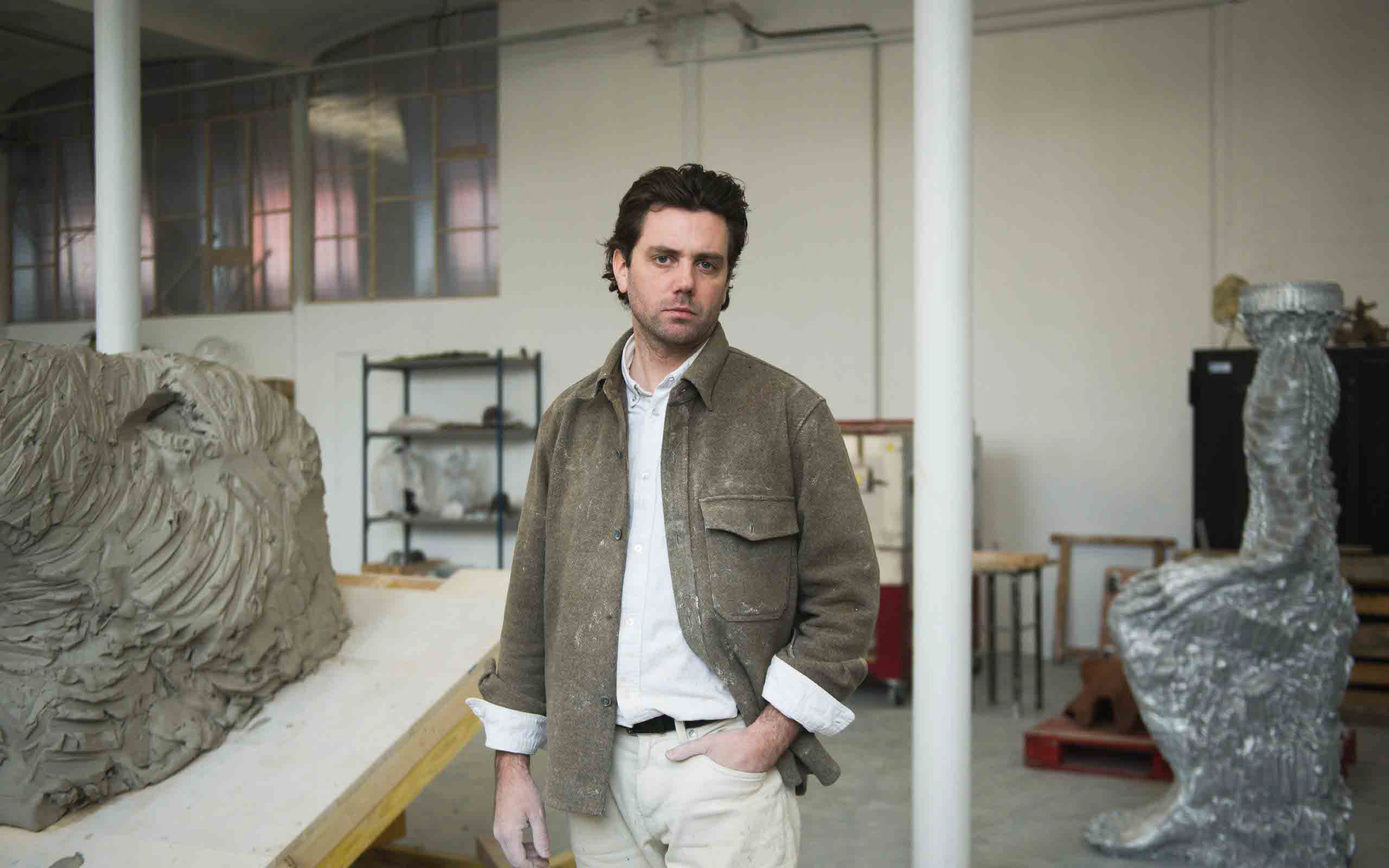

French artist Jean-Marie Appriou uses various materials, such as clay, bronze, and glass, to craft immersive sculptures that evoke mythological and surreal landscapes. Through his process-driven practice, he explores themes of mythology, subconscious realms, and universal narratives. In his sculptures, the artist blends classic influences with contemporary narratives, bridging his respect for ancient artistic traditions with a fascination for science fiction and different states of perception.

Jean-Marie, did you always want to be an artist?

I’ve always wanted to be an artist. Growing up in Brittany, on the west coast of France, I was fascinated by art from a young age. Paul Gauguin, who worked in the region after spending time with Van Gogh, was a huge influence. I grew up near Pont-Aven, and as a child, I’d visit the museum there to see his paintings. Even back then, I knew I wanted to be an artist. I was lucky because my father, who made pottery and was a theatre set designer, encouraged me. He let me experiment in his studio, where I worked with both paint and clay. He also had a kiln, so I was able to make ceramics from an early age, which I still enjoy today.

So, did your parents support your artistic career from the beginning?

Yes, my parents have always supported my artistic development and have accompanied me throughout my career. My mother was a primary school teacher, and my father designed theatre sets. I grew up in a creative world, surrounded by walks, books, museum visits, and costume design.

Where did you study, and what were your first steps as an artist?

I spent a lot of time in my father’s studio, but when I went to school, I also learned the technique of etching, which gave me a new perspective on art, adding a dimension beyond painting and sculpture. Later, I went to the Beaux Arts in Rennes, where I met a teacher who helped me expand beyond my early experiences in Brittany. It’s hard to pinpoint exactly when my journey as an artist began—it always felt like a part of me. While studying, I had the chance to do small exhibitions at school, and I realised there wasn’t a clear starting point. It felt more like a continuous flow, like a river that has always been there.

How did you develop the practice that you are known for now?

After graduating, I moved to Paris and started working as an assistant for artists who were about ten years older than me. It was a huge learning experience and I quickly realised the gap between the more conceptual and intellectual focus of art school - as well as the hands-on reality of running a studio and creating work, especially in sculpture. Since I was really drawn to sculpture, I knew I had to understand the practical side, and working alongside these artists gave me that insight.

What happened next?

After that, I went back to Brittany to stay with my parents. At that stage, I didn’t have a gallery, a studio or the money to support myself, so it made sense to return and set up my own space. I built my own foundry, where I could produce aluminium and cast-iron artworks, experiment with casting, and develop my ideas without relying on a gallery for funding. Then, in 2014, not long after graduating, I was invited to exhibit at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris. That show got a lot of attention, and it was also when Jan Kaps, the gallerist from Cologne, discovered my work and started representing me. That really marked the beginning of the next chapter in my career.

How do you describe your artistic concern in your own words? What matters to you most within your practice?

My practice depends on being in the studio daily—it’s like training for an athlete. Working there feels almost meditative, like a spiritual practice, though not religious. Each sculpture inspires the next, starting with a single element that evolves into variations. Sculpture is collaborative, and the studio’s energy keeps ideas flowing. Often, I only see my work with fresh eyes when I look back at it in catalogues, like rediscovering something new. My process feels like a river, strengthened as new pieces flow in. I’m inspired by filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky, who said that in his films, the work is the master, and he’s the student. I feel the same—each piece teaches me, and I grow through it. In a way, I’m a student of my own work.

Who or what has influenced your approach to sculpture the most?

I learned from my professors at the Beaux-Arts school. They taught me the foundations of sculpture, rooted in antiquity, the Renaissance, and minimalism. Some of my teachers were deeply influenced by minimalism—they had started their careers in the late '60s and '70s—so they passed on that connection to me. That’s why I have a deep love and respect for minimalist artists from the 1970s. There was something almost mystical about their relationship with form. And from there, I realised that I could build on that or even rebuild something new—bring figuration back into the picture. Because in a way, minimalism had already opened the doors.

Beyond minimalism, are there philosophical or literary ideas that shape your artistic thinking?

I often think about this quote from William Blake that I love: "If the doors of perception were cleansed, everything would appear to man as it is, infinite." That’s actually where the band The Doors got their name—from Blake’s words. And this idea of perception, of expanding it, whether through psychedelics or altered states, has always been part of artistic exploration. I also use that quote in my own thinking about stereoscopy. Dreams, for example - when I unconsciously make connections between materials or ideas, it’s like I’m creating collages. A bit like Russian realism, or like Max Ernst, whom I admire so much—how he could take a piece of the ground, do a collage, and suddenly create these unexpected associations. For the brain, it’s like opening doors between different worlds. That’s what Dadaism and Surrealism did—they opened doors for artists.

Would you say that this idea of interconnected worlds also extends to your view of history?

Yes. And today, with advancements in physics, we talk about multiverses instead of a single universe. Maybe dreams, or the unconscious, are indeed portals between different realities. When I think about the history of human creativity, I don’t see it as a straight line from prehistoric man to today. To me, it moves in loops. The art of our ancestors, prehistoric humans, is just as important as Michelangelo and the Renaissance—it’s all connected. We keep coming back to the same questions, the same concepts, the same anxieties. We still don’t have answers about the nature of time. Einstein showed that time is relative, and quantum physics suggests the existence of multiverses, For me, all of this is deeply interconnected.

How does science and science fiction influence your art?

Science fiction, film, and graphic novels have always been huge influences on me. I’ve always been drawn to the work of avant-garde filmmakers like Alejandro Jodorowsky, and writers like Alan Moore—From Hell, V for Vendetta, and Watchmen have definitely shaped how I approach storytelling. Writers like Moore and Lovecraft, along with the explosion of anime, really defined the culture of my generation. I also get a lot of inspiration from classic literature, and characters like Frankenstein, who has always fascinated me. And cinema—especially with all its 3D innovations—has completely changed the way we experience the world. Even though I work with traditional techniques, sci-fi film imagery still grabs me every time.

With which materiality do you work most?

In my studio, I start with clay and mould it myself. Then, Clément and Raphaël make the mould, which goes to the foundry for a wax model. Once it's ready, it's encased in plaster, and metal, like bronze or aluminium, is poured in—using a traditional technique, similar to Rodin's. For my 2023 exhibition at Eva Presenhuber in Vienna, I was inspired by Rainer Maria Rilke. Rilke was a poet and was Rodin’s “secretary”. He even wrote about the connection between sculpture and writing, and when I read Rilke, especially after his time with Rodin, it feels like a sculptor’s voice. For both of them, clay is fundamental, and for me, it’s where everything starts.

How does working with clay influence the way you think about the temporal nature of your work?

I draw inspiration from the studio, the world, and even the cosmos. When I start sculpting, there’s an idea, but at first, the clay is just a block, a geometric pile. Then, I shape it into a face or body…Timing is also crucial—there’s light, there’s heat. In summer, for example, I must work quickly because the sun dries out the clay fast, so I’m constantly adding water. In a way, I’m working with earth, water, and my hands—it feels almost timeless, like a process beyond any specific era. We talk about the primordial soup, about temperature, water, and enzymes—conditions that led to the first cells, the first life. But maybe it all starts with clay. It feels protective, and when I hold it, I always think of it as shaping life itself, moulding the future.

How do you build narratives between your characters across different works?

I often use the metaphor of theatre. What I love about it, is the variety of characters, and I’ve always been a big fan of Shakespeare. I’ve created many sculptures inspired by Hamlet, with Ophelia, and Macbeth. When I sculpt a body, I give it a role, like putting it in a costume—part of a narrative performance. This idea also connects to how I work in the studio—it’s like playing a role. It takes me back to my childhood when I loved dressing up. One day I told my mom and dad I wanted to be a Viking, and the next day, I wanted to be a Native American or a cowboy. As children, we have this openness, this desire to be anything but ourselves, as a form of escape, to play at being something else. I see sculpture in the same way.

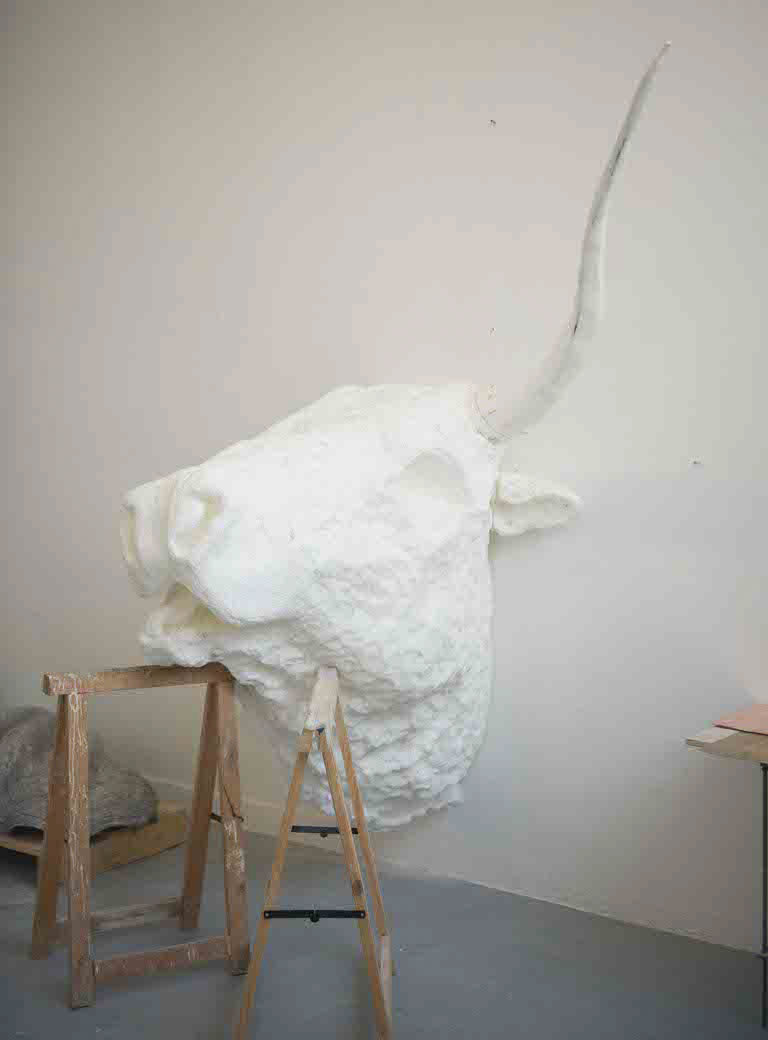

Your works are often monumental yet evoke a sense of fragility. How do you approach the relationship between scale and emotion in your sculptures?

I sculpt at scale, even for works that reach 6 meters in height. What I enjoy about modelling clay is that it’s a hands-on process, and it often doesn’t replicate what a photo might show. The human hand scale is key—whether the sculpture is 5, 6, or 7 meters tall, the hand’s scale brings an emotional connection for the viewer. It allows them to relate, to recognise something familiar. For example, with The Horses sculpture in New York, I intentionally left the fingerprints visible on the mouth and nose, creating something almost sensual. It’s about evoking emotion by bringing the viewer back to their own scale.

You've mentioned New York, your installation at Central Park. How does the location of an exhibition influence your approach to a work?

The Central Park experience was meaningful because it was the first time I saw my work interact with the public— not just art lovers, but everyday people. I found it fascinating how some would ignore the sculptures, while others would engage, even climbing on them. It connected my work to a wider world, beyond the art world, allowing people to experience it. With millions of visitors every year, it offered a unique view of how the public interacts with and even takes ownership of the art.

What are the challenges and rewards of working at a monumental scale?

The real challenge is the work in the studio. For example, in the studio, the pieces might touch the ceiling and fill up the space, but when you take them into reality, like in Central Park, New York is massive—there are buildings, taxis, cars, and people. The challenge is bridging the calm, white cube of the studio with the bustling reality outside. The contrast between the studio and the scale of the city is striking—an ordinary tree in the city can be 10 meters tall, so the sculpture always feels different in that space. It’s a projection of the mind.

Is your art also sometimes misunderstood?

I create work that’s figurative and narrative, so people can at least see and understand it. But the challenge is always pushing myself to make something more complex and personal. Sometimes, the difficulty lies in the gap between words and the artwork itself. There’s a difference between how we explain something and what we actually see.

You often collaborate with foundries and craftspersons. How important are these partnerships in your practice?

Being a sculptor means there’s the studio work where I create the sculptures, the moulding process, and then the foundry or glassblower who bring the final piece to life. When my sculptures are made of metal, I work with a foundry, which is why I started my own in Brittany—to understand the process. Once I did, I could collaborate with others. It's similar to making a graphic novel—Alan Moore, for example, was the writer of Watchmen, V for Vendetta, and From Hell, working with different illustrators. Finding the right foundry is like that—they need to understand my approach and vision.

How do you see your work within the broader context of contemporary sculpture?

It’s complicated because you’re focused on your work, but you don’t have the full feedback yet. You get immediate reactions but not a long-term sense of how people will truly perceive things. For example, when I started using foundry work in my practice, it wasn’t anything special. Young artists weren’t working with bronze or aluminium—it wasn’t “in vogue”. But over time, things changed, and now many young artists are doing their own foundry work. It’s something you learn with experience. Staying connected with artists of your generation is important to understand the concerns of the moment, but it’s hard to have perspective. Time is what reveals the significance of things.

What are your next projects?

I have a solo show coming up at the MOCO in June 2025, which I am very much looking forward to. Additionally, I am also in conversations with two other institutions, which is exciting as well!

Interview: Livia Klein

Photos: Elise Toïdé