Haleh Redjaian’s varied work ranges from drawings and textiles to wall mounted and spatial installations. Her abstract works and complex systems of order result from lines and forms with which she continuously develops new structures, geometric forms, and compositions. Haleh’s endless serial repetitions of extremely delicate individual elements, which are evidently hand made, suggest a patient humility in terms of creating and producing, which in turn indicates an equally intense concentration of perception.

Haleh, your drawings, wall pieces, and installations are subject to enormous precision. Can you provide insight into your way of working?

Drawing is the most important medium for me. It is the most direct way to visualize an idea without relinquishing too much information. On paper I can begin to develop an idea into different directions. Both patterns and systems of order can be strongly shaped in the process and always stand in direct relationship to objects, architectural fragments, and the nature of my immediate surroundings.

Do influences from your homeland Iran serve as inspiration?

My works are also influenced by traditional systems of order and patterns as can be found in the teachings of Sufi art and architecture which has for centuries contained a tradition of ornamentation placing great symbolic value in geometry and mathematics. However, I use this knowledge in a very abstract way because both my patterns and systems are strongly formable. This way, a new visual space evolves which is not fixed, but has the capacity to be manifested in the most varied ways. By integrating random irregularities in the pattern and order systems of my work, a recognizable image of latent deterioration is gradually created and is observable over time. Such infractions that constantly shift our perception invoke order and chaos, repetition and fragmentation.

As raw material for your work you like to use certain carpets which you commission from a small family firm in Iran. What exactly interests you there?

I treat the hand woven carpets from Sirjan (a town in South Iran) like a blank surface, like paper or canvas. In most cases, the carpets have no pattern and are woven from pure natural wool. Each of these weavings has its own form and grade of strength. The result therefore often deviates even when measurements are given. Small mistakes and inconsistencies occur like an imperfect grid. The interesting thing is that I have to calibrate the work process and the grid completely for each new piece. Not before I hold the carpet in my hands can I begin with a new design.

As with a hand woven carpet detailed repetitive work goes into the work, which requires a lot of dedication and patience. Is your work also about a certain deference with regard to the craft?

When I begin to work this aspect is not in the foreground. It evolves more from the idea and the work process, how elaborate and detailed the drawings or textile work becomes.

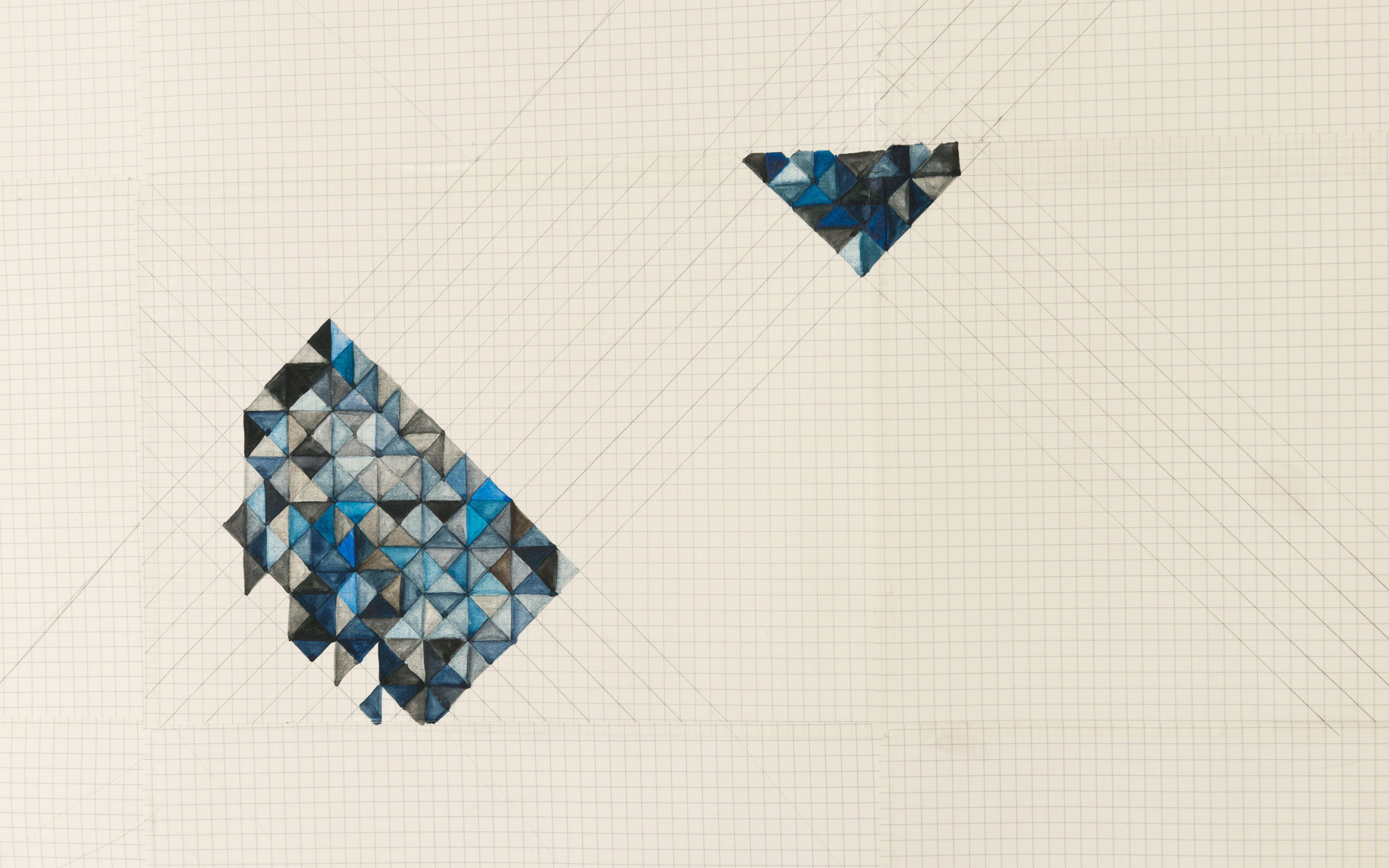

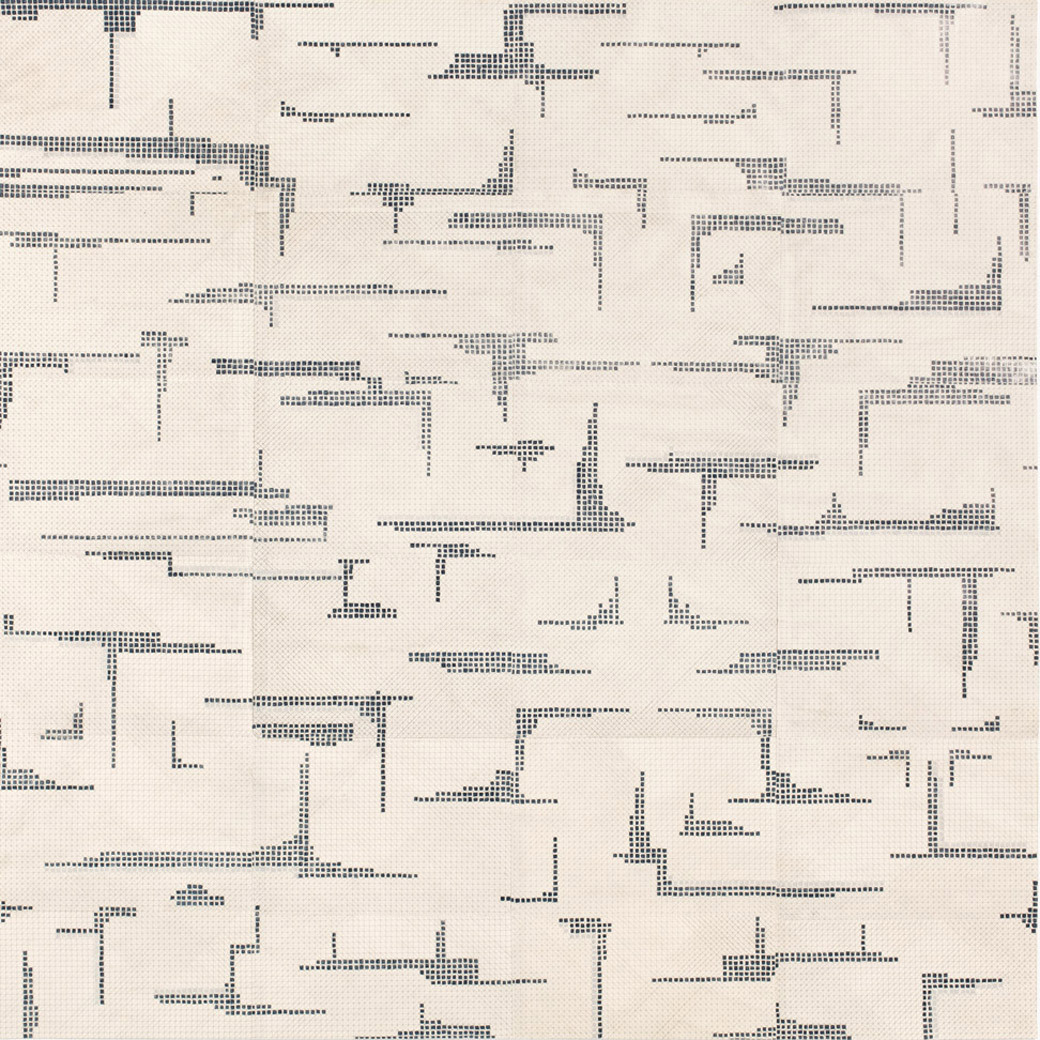

Untitled (C_V), 2014; Photo: Eberle & Eisfeld;

Courtesy of Arratia Beer Gallery, Berlin and the artist

Courtesy of Arratia Beer Gallery, Berlin and the artist

A portrait on Deutschlandradio Kultur emphasized the poetry in your work. Does this reference to poetry mean anything to you?

Actually, I never thought of myself as particularly poetical. However, having said that, at home I was certainly surrounded by the works of Iranian poets and by a poetical language and although I was not aware of it for a long time, poetry has often been a source of inspiration to me.

In your installations you always include the space in which you work.

Precisely, my installations evolve almost always from space-specific designs. In this case, the space is the protagonist receiving a new role through the installation. Space and architecture are activated through an intervention, which in turn defines a new surface. The design can be minimal. Since certain light conditions and atmosphere always pre-exist in a space, that place influences the installation in its own particular way. Conversely, through the installation in-between spaces and light are newly perceived. In the case of wall pieces or installations I have to be flexible in regard to the existing surfaces. Moreover, I usually need the help of assistants. The work therefore also carries the handwriting of another person, requiring flexibility from me.

After a certain time, many space-specific works find their way to other places causing this original reference to space to be lost. Is this alright with you?

The impermanence of these pieces is connected to the concept of subjectivity and flexibility. I am fascinated by both the intense energy I put into a wall piece and at its inherent impermanence. What remains in the end are only traces, memories, and perhaps good documentation. The only time in which the space is perceived together with the work is actually during the duration of the exhibition.

As you just mentioned, many of your works have to do with architecture, because they result from an interplay with space. For Gallery Isabelle van den Eynden in Dubai you put the Azadi Tower, an architectural icon in Teheran, in the center of your work. Why?

The Azadi Tower (Freedom Tower) is the building that has engraved itself deepest into my childhood memories of our travels to Iran. It was always the first monument one saw on the way from Teheran airport to my grandma’s house. The building is constructed of white marble, and even when it was in the process of design in the late 1960s, computers were used to calculate the dimensions of each stone. The inner sides are covered with elaborate traditional ornaments.

The building itself is a combination of Islamic architecture and Sassanid style art. I was especially interested in the curves and rotations of the Azadi Tower, and how my interpretation of it has translated into my work. I am interested in the impact architecture has on us, how certain monuments and buildings anchor us, make us feel at home, connect us in a specific way to a place and form us. A building like this is filled with the emotions and experiences of people, who feel connected to it.

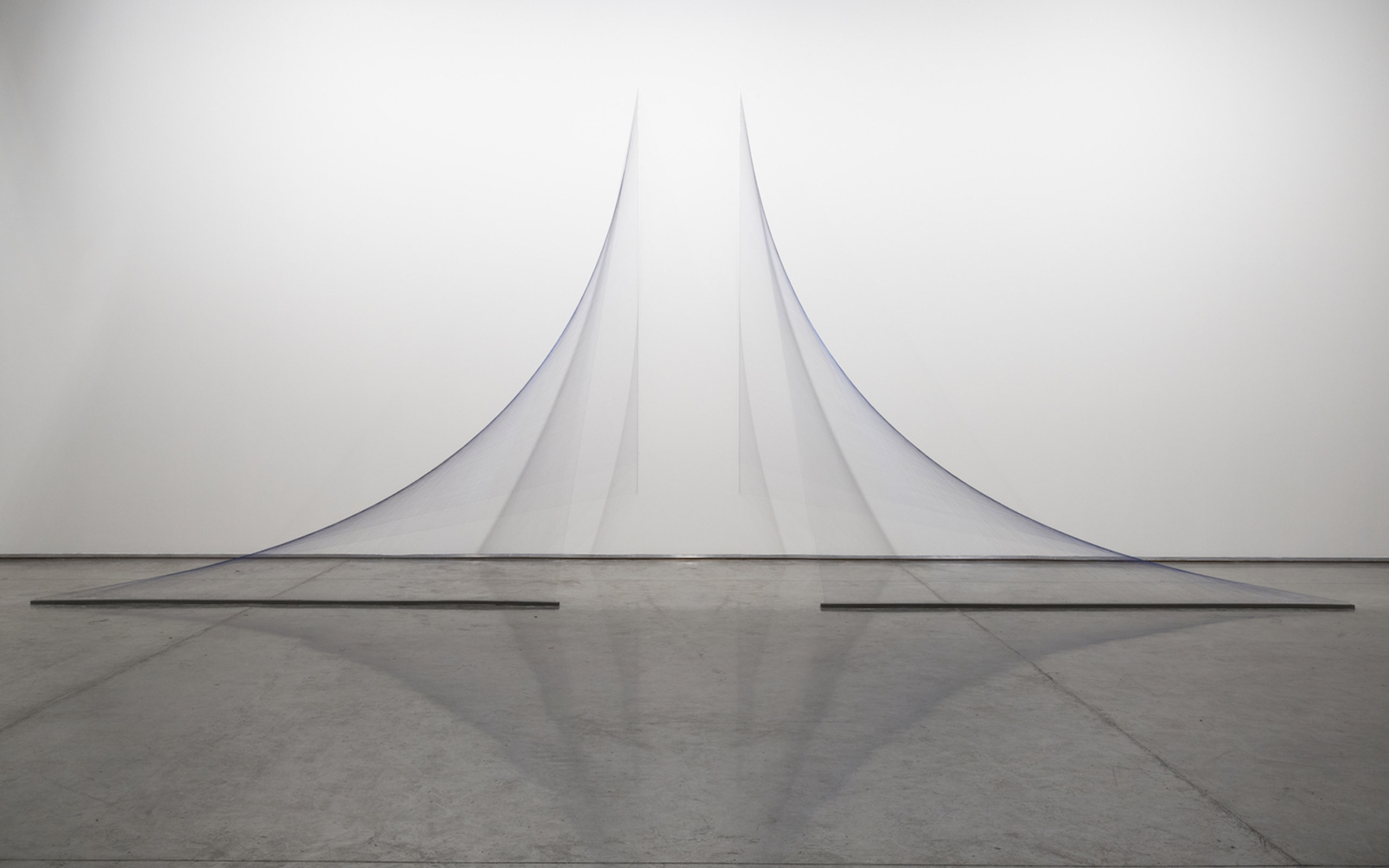

In between Spaces, 2015; Courtesy of Isabelle van den Eynde Gallery, Dubai

In between Spaces, 2015; Courtesy of Isabelle van den Eynde Gallery, Dubai

You are a German-Iranian artist, born in Frankfurt, but seem to have lively childhood memories of Iran. What connects you with your second homeland today?

Firstly, the part of my family that still lives in Iran and memories of my childhood. Even if I was not born and reared in Iran, I spent a lot of time there up until the age of nine. The memory of the landscape, the view of the mountains surrounding Teheran, the buildings, and increasingly the language, but most of all the humor… we laughed so much!

Does the political opening of Iran influence your work, has the attention you receive changed?

At the moment, it is not the specifically political opening that has an impact but rather the general focus on the Middle East.

Do you think that you could have developed as an artist in Iran?

That’s hard to say. It would probably have been different, but it’s possible.

Are you familiar with the Iranian art scene?

Lately, I’ve read more and more about it and through social networks one learns about it. More by chance I‘ve gotten to know some Iranian artists in the last two years. When I was in Dubai I met some Iranian artists who live there. Some cooperate with galleries there. It seemed to me as if a sort of meeting place for the art scene had established itself there. In Berlin, too, I am in contact with some Iranian artists.

How did you come to make art?

Initially I studied art history. During my studies the idea of studying art evolved and I began to apply to art academies abroad. At the time, I felt that I had to gain distance from my surroundings in order to find out for myself whether it was the right step. So I landed in Antwerp. It soon turned out to have been the right step and the time spent there was fabulous!

Has your family supported your decision to study art?

Well, my family was rather astonished and would have preferred that I had chosen something “more secure.” But they accepted my decision and always stood behind me. Of course it was tight at times and difficult when I had to work three jobs on the side as many artists do. However, I also met incredible people in those jobs who now are among my good friends.

How did you find your style, and the development towards what you do today?

At the Antwerp Art Academy we had a very classical education. We drew a lot, every day for hours, which was perfect for someone like me who had to learn the skill. After my studies, my work became more reduced and abstract, it was a slow process and one that must certainly be allowed to take place.

Are there people who you admire or who inspire you?

There are many people who inspire me in my life and who help me a lot, I am very lucky.

Are there any exciting plans for you this year?

At the moment I am working on the next solo exhibitions for 2018 at Arratia Beer in Berlin and Isabelle van den Eynde in Dubai.

Between you and me, 2014; Photo: Eberle & Eisfeld;

Courtesy of the artist and Arratia Beer, Berlin

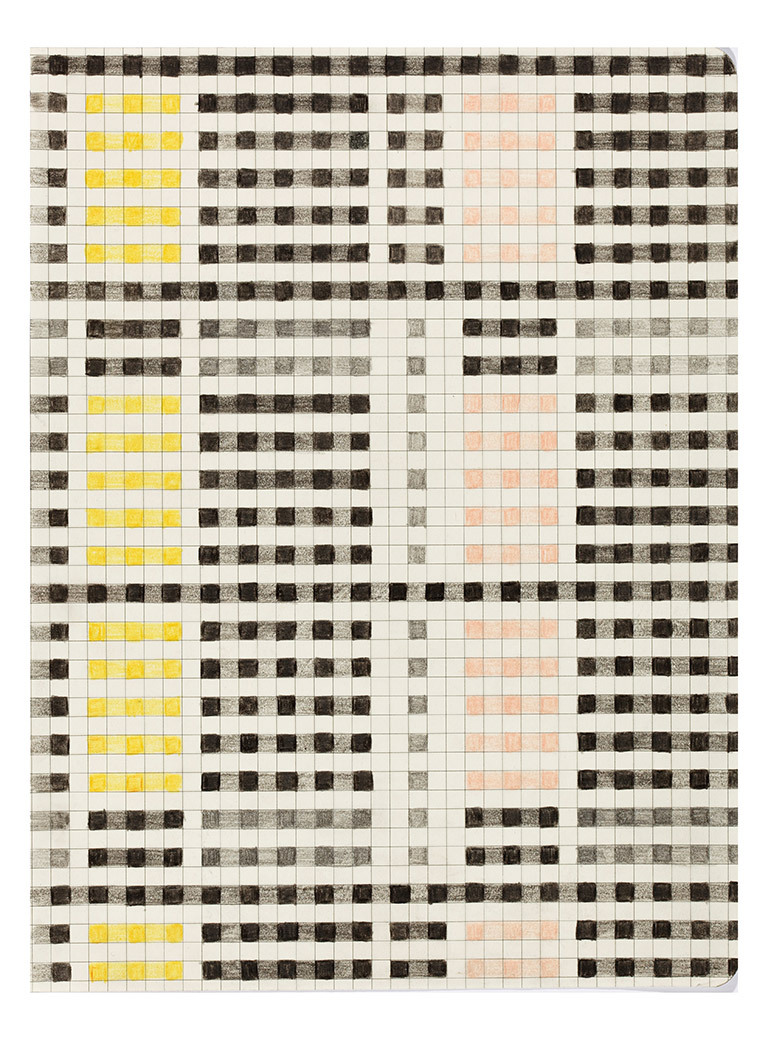

My Morning Sun..., 2016; Photo: Eberle & Eisfeld;

Courtesy of Arratia Beer Gallery, Berlin and the artist

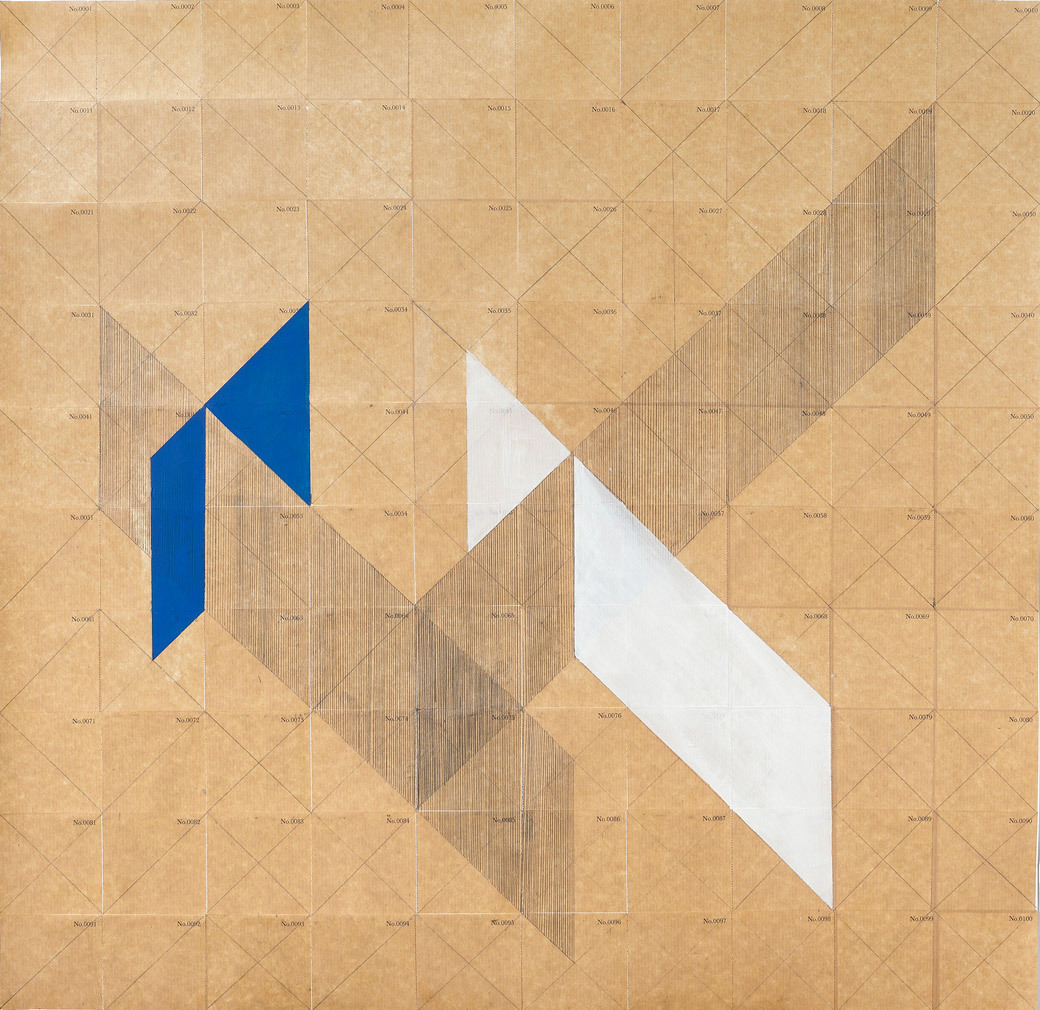

Numbers in Space I, 2017; Photo: Eberle & Eisfeld; Courtesy of Arratia Beer Gallery, Berlin and the artist

The Trick is to Keep Breathing, 2014; Photo: Eberle & Eisfeld; Courtesy of Arratia Beer Gallery, Berlin and the artist

Interview: Julia Rosenbaum

Photos: Michael Danner

Links:

Haleh Redjaian website Arratia Beer, Berlin Isabelle van den Eynde Gallery, Dubai