Huda Takriti was born in Syria, where she studied art at the University of Damascus. She later continued her education at the Transmedia Art Department at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna, where she is still based. Working as a trans-disciplinary artist, Takriti uses video, film, installation, painting and performative situations to challenge traditional perceptions of history and politics. Her work resembles a collage, where the connections between more personal memories and the history of the Middle East are intertwined, offering new views on colonialism, feminism and memory.

Huda, what made you decide to become an artist?

Well, as a child, I was always drawing, and my Mum enrolled me in a drawing course – which I carried on doing until I was 18. At this point, it made more sense for me to go into art studies than anything else! If it had not been art, I guess it would have been mathematics.

What was your experience studying art in Damascus like?

Thinking back, we had one young professor who had studied in France for a while, and she was the only one working with installation and video. All the other professors were 80-year-olds who had studied in the Soviet Union, with a specific idea of what a painting should be. However, I had already started to be interested in video much more than in painting. But, as installation and video were not considered “art” for these professors, I realised that there was no chance for me to delve further into these mediums at my university.

Civil war broke out in Syria in 2011, while you were at university. Was there a disruption, a change, a sense of politics coming into play?

Of course, it was the beginning of some highly charged political years, and it affected every aspect of life for everyone. I felt the need to go back to the history and the political formations in the country, to better comprehend what was happening and how we had reached such a stage. The further back I went, the more I could see how the uprisings during the “Arab Spring” are interconnected. This was a point that helped form my interest in the history of the region, and it started to reflect on my work.

You then left Syria in 2016?

Yes, I had been to Austria on a residency in 2014 and had heard about the Transarts department at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna. I took the entrance exam and this subject seemed, in my view, to contain everything that I was missing in Syria. There, you just learn how to paint.

Isn’t that important too?

Absolutely, and I am very grateful for what I learned there. It was also mandatory for us to take art history and critical studies courses throughout the four years of study. I feel my painting background is reflected in the way I work on the compositions for my videos and in the way I piece everything together.

Regarding your work: how do you get started? Where do you find your inspiration?

My work always starts with personal encounters, with someone telling me about something. For instance, there is one work I did in 2016/2017, and my starting point was this well-known Arabic song about Vienna from the 1940s – how it is heaven on earth and so on. It is sung by Asmahan, a Syrian diva who had never even been to Vienna, nor had the songwriter or the composer! But it is so famous that even a young boy started to sing it for me once he realized I was studying in Vienna. This encounter got me started: how could a child know a song from the 1940s and have this imagination about Vienna?

And to what work did that lead?

To a site-specific video in 2018 called The Euphoric Nights in Vienna; Here and Elsewhere, the first part of the work’s title is the title of the song. It comes from a musical film; the set has a Viennese palace in the background, and the actress is walking around and dancing a waltz and singing about how great Vienna is. So, I cut her out of that video and filmed the background again, which was coincidentally the building of the University of Applied Arts where I was studying at the time, and then I implemented her there. The contradiction in my piece revolves around the place she sings about, the Vienna I know and the exhibition location.

Another source of inspiration seems to be your family history?

Yes, because I am curious about it; my Mum had always told me so many interesting stories about her family, and they are all centered around specific historical and political periods that I am interested in. For instance, my grandmother, Hikmat Al-Habbal, was an artist doing weaving and tapestry and working as a fashion designer and an Art teacher in Kuwait in the 1950s and 1960s. But when she moved to Syria, her work was discarded as “just craft,” and she was never able to show it there. Today, there is only one finished artwork of hers left that my Mum still possesses, along with many unfinished pieces that she takes care of. My grandmother intentionally left some pieces unfinished, hoping that my mom or us, her grandchildren, would complete them. So I am currently working on a piece where I explore the possibility of completing these works – in my way, of course.

How did you do that?

I am working on a two-channel video installation in which I combine the personal and the political. I show my Mum taking out these unfinished, fragile works. At the same time, I present photo albums that trace my grandmother’s moves from Syria to Lebanon to Kuwait. At the end, by interweaving my grandmother’s work with the photos, I show how it all connects to the history of the region. In the Arab world, everything is connected! And my family illustrates this: I think I have Moroccan as well as Egyptian relatives.

Therefore, do you feel that this personal story generates a more universal feeling?

Of course. My work is always about the intertwining of the personal and political.

To achieve this, you layer these aesthetically pleasing pictures from family albums or such with more documentary ones. How do you decide what fits together?

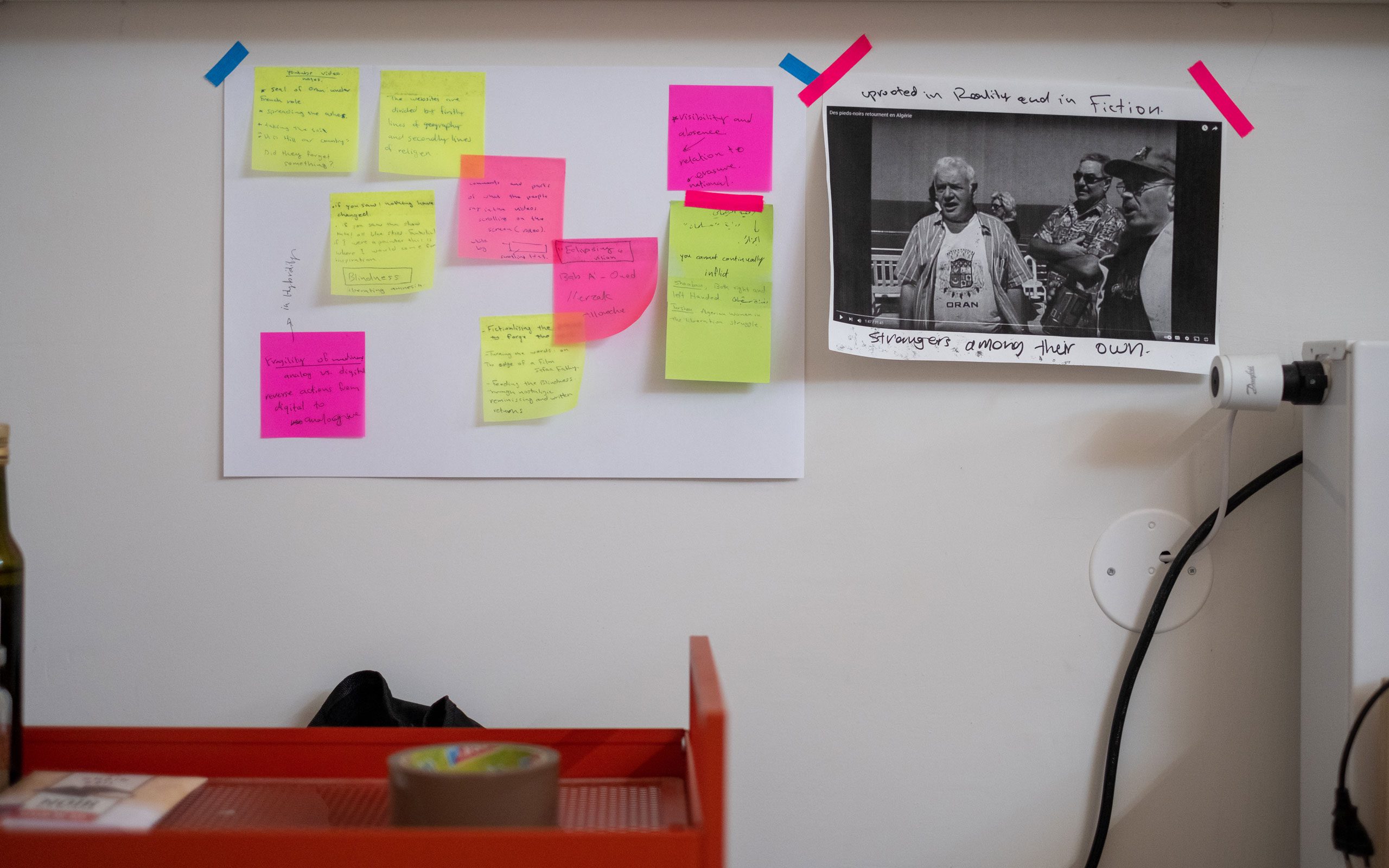

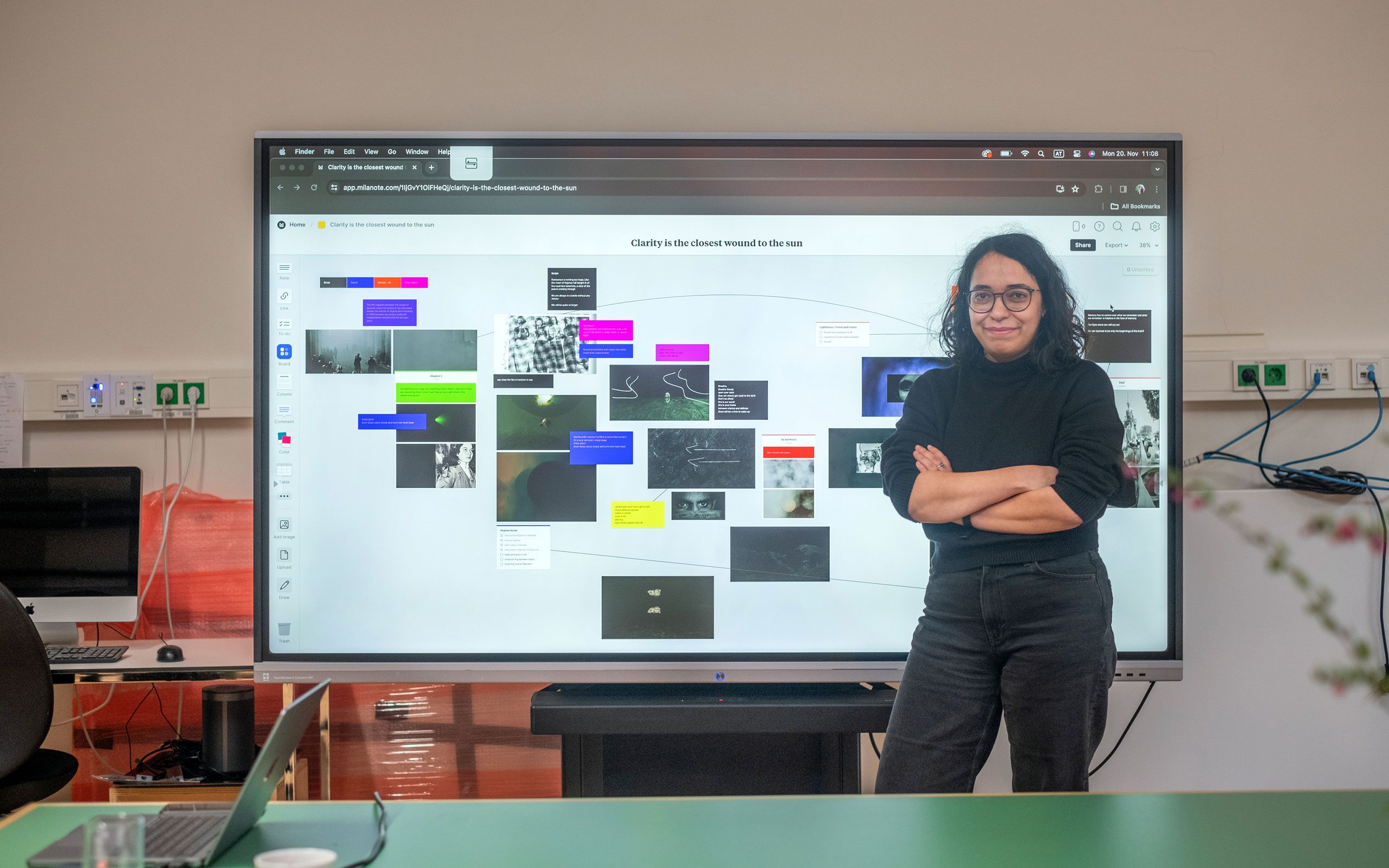

It all depends on the process. Once I have my starting point, I take my time doing the research, collecting images and ideas. Making a video can take up to two years; there are a lot of layers and connections that I want to discover and put in there! The final version comes together whilst I am editing, going back and forth between different images and making them relate to one another. I sometimes use text if I feel that the image asks for something more. My script for the video looks more like a mood board – I have it open on one monitor, and the editing happens on another.

Apart from text, do you include painting, too?

Well, what might look like paintings in my videos is made in 3D, and I prepare the sketches. I don’t paint anymore – it is much cheaper to work on a laptop (laughs)!

Some sequences in your videos feel dreamlike – is it on purpose?

Yes, and again this may stem from my education as a painter. Somehow, I feel as if I am still a painter before anything else! I always like to add a dreamlike aspect to these historical and documentary images. If I come across something dreamy or surrealistic during my research for a piece, I will probably use it.

A lot of your works center around women: a singer, your grandmother, female freedom fighters… Why is that?

Well, I grew up in a feminist household, and I always looked up to my mother; she was politically active from a young age and comes from a very diverse and political family, and she is a very naturally gifted storyteller. The stories she would tell were about inspiring female figures in her life, whether or not they were family members. As my interest in the political sphere of the Arab world grew, I always looked into what the situation was like for women and how they were involved politically throughout the years, most specifically in liberation movements such as the National Liberation Front in Algeria and the rise of the Arab Nationalist movement in Egypt and Syria. I would compare the situation with what is unfolding right now in the Middle East. For instance, the rate of homeless women in Algeria is rising. The family code there refuses divorced or widowed women any rights; their family members might not even accept them back into the household. I feel there is such a contradiction between the important role women played during the fight for liberation in the 1960s and the way the current situation has unfolded.

How do you perceive the general view on women in the Arab world?

It’s very hard to generalise it, as we are talking about different spheres under one umbrella. The experience of a Qatari woman might be completely different for a Moroccan or Syrian woman, for example. Different social and economic factors play a role. In the Seventies, during the Pan-Arabist movement, a lot of magazines such as Al-Hilal and The Arab, put illustrations of women fighters on their covers. The movement aimed for emancipation and a more inclusive future. But all those images might be considered today as aesthetics; they did not lead to a real improvement in the lives of women. I am still not sure when or how these things took a different turn. We now see the debate in the US or Poland regarding abortion laws. There is clearly still a long way to go for women in general, not only in the Arab world.

And you would like to change that?

Hopefully! Therefore, the connection between what happened then and what is happening today is important to me. Which is why I am trying to put it on the radar once again. But to me, it is not only about advancing a feminist perspective. I’m very aware of the Western gaze on the Middle East and of my own presence and work in a Western context. I want to challenge this context and introduce a non-Western perspective to these issues.

Therefore taking a stance regarding Colonialism?

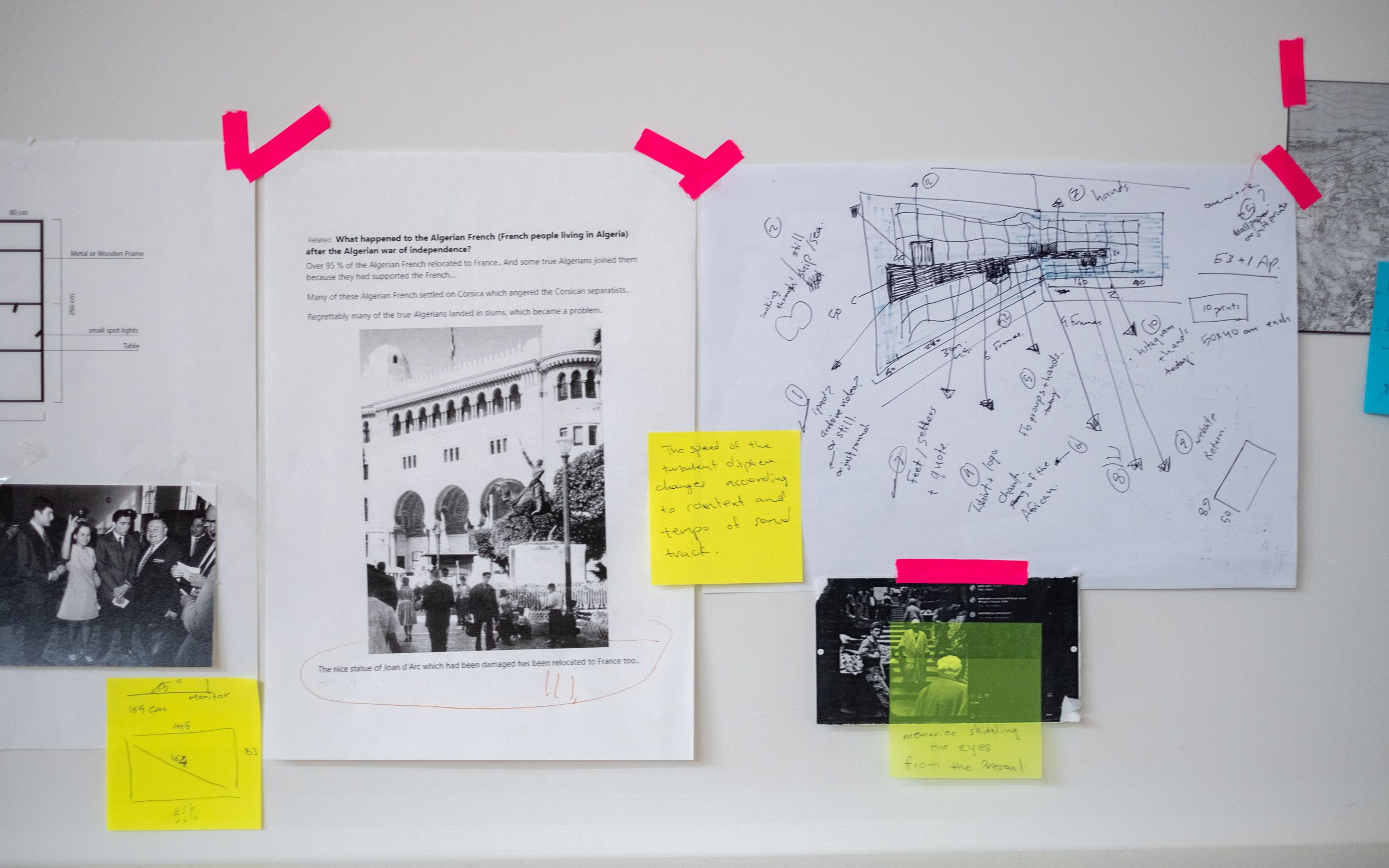

Yes, I want to point out the Western view on colonialism, and the so-called ‘oriental gaze’. Now, I am working with French archives that play into this so-called ‘dream of the Orient’ in relation to Algeria, Morocco, and North Africa. I have become very aware of it.

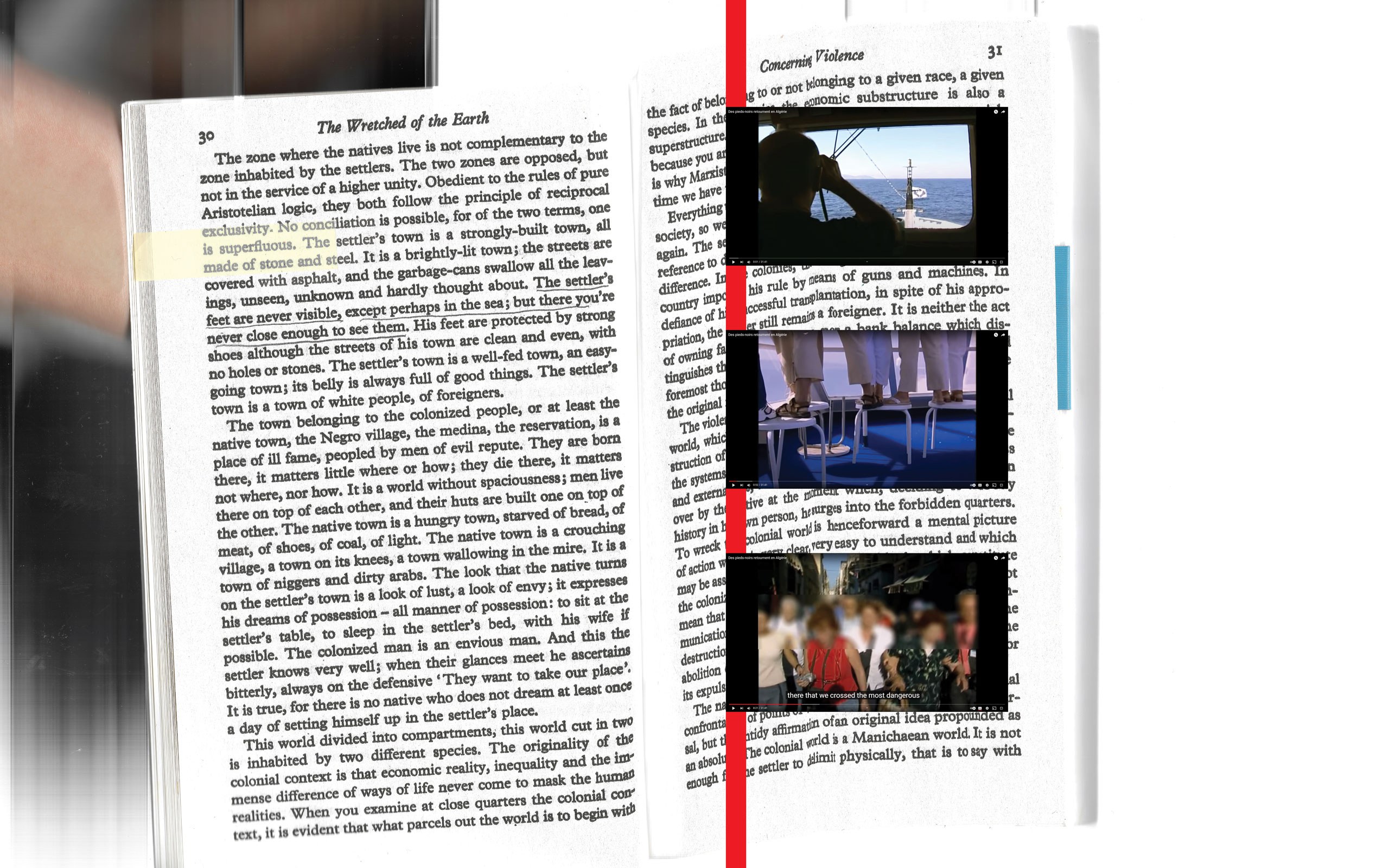

Fluid Grounds (The settler’s feet are never visible), Digital Photo montage, C-print on Hahnemühle, Photo: Rag Baryta, 2023

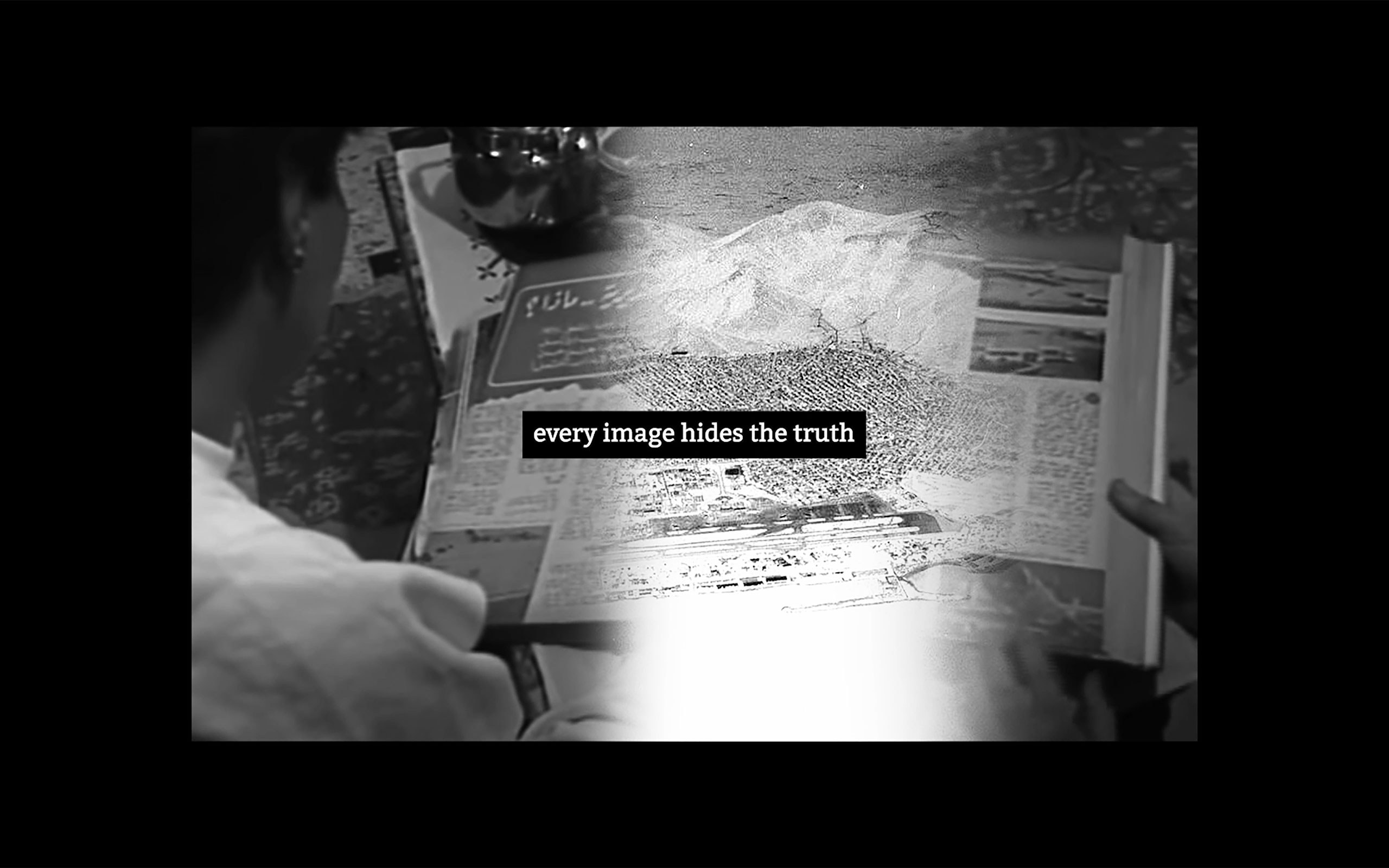

Are you generally questioning the truth in pictures?

Yes. Especially where historical pictures are concerned! But the same goes for today: Even I can take a photo from a fictional film, insert it in a documentary space, and present it as something factual. It interests me how images can tell stories and play two roles at the same time.

Do you feel that pictures have become untrustworthy?

Maybe. I guess it is related to the fast spread of photos on social media and the possibility of creating and spreading AI generated images so easily.

So, what do you think? Should we still believe in pictures?

It’s interesting to think of pictures as the holders or vessels of truth nowadays. The way we look at pictures or even create them is very different than it was 40 or 50 years ago. Of course, it was different than the way people looked at photographs in the early days of photography. I would say, from today’s perspective, that before one believes a picture, one needs to look closely and try to find the source of it! Although, even I fall into that trap as it sometimes takes me time to realise that something is edited or made in 3D and not in real life.

The Euphoric Nights in Vienna: Here and Elsewhere, Site-Specific Video Installation, Black&White, Sound, 2017

Still, The Euphoric Nights in Vienna: Here and Elsewhere, Site-Specific Video Installation, Black&White, Sound, 2017

Still, Refusing to Meet Your Eye, One Channel Video and Photo Archive, HD, Color, Black&White, Sound, 2022

Algeria seems to be a recurring theme in your work, though you’re not Algerian yourself. Why this particular interest?

It originates from the Pan-Arabist movement and its history. My family was very political; we had a lot of magazines and books about Algeria from the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s at home. The interconnection between the stories of these women in the books, some of them freedom fighters, and the history of the Arab world interested me. My work is not about Algeria as such, or Syria. The French and British mandates divided the area that used to be called Great Syria; it used to encompass Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, and Jordan. Therefore, just because I am from Syria does not mean that I don’t have historical or ideological connections to Algeria or Lebanon or Egypt. Politically and historically, it is all connected.

Your work is often centered around conflicts in the Middle East dating back to the 1950s and 1960s. However, you studied in Damascus when the war broke out in 2011… Why focus on wars that are way past instead of ones that are much closer in time?

Investigating the wars that have passed can help us comprehend the current situation. I feel the politics and policies of the regimes today are, in general, connected to what happened then. This is why I think it is important to look back. In my work, I cannot separate my present life from what has happened before. And it’s not just about me. I feel that even if you decide to paint a flower, there is something political in that, relating to your background, identity, political views, etc.

Do you think art has to be political?

Wasn’t it always? Think about Michelangelo getting commissioned by the church to make all those masterpieces. Power certainly played a role in the arts back then, and it still does today. The source of the money spent on art throughout history intertwines with the politics of the time. However, it is up to each artist to make that connection for themselves or not. To me, the source of every material available to me is political. Buying a certain coloured brand made in one country with the powder of this color imported from another is due to a political process. For me, as someone who is working with digital-based technology, I am aware that most of the tools that I need to use rely on cobalt mining in the Congo, as an example. So before jumping on the latest tech product that can be used in creating my video works, I try to ask myself if the work really needs it or if it is just a fancy addition. If it is just an addition, then I will not use it for sure. So, even if I am not saying anything political, my use of the material just might.

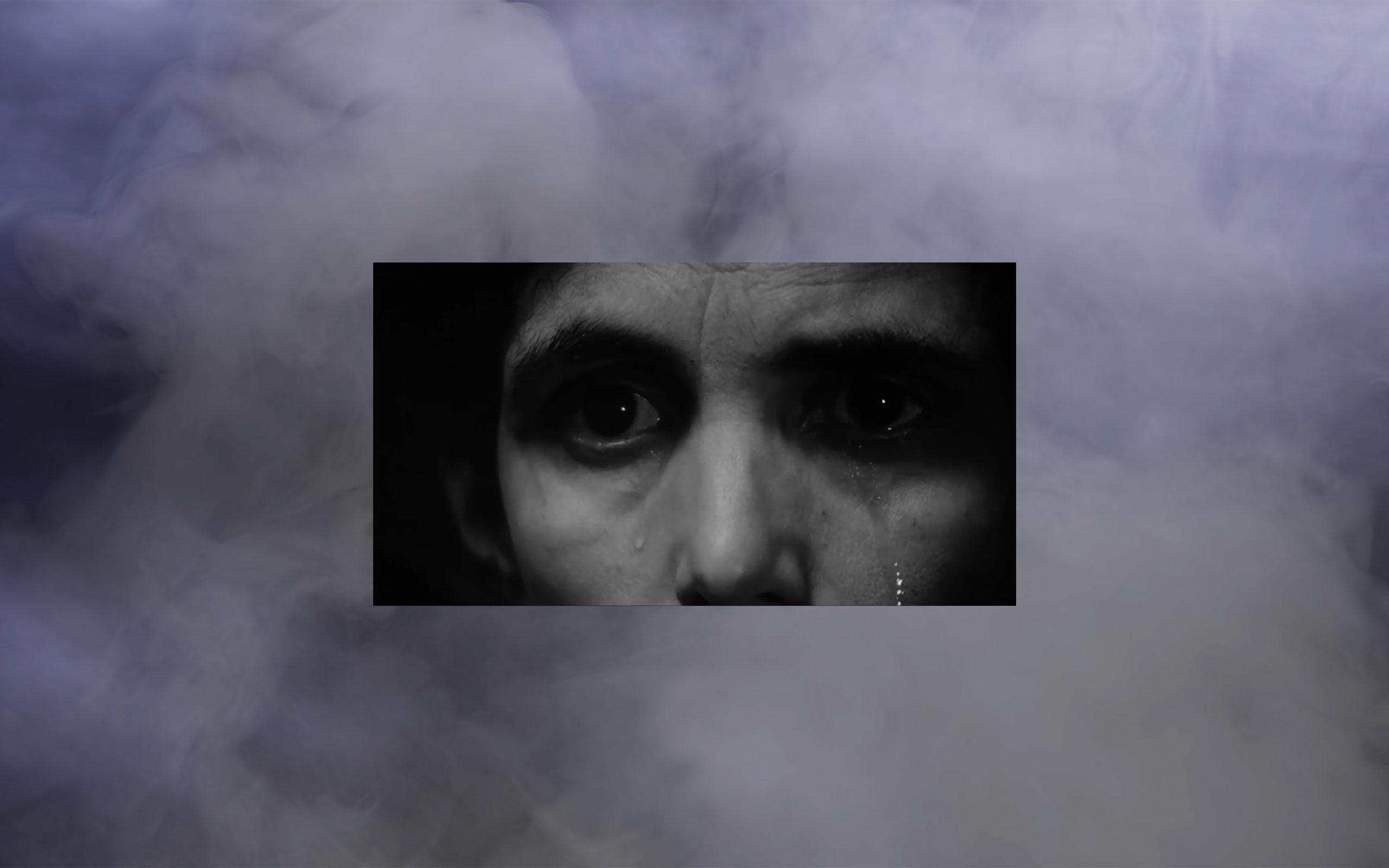

Still, Clarity is the Closest Wound to the Sun, One Channel Video, Color, Black&White, Sound, 2023

Still, Clarity is the Closest Wound to the Sun, One Channel Video, Color, Black&White, Sound, 2023

Talking about expressing political views – do you ever think of going back to Syria?

Yes, I do. But it is obviously not a good time at the moment. Each time I visit, the economic situation really hits me; everything is collapsing. All the art galleries and art spaces decamped in 2011 for Dubai, Paris, etc. There is sadly nothing left in Syria. Of course, you could show work in off-space spaces, but that means no income! And when I think of the way I work by using archives, I don’t think that I could do my research the way I want to.

And probably not say what you want either, or not openly at last. Does the fact that your work is made up of different layers come from this necessity to hide, too?

One can say that. However, I personally don’t appreciate art that can be understood at first sight. A work of art should not reveal itself all at once. I need to be challenged by the work, and I would rather figure out its meaning by myself; it is much more interesting that way. And that is exactly what I want to achieve with my work, too.

Speaking about work – right now you are based in Vienna. What do you think about the working and living conditions here?

Somehow, I seem to have a love/hate relationship with Vienna, because it has been something of a double-edged sword. On the one hand, I really cannot complain because, since I finished my MA at TransArts in 2020, exhibitions, projects, and residencies keep coming along. Additionally, the funding for my current PhD position at the academy of Fine Arts allows me to concentrate on my research and work. On the other hand, there is still an underlying feeling of being an outsider, not helped by an increasing amount of bureaucracy wherever I turn. So, I won’t rule out moving away one day.

What comes next for you, work-wise?

Well, in 2024, the video about the artworks of my grandmother will be shown at Kunstraum Lakeside in a solo exhibition and in a group exhibition at Künstlerhaus Wien. I am also planning my first feature film, which draws from a video I presented at Crone Gallery; it questions the hidden history of the Algerian female freedom fighters who fought the French during the Algerian-French War and their subsequent representation in Gillo Pontecorvo's 1968 film The Battle of Algiers.

Interview: Alexandra Markl

Photos: Maximilian Pramatarov