The Vienna-based artist Hong Zeiss first studied philosophy and then figurative and textual sculpture. His paintings are based on an intensive examination of philosophical and historical questions, whereby he traces the sensual effects of nature and how these can be captured through abstraction. Zeiss is also a co-founder of the experimental project “Peer Production”, which explores the cultural value of production in art through exhibitions.

Hong, before you came to art, you studied philosophy in Salzburg.

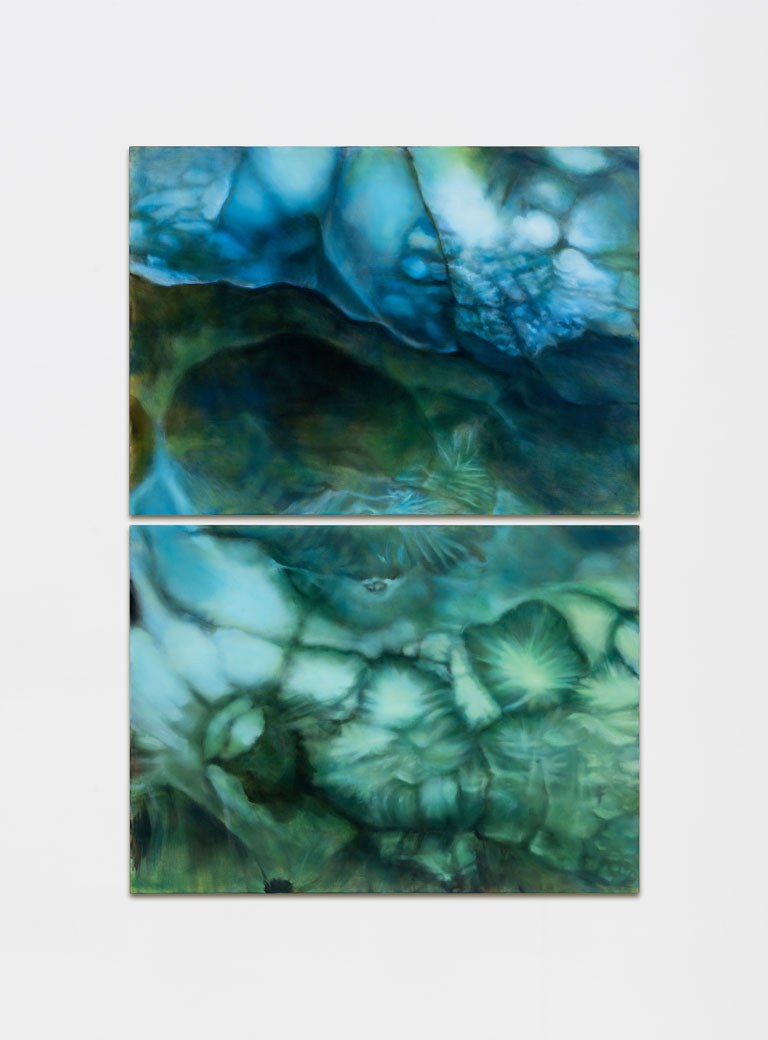

Exactly, and I also worked in the natural stone industry in industrial processing, i.e., I bought marble blocks and granite blocks from quarries. I was 19 when I got the job. Although I could have had a good career in this industry, something fundamental was missing and it changed in me. My initial drive was to become a part of the “financial world”, but once I started living in that world, I was desperate for a way out – a way out of a world of financial schizophrenia. At this point, philosophy, especially Kant and his concept of aesthetics, became crucial in transforming my thoughts. Another reason why Kant, or German idealism in general, became so fundamental to my thinking was that I saw a connection between German idealism and the Chinese Taoist view.

Were there already references to art here?

The connection was not immediate, but art soon became an activity in which I could achieve a kind of self-realization, independent of what was socially useful or replaceable. Kant speaks of disinterested pleasure, and this can be very well linked to the Chinese ideal of blandness. And blandness is what is removed from our worldly view and is then more about the sublime and the question of what is beautiful. After Enlightenment, the sublime emerged in modernity as a substitute for the divine. That sounds very theological now (laughs), but it goes beyond a formal way of thinking about what art is and what we want with it.

In retrospect, did your work in the natural stone industry bring you to Vienna to study figurative and textual sculpture?

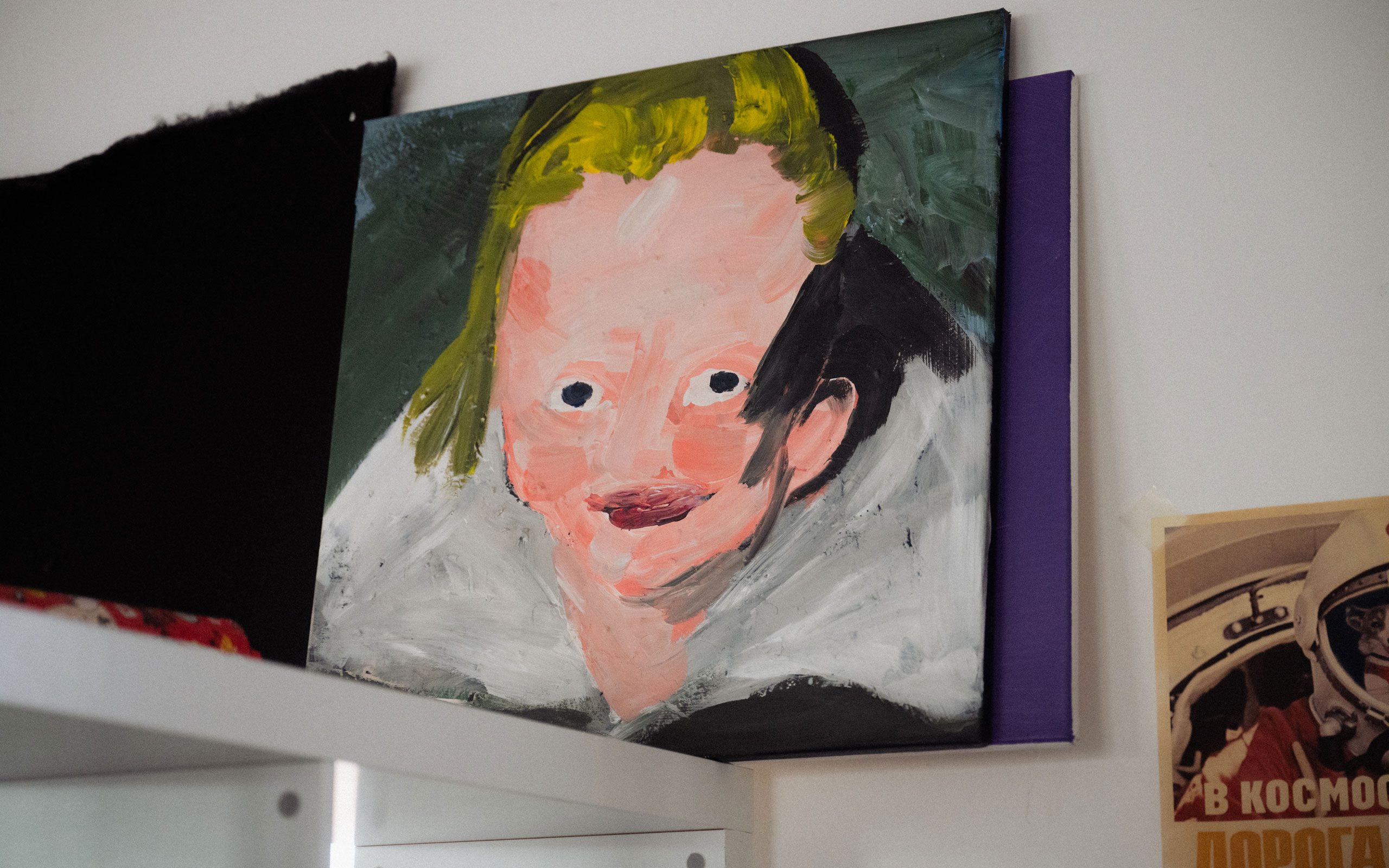

I wouldn’t make a direct connection, but there was something about the structure of the stones that fascinated me, and because the material is architectural, the sculptural was intrinsic. It's also interesting because sculpture was never an art discipline in China, it was a craft. I was not yet an artist and did not yet feel like an artist. It was a good school of seeing, because through figurative sculpture you learn to see very well, because our sensorium, i.e., our sensitivity to faces and bodies, is much more pronounced than to a flower, for example. I can paint a flower quickly and nobody will notice whether it is precise or not. But to capture a face or a figure well requires a certain kind of vision, a very precise one.

How do you feel about being an artist now?

There was an interest, also for this leap of creating, because I have always drawn and painted. One of my uncles studied painting in Düsseldorf, but I knew from the start that it wasn’t necessarily a career. He stopped and continued with real estate in China. You can’t program it and certainly not as a career. However, I tried to follow the interests and questions I had.

That doesn’t sound like there was family support for an artistic existence …

That’s true, but I earned very well in the stone industry. I have always had a job, a bread-and-butter job so to speak; I have been assisting the artist Otto Zitko for eight years now; he makes these very gestural, expansive installations. I don't have to make a living from my art. It has been going quite well recently and I am keeping it open because I am not interested in a career within the art world.

What were your beginnings in Vienna like?

At first, I studied at the University of Applied Arts with Gerda Fassl. We were only allowed to work classically and figuratively; she was very strict ... And as I said, I inevitably didn’t see sculpture as an art discipline at all, but as a craft. She was succeeded by a professor with whom I could not work at all. But in the back of my mind there was still the question of what art was, and so I transferred to the Academy. I ran to Heimo Zobernig with a portfolio of nude drawings and thought he wouldn’t say anything about it and, surprisingly, he was very, very open to me and saw a lot. The first artist he discussed with me was Joseph Dabernig, who came from classical sculpture and later became conceptual. And I was fascinated by this conceptualism, so I became more involved with conceptual post-minimalists.

And this occupation led you to painting as your medium?

That took a little longer (laughs). For a long time, I was an assistant to the art historian Sabeth Buchmann. She focused on modern art and institutional critique. And the concept of critique appealed to me; it brought me back to my philosophical roots, Kant and his three critiques, i.e., what critique actually is. I became interested in artists Andrea Fraser’s and Louise Lawler’s positions, who, in short, said that art is what defines the institution. I could have stayed with theory, but it wasn’t my medium, because this understanding of the respective position can only take place with a practice. I told myself that pointing the finger at others doesn’t work either, because one is always involved. And because of all the criticizing of other people, I thought I had to produce something myself that could be criticized, especially through painterly practice.

Why has Kant's concept of aesthetics become so important for your work?

Kant speaks of the sensual and the supersensible ... Kant’s first critique, Pure Reason, is about sensuality; the second critique, Practical Reason, is about morality, i.e., the social, which exists but cannot be experienced by the senses. In the third critique of the Power of Judgment, the sensual and the supersensual meet by means of aesthetics, where sensuality and morality unite; the sensual and the supersensual are brought together through the feeling of pleasure or displeasure in aesthetic judgment. You don’t design a picture on a drawing board, you paint and there are moments when you do it this way or that. It’s an unreflected, immediate, sensual act. And when you reflect on whether you're doing it right or not during the process or later, that’s the moment of ethics or morality.

A very specific reference system that you should be familiar with, right? Do you think viewers see this?

No, not necessarily, it depends on the viewer. In principle, I like works that communicate through their aesthetics, there are ethics and politics in aesthetics, that's what I believe. Like the unconscious in the psyche.

So, you deliberately leave it open as to what triggers your work?

I prefer not to say anything at all. So, if someone sees it and says, okay, successful composition, I think to myself: yes, of course, approved by Velázquez and Cézanne. And if it’s a bad composition, it's not my fault. (laughs)

How do you start a painting?

I start very gesturally, with an umber underpainting; as an underpainting it can be very neutral, i.e., I only operate with the color value, light/dark, and not the color quality. So I only think about the structure, because if I do color and structure at the same time, it's more strenuous. And then I work with light glaze layers on top; I glaze in RGB colors, first a pure yellow, then a pure blue and then comes red, and then comes white and then comes blue again ... depending on how I paint the pieces, and that’s how the glazing effects are added, because they are no longer pure colors.

If we go back to the sensual, what role do colors and textures play for you?

That’s the taste we’re talking about. I choose according to how I feel, and I’m attracted to motifs. It can be both. It can be that I find an artist really great, like Georgia O'Keefe, and then I often adopt the technique so that I understand why certain painters have painted things like that; what's going on inside them, or why they like it, and when I understand that I try to imagine why they like it. O'Keefe once said that the blow-ups she makes force her to find a painterly solution, an abstraction, because otherwise it would be photorealism. You can see that it’s not photorealism in my case, because otherwise I would be painting crystals. This compulsion to abstract brings me into painting.

What drives you to continue with art?

I think sometimes it's so nonsensical that it makes sense again (laughs). That it’s not corruptible if you stick to it. Why disinterested pleasure, it’s for the sake of autonomy, because if there’s interest, then it’s corruptible by other interests besides itself. And to come back to the Asian, the Taoist, emptiness serves as the aesthetic basis from which it arises.

You were born in Taipei, grew up in Germany and studied in Austria ... Now that you live and work in Vienna, what does the city offer you and will you stay?

In Vienna it’s the peace and quiet, the boredom ... (laughs). There’s nothing new happening all the time. I need that to work, the contemplative and the out-of-time; you really fall into a time hole here, especially where my studio is. You can spend days here. I also find Shanghai or Taipei nice places to live, but I would probably just go out to eat there all the time (laughs). But yes, I need seclusion for the things I do, and that’s what Vienna is for me.

What projects are coming up, what can we look forward to?

I am busy painting!

Exhibition view, Copyright: Laura Schawelka

Exhibition view Misstrauen, Copyright: Simon Veres

Vienna Contemporary, Copyright: Simon Veres

Exhibition view Misstrauen, Copyright: Simon Veres

Interview: Marieluise Röttger

Photos: Christoph Liebentritt