The minimalist form defines the works of the Altshausen-born object artist Gerold Miller. His wall objects achieve their impact through radical monochrome and geometric abstraction. He uses modern techniques and materials, such as aluminum or stainless steel, to support his works, creating a symbiosis of sculpture and image.

Gerold, you have been working as an artist for many decades. Did you come into contact with art as a child?

Even as a child, I knew that I wanted to be an artist, there was no alternative for me. I grew up in a rural area where there was no real art scene, so I had no concrete idea of what it meant to be an artist. That’s why I had to invent myself.

How did you manage to create this space for self-discovery?

As a teenager, I exhibited and sold paintings at our garden fence, that I had found in the basement of my parents’ house, I replaced the original artists’ signatures with my own signature. This act of signing or subversive appropriation became a pictorial gesture that already pointed to the minimalist-conceptual spirit that still characterizes my art today.

And did you already apply this kind of appropriation to spaces back then?

The area where I grew up was strongly influenced by the Baroque period. I also developed my understanding of art from this: The baroque concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk, the merging of architecture, sculpture and painting, the combination of real space and spatial illusion. This became the basis of my artistic development and still occupies me today. I also try to concentrate on things, to focus on the essentials and to formulate statements clearly. My works should be unambiguous and direct.

What role does your youth in southern Germany and your studies at the Stuttgart Art Academy play in your work?

Everyone who undertook studies at the academy in Stuttgart in the 1980s had to complete a foundation year in which one was meant to learn basic skills such as drawing, painting, etc. We had to work figuratively, which I categorically rejected. After this first year, I had two options: to continue with a sculpture class with an abstract approach, led by a stone sculptor who was inspired by the Bauhaus, or to attend Brodwolf’s class and his strictly humanistic approach, which interested me greatly and still plays a certain role in my work today. So, I opted for Professor Brodwolf. Back then, the academy had a very good steel workshop where we could work, which many sculptors did at the time. Metal has remained my most important material to this day.

What was the first exhibition that influenced your work?

It wasn’t an exhibition, but rather a work of art, namely the large-format studio view by Gustave Courbet from 1855, which hangs in the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. The picture contains the entire cosmos of the artist. His friends from artistic circles, writers, critics, the model in front of a canvas, all gathered in the intimacy of his studio. The real life of the painter versus his inner world – these are elements that every artist is constantly confronted with.

Your works are at the same time abstract and minimalist. What else characterizes your art?

My works are anchored in reality. The emphasized materiality of certain groups of works creates situations that I would describe as physical and psychological confrontation. For me, the investigation of the possibilities and conditions of imagery in the border area of sculpture, plastic object, delimited wall surface and sculpturally and pictorially defined space as an image carrier is central.

To which genre would you classify your art?

As my works are neither pictures, nor reliefs, sculptures, or architecture, they do not belong to any of the usual genres and leave conventional definitions behind. For me, the idea of the image does not end in the tangibility of a minimalist “what you see is what you get” but goes far beyond that into a conceptual realm that can no longer be physically grasped and is only conceivable.

Your works are often based on investigations into pictoriality on the borderline between minimal and conceptual – what unites these two forms of expression?

For me, the relationship between conceivability and visibility, geometric unambiguity and visual ambiguity as well as the opening of the pictorial space into reality are central concepts. With these themes, I see myself more in the tradition of the Italian avant-garde artists of the 1950s and 60s.

What role do space and time play in your work and how do you approach these concepts?

The setting of art as place and time plays an important role throughout my work. I deal strongly with artistic parameters that were also characteristic of the 1960s, such as process, i.e., time, action, and trace, which disrupted the static nature of art at that time and thus tied it even more to the factor of time. In 1996, as an artistic action, I had a dog mark the four corners of the exhibition space, which for me is a spatial description, a sculpture.

Which work shows this most clearly?

Another example is my relatively small group of works I Love Kreuzberg from 2006: For me, Kreuzberg is comparable to the uncharismatic directness of raw aluminum. That’s why I dragged unprocessed aluminum forms through the district on foot and by car, so that Kreuzberg left its traces on the work. This deliberate abandonment and leaving the result to the street chance is the basis of something like my own form of a spatial-temporal inventory and location determination.

It is similar with your work media – what makes the combination of sculpture and painting so special for you?

The combination frees the two genres from formal and content-related restrictions, making them the ideal “carriers” of my artistic ideas. The American art of the 1960s and the Neo-Geometric Conceptualism of the 1980s are very important to me in this context, as both art movements have strongly influenced my artistic work. In the 1960s, the radically reduced, industrial anti-aesthetics of the Minimalists stood in extreme contrast to the bold, figurative aesthetics of Pop Art. Nevertheless, they strove for similar content and socio-critical goals, which were best expressed through the new formal parameters common to both art movements, such as grids, seriality, color intensity, etc.

What follows from this?

The product of Minimal and Pop, the Neo-Geo of the 1980s used a similar strategy and turned geometric abstraction as a universal language into an aesthetic survival model with which its representatives wanted to ensure artistic agency within an extremely complex and constantly changing reality of life.

What does a typical day in the studio look like for you?

For me, my studios are places where I can develop my artistic ideas in peace and quiet, usually while listening to music. This is the setting in which the creative process takes place. Some days are more creative when there are just a few people, others are more productive when there are lots of people. For me, the studios are test laboratories where I can plan at large tables and experiment with new ideas. I sketch my designs with collage-like cardboard models because I want to see straight away whether they work in the room and whether the proportions are right. This direct and fast way of working suits my approach. What I still like after a thorough examination is then built to scale into an architectural model and realized

Is precise planning necessary for this type of artistic work?

Yes, because in terms of the work in my studio this means that I always have to think about the next step: What is in production, what is going into which exhibition? My studio manager and assistants take care of the rest of the organization, such as communication with the galleries, the staff such as the transporters, the technicians and the photographer. It all has to be well coordinated.

Do you work in several studios?

Yes, I have two studios in Berlin: a smaller one in the city, for the office, archive, and planning, and a large studio space in the south of Berlin. I also have another one in Italy.

What happens in the different studios and to what extent does Italy inspire you?

We work in three studios. The city atelier in Berlin’s Schöneberg district is mainly a place for planning and administration and contains my archive. In the south of Berlin, we have a large studio hall for the presentation of the works and storage. The studio in Italy consists of several rooms in a historic ensemble of buildings dating from 1792. The rooms there, function more in the sense of a studiolo, where I can apply my experimental way of working. Ideas are first tried out there and then groups of works are developed further.

What role does the connection between people and construction play in your work?

As a young person, you decide early on whether you want to depict or construct. I opted for the latter. For me, it’s always about the relationship of scale between man and artwork, his contemplation, his counterpart. What you see is not absolute but depends on random temporal and spatial factors of perception. This becomes particularly clear in the amplifiers and large-format sets, in which the theme of simultaneity also plays a certain role: On the reflective surfaces of these works, people can experience the world as both simulated and real at the same time.

In your famous key works, the black set, you combine sculptural and pictorial experiences. How does that work together for you?

I try to involve the viewer in my investigations into pictoriality through the process of perception. I no longer make “the painting” or “the sculpture” in the traditional sense, but rather a sculptural space and projection surface for images, in which the viewer has to be proactive in finding the actual image. Especially when standing in front of large-format sets, it becomes clear how strongly they work with surface and space, light and dark. Their deep black, reflective surfaces absorb the gaze and allow illusionistic depths to emerge from the surface. With these works, I have succeeded in combining the idea of image and space in a way that is ideal for me.

What current projects are you working on at the moment?

I’m currently planning new groups of works for the next exhibitions. At the same time, I am preparing the conversion of my city studio in Berlin and the concept for a sculpture park in Italy.

What future exhibitions can we expect?

There will be several museum projects this year. In spring, an exhibition in Madrid at the Casado Santapau gallery. Later this year I am planning exhibitions in New Zealand and Australia. My 2nd solo exhibition at Galerie Wentrup in Berlin will follow in the fall. I am also working on an exciting museum project in Berlin, which will run parallel to the exhibition at Wentrup this fall.

The Venice Art Biennale will be taking place soon. Will there be anything on show from you?

My Berlin gallery Wentrup is opening a second gallery in Venice for the Biennale. There will be several works on display, including a stone sculpture made of Italian marble in the outdoor area.

Your art is generally very free of concrete references. Do you still see a form of commission?

Reality and art share the same present, which is why I cannot escape a certain social responsibility, I am aware of that, and I accept the responsibility. Every artistic work is a statement and therefore political in its consequences. Through my artistic work, I want to create an intellectual space that encourages reflection without committing myself to themes and statements.

instant vision 39, 2008, from the Nationalgalerie Berlin Collection, Credits: Jens Ziehe

set 296, 2015, Work from the Stadler Collection

Verstärker 1, 2016, from the Siegfried and Jutta Weishaupt collection, Credits: Jan Windszus

Interview: Kevin Hanschke

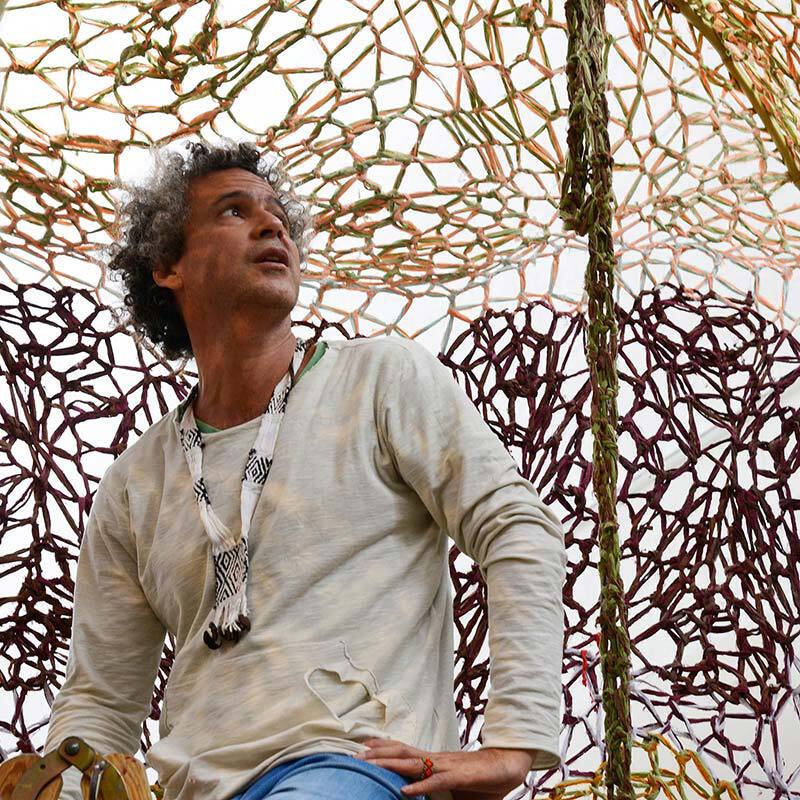

Photos: Patrick Desbrosses