The scene for contemporary art in Europe’s North is expanding and developing new dynamics as international collectors are watching the scene. With Nordic Notes we regularly cast the eye on the Nordic art and cultural scene, portraying its important actors.

Helena Kauppila is a mathematician turned visual artist. Her work process is heavily influenced by mathematics, neuroscience, and the observations of nature both indoors and out. Kauppila sees paintings as life affirming entities that immediately and continuously react with the viewer and the situation in space. This finally inestimable interaction, often only subtly felt, and never fully explainable through concepts or formulas, is where Kauppila finds both the allure and the worth of art.

Helena, you first studied mathematics and natural sciences before turning to art. How did you make the switch from science to art?

There were several reasons. I wanted to show what I do in my actual profession, mathematics. I always had trouble conveying to family and friends what I do with numbers, why everything is so abstract, and why I became a mathematician in the first place. And somehow the idea came to me to learn to paint and to put pictures next to the mathematics and my research so that people would understand what it was all about. I then also illustrated my doctoral thesis like a coffee table book.

What exactly is your fascination with interweaving art and science?

I love science, and it’s insanely fun for me to think interdisciplinary. Originally, as I just mentioned, I started painting to illustrate and celebrate the creativity in the scientific process. And that’s still inside me, too. I often use parts of the scientific process and translate them into my art: Pieces of data, gene modules, and many other things, but it’s not simply illustration, it’s inspiration. There are many topics in science that interest us all. We are experiencing a paradigm shift in many fields: genetic engineering, life on earth, climate change, our relationship with nature, among others. We are witnessing the emergence of many good innovations, but also many bad ones. The evolution of life, questions of astronomy... My art is characterized by a scientific view of the big picture. What does it mean to be a human being and an individual?

A very philosophical approach.

Absolutely. I think that in both art and science we are always confronted with this interplay between individualism and existence within a system. I paint alone and yet I am part of a large social system. It moves me to fathom what individual life means systematically within society. The Corona pandemic has shown that, almost everyone wears a mask in order to protect both themselves and each other. Each member of the system exerts an influence on the system as a whole. This is the essence of science and also of art, and this is precisely the question I want to explore, what happens when I as a part of society, perform an action.

Do scientific authors or other artists serve as sources of inspiration for you?

More likely other scientists! (laughs) Through my research work, when I paint, I always have a lot of scientific thoughts and the mindset of mathematics is in my subconscious. Complexity theory shapes me the most. It’s about the interaction of individual elements in the overall system. The social behavior of ants serves as a good example of this.They form a multi-layered social system and build cities of incredible complexity, all actions result from responses to chemical process, and they follow relatively simple routines on a completely intuitive basis. This is now being used in architecture as well. It’s something so simple from which so much can emerge. In principle, our society also functions according to these intuitive steps, but it is also shaped by policies and rules that contain this intuitive element.

So in your art, you’re interested in the scientific side of such complex systems.

Exactly. I find it exciting that you can model the construction of an ant city on the computer. Something like that also gives me inspiration for my art. Such ant cities are created only by small impulses, and these impulses also exist in my artistic process. It’s an interplay between the simple idea, the intellectual thought and intuition, and the question of which system I’m working in. I want to see intuitively what happens.

How does the artistic process work for you? Is it always so intuitive?

It varies a lot. My way of working can be very structured and reflective, with a clear philosophical or scientific approach, as for example in a series of works of mine dealing with genetic engineering that is currently being exhibited at the Finnish Institute. For works like Tree of Life, LUCA, and Elementary Particles, I broke down genes, decoded them and allotted each a color. It was a very systematic process. This way of working gives me a very different feeling than when I improvise artistically, which I do frequently, though. Each pigment in this painting interacts with the other. These elements from nature are non-human elements and I work with them. And in this work, I combine them with my own intuition and artistic language. In the process, something new emerges. I often paint studies first, too, before I apply something like that onto the canvas. With some paintings, this is a very long process, the research, the reflection, the painting.

How did you discover painting as an artistic language for you?

I think in colors and let myself be guided by my physical intuition. In painting I can work with layers and thereby express diversity and emotion. The layering of colors and the interaction of pigments creates very interesting, expressive art. Painting also allows me to work on a piece for a long time and change it over and over. Painting over also helps eliminate previous ideas. I have so many ideas that hide or shine in space. Painting is a great tool for that. Then, for me, it has a lot to do with the physical, the bodily. I could never work digitally. Even in mathematics, I’ve always printed everything out or written out calculations in longhand. There are so many mathematicians who detest working with computers. I just can’t think on the computer when I’m doing art. I already have so much to do with computers in my regular job. I don’t want that in my art, too. I can turn finished ideas into presentations on the computer. But the creative process before that, the brainstorming, doesn’t work digitally for me. Quite often I just draw with a pencil on paper and make little sketches.

Physicality definitely plays a certain role in your artistic work; on your Instagram account one can see dance sequences which you personally perform.

That’s right. Since the Corona pandemic began, I dance every morning before I start painting. Often just a few minutes which I then post on Instagram. I let people film me doing it to see how I feel when I paint. I’m not a dancer, but I’m all about expression in the studio. The idea of how we as people and artists capture spaces and perceive spatiality is very exciting.

Painting for me is characterized by physical movements that are associated with being a human being. I would like to explain that. It makes me feel so alive, it’s comparable to dance, in that it gives one strength. The ideas arise in my body and I want to realize them with full perception. Painting is part of expression, my works are not planned or preconceived.

Can you explain this in more detail using one of your works as an example?

I’m thinking, for example, of the images from my Berlin Parks series, like this one of Volkspark Humboldthain, an ink-on-paper work created according to the philosophy of “Emerging Systems.” I walked in this park every morning for it. In my subconscious, the idea of this park and the central, open square that I painted here emerged. In the morning the light is especially beautiful there and every day I recorded the impressions. It is not composed at all. I should have photographed this process. Here is another picture, of the Fennpfuhlpark. I lived there at the beginning of my time in Berlin and always had the feeling that I should paint there with paper. I then just bought paper for five euros and started drawing. The small lake is there in the center. I added a shade of blue every day. Again, the big system, which is shaped by the little things, the nuances.

You live and work in Berlin and have your studio in Berlin-Weißensee. What does this place do to you?

Weißensee is the perfect place to come to terms with yourself. In New York, I had studio space in the Dumbo neighborhood under the Brooklyn Bridge. That was in the middle of the city. Everything was extremely loud and churning. It was right next to the subway viaduct. Sometimes I miss those “sounds of the city” though, so I was also thinking about working more with sound. Here in this neighborhood the sounds have changed, I’m trying to explore that right now.

So the city itself is also a source for your art?

Yes definitely, and Berlin especially because it is both urban and full of nature at the same time. Again, small elements connected in a big system of the city. I’m out in nature a lot. In New York, it was the water that always exerted a powerful attraction on me. Very many works are influenced by it. In Berlin, I’m inspired by the parks and the green trees. In the current exhibition at the Finnish Institute there is a work hanging called Light Translation Device,Everyday Tree, which deals with trees and light in winter. The light has many colors and the sky is visible through the branches of the trees. When you stroll through an avenue full of winter trees, the light is refracted in a special way, and that’s what I wanted to capture with the painting.

Which work do you think has been the most important in your artistic career so far?

There are always works that are important to me at a particular moment. I listened to an artist’s discussion with Joan Greenbaum many years ago that had a great impact on me. She said that for the first twenty years she painted only junk and that it was important to let it all go and then paint well. I already like some of my early works. There are even some very early works that I like a lot and where people ask me if I could reproduce those again. I want to paint more than twenty years of junk, that’s part of my creative process. Fantastic and bad paintings are created, often at the same time. Nevertheless, I always want to be allowed to paint junk. (haha!)

Do you actually observe that you are sometimes perceived differently as an artist because of your scientific background?

Many question my work because I come from another discipline and not directly from the art world. There are somehow always people in the room asking why I make art or if I do it as a hobby or from boredom. In this regard, my residency in Istanbul in winter 2019/20 was really a super experience – to be in an environment where it was all about art. Everyone had the motto “of course art” and was open to my art. That was often not the case in other circumstances.

What images are you working on at the moment? What are your projects for this year?

I have two projects and themes. Physicality and Complex Systems. My 2011 work Complex Systems is the first in a series and has been on my mind ever since. I first encountered the term at a discussion and in googling it, discovered not just all about ants and their complex interactions, but also a recognition of the system as a philosophy of life. The relationship between members in the system and the rules we establish have always remained with me. In Berlin, I worked less on this series of works, because I keep changing pictures even over several years and wanted to devote myself to new projects here. But during the Corona restrictions, I have begun to work very much on the series of works again. There are so many ideas in it. I want to film the process now and record my body language while painting to see which painterly gestures are authentic and which are not. I think the body knows exactly which artistic intuition and the gesture that derives from it is good for it and which is not. Art is intuitive. When I rest in my body, I can paint better.

The second series I am currently working on is about genetic engineering. I started this series in 2018. Patterns, structures, and numbers are the leitmotifs. This series of works functions much more systematically, although both series remain closely connected. When I work on the systems of genetic engineering and I am painting in a large format, it is often a very physical process. If I work on it too much, my body doesn’t do well, the work activity becomes oppressive, and then I become blocked and need to switch to work on the other series. But through this physical reaction, I get the painterly gesture I need for the first series. So alternate activity on each of the project series acts in a mutually reciprocal way.

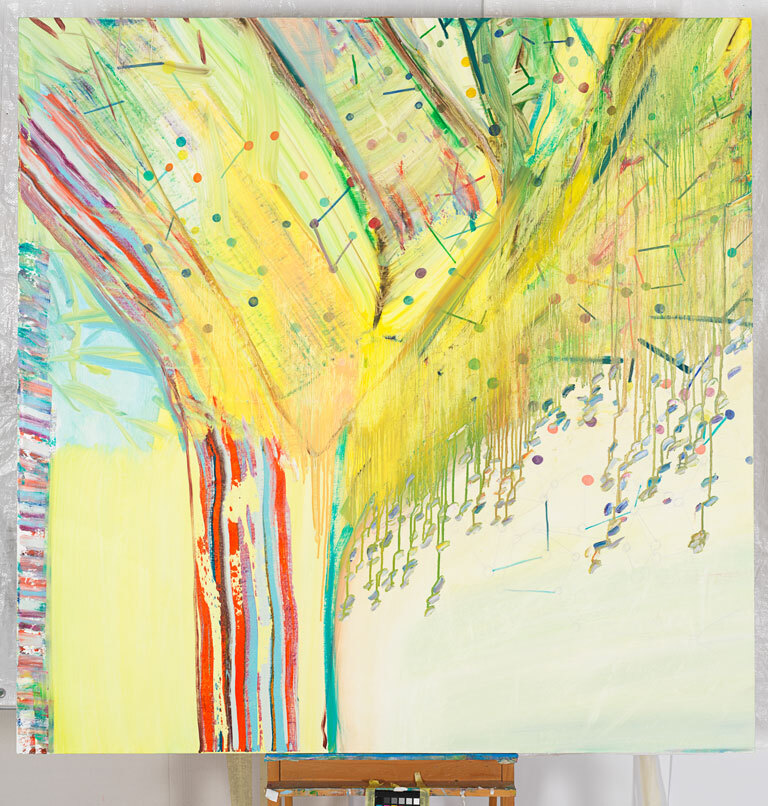

Tree of Life II, oil and colored pencil on linen, 150 x 150 cm, 2019

Photo Credits: Nick Ash/The Finnish Institute in Germany

Elementary Particles, oil on linen, 150 x 150 cm, 2019

Photo Credits: Nick Ash/The Finnish Institute in Germany

Butterfly in the Sky, oil on linen, 130 x 130 cm, 2017

Photo Credits: Nick Ash/The Finnish Institute in Germany

Humans on the Beach (ARHGAP11B), oil on linen, 150 x 150 cm, 2018

Photo Credits: Nick Ash/The Finnish Institute in Germany

Interview: Kevin Hanscke

Photos: Nora Heinisch