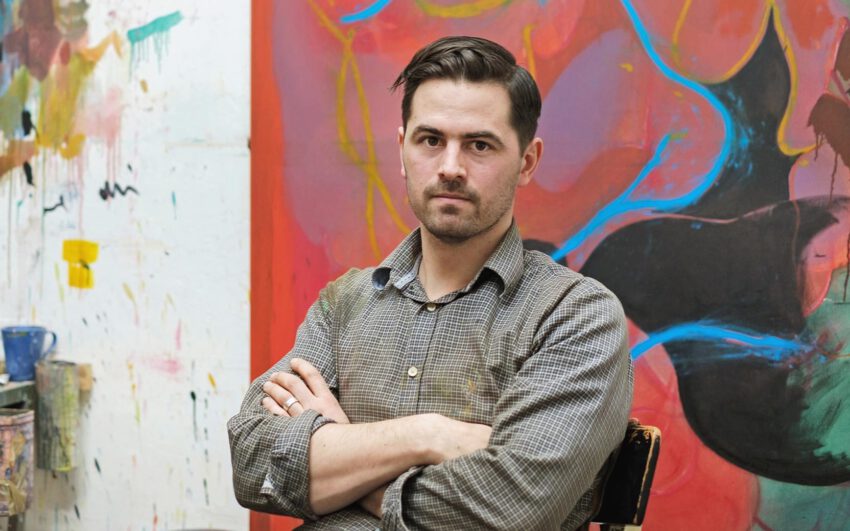

At the center of Hilla Ben Ari’s art – a reflexive and diverse corpus, created across a range of mediums, from sculpture to installation, to etching, drawing, and video – is the female body. Contorted, suffering or immobile in impossible poses, Ben Ari captures the curves and outlines of femininity that exudes a certain stoic strength, resisting both maternal connotations and the patriarchal gaze while serving as an allegory for private and collective struggles.

Hilla, your academic background is quite diverse. You studied visual arts but also pursued a theoretical degree, right? Both of these paths seem to reflect in your practice.

That’s right. I hold a BFA from Jerusalem’s Bezalel Academy of Art and Design, where I studied in the Ceramics Department. I also have an MA in Poetics and Comparative Literature from Tel Aviv University. My exposure in the latter degree to critical female theorists such as Julia Kristeva and Luce Irigaray connected me to my lifelong feminist outlook and enhanced it.

We are meeting in your home studio, which is located in the heart of Tel Aviv. But your artistic-cinematic projects are usually filmed in various locations outdoors. So how and where does the creative process begin?

My work is composed of various processes that take place simultaneously. It’s always related to some sort of research and requires a lot of reading and diving into different theoretical materials. In my latest projects, I held dialogues with the bodies of work of several artists, so the process began with research into their craft. It usually starts with a text, with an assortment of ideas and initial images that accompany me and with which I converse in my mind.

Your work relies heavily on your collaboration with performers. Could you share what this entails?

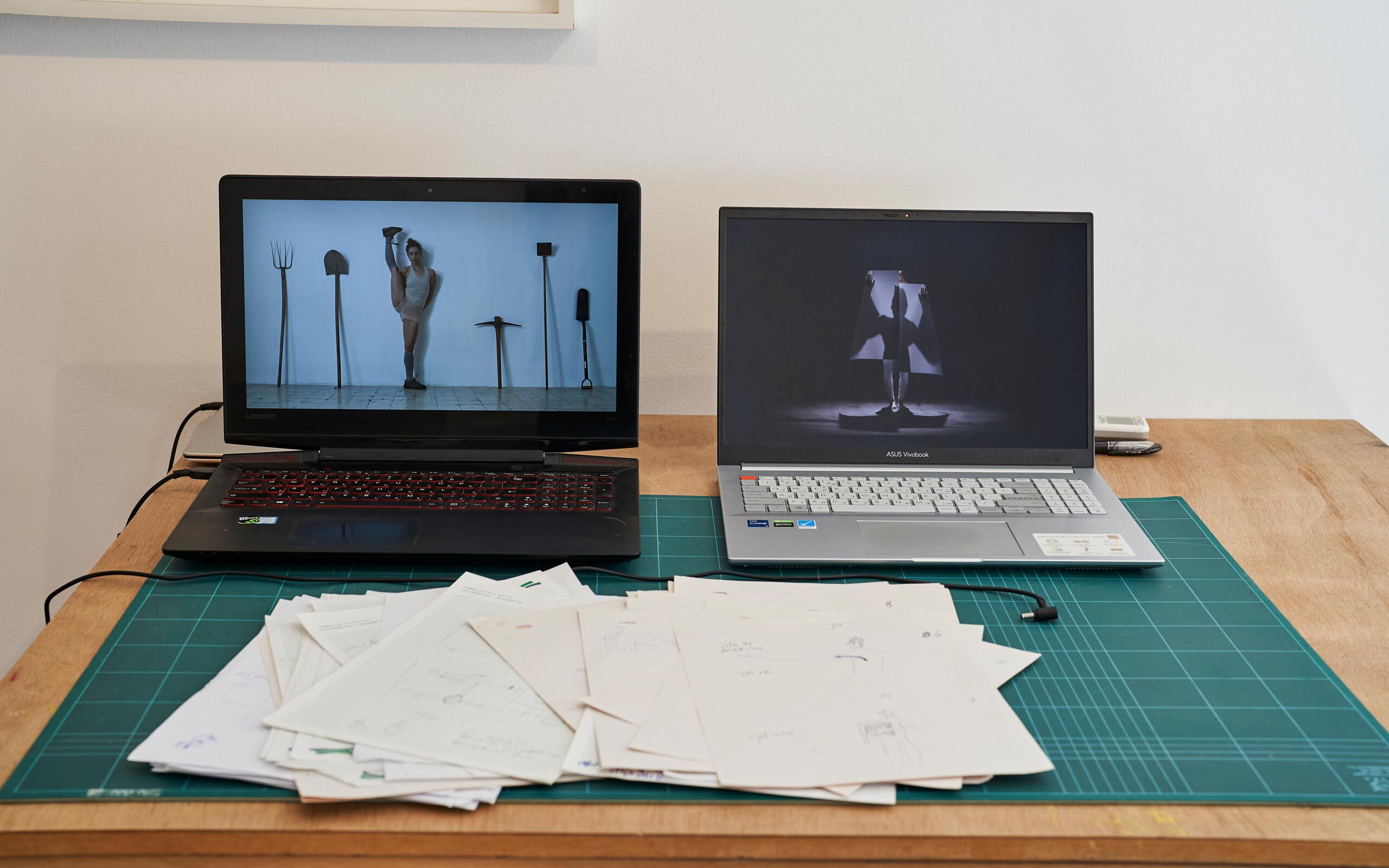

When I first started creating video works, I worked with a group of acrobats who helped me understand whether the movements I had imagined could be carried out physically. In recent years I have been collaborating mostly with dance artists. I plan the composition of their movements in advance and work on my computer, doing various simulations. The meetings with the dancers and the rehearsals come in a later stage of the process. The previous studio I had, in which I had worked up until a year ago, was a large loft that would at times magically transform into a rehearsal studio for dancers. For the rest of the time I lived there, worked and spread out big tables on which I did my art in other mediums, such as paper. I currently work from my apartment, so the rehearsals now take place in the studio but also in the living room, where I spread out linoleum on the floor and move the dining table so the dancers can move. This notion of a space that expands and shrinks very much corresponds with my art, in which I test the physical presence of the body.

So when you reach the rehearsal stage with the dancers, do you already have a complete vision of a choreography or a certain sequence of poses and movements you want them to execute?

I usually come to the rehearsals with a lot of papers on which I draw the ideas I would like to carry out, and then I show them to the dancers. When we meet, we consolidate these ideas, and sometimes they pan out differently than I had intended. In recent years, I have been approaching the notion of choreography in my craft but I was never trained as a dancer nor as a choreographer. I work in this field of movement, in which I am embarking on my own quest, without quite knowing what the normal work methods are.

What kind of relationship do you establish with the dancers? Granted, the individuals you work with possess virtuosic physical abilities, but you make them face considerable bodily (and therefore mental) challenges.

Throughout the years I have worked with different performers, and was fortunate to forge a connection with all of them. My collaborators immersed themselves in the research I opened up to them with complete dedication and devotion. Each and every one of them comes into my projects speaking a certain movement dialect, and in the encounter with me they implement their languages into my work. It’s quite fun; I am not a performer myself, but in my works the performers become a sort of extension of me. I was really blessed by meeting and collaborating with wonderful partners. Two of my personal teachers, a pilates instructor and a yoga teacher, had participated in my previous works. Women such as Avital Barak, my longtime yoga teacher and a curator, eventually took part in my work. These are women who have helped me with physical pains I endured and it was a very strong experience to invite them into my art.

You say that the performers become an extension of you, which naturally leads me to wonder why you never opted to create work that focused on your own body. Is your exploration of the worlds of athletics and movement really an inquiry about human pain?

Pain is inherent in the process and the result. I believe that the sheer physical presence of the body is subversive. In my works, the body acts in spite of systems that try to discipline it and which force it into certain structures. Positioning the body in those situations, I check how movement or its lack thereof can become an act of resistance. My works are always related to the body, even in the beginning when I grappled with it in my creation through more abstract terms. In my earliest works, the depictions of the body ranged from a dancing body to a body undergoing crucifixion. It expanded over time, and I started working in the medium of video art when I realized that I was occupied with stagnant motion. I was interested to see what would unfold when I used a moving image to depict non-motion, and to find out what could happen in the encounter between those two extremes.

When in your life do you believe that a fascination with the body began?

From early childhood onwards. I was born with a certain impairment in my legs, which I’m not sure was exteriorly visible but which I certainly felt. It wasn’t merely a physical challenge but also a social and emotional one. I grew up in a kibbutz, in a society in which the body was supposed to be this performative tool that is used to express ideology and ideas. The Zionist body had to be a strong and healthy body. Since the body was given such an important social role, I had sensed throughout my childhood that my own body represented something else, and that caused unease.

Your works often require the dancers to hold completely still in difficult positions. There is something very emotionally revealing about the static human body. Is it the physical and mental vulnerability that you are trying to shed light on?

Beyond the physical strains or the pain the dancers sometimes endure, I believe it is exactly this state that they find interesting. I am not asking them to dance, but rather to stay in place. In the same way, if you listen closely to the soundtrack of most of my works, you will realize that it slowly stretches out. In a sense, the composer I work with (Yoni Niv) asks the musicians who collaborate with us not to play music, to almost hold still with their instruments.

The role of the body in your work, and your role as its orchestrator, have developed as your body of work grew. From video loops depicting a frozen body, your latest video installations display bodies that are more fluid and expressive. Does that make you more of a choreographer, or a visual artist deeply focused on the representation of the body?

As far as I am concerned, I am deeply immersed in visual arts and that’s where I come from. This expansion in my research that has happened over the years is exciting, because I couldn’t predict it would happen. What I can say with certainty is that the body has been occupying a central role in my work across various mediums for many years, even when I was a student. I define myself as a multidisciplinary artist.

This multidisciplinarity is important for me because it enables a constant testing of boundaries and possibilities, while still working with the body and examining it in a very controlled manner. By working in different disciplines, I try to dissolve these limits.

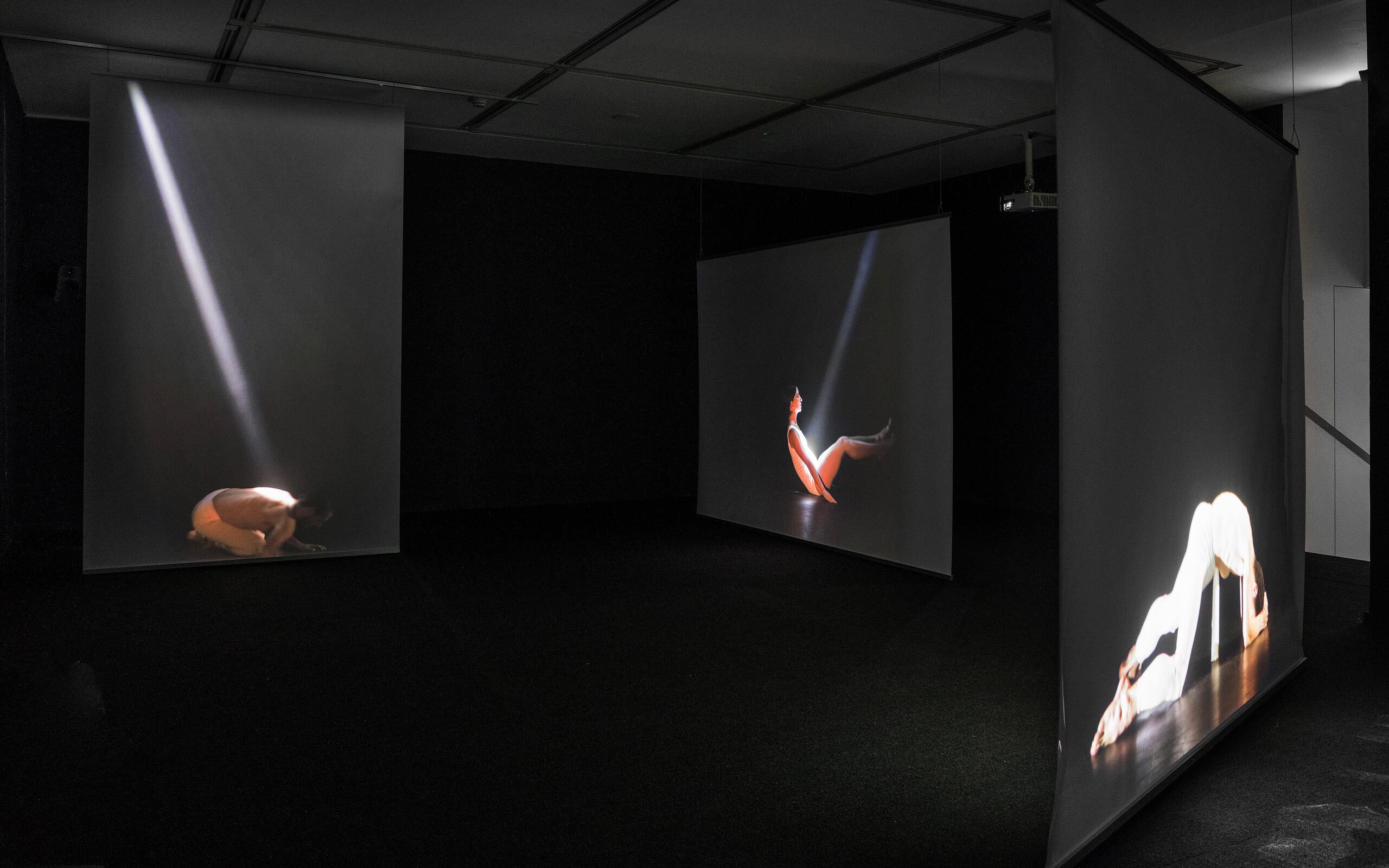

Hilla Ben Ari, The Voice that Calls to Itself, 2021, multi channel video installation, Photo: The Israel Museum Jerusalem by Elie Posner

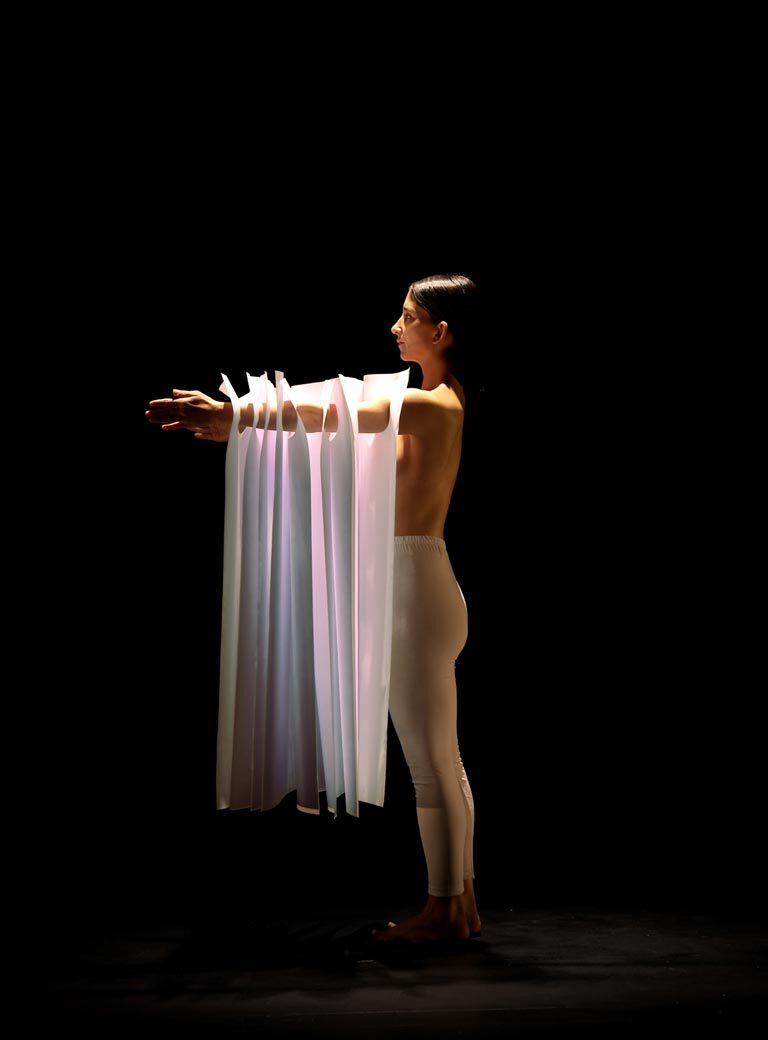

Hilla Ben Ari, The Voice that Calls to Itself, 2021, from the video, Photo: Uri Ackerman

Hilla Ben Ari, The Voice that Calls to Itself, 2021, from the video, Photo: Uri Ackerman

Hilla Ben Ari, The Voice that Calls to Itself, 2021, multi channel video installation, Photo: The Israel Museum Jerusalem by Elie Posner

Another significant theme in your work is the silence imposed on the performers. You shared your motivation and thoughts about this silence in a text you wrote for Israeli art and culture journalMaarav. Titled Between Muteness and Speech, its opening lines were: “Is a gesture mute or does it have a voice? I wish to propose a notion whereby a gesture maintains a paradoxical bodily state of muteness and speech.” Why are you so drawn to the silence and the static gesture? How are they linked?

The static aspect is related to pain and to the body’s inability, its constraints. In the text, I wrote about it as a state of disconnection and disassociation. The body carries out a kind of performance of trauma, while the soul is safe. The body is not necessarily alive, it’s like a kind of facade. The silence of the characters in my works reflects the choice not to take part in the system. It’s my attempt to say that I don’t participate in the general narrative, and at the same time I still try to tell stories.

Your latest trilogy of works consisted of a series of tributes to veteran Israeli artists. How do you explain this turn your work took, consequently giving you the role of an archivist?

By researching artists who have passed away and who may have been forgotten, I put them back in the limelight but also create through them retroactive bases to which I can return. It’s like adopting artistic mothers and fathers. I didn’t necessarily know their work my whole life, but I do find a connection with their creation. The trilogy includes Naamah – A Tribute to Nahum Ben Ari (2015), a four-channel video installation in which I proposed an interpretation to a forgotten play written by my grandfather’s brother; Broken Lines – A Tribute to Heda Oren (2017), in which I followed the footsteps of the late Israeli choreographer; and my latest project, The Voice That Calls to Itself, an homage to the deceased papercut artist Moshe Reifer, which I’m presenting at The Israel Museum’s Ticho House.

Hilla Ben Ari, Naamah – A Tribute to Nahum Ben Ari, 2015, from the video, Photo: Asaf Saban

Hilla Ben Ari, Rethinking Broken Lines – A Tribute to Heda Oren, 2017, from the video, Photo: Asaf Saban

How did you find a connection with each of these artists and their stories?

It usually starts with my own independent research. With Heda Oren, I encountered online an image of a work she created in the 1970s and was stunned. I felt such a strong affinity to her work. I then embarked on a very extensive research project. After I read through her journals, I realized I wanted to offer a new interpretation to her work and explore the issue of identity through my own means. With Nahum Benari, I had become familiarized with a play he wrote without ever having met him since he passed away before I was born. I didn’t know much about him and learned a lot about my own family through this project. When I read the play, I discovered the character of Naamah, a mute woman, and it was obvious to me that if I responded to the play then her character would become central because it echoes all the female figures that appear in my other works. The third project was based on a dialogue with the works and character of Moshe Reifer, an artist who lived a significant period of his life in the kibbutz where I grew up. The multi-channel video installation I created, which was inspired by his papercuts from the 1930s, deals with the body and mental states such as detachment and psychosis.

To cap off, I’d like to know what you are working on next. Is there a dream project in the pipelines?

Throughout the period of the COVID-19 pandemic, I have had to take a pause from planning productions and have begun working on different projects indoors. One is a play I have written and hope to stage in the (near) future. It’s still very much in its initial stages.

Interview: Joy Bernard

Photos: Shir Lusky