Heimo Zobernig's work is characterized by a reduced formal language that often has a handicraft character. The framework conditions of art are always called into question. Zobernig has developed his own color theory and also creates his own set of rules in other respects, which wants to reveal everything and enigmatize nothing. In many of his works, the artist deals with language, which is translated into simple script and often shortened to a logo. At the 56th Venice Art Biennale, Heimo Zobernig's equally radical and ingenious deconstruction of the Austrian Pavilion was much acclaimed. We met him in his studio in Vienna, where we spoke with him among others about his years at the theater, whether one should prepare art students for the art market, and about Vienna as an art metropolis.

Last year was quite an exciting one for you. You participated in the Venice Biennale staging the Austrian Pavilion. That must have been both work intensive and emotionally quite exhausting.

Yes, last year was very exciting. The days preceeding the Biennale and the Biennale itself were truly exhausting, because people expected me to answer many questions. The management of the Biennale wasn’t really a problem because I had a wonderful, very professional team. I’ve organized larger exhibitions but there is usually less hype than in Venice; that is what distinguishes the Biennale. In Venice every one is interested in you and has an opinion about your work. In a museum’s exhibition things are more specific, also public perception and subsequent feedback are not as immediate.

On the one hand it is an honor to stage the pavilion of a country in the Venice Biennale. On the other hand one receives the label "state artist".

I don’t believe that one still thinks in these categories today, things have changed. The art world has very different borders. We live in a democratic society in which the label state artist no longer exists; I have never had it thrust upon me. In Austria and many other European countries the curator’s decisions are completely free and independent, and accepted by the cultural authorities, although this is certainly not true for all countries that participate in the Biennale.

Long before you knew that you would stage the exhibition in the Austrian Pavilion in the Giardini in Venice you had played with the idea and even mentioned in another interview that your concept could have been quite different.

That’s true. But these ideas were already obsolete at the time when I received the official invitation. I more or less began completely anew. However, in addition to the two large sculptural installations that form the floor and ceiling, another sculpture might have been installed in the space. It was an opportunity to realize a first large bronze sculpture that I had planned for quite some time and included the idea for the architectural conception but with the option that I could decide whether I wanted to show it or not as soon as I saw the result. For me it was clear from the beginning that I had to have this option until the end.

What would have changed for you?

Had this bronze sculpture been additionally installed in the pavilion, it would have been clear that the conception was about this sculpture, but that was precisely what I did not want. It was Yilmaz Dziewior, the curator of the Austrian Pavilion, who adhered to the idea of adding the bronze sculpture the longest, but eventually it was installed at Kunsthaus Bregenz where the interaction of the intended relationship was possible because the bronze sculpture and the black object were placed at some distance from each other. The figure looked towards the black cube so that a similar situation resulted as in the Mies van der Rohe Pavilion in Barcelona with the Georg Kolbe sculpture.

You are an artist who develops very concrete concepts that determine precisely how a project is to be realized in an exhibition space? Which role does the curator play in your case?

While it is certainly important for an artist to develop clear concepts, one may possibly underestimate all the other necessary conditions that have to be coordinated for an exhibition to be successful. This is the curator’s achievement. Curators are very important and helpful as partners in the dialog when discussing the work.

Interviews with you began in 1977 when you moved from Kärnten to Vienna. What happened before that?

The wish to move to Vienna! I visited Vienna for the first time when I was in fourth grade. At the time it was customary for students from the city to spend one week in the country and for students from the country to come for one week to Vienna. When we stood in front of the Art Academy at the Schillerplatz in Vienna, my teacher who was also my German, drawing and sports teacher said, “One day Heimo will study here!” The next day, we stood in front of the Technical University at the Karlsplatz and he said the same thing. That irritated me because I wasn’t sure if he had forgotten what he had said the day before. Eventually he was right, I did both; at age fourteen I went to a school for machine engineering.

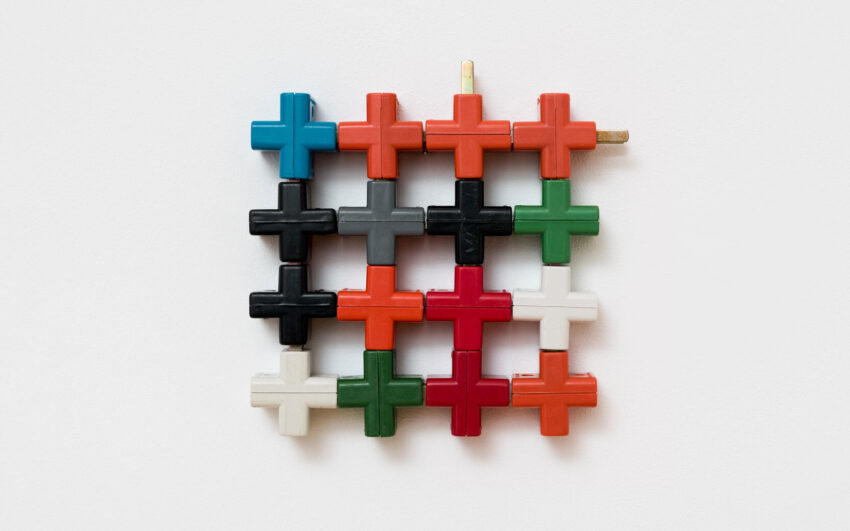

Installation view 3rd floor, Kunsthaus Bregenz

Photo: Markus Bretter, © Heimo Zobernig/Kunsthaus Bregenz/Bildrecht, Wien, 2015

Before you studied art you studied set design?

That was not really my intention: it was something of a detour because I was not accepted into a painting class. I was interested in literature but literature was not offered in other study branches, however theater set design was offered, I found it to be congenial. There were many who studied set design and did not, like myself, appreciate the theater that much. I may have only been in a theater twice before that.

You didn’t find access to the theater through the theater per se?

No, certainly not out of love and passion for this art form, because the two times while I was in middle school did not inspire in me a passion for the theater. Yet I turned relatively quickly into a theater person, because everything that happened at the time was very new and interesting. The theater of the 1970s was quite avant-garde. Much was in movement at the time and one anticipated from the theater that the visual arts and performance would develop a new art form. However, as we now know it did not quite develop that way. I have worked early as an assistant for various theaters and I soon had the opportunity to create my own stage sets. At age 23 the city of Frankfurt invited me to the Schauspielhaus for really spectacular plays like Heiner Müller’s Quartett or Peter Handke’s Über die Dörfer. As a young artist you could not have imagined anything better. But very quickly I found out that I did not want to do this over a long term. With some foresight I believe, I therefore decided to stop the theater work. I am quite certain I would not have been taken seriously as an artist otherwise.

Your teacher prophesied that you would study art. Was there ever a specific time when you realized that you would like to earn money with art, to support your life with it?

During my studies and also afterwards I did not think about such existential things. There were scholarships and promotions to apply for and on which to survive. That still exists. At that time we didn’t have much money, but I‘ve never felt it. On the contrary! I have felt very rich. When I created my first public work together with Alfons Egger in the Dramatic Center in Vienna we were asked how we intended to realize it, were we the sons of millionaires? We had just done our work and not thought about things like that. We researched the right institutions and addresses that would be prepared to provide support to us and we were able to realize what we had intended. However, not-doing was rather the thing to aspire towards at the time. Vienna’s art scene was quite transparent, a few intellectuals and artist-bohemians. The highest art was to be clever and to be able not to reveal oneself by somehow having to sell something. Not-doing was the highest art.

You’ve taught in Hamburg and Frankfurt am Main. Now you are a professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. In comparison to the earlier part of your career, how have times changed today?

Everything has changed radically! There is no comparison to how national and regional art once was and how international it is now. When I began to teach, the predominant language in the classroom was colloquial German, today it is English. Education too, has changed tremendously. Since its foundation, there has always been an extensive theoretical education –philosophy, mathematics, geometry, and similar disciplines have always been taught, but in recent years, theory and history have been greatly extended. The range is now fantastic. These days we actually have to watch that the artistic practice stays remains as the main subject.

Has the relationship between professors and students changed?

Yes, the hierarchical distance between students and teachers is not as great as I have experienced it in the past. During my time one was happy to leave the academy and go where one could receive a true response to what one was creating as a young contemporary artist. Today teachers and students understand each other so well and the students feel so comfortable that they don’t want to leave the academy. As might be expected, revolt is no longer intrinsic to the academic experience.

One may get the impression that self-marketing as an artist or thinking in terms of market strategies during training is playing an increasingly bigger role. Is this impression deceptive?

Yes, it is deceptive. I experience my students rather as interested in cultivating the improvement of the quality of artistic thinking and practice. In the process of speaking about what one is doing communication plays a big role. This was not the case thirty years ago. During their education, architects for example are taught how to speak with their clients, how to understand them and how to be able to present their plans better. That is exemplary. However, I tell the students time and again that talking about art is very important, but that it may be wiser to say nothing at the right moment. The artistic intention should be communicated primarily through the work itself. Strategies of marketing are not a complicated matter; they don’t need to be taught in a seminar.

In your opinion students should not be involved in the art market too early?

What the art market offers as a temptation or promise is not a central theme for our education. It is rather about finding out what one wants to do in order to build an existence that is based upon solid artistic work, or one will have difficulties. I consider it very important, that during their years at the academy students have the freedom to find out what they are capable of, to compare themselves to others in order to see whether what they are doing may be enduring. And that is exactly what the students want to know and experience: - the development of a work in which they can believe and which is relevant in the discussion.

Have you ever doubted your decision and questioned art?

No never! I have always felt it to be right. To this day, I can truly say that making something is really magnificent. When I was young it was not that important, I mean the making, at that time I thought more of being. From early on my life plan was to be able to determine my obligations myself and now it is so: I make and I have the freedom to wait for the indication that shows me what it is I want to make, but do not have to.

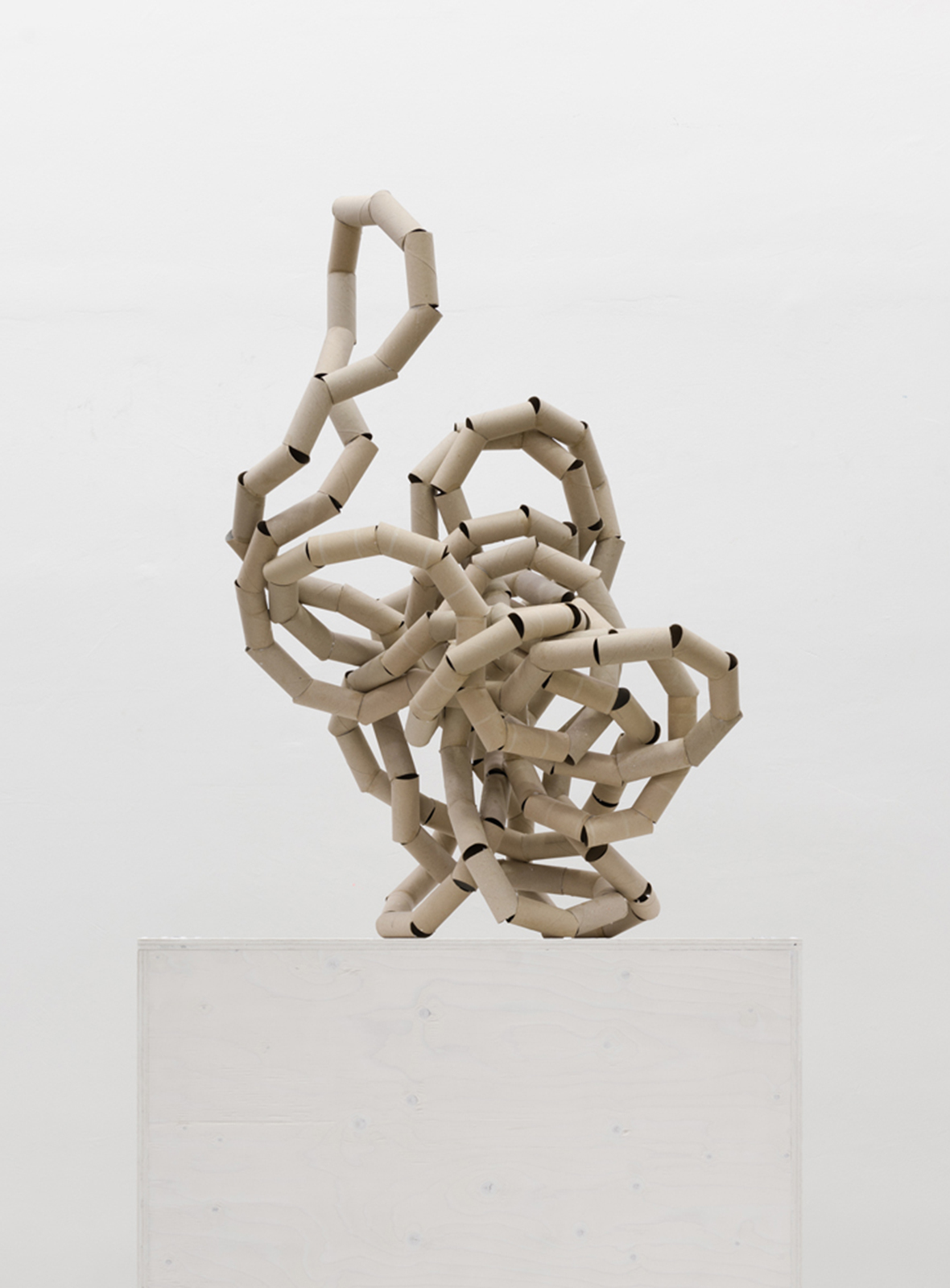

Heimo Zobernig, untitled, 2014 (detail), Cardboard, wood glue, synthetic resin varnish, plywood, 215 x 88 x 77 cm, Courtesy of the artist, © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2014

Have you ever doubted your decision and questioned art?

No never! I have always felt it to be right. To this day, I can truly say that making something is really magnificent. When I was young it was not that important, I mean the making, at that time I thought more of being. From early on my life plan was to be able to determine my obligations myself and now it is so: I make and I have the freedom to wait for the indication that shows me what it is I want to make, but do not have to.

You often work with simple, cost-effective materials – even cardboard or plywood. Is this based on pragmatism or is the choice of material only a means to an end?

That is not easy to answer. If it hadn’t included the provocation not to use the traditional materials of sculpture I would probably not have tackled it the way I did. Sometimes I was convinced that there was also an ecological component involved that I still find exciting as an ethical component of the trade. But art can’t be determined by these aspects as one cannot answer everything that results in questions. Material is always a means to an end. It is the medium of what one wants to realize. In the early days I often used to build in a model-like way. Model building materials have a rather transient character. One achieves results faster or immediately. Perhaps that has something to with the impatience to achieve quickly what one wants. To build something solidly and with an expensive finish naturally takes time – and it must be paid for.

Are you impatient?

Well, to wait for a long time until something is finished that is … (laughs) … one way or another. Patience – I do have it. I have made sculptures from toilet paper rolls. Sometimes that took two, three years before I felt they had reached a sense of completion. I started with one roll and had no idea where it would lead. The first roll I let turn to the left, the next to the right and this went from one piece to the next. Here the material determines the process, because the glue that I used to connect the rolls dried slowly. It could have been done faster with a glue pistol. But in this case I didn’t want to do that because it was not a suitable tool for working with cardboard.

Since you came to Vienna both art education and the Vienna art scene have changed tremendously.

Yes, that’s true. Vienna is turning more and more into a lively contemporary art city. When I came here years ago, I had no idea how the whole thing functioned, which role galleries played. At the time there were only a few and most doors were closed. That has changed tremendously. More and more professional galleries established themselves, like Peter Pakesch with whom I’ve worked with for a long time. t At the same time, producer galleries have been founded by artists who have created their own locations – so-called off-spaces. Very exciting institutions like the Depot have established themselves, they almost act like academies, organizing lectures and initiating projects. All in all, in both education and training as well in the art scene, Vienna has become much more international.

You are one of Austria’s most important artists. Would it not have been easier for your career to go abroad and to work directly in the cities in which the art market booms?

That is really not so easy since these regional centers are often very hermetic. It is not easy to make a career in London as a non-British person or as a non-American breakthrough in New York. I realized that quite early. Many of my colleagues who followed this call have failed there. If I were living in New York for example my resources might not be sufficient to exist as a successful artist. Besides, it was always very important to me to travel a lot and I have always taken the opportunity to spend time here and there. And I haven’t received a lot of attention in Austria – I’ve been much more successful abroad. When my son was born it became clear to me that I wanted to be were my family was. I taught in Frankfurt and Hamburg, but I was commuting.

You have several studios in Vienna. How may we imagine a typical workday of Heimo Zobernig? Are you in your studio every day?

I am in my studio when I know what I want to do. I don’t go into the studio and wait for something to happen. Where I have to go follows its own accord, I don’t have to think about it. I go to the painting studio because I want to paint a picture. Or I spend a day in the office or I am in school or traveling, or nowhere ...

Your publications follow one conception and therefore become part of your work.

My books are not merely documentations. I found many catalogs in the 1980s quite uninteresting and therefore wanted to create publications that had more character. In the process I learned a lot through making mistakes. I also wanted to simplify things, to liberate myself from too many decisions, therefore I decided to always use the same script. Right now a publication about my publications is in process. It was a tremendous amount of work: to get out all the books, to photograph everything with the accompanying small texts.

You work a lot. That is the impression. Where do you get the inspiration?

I am quite surprised that I give this impression. My inspiration as well as my recreation derives from the excessive demand as well as from the condition of exhaustion that comes from both extremes: It can also come from films, concerts, lectures, and of course especially books. But I also like to go to places where absolutely nothing is happening.

Interview: Michael Wuerges

Photos: Maximilian Pramatarov