US-born digital performance artist Gretchen Andrew quit her job at Google to go on and ‘hack the art world’ instead. She has used her technical expertise to make images of her playful paintings and collages appear as the top search results for unrelated terms, including ‘the next American president’ and ‘Frieze Los Angeles’.

Gretchen, how would you describe your work and what you do to someone who knows nothing about it?

I want to rule the art world with a bejewelled open poem. I imagine it as one of those big toy circular lollipops – something absurdly oversized. The elements of my practice: painting, drawing, coding and search engine manipulation are really all ways of transforming power. There’s the power of the image, the power of the internet, and the power of certain people or systems in the art world. I put my paintings into these systems with a lot of intention so that on the other end, I am transformed, my life is transformed and so is the system itself. If I were to explain my work to someone who doesn’t know it, then I’d say I hack systems of power with art code and glitter. I make paintings so powerful they have manipulated election results, major technology companies, and the art world. By injecting something new, in this case, my work, into these systems I begin to bend them. Google’s search results bend to my will, Facebook’s tracking software bends to my will and as someone in the art world, I am a force bending part of the world into the way I would like it to be.

How did you get from working at Google to wanting to be an artist?

I was only at Google for 18 months, but I think I was lucky to get out of what was supposedly the absolute best job in the world when I did. At the time, I just knew that I was very unhappy. I didn’t see people like me succeeding and I didn’t feel like I could be myself.

Why was that?

A lot of it had to do with my gender and not having the tools to exist in a space that was, and I think still is, a group of men who consider themselves the underdogs. They got picked on in high school for being nerds. They don’t see themselves and especially didn’t then in the 2010s, as the most powerful people in the world – which they are. There were things like not being able to figure out what to wear. I was intentionally dressing down trying to make clear I was just another Google engineer but then I’d be told I needed to dress more presentably. And I was like, ‘I thought this was Google? – why is no one telling the guy in the kilt who hasn’t showered for four weeks that he needs to change?’ I realized I was playing somebody else’s game and I was losing.

So you wanted to try winning as an artist instead?

I wanted to become an artist because I saw artists as people who are rewarded for being themselves. The art world looked fancy from the outside and it intrigued me. In a word, you make yourself, you define what it means to win. Every world has its complexities and its darknesses but I wanted to become an artist because I wanted to be celebrated for being myself – that’s my guiding force in everything I do.

What led you London?

During the pandemic, I had a studio in Los Angeles, and I realized what I really wanted to do was to move back to London. I’d lived there in my early 20s and have a good community of peers there. It was a personal choice to move back but it had very good professional reach too.

And how did you end up at artist Billy Childish’s studio?

There was an element of naivety there. I felt the sort of purchase you have as a foreigner. I was open because I was admitting that I didn’t know much. It’s interesting because I felt able to do it in London when I would have been terrified to do it in New York. London has a very real art scene that I had no idea would become such an important part of my life. Having declared I was going to be an artist and that I was going to use the internet to make it happen, I had been trying to spend time in any artist’s studio that I could. I was already in the UK when I saw Billy’s work. And it’s the sort of work that made me fall in love with art and wanting to be an artist. I love that it has its origins in things like Van Gogh and Edvard Munch but exists in contemporary spaces.

How does your digital performance work relate to your paintings?

Learning to make art from Billy, I learnt that art could do something we can’t talk about, something nonverbal. It can do something that isn’t related to language or conceptual art. This is still at the heart of my work, the on canvas painted and drawn images. But I wrap my work in conceptual, performative and digital elements that I can talk about. The context that surrounds it and how I present it and doing so protects what I find very secret and almost sacred in art.

What do you want people to see, feel or experience when they look at your work?

Reclaiming technology as a positive space is part of my mission. Behind the glitter is this idea that we as artists are world makers. I think that world exists not only on canvas but in our homes and in our own minds as well as on the internet. I would like to inspire people to be more themselves. When people see my vision boards (inspirational collages made up of images of things you want in your life) they look like they’ve been done by a child, one who’s very skilled at drawing but who like, went to a craft store. I’m able to bend the global internet – that’s a terrifying thing. A lot of artists direct attention to the darkness of technology but I want to use it as a creative medium instead. That way it becomes fun and playful while still addressing serious topics like fake news and digital manipulation. I deal with people’s expectations of gender and technology and power and I’m not someone who wants to fight against systems from the outside. I take the rules, whatever these rules are and however terrible these rules are and try to make them do unexpected things.

Why did you choose to make London’s iconic Barbican Centre your home?

For years I had this idea of myself living in the Barbican in my retirement – I even made a vision board. I carried this notebook with me which contained photos of the Barbican and how I’d like to decorate it. I saw myself being this old eccentric lady wearing a robe and slippers with monographed initials on them, maybe curlers in my hair. I’d wear this outfit to the orchestra and to the theatre and to the art museum because it would all be my house. And I just thought, why do I have to wait to be that person? I want to start this now.

And why did you want your studio there?

I wanted to create my studio as part of the narrative of my work and have it located in a place where I could get a more diverse group of visitors. In my work in general I believe in meeting people where they are and taking them on a journey from there and the Barbican felt right for that. I consider the whole thing very performative – I call my studio the Barbican Beach Club, a joke on this whole Warholian idea of the factory. I wanted to create and to play with this idea that we all just lie around and drink champagne here [laughs] – which is equally as false as the idea that that’s how it was at Warhol’s factory. Part of my practice is using my work and everything that surrounds it to become the person I want to be.

And who is that person?

Aspirationally relaxed? [laughs] Surrounded in luxury. I’ve got these artworks hanging in the studio right now that are of a vanity and a bedroom. These vision boards are my source material for creating this very real studio. So, I take symbols and metaphors of luxury and transform them into actual luxury, which is what the Barbican is.

How does your work fit into our time?

Since I began as an artist there have been huge trends into the world of AI and everything, with NFTs being in the popular conversation but my practice hasn’t changed at all – it hasn’t been impacted on a seasonal basis. I feel like the conversation is evolving around it. While there’s a lot of doom-mongering around AI and tech I think our best hope is in repositioning our relationship to the technology and thinking about it as like a fun and playful creative place where its limitations and failures have creative benefit. There are themes within my work I want to be eternal such as systems of power and institutional critique. I don’t think technology automatically grants you access to power, but I believe we can bring more of ourselves into the world with things like AI. I came up with these systems of technical manipulation because I love literature and linguistics and bringing these things together is how my artwork is created. We need people who exist in different orbs having parts of their brain talk to each other and I think those interactions can help change the conversation entirely.

How do you think you have evolved since you first started out as an artist?

I’ve gone from being somebody who was making stuff that nobody cared about to having opportunities to grow – whether it’s working with a museum director in Santa Monica or having a newspaper column, these are all these little blocks of power I’m able to use. The best way to describe my transformation is that I used to be someone who felt at the mercy of these power systems and now I’m someone who increasingly has them at my mercy.

Can you give some examples?

I’ve hacked Google with my Vision Boards and I’ve hacked Facebook with my Affirmation Ads and I’ve also hacked the art world system. The art world likes on canvas, unique artworks that hang easily in the home. I’ve reverse-engineered the systems of value. I’m a digital performance artist who has a painting-based market. I have found many ways to put myself into my work while doing this. I think there will be people in the art world who are afraid of me because I can control narratives online. But I think the best way to address problems of power is to become a powerful person and not to sacrifice who you are but to think of it as a way to make changes.

Contemporary Art Auction Record, Origami money, "at least you are cool on the internet" iron on patch, and charcoal on canvas, 152.5 X 122 cm, with thanks to ELEKTROHALLE RHOMBERG Gallery, Salzburg

Contemporary Art Auction Record, Playing cards, pink skull and crossbones fabric, princess shower curtain, and charcoal on canvas, 152.5 x 152.5 cm, with thanks to ELEKTROHALLE RHOMBERG Gallery, Salzburg

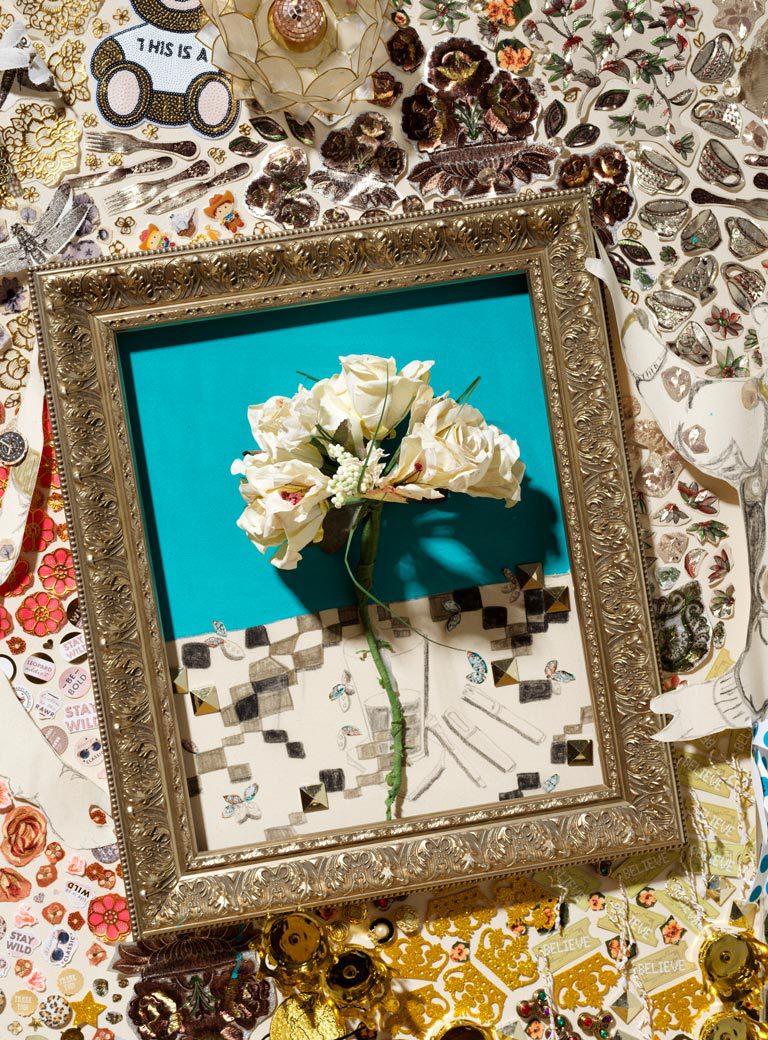

Contemporary Art Auction Record, Ornate frame, sequin bears, "believe" gift tags, and charcoal on canvas, 152.5 x 122 cm, with thanks to ELEKTROHALLE RHOMBERG Gallery, Salzburg,

Now that you’ve hacked the art world where do your next challenges lie?

I’m not done with the art world but it’s now rare for someone not to give me the time of day and that feels huge. At the same time, the art world systems are not the only systems I take on, I’m taking on Big Tech, political systems, geographic boundaries and election results. I don’t think I’m going to run out of power structures any time soon.

Do you think the rise of generative AI tools like ChatGPT will change your work?

I think it’s very cool that these tools have been given to everyone but the fundamental conversation around the technology, which I’ve been part of for the last decade, hasn’t really changed. By injecting my work into Google and getting the top search results I’m actually changing Google’s input and changing the AI system – I think that conversation will have legs for a while given everything that’s going on.

And how does your work fit into that?

I want to keep pushing people to question the underlying dependencies of AI, whether it’s language or input. I don’t believe we should be trying to get rid of bias in AI, or that we should be trying to sanitize these datasets, but that we should be putting more bias and perspective into AI. Monopoly power has not served us well in technology so I think there should be more AIs and mini-AIs. In art there’s an understanding things are created from a perspective and I want more bias in AI because that’s how we are going to get something better. I’m optimistic about my position as an artist because anything I love and do well is not threatened by technological advancement. Understanding that lets me thrive.

Interview: Frederica Miller

Photos: Liz Seabrook