Photographer Hendrik Kerstens has taken pictures of his daughter, Paula, since 1995, when he left his career in business to enable his wife to return to full time work. Starting off as documentary shots, over time his portraits have become more playful and artistic: many reference works by the Dutch Old Masters, creating a dialogue between photography and painting, past and present in the process.

Hendrik, how did you first become interested in art and photography?

I wasn’t educated as an artist in a traditional sense. I never studied art or photography at a school or academy. I thought, that if you want to learn something you have to read lots of books and practice your craft. That’s what I did, and now I’m here. I always liked being busy with my hands. When I was younger, I had a friend who did beautiful ink drawings that I tried to copy, but I wasn’t very good. Instead, I became interested in cooking, which is of course very creative. I only started experimenting with visual art when I was around forty-years-old. My wife Anna and I changed roles: I quit my job in business, stayed at home, did the housekeeping, looked after our young daughter Paula, and started exploring my creative passions while my wife went to work full time. At first I thought I was going to focus on food photography, but I didn’t enjoy it as much as I might. After a while, I started taking pictures of Paula.

Many of your portraits of Paula reference and reimagine Dutch Old Masters paintings. Did you make a conscious decision to do this, or did the emulation happen organically?

In the beginning it was very intuitive. I once had a conversation with the editor in chief of The New York Times Magazine in which she told me she thought the classical style is in my blood. Being Dutch, I have been brought up to see things in a certain way, or through a certain lens. If I was Italian, for example, my photographs would have a completely different feel to them. Having said that, when I started taking these portraits I wasn’t so familiar with Dutch art history. I come from a medical family, so I wasn’t surrounded by much art and culture during my childhood. I had to teach myself about it by going to museums to look at paintings, explore their meanings, and to teach myself how to use light in a specific way. I call the Old Masters “silent teachers.” You can’t have a conversation with them, but if you look very closely you can ask yourself the question: “Is what I created good enough? Can I compare myself to them in some way?” It’s an ongoing process of learning and sharing knowledge.

What is it about the Dutch Old Masters in particular that interests you? Do you have any favorite artists?

It’s the emotion. One time, Paula, my wife, and I went on holiday to Berlin. We visited the Gemäldegalerie. I got lost and was walking by myself when I saw Portrait of a Young Woman (around 1470) by the Netherlandish painter Petrus Christus. I cried. I felt a totally overwhelming wave of emotion. It was so beautiful, it really did something to me. For me, the work was not just paint on a canvas. It was as if I could see blood flowing beneath the girl’s skin. Some pictures are completely dead, but others—like this one, and Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring (1665)—are alive. You can talk about art for many hours, but ultimately, it’s simply magic. You have to feel it. I’m happy that I’m able to channel these feelings into my own work. This said, I don’t want my photographs to be copies of Old Masters paintings, because we live in the present day. But I think, if you want to have a future as an artist, you have to respect the past. I like to compare what I do to the concept of time travel: it gives you so many different possibilities and allows you to be very free.

Can you give an example of how you reimagine or work in dialogue with the past as opposed to recreating it?

There’s a painting by Jan van Eyck in The National Gallery in London called Portrait of a Man (Self Portrait?)from 1433. The sitter wears an intricately wrapped red turban, which a lot of people have tried to imitate. I tried too, it was close to impossible. Then, I realized was working with photography, a binary system, whereas painting is a non-binary art form: van Eyck could use paint to create whatever he wanted, even things that aren’t possible in reality. So, I decided to change my approach. I photographed a basic portrait of Paula, as well as lots of photographs of the material that was going to make up her turban. I then used the computer to combine and manipulate them and overlay them with Paula’s portrait. The end result was a totally new image titled Red Turban (2015). It’s not a copy, it just takes inspiration from van Eyck’s original. It’s a very modern version of a trompe-l'œil. What Paula is wearing doesn’t exist, but it’s very convincing. We visited The National Gallery three years ago to see the original. I asked it: “Do you think I did well?” There was no answer of course, but it was a very emotional moment. It sounds a little bit silly, but I believe in that kind of dialogue. It’s not about comparing myself with the Old Masters, or bragging that I can create work like theirs, it’s about trying to understand their minds and ways of thinking.

If you could actually speak with the Old Masters, what would you ask them?

I’d like to ask them about the relationship between their artworks and their day-to-day lives. Were they interested in politics? Were they afraid of the many wars happening around them at that time? How did these factors influence their practices? Was art a method of escape for them? There was an exhibition here in the Netherlands comparing Rembrandt and Caravaggio. In my opinion, they are totally different artists because of their contexts and personal lives. Caravaggio was thought to have had homosexual relationships, whereas Rembrandt didn’t. You can see this in the work. Caravaggio’s paintings of young men are very, very, beautiful.

Many of your portraits are very playful: they feature Paula wearing unexpected, everyday items such as plastic bags, lampshades, books, and beer cans. How do you come up with these ideas? Are they supposed to be humorous? Or do they also represent deeper messages?

The photograph Bag (2007), for example, was shot after we’d spent a few months living in New York. While we were there I was so shocked to find that whenever you bought something, you were given a plastic bag to carry it in, sometimes more than one. I was also surprised by how Americans constantly had the air conditioning on in their apartments even when the temperature and humidity were not particularly uncomfortable. Global warming had just started to become a big topic in the media, but all around us people were still overusing air conditioning, heating, and plastic. This inspired me to use the plastic bag as a hat in one of my portraits of Paula. I thought it was ironic, and was trying to demonstrate that things like oil, gunpowder, and plastic can be beautiful—think of the scene with the plastic bag from the movie American Beauty (1999)—it just depends on how you use it. It’s quite amazing, because now global warming is one of the most important topics of our time. It feels like that picture is quite prophetic. Also, because it’s based on the style of the Old Masters, it feels like it creates a beautiful dialogue between the past, present, and future. My work is also about not taking life, or yourself, too seriously. When you bring things, like plastic bags, into a new context, it gives you more possibilities to dream, use your imagination, and to be free.

How has your artistic relationship with Paula developed over time? Has your process become more collaborative as she’s got older, and especially considering that she is now a qualified art historian?

I started taking pictures of Paula when she was a child because she was around me all the time. In the beginning, I had to ask myself a lot of questions about whether or not I could go public with these photographs. Can a child of six or seven really consent to having their picture distributed? It’s a big responsibility. I tried to take pictures of Anna, my wife, as well. She didn’t like it, but for Paula it’s never been a problem. I still had to keep checking and making sure she was always ok with it though, because it’s not my body, it’s not my life. She’s always free to say: “let’s stop it.” Also, now that she’s studied art history, Paula is much more educated than I ever was. She gives me a lot of historical information to support my ideas. It’s very nice.

Hendrik Kerstens, Napkin, © Hendrik Kerstens

Hendrik Kerstens, Red Turban, © Hendrik Kerstens

Hendrik Kerstens, Bag, © Hendrik Kerstens

It’s interesting that you and Paula have a very democratic approach to your relationship as artist and muse. This would have most certainly not been the case for many of the Old Masters and their female muses.

Absolutely. It has to be like this. I enjoy working with women much more than I like working with men. I feel much more comfortable around them: my whole house is female except for my grandson, the latest addition to our family. I’d call myself a feminist. I constantly ask myself the question: how is it possible that there are so many good female painters throughout history, yet none of them are included in the history books on the same level as the likes of Rembrandt and Vermeer? Today, people are getting more and more interested in rediscovering women artists from the past. There were so many who created beautiful, excellent works, such as Judith Leyster, Michaelina Wautier, Artemisia Gentileschi, and Julia Margaret-Cameron.

What about your personal, familial relationship with Paula? How has that evolved as a result of working so closely together?

Working with Paula like this is a way for me to keep my child close to me. Of course, she has her own life and mentality, but she’s always in my mind. We have a very special relationship. I feel like we’re always together. We don’t know anything different because we’ve been doing this for so long. Paula, Anna (my wife), and I are one unit. We’re like a family firm. We work artistically together, but we also have a normal life outside of art. I think it’s also very important to say that we make very clear distinctions between our artistic work and the commercial side of things. We don’t like to talk about prices or money. They are for the gallery to deal with. Maybe it’s a bit old fashioned, but I think if you do, you lose the magic. We live in magic: a magical family bubble together.

Looking to the future, what are you working on presently?

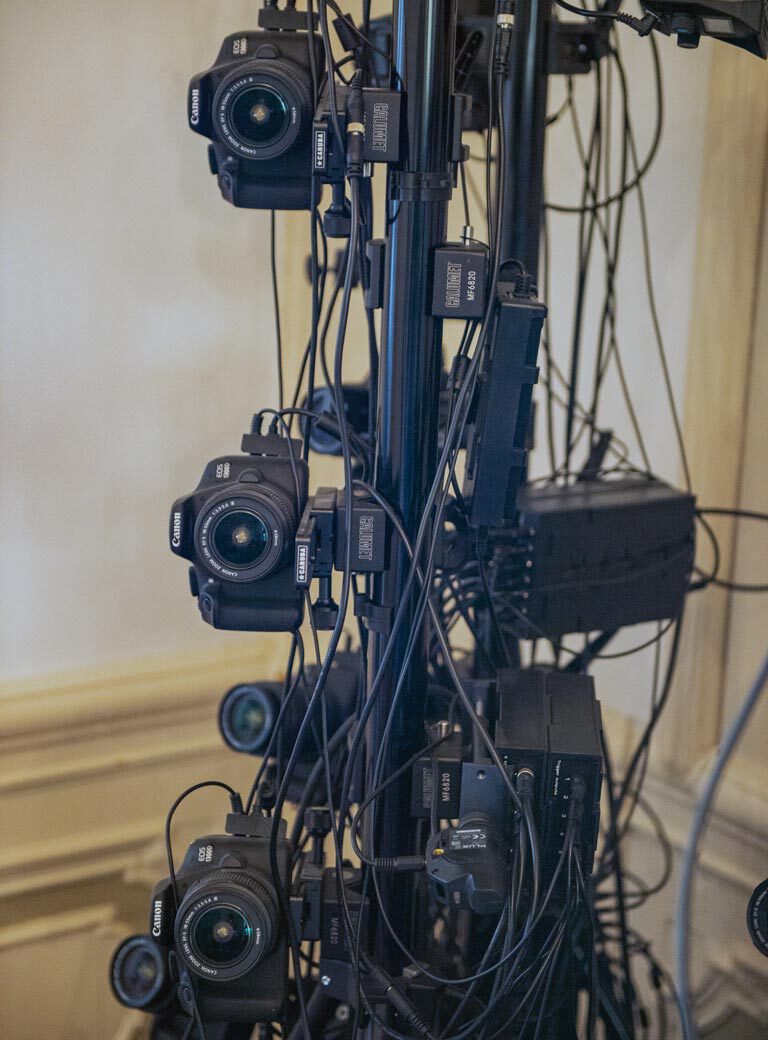

At the moment I’m really interested in pushing the boundaries of photography, and discovering how it can overlap with other disciplines. For me, medium is just a means to an end. Recently, I’ve been preoccupied with the fact that photography doesn’t allow you to see the back of the subject. The only way to counteract this is to make the image 3D. We’re currently exploring how we can transform hundreds of digital photographs of Paula taken from different angles into sculptures. We also want to combine them with clay forms, creating a dialogue between ancient materials and modern technology in the process. I’m very excited about the possibility of merging photography and sculpture in this way, even though I didn’t train professionally in either discipline.

Do you think the fact that you came to art and photography later in life has its advantages, such as being free to be more experimental?

Going to an academy when you are young makes it very easy to educate yourself. But every school is different. Some teachers really try to influence their students. In my opinion, this is quite detrimental. Not going to art school made some things a bit harder for me, but it also allowed me to be free and not be influenced by others. It can take a long time to unlearn things that teachers have forced on you and to develop your own style. This is not to say that I think that there shouldn’t be academies. Education is definitely very important. But going to a prestigious school isn’t a requirement to being a good artist. If you have the chance to go, go for it. Just be very strong. Don’t be too swayed by the people around you.

Interview: Emily May

Photos: Zan van Alderwegen