Since the beginning of her career, Eva Schlegel has been interested in the topic of immaterial space. She combines techniques and materials; her works include graphite and lead paintings, photographs, videos, pictorial objects, mirror sculptures and sculptures in augmented reality. In 1995 she represented Austria at the Venice Biennale and in 2011 she was the commissioner of the Austrian Pavilion there. Schlegel taught at the Academy of Fine Arts from 1997 to 2006 and is a recipient of the Austrian Medal of Honor for Science and Art.

Eva, your permanent mirror installations are accompanying the magnificent staircase in the newly renovated Austrian Parliament over a height of 17 meters. Your art could hardly be displayed more prominently – what is it like to receive such a significant commission?

I don’t want to sound jaded, but when the invitation to the Parliament competition came, my first reaction was: “I just don't have the time!” When I entered the building, however, I found that the magnificent staircase and the glass dome room were positively overwhelming. This resulted in the strong desire to work on ideas for the competition. However, the presentation of the designs took place during a heatwave, at noon in an attic, and the attention therefore was rather subdued! (laughs) I could hardly believe I had won the contract.

How did your work with mirrors come about?

It all started in 1997, when I received a commission to create art for a building. The place was an underground car park with very low ceilings, which immediately made me want to create more room down there. I thought about putting up mirrored circles... And finally distributed 400 polycarbonate mirrors all over the ceiling. When people come into the garage, they look up and adjust themselves. After that, I used mirrors more and more.

But for you, mirrors are less a way to reflect oneself than to open up space?

Yes, exactly. When you see mirrors, you ask yourself: Am I there? Do I exist? One wants to assure oneself of one’s existence. The Parliament commission was about space too. You look from one staircase to the other. My sculpture expands this space, even deconstructs it, but it does not reflect the people walking on these stairs. It has a timeless, eternal feel. People may come and go, but the space remains the same.

How does the idea for a work come about?

When I participate in competitions, I follow the guidelines, and then the situation or the building tells me what it needs. You have to listen to it. When the Museum Liaunig commissioned me to create a smoking pavilion, for example, I thought of my usual theme of space. I wanted to slide mirrors walls into each other and build a house out of them. I think the client might have imagined a glass house at first... but he was finally completely convinced by the mirror pavilion.

And what about non-commissioned work?

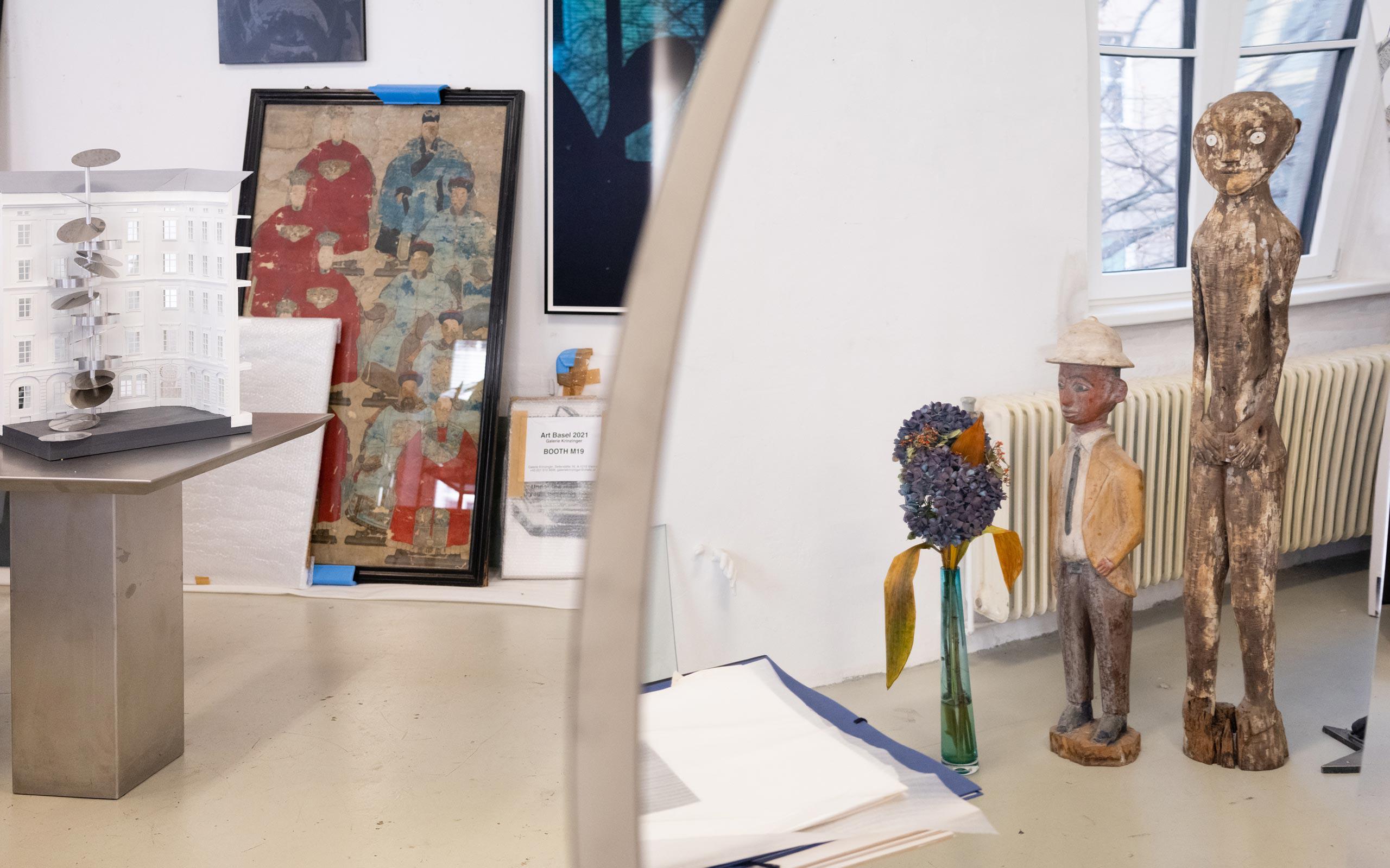

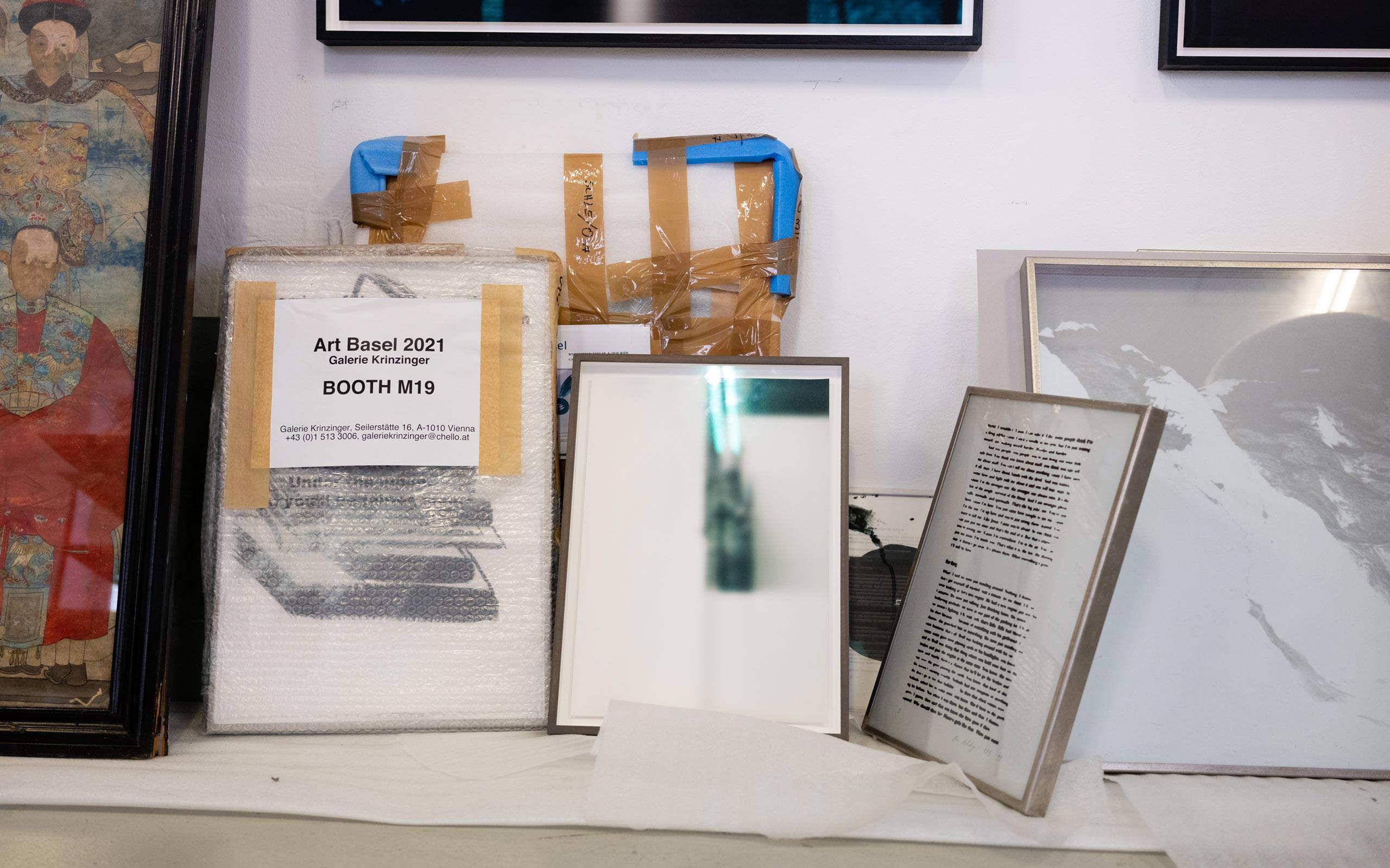

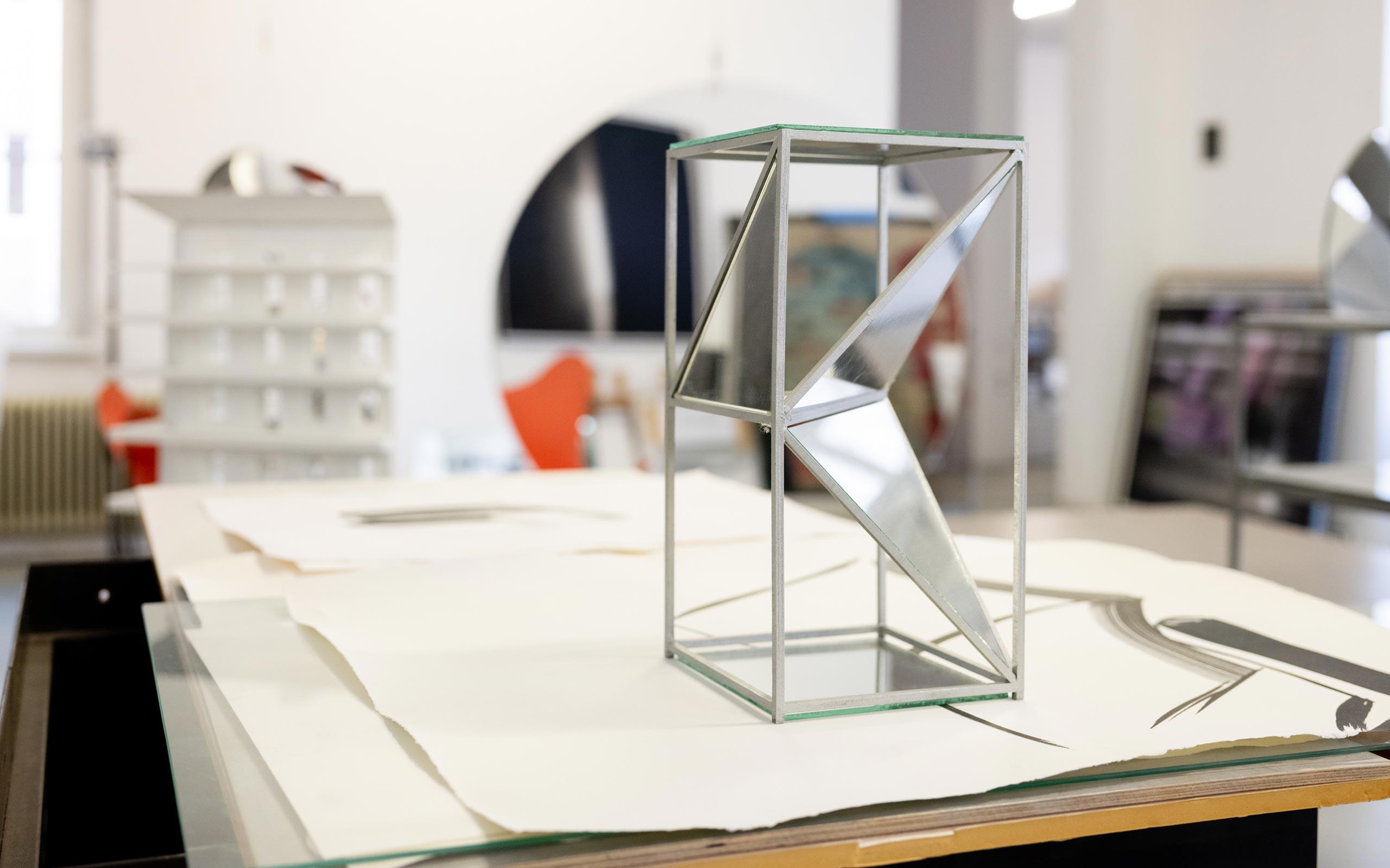

This is different; it’s difficult to say how exactly it works. When I think of my most recently exhibited works, created during the pandemic: I started by building architectural models with a student. I then photographed them, therefore creating pictures that are not based on real templates. I call them “Liminal Spaces”, which is a term from ethnology: When societies fantasize themselves into a frenzy, it is a liminal space, a threshold or in-between space. In the gamer society, on the other hand, liminal spaces are artificially made spaces that are abandoned and scary. My work, I believe, expresses both.

But you did start with sculptural graphite work?

Before graduating, I had experimented a lot with film and photography, for example creating an installation where I filmed a rotating fan with super 8 film, and then projected the film directly onto the moving fan. After my Diploma, however, I wanted to produce art that could be sold. This is how the graphite work came about. For this I used a metal sieve, on which I applied plaster by hand, blackened it, and then overdrew the entire surface with pencil. And because the pencil does not get into the recesses, they remained black.

There again is your theme of space?

Exactly, that is what it was all about. Those were abstract drawings in wet plaster, very sculptural. Later I added lead because it has a similar color to graphite.

After 1992, however, you didn’t do any more work of this kind – why stop when it was so successful?

At that time, I showed large graphite works in a solo exhibition at the Museum für Moderne Kunst, at that time still housed in the Palais Liechtenstein. The most imposing of these was 3.60 meters high and 1.80 meters wide – exactly the measure of the doors in the Herkules hall! And then I thought: “The work is great, but it can only get larger from here on.” I no longer saw any possible development in this medium for me, and at the age of only 32 I didn’t want to do continue doing the same thing forever.

Such a turning away from one's own, already successful art must require a lot of courage…

It was horrible. I took a year off to do research and to develop a new direction. Everything was half-baked, it was a difficult time.

But did you know what your topic should be?

My theme is always space, the immaterial space. Perception and creating something that leads you to question your own perception, this is what interested me the most.

This lead to your group of works in which you present blurred texts…

During this year of crisis, I read the grammatology of Derrida (an approach of the philosopher Jacques Derrida, in which he develops his theory of writing) – although with the help of a dictionary of foreign words! At that time, I created abstract architectural models out of glass, and randomly placed books behind water glasses, and then saw the text blur. I thought: “If I leave out everything that is too beautiful and kitschy, only the text remains.” So I photographed the texts in graduations of blurriness and printed them onto large scale glass plates. I leaned them against the wall, overlapping; and everything was suddenly out of focus. You could see the structure – that those texts were poems or scientific treatises – but you could not read them.

So the question arises whether one recognizes these works as an image or as text…

You automatically identify them as text! It is an ingrained inner knowledge, resulting from our experience. I am interested in the exact degree when readability is no longer given.

Blurring also characterizes your work group of women’s photos. Is it the same principle, do you want to make these women disappear?

No, here I used blurring to take away the women’s individuality, and especially the facial expression as the seat of this individuality. I wanted to point out other characteristics, such as the expression of the body. That is why there is a whole range of works in which women occupy different positions and are therefore perceived differently. There are playful or dominant, flirtatious, or sexy women.

Although he does not see the woman clearly, the viewer associates something with her. Does everyone see the same in your photos?

There is such a thing as a cultural code in the West, and most people living within the same cultural space associate in the same way. Anyone who grew up here, in the west, has a kind of dictionary of recognition at their disposal. As far as body tension is concerned, the perception and association go even further – it unites all people. Body signals are unconsciously understood, even if they come from strangers from foreign cultures. You just “get” things without needing to explain them.

Do these photos represent your view of women within their environment?

I would rather say that they represent a perception of a society. I wanted to point out that women are mainly portrayed in an idealized way. That is why I took the first photos I used from magazines and enlarged them many times over, because these women have something aloof, overwhelming. This also applies figuratively: These images influence our judgment, our thinking, our perception. Later, I photographed women myself in order to get complementary poses – for example, an expression of guilt, or one with no body tension.

Is blurring also a way for you to protect women? So that they are not stared at as if they were an object?

Yes, that is a good point. I want to give women space – and also freedom. I used to smoke a lot, the smoke was like a protective barrier between me and other people. My works with blurred text and the blurred photos of women have a thought, a question in common: Do these images appear or disappear? These works describe a path, a space, an in-between space really.

You have been starting a new body of work in augmented reality since 2021 – how did it come about?

The curator Jürgen Weishäupl approached me about an AR exhibition with Erwin Wurm in Palermo. The plan was to scan sculptures and then, via a QR code, put them outdoors. By downloading the code on your mobile phone, you could view them and photograph them. I was immediately interested in creating sculptures that do not depend on gravity.

How did you realize those?

I have a fantastic team: the architect Valerie Messini first designs the sculptures with me on the computer, and Damjan Minovski, a computer architect, provides the renderings and films. The two – they call themselves 2mvd – are a contemporary package with a great understanding of art. For Palermo, for example, we created an ice ball that rotates on its own axis, a star ball, flying eyeballs... These were my favorite augmented sculptures by the way: they are cute-paranoid!

Isn’t it just a step from augmented reality to NFT’S?

I always wanted to do them, but honestly – it does not feel right to me yet. I’m not interested in GIFs. Until recently, there was some sort of gold rush atmosphere to NFT’s and many went for it. To me, it would be important to develop my own way in order to create meaningful content.

You work successfully in various kinds of media – when did you have the feeling that you had “made it” as an artist?

I come from an economically oriented family, concurrently there was great concern at the beginning that I might not be able to make a living from art. So when I finished my studies, I thought: “If I manage to live on my income by the time I reach 30, then I’ll continue, otherwise I’ll look for another profession.”

And that worked?

Yes! On my 30th birthday, it was clear that it would work out; I had sold works, was represented by a gallery, and had already exhibited in Los Angeles and at the Sydney Biennale. Also, at that age, you are not so demanding regarding your lifestyle. But yes, it was a truly uplifting moment.

During your studies at the Academy of Applied Arts you had some doubts... What was the time there like?

There was actually nobody in the classroom, and our professor Oswald Oberhuber stopped by only once a week. In my perception, the students were arrogant, they all knew what art was. And I didn’t! Out of this dissatisfaction arose the desire to go to New York, to learn something. Those were the years 1982-83, the time of the Neue Wilden artists, the New Wave music, so I wanted to see what was going on in NY.

And – what was going on there?

At that time, interestingly, there was a lot of European art in the galleries and museums in New York. Before that, in the time of American Expressionism, Europe was dominated by the Americans. In the 80s, many Germans were present in New York, which I thought was great. I lived with two friends in a music studio, we helped the musicians with their setups, we lived at night. That was an exciting time because everything was new.

So you did not necessarily go there to make art?

Rather to see art. But what is art? On the floors below and above the music studio there were huge studios, 20 painters were there in the evening in shared studios, working on their art after their bread jobs. At the time, the NY Times wrote that there were 90,000 artists in Manhattan alone. At first, I thought I could stay there, washing dishes during the day and doing my art in the evening... But then I realized that I would not be able to, I just had not enough energy.

Eva Schlegel, extension of public space, 2022, Photo: Iris Ranzinger

Eva Schlegel, parlament vesti, 2023

Who were the artists you discovered, and who inspired you?

Julian Schnabel, Rainer Fetting, the artists at the Mary Boone Gallery. What really hit me was an exhibition of Donald Judd at Leo Castelli. There were cubes whose bottoms were made out of red and green plexiglass. The whole room volume was color! And then the earth space of Walter de Maria! I also loved John Baldessari, these artists touched and fascinated me greatly.

Isn’t it a contradiction that minimalism generates emotions?

Yes, totally. But the minimalist manifestos touched me more than painting. That’s how my enduring love for the concept and for the abstraction of space came about.

You exhibit a lot – do you generally have the feeling that female artists are more present today than in the past?

I am not so sure. I am always upset by themed exhibitions which include very few women. There is always the excuse: “There simply are no women, or can you think of female artists?” That is why I have a list of Austrian and international female artists ready. By the way, I loved the artistic activist group Gorilla Girls, who already put the question to the public in the 1990s: “Does a woman have to be naked to get into a museum?” and who specifically compiled statistics about the proportion of women artists in various museums and group exhibitions.

Does that concern you as an artist? Do you feel like you are being left out?

I am honestly very concerned about the proportion of women in group exhibitions. While the Aperto Biennials in Venice of the last 8 years are positive examples, there are too few women in many group exhibitions still! I personally had many opportunities to show my art, but overall, it could be better. When I was a student, there were few female professors. You had to get used to being alone as a woman, to being disempowered. Yet more women than men study art... I had many female students.

As a professor, how did you work with your class?

Back when I was a student, there was no control, you were given no tasks, and exposed to your past, your future, your present to the maximum. You really had to live through this feeling of being lost. That is what I wanted to pass on as a professor. Of course, we offered one-on-one conversations to help the students when needed. But it was important that they develop something by themselves. Because after graduation, nobody helps you either, it’s just you in your studio!

What advice would you have liked to receive as a student?

That it is important how you talk about your work, how you plan exhibitions, how you present yourself. Because talking generates thinking. When you word something, you have developed and understood it. It is crucial to be able to explain one’s own art and its references.

What is your favorite project?

I really like my more complicated projects! Those that were especially difficult to realize, such as the smoking pavilion, please me most. I’m also looking forward to the installation in Campell Park in front of the Oklahoma Contemporary, which will open on April 26, 2023 and will be on display for a year. And we are working on milling a mirror disc with a diameter of 10 meters into the roof of an old brick factory building in Mühlheim an der Ruhr in Germany; it’s going to be incredibly beautiful, James Bond-like. I really enjoy it when I can think big!

Interview: Alexandra Markl

Photos: Christoph Liebentritt