa Ahtila’s dramaturgic statements could not be more compelling.

Eija-Liisa, you are often referred to as a “filmmaker” and “video artist”. Is this how you see yourself?

It is true that I attended film school. But I think my approach is very much one of a visual artist. Instead of thinking along the lines of a certain length, a particular audience, or other parameters, I am more preoccupied with the medium itself and the implied artistic approach. I am questioning what can be done with moving image, and what characterizes this specific medium.

How did you arrive at dealing with “film”?

When I was in school my favorite topics weren’t really the subjects that had to do with visuals, but essay writing in Finnish class. My grandfather was a great storyteller. He must have passed his passion for stories on to me. I’m able to write fast and when I get excited it just flows. I discovered film because, as a medium, it responds to the human senses. It allows the combination of writing and storytelling with visuals as well as sound, rhythm, location, acting, etc. Moving image also presents itself as the language of our global culture.

You studied film at UCLA (University of California, Los Angeles), which is a part of the “dream factory” of Hollywood. How did the education you received there impact on the way you feel about film today?

In the beginning it helped me acquire the skills of scripting and developing a clear narrative structure of a conventional feature film. It not only taught me how to pull ideas together, but it also helped me break these ideas apart again.

What attracts you about moving image?

The whole mechanism of the moving image has become very powerful. The moving image has become the most popular means of representing our surroundings and society. It has become our central medium of presenting the world. But to the same degree the medium shows the world to us, it hides other parts. A specific perspective and a particular version of looking at the world are imposed. It is inevitable to ask: Who should be allowed to perform in this image of our world that we create? Who can be a protagonist? To whom/what do we grant the status of an actor?

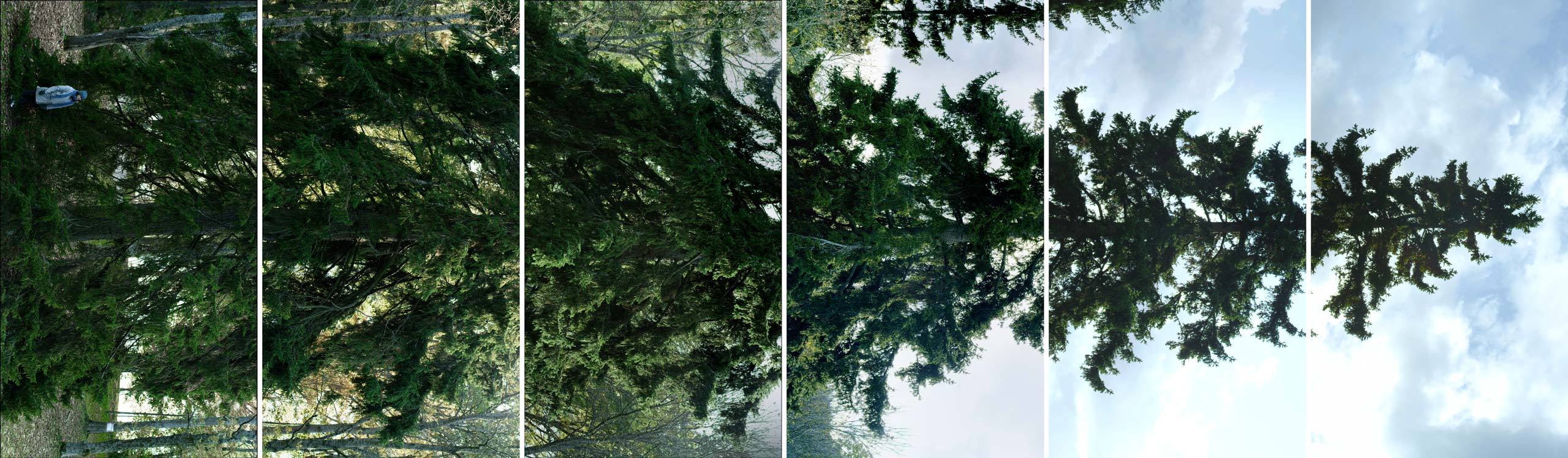

Studies on the Ecology of Drama, 2014, film still, Courtesy Crystal Eye / Malla Hukkanen

Studies on the Ecology of Drama, 2014, film still, Courtesy Crystal Eye / Malla Hukkanen

How does your filmographic oeuvre fit into this context?

I am trying to stretch the idea of what a moving image should be like, and how stories are told, or could be told. I firmly believe that people are able to associate things much more broadly than what the Hollywood tradition of story telling, or the narrative in our Western culture, expect us to do. As a visual artist I have the chance to take part in the idea of how to portray the world. An important task for me is to ask: How do we picture the world around us? And on a bigger scale, how do we picture this planet? This is also what I am trying to do with my most recent works – albeit with small steps.

You surely speak of “Studies on the Ecology of Drama”, a four-screen moving image installation, which premiered at the 67th Berlin International Film Festival this year. Would you talk to us a bit more about this work?

Somebody once said, behind every economy there is an ecology. – We are facing global warming and its consequences, overpopulation and growing economic inequality. We are watching many species disappear forever. We simply need to concentrate on the situation of our planet.

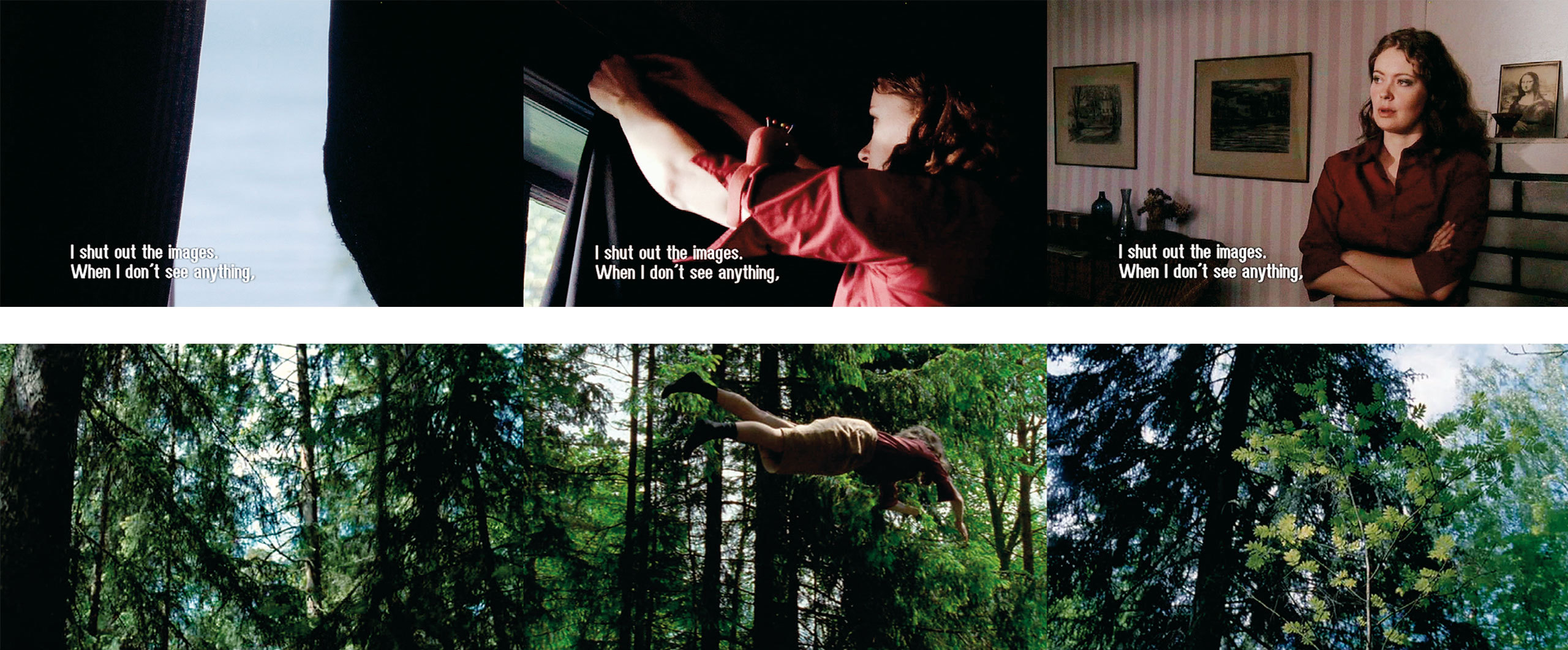

Studies on the Ecology of Drama is a lecture-performance that looks at ecological issues using the methods of presentation as a path to approach other living beings. Performers include a bush, a juniper tree, a common swift, a horse, a brimstone butterfly, and a group of human acrobats in settings such as a field, a forest, the air. The work approaches questions such as: What could an ecological drama in moving image mean and what does it involve? – From there, further questions arise: How to depict living things? How to approach them? How to convey a different way of being, another being's world? – And again: Where does our empathy and ethics lie?

Animals often appear in your works, as is also the case in “Studies on the Ecology of Drama”. What dramaturgic role do they have?

That is the question I’m working with. Studies on the Ecology of Drama approaches that question with different hypotheses and exercises. What role will the other living creatures propose when included in the moving image piece? And what kind of an impact can it have on the ways moving images work and communicate things? It is very interesting and exciting how an altered perception of time can hugely change the idea of a dramatic event.

By doing that I aim to introduce a relevant way of viewing the world – one that is not human-centered, one that shows us as part of the living. I feel it is important that we reconsider our place and role on this planet as human beings – as members of the larger community. A debate about the post-humanist situation and about bio-political issues has started and it is crucial that these topics enter our awareness permanently and have an impact on our actions. As an artist I tackle these issues by using the moving image.

Studies on the Ecology of Drama, 2014, making of, Courtesy Crystal Eye / Malla Hukkanen

Studies on the Ecology of Drama, 2014, making of, Courtesy Crystal Eye / Malla Hukkanen

Shooting a film with animals surely must bring a different dynamic to the production.

It does and it brings a lot of unexpected fun: when we were shooting a scene for The Annunciation in front of the donkey’s box during the first take it started to chew the actress Mary’s dreadlocks and then it neighed as if laughing at us. There was no need for another take! However what probably matters more is the effect on the atmosphere of the film the other beings create – on so many levels. It happens subtly, for example through the pace of movement which again affects the rhythm of editing a scene, or through conscious planning on how to portray living beings, and translating their condition into the language of moving image. For example, how to make a portrait of a spruce tree?

How does one empathize with a creature as the artist and director to recognize its genuine character?

I would not use the word genuine in this context since it is hard to know about that when working with another creature. Also looking for genuity may lead to missing the point. I suppose that mainly one should aim to create a moment of closeness and remain patient and sensitive to note the reactions, or even the absence of a reaction, by the creature. One also needs to be careful with the means of expression of moving image: for example, can we really shoot an image as if perceived from a raven’s perspective?

Multiple-screen installations looking at a story from different vantage points simultaneously have come to characterize your work. How does one actually script a narrative across multiple screens?

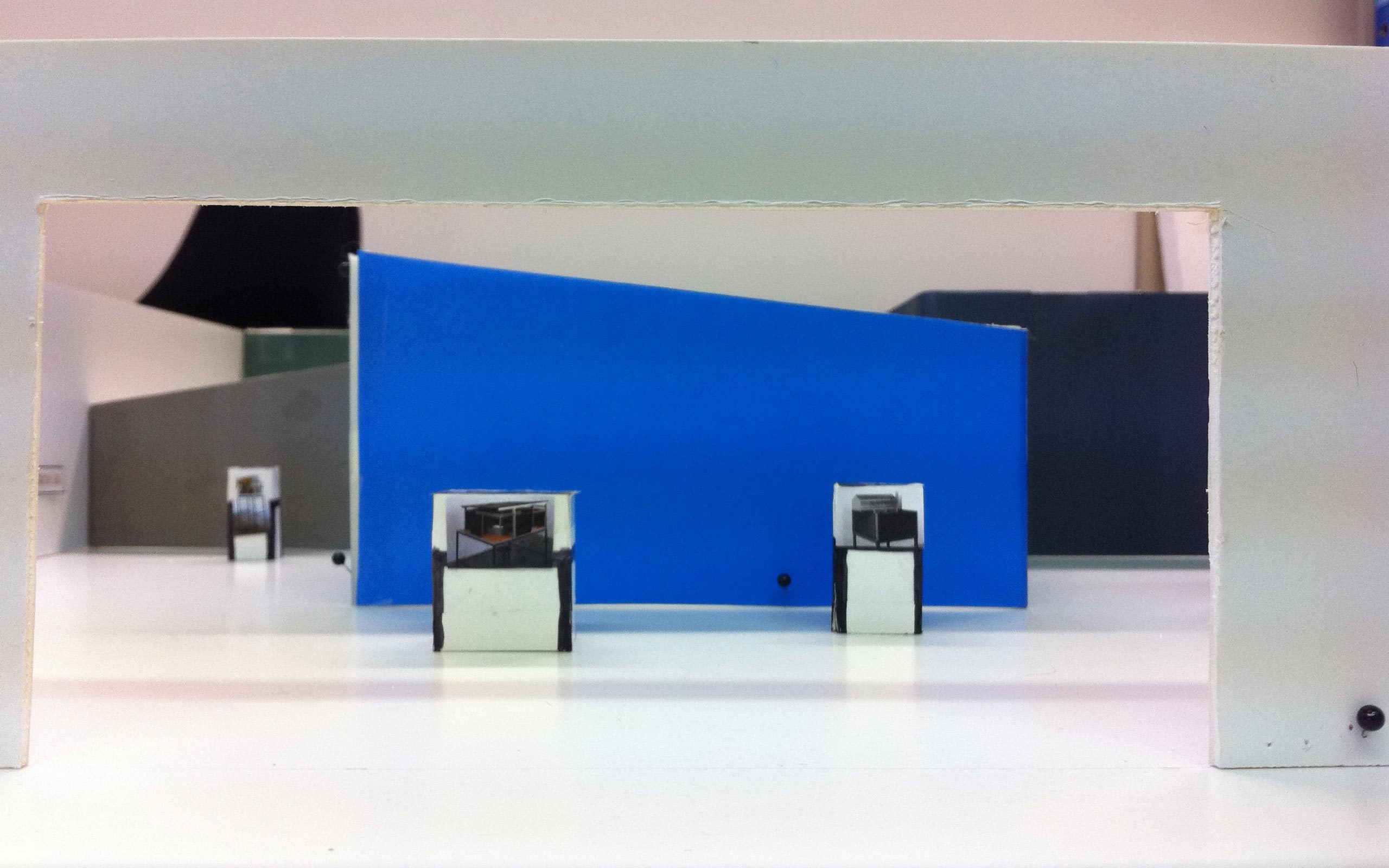

Well, it involves careful visual planning to create a situation where the viewer in the center of the installation space feels like being in the center of the space on screen and among the events.

Before writing, I carry out research, and I create files of sounds, images, colors, characters, pieces of dialog, visuals, sets – plus anything else that feels relevant. In the process of writing I start connecting the pieces and create a structure. Over time, things start coming together.

After scripting I create individual storyboards for each screen. The challenge here is to keep in mind what is going on simultaneously on the respective other screens. In some works, for example in Where is Where, a six-screen installation from 2008, there are scenes where several people are in the same room talking to each other. In the installation this means that actors are talking to each other across the space on different screens. This also involves the direction of the look, meaning that it needs to correspond to the position of the actor on the other screen. Each individual take for every screen has to be choreographed painstakingly to create simultaneous action and continuity among the screens.

What is your dramaturgic intention behind a multiple-screen setting?

To play with the linear perspective and the order it implies – and the viewers’ omnipotence. I’m aiming at creating a cinematic space in which screens interact with each other, making use of the space between the screens, in which the viewers are situated. The viewer enters a state in which she or he is never able to see everything at the same time as things occur in the room. It changes their position as privileged viewers. There are several ways of seeing, not one defined path or angle from which to look at the action. The setting denies a singular perspective of things, or a specific order of how knowledge is acquired. It also emphasizes the fact that we have to make choices about how we want to look at certain things.

Horizontal, 2011, film still, Courtesy Kiasma 2013 / Pirje Mykkänen

Horizontal, 2011, screen capture, Courtesy Crystal Eye / Eija-Liisa Ahtila

In “Horizontal” you created a film portrait of a spruce tree, in six different parts. What led you to the idea and what message were you trying to convey?

The work originated in the shooting of The Annunciation, from 2010. In its production we needed to shoot first landscapes and then trees. When we confronted the task of shooting a tall tree, we were faced with many restrictions – first with the camera, and then with the idea of a picture of a tree. With the film camera and its aspect ratio one can only capture a part of a tree. When backing off, it becomes no longer a portrait of a single spruce, but the picture of a landscape. Using a wide-angle lens produces a distortion effect, which no longer results in an image of the spruce, but in an account of the mechanism of optics.

In 2011, I made the drawing series entitled Anthropomorphic Exercises on Film based on this observation and the limitations the camera mechanism poses for visual recording of our surroundings. Then I thought I might as well take the challenge seriously and make a moving image piece of the attempt to make a portrait of a tree. It is a long story, but to make it short: We shot a 30 meter tall spruce in six parts and presented it in a human space, horizontally, since otherwise it would not have fit inside. That’s how the name Horizontal originated. The more we got immersed in this task, working with technical equipment, that has been made as an extension to human perception, the more we ended up seeing ourselves and the mechanisms of both the machine and the idea.

Unlike your current approach, in which you try to avoid a human-centered approach, humans were very much the center of attention in your earlier works.

That’s true. I created works, which I at some point called short ”human dramas” – something I later regretted. (laughs). I suppose The House from 2002 is the best known work of that time. It is a three-channel video installation, which tells the story of a woman who begins to imagine that she is hearing voices in head. Her awareness of her environment begins to disintegrate, eventually creating a complete rupture of spatial and temporal boundaries. The story is fictional, but it is based on interviews and discussions with women who had experienced psychosis.

The House, 2002, three-screen screen captures, Courtesy Crystal Eye / Eija-Liisa Ahtila

You maintain two different work spaces, both on the outskirts of Helsinki. Which aspects of your artistic work happen where?

In my small studio, where we are right now, I do most of my writing. The space at Lämmittäjänkatu is larger. This is where I do the scale models for exhibitions and all kinds of other models, and where I also do the drawings for the production. I have a large wall with a varnished chalkboard there, onto which I can write the structure of the script. Lämmittäjänkatu is also where I hold meetings with members of my team and with external visitors such as people from museums and institutions. And there is a third place that is very important to me, which is the forest. The forest is the place where I do most of the thinking for my works.

For Studies of the Ecology of Drama you worked with Finnish actor Kati Outinen, one of Aki Kaurismäki’s preferred actresses for his idiosyncratic films, which often deal with the struggle for making a living among Helsinki’s working class. Kaurismäki is a fellow countryman of yours. Do the two of you have things to talk about?

I am a great admirer of Kaurismäki’s films, and how he has been able to create his own “genre” in a way – his economical way of storytelling, his brilliant visual style, and the very romantic atmosphere he creates in his films, which then manage to speak beyond that. Unfortunately I have never met him.

Ecologies of Drama will open at Salon Dahlmann in Berlin in September 2017. Can you give us an outlook to the show?

At Salon Dahlmann, there will be three works exhibited: a three-monitor piece called Me/We, Okay, Gray which consists of very short black and white narratives which I originally made to be shown on TV among advertising and at the same time as an installation in a gallery or museum space. That is one of my oldest works, dating from 1993 – one which then became part of the emerging scene of moving image art during the 1990s. It has been shown once before at Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin in 2000 – a long time ago. It fits nicely in the space and I thought it would be good to present one of the earlier pieces as well.

In the two adjacent rooms one can encounter the spruce. Horizontal will be spread across the east walls of both rooms. This is the first time the work will be shown in Berlin. The third work in the exhibition will be Studies on the Ecology of Drama, unfortunately not as the four-screen version, but only a one-screen film version of it.

You can look at an impressive track record of artistic creation. Your video works have been shown in many of the world’s most recognized museum spaces, including Tate Modern, MoMA, the Guggenheim, and Centre Pompidou. Is there anything new you would like to try out?

Oh there are many things! I would like to have a show in LA, where I lived during the 1990s, to make a feature film maybe and to make a series of small sculptures. And I would love to explore how my multiple-screen thinking and dramaturgy would play out in the context of virtual reality.

Courtesy Eija-Liisa Ahtila/Crystal Eye

Courtesy Eija-Liisa Ahtila/Crystal Eye

Interview: Florian Langhammer

Photos: Florian Langhammer

Links:

Eija-Liisa Ahtila – Crystal Eye Studios

Marian Goodman Gallery, New York/Paris/London