Elfie Semotan looks back on six decades of artistic creation and has long been regarded as an icon of art, advertising, and fashion photography. Her career ranges from striking portraits and shots from the studios of various artists to her landscape photographs and still lifes. We visited Elfie in her studio to learn more about her fascinating career, which began in 1970s Vienna.

Elfie, after attending the Hetzendorf fashion school in Vienna, you went to Paris as a model. How did that come about?

That sounds as though it was a goal of mine. But it wasn’t like that at all. After fashion school, I realized that there were no structures in Vienna for doing fashion in any form. There were only five haute couture salons and maybe one or two prét-à-porter companies, which was quite new at the time. I spent nine months with the fashion designer Gertrud Höchsmann, an avant-gardist of Viennese haute couture. I am still grateful to her for those nine months; I learned things from her that were not taught in fashion school. In school we had nude studies and color theory and, of course, fashion design, which, however, was taught practically without conversation or further introduction. In pattern drawing, which I always thought was really good, we probably made the easiest patterns in the world. But for fashion, working with material, how to make something out of what fabric, is also incredibly important. This aspect was not really addressed in fashion school. After all, the people teaching had never been in Paris or anywhere else for any length of time.

It was actually a courageous step for that time to go to Paris as a young girl without knowing what to expect there.

In Vienna there were no photographers, no magazines, nothing at all. And so I decided: Fine, I’ll go to Paris. Of course, I didn’t know what was going on there. But certainly much more than here, I thought to myself. Which was true. Only I had no money at all and it was absolutely imperative for me to find work immediately. So I called all the haute couture houses. And at Lanvin they told me: Come by, let’s have a look!

It was not your goal to work as a model?

No, not at all, I didn’t love it. In the end, I stayed a model longer than I ever intended. You couldn’t just become a designer after arriving in Paris from Austria, I would have had to study again in Paris to do that. That wasn’t my plan, I just used this time to learn: the language, and to see everything around, everything that somehow has to do with fashion. How it works with photography, what you need for it, how you feel about it. For me, that was a very important experience for later.

When was that moment when you knew: I want to change sides, I want to stand behind the camera?

I knew that from the beginning. I knew right away that I didn’t love being in front of the camera. But it took me a while to start photographing. Photography was not present at all in my childhood. I grew up in Upper Austria, and my father didn’t even own a camera to take family photos, for example. Only my step-grandfather had a film camera for cine film. He always filmed everyone, but we were never allowed to see the result. At that time, I only ever made my drawings, which I started doing at a very early age and won prizes at school. But photography and all the equipment that would have been necessary was very far away.

I imagine that when you returned to Vienna from Paris in 1970, it must have been quite a culture shock.

I would probably never have come back if it hadn’t been for John Cook, who I was with at the time, and who wanted to go to Vienna. He couldn’t make the films he was planning in Paris, simply because he had no connections. But he knew that I knew some people in Vienna. Moreover, at that time the French introduced new laws for models. Until then, it was not allowed in France for women to earn money with their bodies. Models were not classified as a professional group and were not covered by social insurance. This was something none of us knew at the time. And suddenly the government decided: Now everyone will be covered by social security and will have to pay arrears, going back seven years. As a result, all models who could left Paris in a hurry. And I came with John to Vienna, where we separated relatively quickly.

Were you already working as a photographer at that time?

That was when I had just started. Of course, I was incredibly sorry to leave Paris, because I knew so many people. But then I just continued here in Vienna.

Wasn’t it incredibly difficult to start a career as a photographer in the early 1970s in Vienna, of all places?

Not at all, it was the moment when everything was beginning. It was a very exciting time in photography and advertising. Vienna was still not a city for fashion photography, by any means, that only developed slowly. There were also no magazines yet. The Wiener was just getting started, which was great. And there was advertising, which was very ambitious, for which we all enthusiastically developed some kind of stories and implemented them with incredible effort.

When you returned to Vienna, you met the artist Kurt Kocherscheidt and had two sons with him. After your husband’s early death, you raised them alone. How were you able to reconcile career and family?

That was always complicated. I have been asked this question more than once and I have always answered: It’s no problem if you can afford to get help. Then it’s possible. In the beginning, we tried to take care of the children without help. Kurt and I came to the studio later and so on. It worked for a while, but not in the long run. Furthermore, I think it is important that not only those women who have a job and earn enough money are emancipated and can go to work: particularly those women who have little money should be able to consider things other than daily survival like getting up, making breakfast, cooking, doing the laundry, and taking care of the child. Women should have a professional perspective just like men.

Later you were married to the artist Martin Kippenberger, who unfortunately also died much too early. What is your attitude towards art – apart from photography? Are there any artists you particularly appreciate?

I think there are artists who are appreciated more than others. I was able to establish my preference for the artistic milieu at the age of fifteen or sixteen. It was clear to me early on that I would rather not live in the petty, middle or upper middle-class milieu, but that only the artistic one would give me enough freedom. That’s how it turned out. I wouldn’t have fit in anywhere else.

You mentioned that you loved to draw when you were a young girl?

I have more or less given up on that. Photography is so close to reality, so perfect...

Are you striving for perfection?

You could call it perfection in the sense that the photograph meets my imagination pretty much perfectly.

But perfection in the sense of everything being perfect is not my goal. On the contrary, I think if you get too precise and too exact, you often lose a certain mood – a moment that is beautiful.

Photo: Courtesy the artist, Vivien Solari (“Life moves fast” inspired by Jeff Wall), New York, 1999, Elfie Semotan, Courtesy: Studio Semotan

Over the course of your career, there has been a rapid technological evolution in photography: from black-and-white photography to color photography to digital possibilities. What effect has this had on your work?

Color photography came quite organically for me; I always liked colors. There was Kodak film, Ilford film, and all these different kinds of film. And there were also very garish types of color. You could pick and choose whatever you liked. Ektachrome 2 films provided the most beautiful colors. But it was terribly expensive to work with Ektachrome professionally. You had to have so much light because of the low ASA, however, the colors were great and the grain very, very fine. It was a luxury to do that.

The analog photograph in its materiality makes a different demand than digital photography, which already allows the adjustment of the shooting settings in the process of creation.

You had to know exactly what you wanted to do. If I wanted to stage something, I not only had to plan where I wanted to shoot – which is always very important – but also what I needed for it, how the light should be, and so on and so forth. It was equally important to be aware that the concept I had in mind may or may not work. It may be that the whole situation doesn’t work out the way I envision it. It may be that everything else throws a wrench in my plans. Just now I had my work Life moves fast in hand, which I shot for the i-D. What am I going to do with the title Life moves fast, I asked myself. And then I decided to have a girl squat on the sidewalk – without moving – surrounded by things that move very fast. Once we had a nylon bag like that floating around. Or let a toy racing car drive into the photograph, which then was of course blurred. A dog we threw, a fox terrier – all kinds of things. It started off very well. The girl was insanely beautiful, one of the most beautiful girls I’ve ever worked with, and she was super. I really like Jeff Wall’s photo work Milk very much, which shows a man sitting on a sidewalk angrily dispersing milk from a brown-bagged container, i.e., he is not ‘pouring’ milk. Among other things, I also had the model pouring out milk and, of course, had to pull the remote shutter release trigger at precisely the right time because there was nothing to help me yet. Furthermore, I didn’t have a flash, but HMI headlights, which I particularly loved. They are these big spotlights that were also used in Hollywood productions. They produce exactly the same light as sunlight. You can actually construct any face with that light. We know that, we know the shadows, the little ones under the nose and the dark under the eyes. Unfortunately, it started to pour while we were taking pictures. Fortunately, one of the two assistants was brave, the second was afraid that we would suffer an electric shock. It was pouring, the model was sitting under a huge umbrella and we were throwing things at her. It was really adventurous, but we persevered.

Today, we live with a veritable flood of images; anyone can take hundreds of photos a day with their cell phone and distribute them to a huge audience via social media.

I think it’s just too much. Anyone can see the pictures and anyone can create them, it’s a very simple thing. What’s more, with the cell phone you have an instrument in your hand that allows you to correct your inability immediately at the touch of a button. And you can keep trying around until it just happens to work, randomly. Few people use their cell phones to take specific photos.

Instagram photos have their own aesthetic, which in turn influences fashion or advertising photography.

I think that’s good and bad. You can always find a good photo in this flood of photos. However, to do this, you certainly have to look through at least 1,000 photos. I’m not so interested in that. I’m much more interested when someone takes photos specifically, when someone has his personal ideas and then tries to implement them.

You mentioned earlier how a work by Jeff Wall inspired you. Are there other artists who have inspired you?

Of course, American photographers inspired me at the beginning of my career. Spontaneously I’m reminded of the Swiss-American photographer Robert Frank, Alfred Stieglitz comes to mind, August Sander, so important in terms of portrait photography, Edward Steichen, Dorothea Lange, was another great one… They were my first acquaintances. There was a very strong photographic climate in Czechoslovakia. Miroslav Tichý became famous when was already an old man. He liked to photograph women from a distance, through fences or in the bathroom. Even if the quality was mediocre, but often the photographs were beautiful, mostly fleeting, often a bit blurred – photographs of women in bathing suits, who appeared in the photographs of classic beauty. He was visited by many people, threw the photographs on the ground and trampled on them. People picked them up behind him. Tichý rightly became very famous because he had an incredible look; he extended his lenses with paper making a long lens, just tied it together. He just worked crazily wild, wasn’t concerned about anything. I think it’s wonderful when in our super-precise time, in which everything always has to be ever more beautiful, more expensive, shinier, there was someone who simply took photographs with an optical device that was tied together with string.

Is there a difference between whether a man or a woman is behind the camera? To what extent is the female gaze different?

The female gaze is certainly different. I would like to say from the outset that the female gaze is one that perceives the entire surrounding – the children need something to eat, they are crying, there is work still to be done, and so on. The male gaze is focused. That is already a fundamental difference between female and male. And when I see naked women or men, my primary concern is that the models feel comfortable in their role, that they don’t feel exposed or that they have to pretend. When I photographed underwear, for example, it was very important to me that everyone felt very comfortable. And that everything was very loose. It was also rather comical.

How did you achieve a relaxed atmosphere?

We just fooled around. It was nice with the women, because we were just buddies. The model was wearing the underwear, and I was taking pictures and we communicated, I don’t expect anyone to pretend with me. I never could either. There was always a connection; I always gave directives that were easy to follow. You don’t have to say much, models move anyway and you can catch them and build on that.

What if you photographed male models in their underwear?

That was just very funny. During the Palmers shootings Ms. Ulli, an incredibly energetic and competent woman took care of everything, including the underpants that the men had to put on under their underpants. Which we all had a great laugh about, the men included.

I would like to come back to the subject of digital photography. As you mentioned earlier, in times of digital image processing, photography portrays the human body over-perfectly. How is beauty defined against this background?

I think what’s really exciting about digital photography is that you don’t use it to reproduce reality, but to realize ideas, things, images that you have in your head. I think that’s good, too. If you use photography purely as photography, for example making a portrait, then I would want you to see this woman as she is, because I like her as she is. Every person has a certain beauty, a certain moment. There’s no point at all in touching everything up and making everything “more beautiful”.

An extensive retrospective of your artistic work will soon be on view at Kunst Haus Wien. When you look back on your working life, what was the best time?

The best time is always, and it just goes on, I will not stop photographing.

The exhibition Elfie Semotan. Posture and Pose at Kunst Haus Wien is not designed as a chronological presentation of works. What view of your work does the retrospective offer?

Since this is my first major museum exhibition in Vienna, the Kunst Haus Wien wanted to do a kind of retrospective. So I started thinking about how we could do it together without getting too close to a classical retrospective. I began to line up photographs on the wall in my studio, without regard to date, affiliation to a series, or other classifications. I found that exciting and varied. Bettina Leidl, director of the Kunst Haus Wien, and the curator Verena Kaspar-Eisert were equally enthusiastic about the proposal. Then there were some things that I hadn’t thought of, such as photo wallpapers or vintage prints that form a coherent group. These works are too special to split them up and mix them with other photographs. Some portraits are also hung as a group. The eye is drawn from one situation to the next, to completely different worlds. No spontaneous contextual connections can be made; perhaps that will emerge later.

Elfie Semotan, untitled (inspired by Roy Lichtenstein), New York, 2003, © Elfie Semotan, Courtesy: Studio Semotan and Galerie Gisela Capitain, Köln

Elfie Semotan, untitled, New York, 1998, © Elfie Semotan, Courtesy: Studio Semotan

Elfie Semotan, Martin Kippenberger in Issey Miyake, Vienna 1996, © Elfie Semotan, Courtesy: Studio Semotan

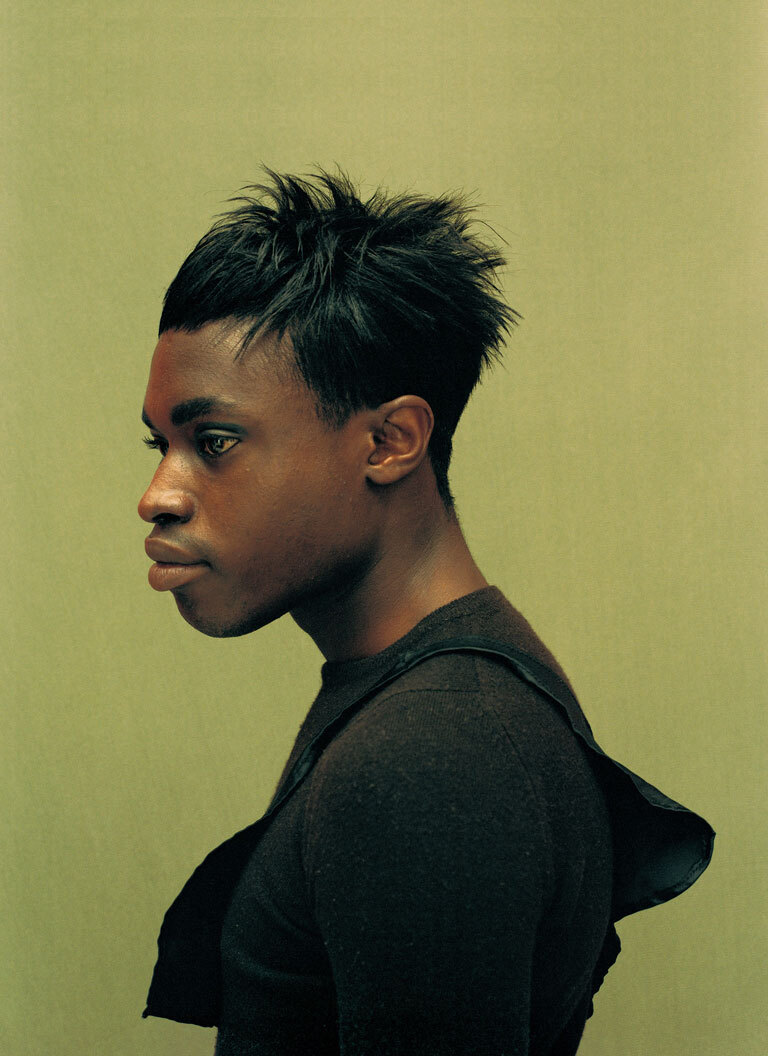

Elfie Semotan, untitled (Hair Story), New York, 1997/2021, © Elfie Semotan, Courtesy: Studio Semotan

Interview: Barbara Libert

Photos: Christoph Liebentritt

Links: