In her art, Japanese artist Haruko Maeda combines Shintō traditions from her home country with Western concepts. Thus, she approaches the theme of transience through religious iconography and symbols from different cultures and refers to works of the Renaissance and Baroque in terms of content and form. In doing so, she addresses universal questions about life and death, skillfully playing with subtle humor in her confrontations.

Haruko, you initially studied fine arts in your hometown Tokyo. How did that come about?

I can’t answer this in one word ... I grew up in Tokyo and where I lived until I was 20. I was always surrounded by art, so it came natural to me to engage myself in art. My parents, too, were involved in art, so as a child I started painting on paper with high-quality brushes and colors at a very early age. But as such, I didn’t think too much about it and just decided to go to art university in Tokyo, because I wasn’t so good in other subjects, especially mathematics ... I was very good at sports, but that wasn’t so fascinating to me, so I just went in the direction of art.

Ultimately, you completed your studies in Linz …

I didn’t move directly from Tokyo to Linz, but went to Germany first. The art studies in Tokyo were very bad and they just didn’t suit me. The admission was extremely hard, I felt broken and sick afterwards. In addition, the studies were very academic and the tuition fees were high. It seems that in Japan, it is mainly those with money who are studying art. Only a few students can really afford to take on this debt because it is almost impossible to repay it. I knew that in Europe there are hardly any tuition fees and I was curious about the European art scene. Initially I was in Germany for a year and a half, first in Munich, then in Berlin, because I knew more about Germany. But then a friend told me about the art university in Linz, where she had studied herself, and that it had a very family-like atmosphere there, and I thought: OK, I don’t care where I study. I passed the entrance exam in Linz and immediately moved from Berlin to Linz.

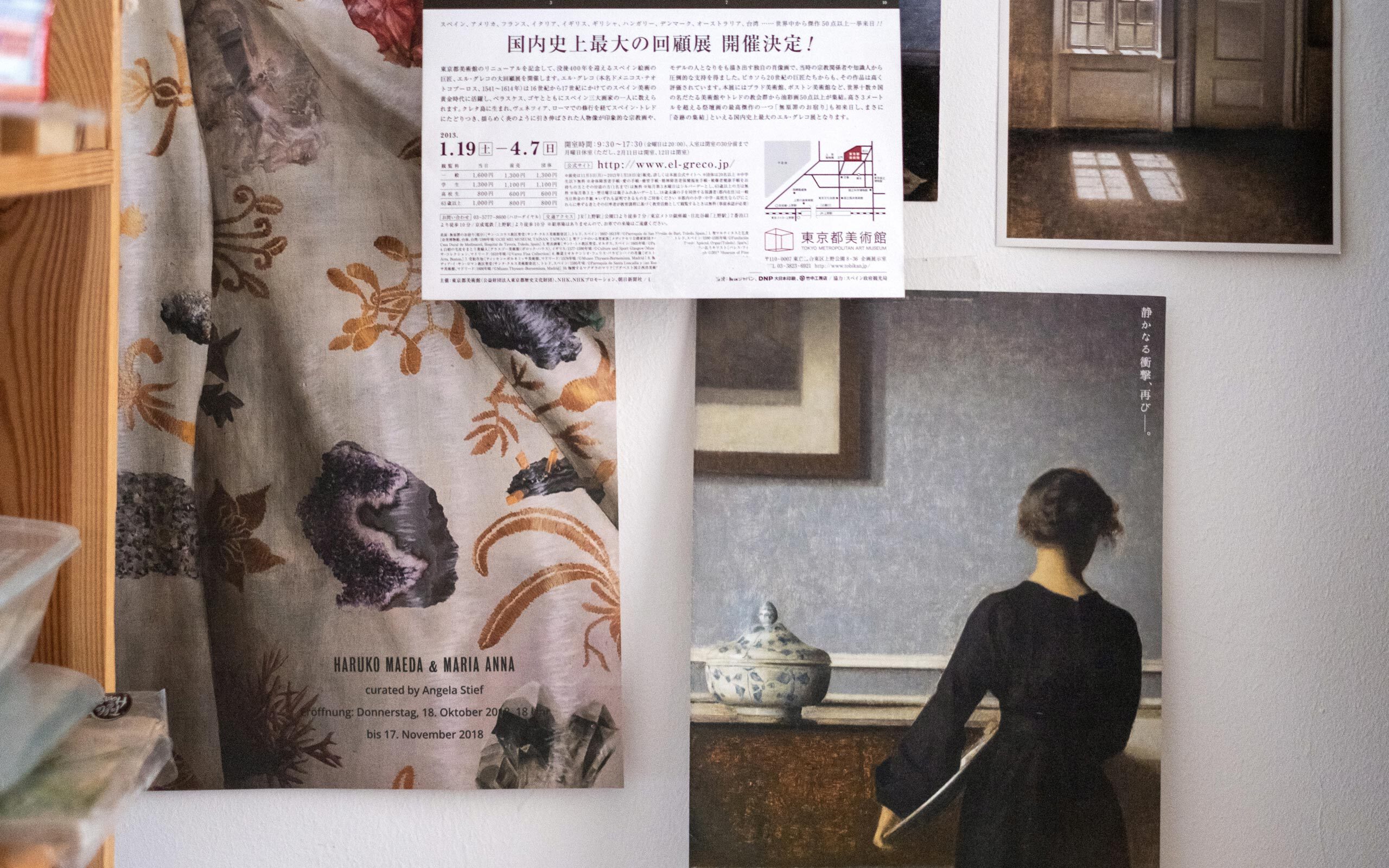

Haruko Maeda, The Great Bouquet 4, 180 x 130cm, oil on canvas, 2021

What is the most important thing about creating art for you?

Although it is fun to make art, every now and then I have a phase when I no longer want to paint a picture, it seems too exhausting. But I keep painting because essentially I enjoy producing art, making good art. I have a passion to improve my art, although I am very critical of my work, and losing would not be good. I want to produce the best work and I think it is good for me, to always give one hundred percent. I don’t always have to be satisfied with my work, but that is how I motivate myself, because I want to paint increasingly better pictures.

Impermanence, life and death are the main themes in your work. Have you dealt with these themes from the beginning?

I started dealing with these themes during my studies during a course in Linz. We were planning an exhibition and one of the lecturers inspired me to research relics and transform them into art. I did a lot of research and the subject of relics in Catholic-European culture began to fascinate me. However, the theme of death was somehow there from the beginning. As a child, I lived in a large social housing project and experienced that many people committed suicide, including one of my schoolmates, although he was only ten years old. The experience made me think about death at an early age. In my art I wanted to combine death and life, but to not only show the dark side.

In your work you combine eastern and western approaches and play with religious iconography and symbols.

In Japan, there coexist two religions – Buddhism and Shintoism – although they are not easily distinguished from each other. Today, many young Japanese are no longer religious, but they do participate in various religious activities. They like to celebrate the festivals of the various religions, including birth anniversaries in the Shinto shrine, or getting married in Christian churches, and wanting to be cremated in a Buddhist temple after death. I like this mixture in Japan. I’m not religious myself, but Shintoism is about life, it’s about the NOW. On New Year’s Day you visit the shrine or temple and pray for the coming year – life is always in the foreground. Thinking about death and its meaning in both a religious and cultural sense as done in Europe was very new to me. In my work I try to combine both.

During the pandemic, your focus has been more on the self, although the issues haven’t changed.

Before the pandemic, I didn’t focus so much on the self. Only at the very beginning, when I arrived in Europe all by myself, without family and friends, I painted a lot of self-portraits. And remembering that I was so afraid to live here alone, led to that. I experienced great fear, but at the same time hope and passion. I remembered that at the beginning of the pandemic, because for a few weeks I was alone in Vienna; it felt almost as when I first came to Europe. And I asked myself, what do I do now, what is it I want to do with art? And I knew, I had to do something during this time, that it was a great chance to use this time, and so I painted myself.

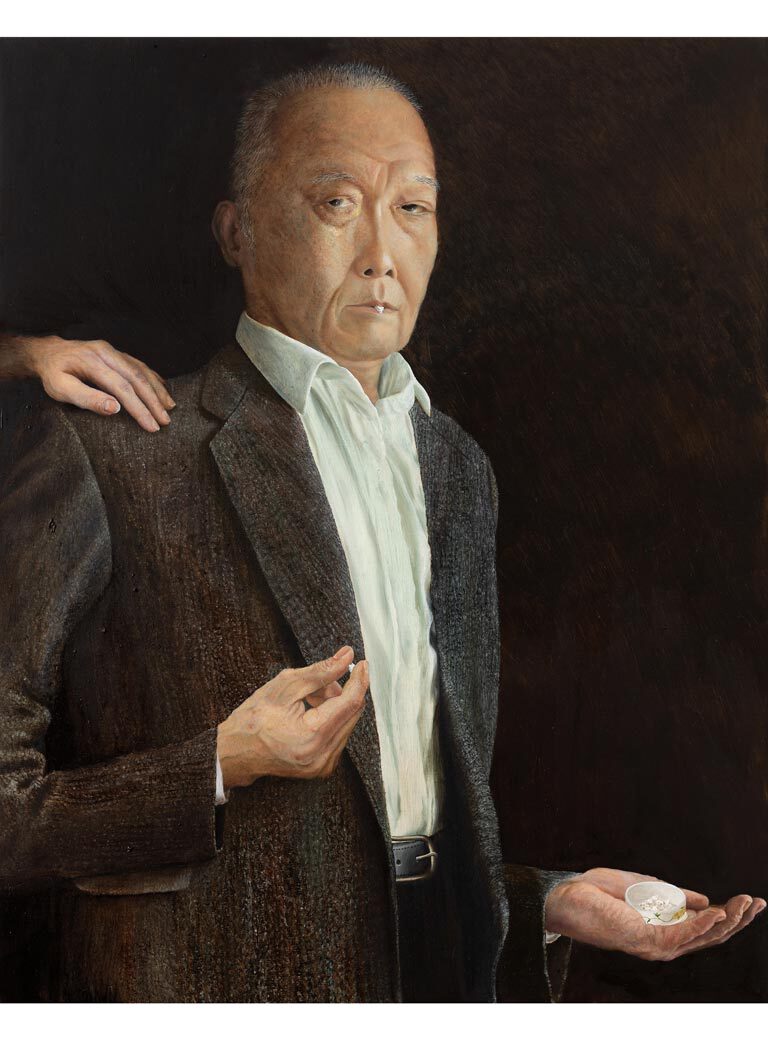

Is this how the portrait of your family A Family Portrait – My Father, My Grandma in his Mouth and I (2021), which hangs on the wall here in the studio, evolved?

Yes, exactly. You can see my father, my grandmother, and myself in it. My grandmother died three years ago and I couldn’t go to the funeral. But I do have pieces of her bones and ashes here in my apartment that my father gave me because he didn’t have money for a funeral. There is this tradition in Japan that you swallow a part of the loved ones who have passed away. My father did this, I did it too, and this portrait addresses that.

Haruko Maeda, A Family Portrait, 100 x 70 cm, Oil on canvas, 2020

How can we imagine your working process?

Most of the time, a painting in process is hanging here at the wall, and I ponder how to continue it. Sometimes I have an assistant who helps me. But in general, no one sees the process of how I create my work which is very intimate.

And what is it like when your works leave the studio? Are there reactions that you would like to see or is there something that you want your works to achieve?

I like it when viewers stand in front of my works, take a close look, discuss, and think. That is my goal. Often, many works are hanging in a group exhibition, and it is sad when visitors just walk past my works. It feels great when they stop and stay in front of my paintings for more than five minutes, because there are so many details to discover in my works.

What artistic role models do you have?

There are many... I love Jan van Eyck, also Hans Holbein – they are my inspiration when I am painting pictures. But at the same time, I like contemporary artists, like David Hockney and the Japanese artist Makoto Aida. I feel a certain kinship with these artists, they don’t stick to one style of art, use various techniques, so that they can represent topics in many different ways. And that is exactly how I want to be. The themes may perhaps remain the same, but they’ll be diverse in their representation, this also applies to my sculptures and objects.

Simply speaking: How would you describe your art?

There is always something humorous. I want my work to remain interesting and fun, even when I paint skulls, so that people linger longer in front of my paintings or objects.

Are there any prejudices or misunderstandings about your work?

There are. There’s a series with skulls such as Maria Anna of Austria (2018) with these baroque garments and one day I got all these friend requests from people from the Goth scene. And it was then, okay, I painted skulls, but their meaning is different. Yes, skulls are catchy, but they are also very meaningful, and I wanted to show life with my paintings.

And how does your art fit into the present?

At first glance, my work may seem old-masterly, yet thematically it is contemporary. Life simultaneously means death as shown in my painting The Great Bouquet (2018) which reveals a lot about me and my life in Austria through picture elements like cat food or my hair on the floor… It is, in fact, also a kind of self-portrait.

You live and work as an artist in Vienna, but you teach in Linz. Does working with students inspire you?

Yes, it does. Each year I have students who are motivated and who have surprising ideas that I don’t expect. And that’s what I learn from. The students are like sponges, they soak up my advice and develop their work and are extremely flexible. And that’s what I want to retain for myself ... to use creativity and something new for myself. Of course, there are also students who say, “I’m already quite happy with my work, I don’t have any artists I like right now, I like my work” and there is no development, and I think, why are you studying right now?

Can you imagine what you would do if art didn’t exist in your life?

Yes, I’ve been thinking a lot about offering homemade food at a market. There’s one right near me and I’ve been wanting to offer my kimchi there. I love to cook and somehow it’s not so unrealistic ... I don’t want to have a shop, but I want to be able to sell something spontaneously.

Do you think your work has changed much over time?

I don’t really think about it that much. I paint what I want to paint, and after I’ve painted, I realize that my painting automatically deals with the theme of life and death. I don’t think so much, you know, it always has to remain with these themes. However, when I pursue something with interest and paint, it comes naturally, I’m always trying to paint differently... In the meantime I’ve also made sculptures and I also carve. I have this collaboration with my cat, I had a mouse that she caught stuffed and then I put a coat on it, which I made from my cat’s hair. Initially I only painted pictures, but since I have my cat I have been producing sculptures, including gold-plated cat excrement, excrements, in itself a kind of relic, which I will also exhibit in Krems.

Your exhibition Der Wein ist schon reif in der Schale at museumkrems opens in March 2022. What can we expect?

I have selected objects from the museumskrems collections and I combine them with my works, creating a dialogue. I want to surprise the visitors so that they enjoy it and don’t immediately forget what they have seen, but just have a good time with art.

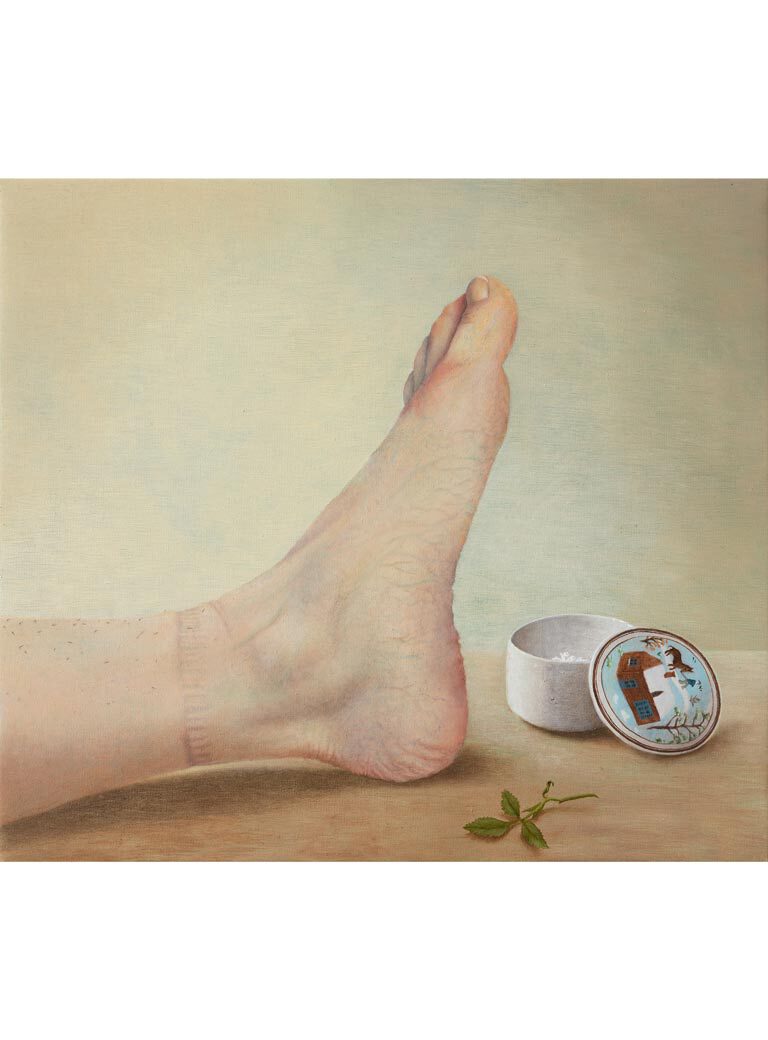

Haruko Maeda, My foot and my grandma in a ceramic ware, 40 x 45 cm, Oil on canvas, 2020

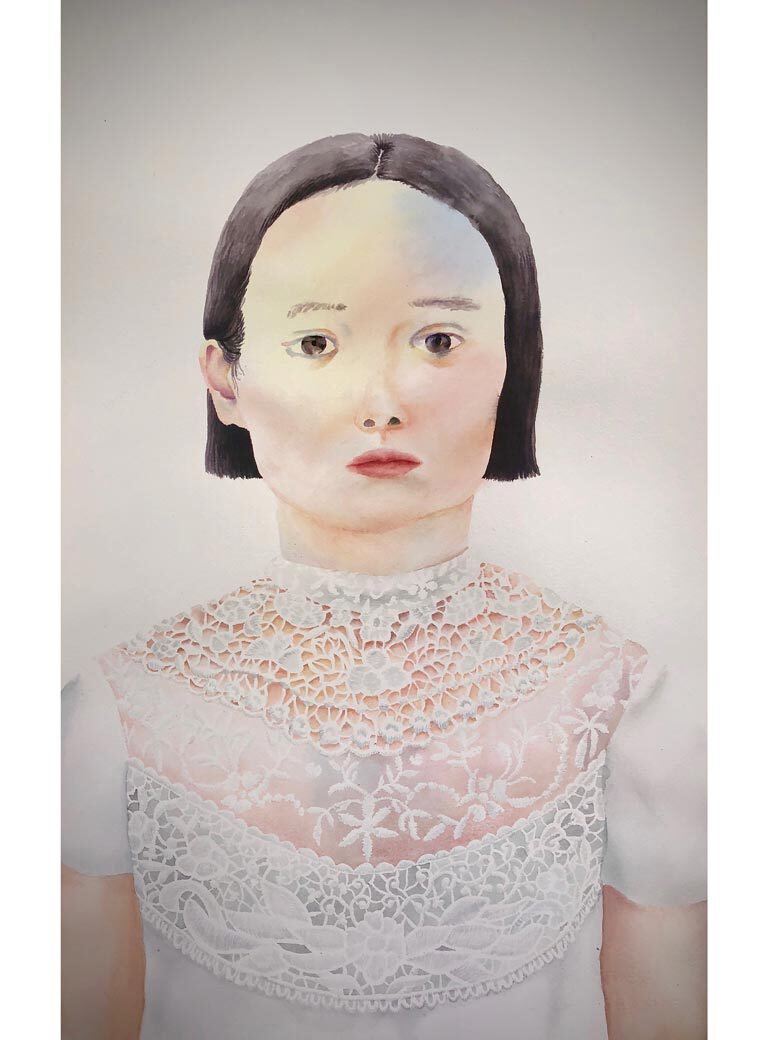

Haruko Maeda, Isolate fashion show, 56,5 x 34,5 cm, Acrylic on paper, 2020

Haruko Maeda, Neverland 5, 210 x 190 cm, Oil on canvas, 2021

Haruko Maeda, Renaissance 2, 43 x 43,5 cm, Oil on wood, hand made wooden frame, 2017

Interview: Marieluise Röttger

Photos: Maximilian Pramatarov