The scene for contemporary art in Europe’s North is expanding and developing new dynamics as international collectors are watching the scene. With Nordic Notes we cast the eye on the Nordic art and cultural scene, portraying its most important actors.

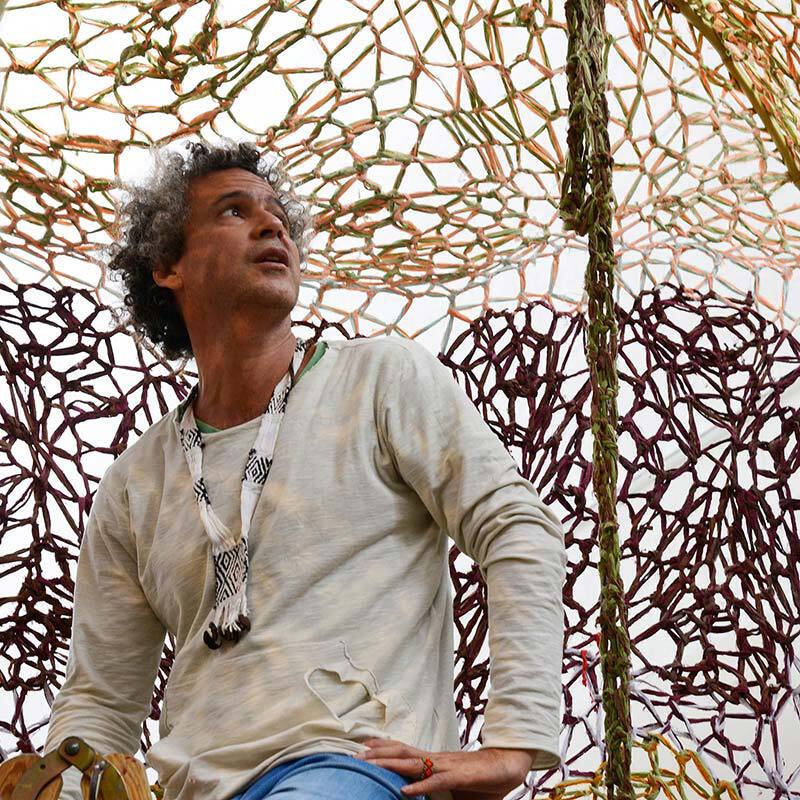

The Danish painter and sculptor Johannes Holt Iversen has bases in Copenhagen and Amsterdam. Before training at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam, he worked in the music industry. He focuses on exploring the tension between artificial and organic material and life forms and works with both traditional art forms and cutting-edge technology including AI, to imbue his viewers with an existential awareness of the hyper-slick representation of reality that surrounds them. We spoke with Iversen about the burden of Scandinavia’s aesthetic heritage, collaborating with the director of fermentation at Copenhagen’s renowned Noma restaurant, his teenage admiration of Justin Timberlake, and why, for him, art and science are two sides of the same coin.

Johannes, how did you first become interested in art? Who were some of the first artists that inspired you?

In my early teens, I visited the ARoS Aarhus Art Museum. There, I saw JORN International, an exhibition of work by the Danish abstract artist Asger Jorn. The way the show presented the artist’s mythological ideas—working across the globe at the new frontier of art—really captivated me. Before that, as a child, I was interested in the early Impressionists, especially Monet; they had a very strong impact on me. I copied their style and tried to mimic their way of seeing; I was especially attracted to the colours the Impressionists chose to use. Their works have this specific lightness. When they painted darkness, they didn’t just use black, they drew from a vivid scheme of violets, browns, and greens.

You worked in the music industry before becoming a visual artist. How did you come to be in the world of sound?

I come from a family of musicians. From a very early age, everyone was compelled to perform. To have an identity, you had to perform, or at least be able to sing in a choir. For me, it was important to be able to create my musical vision, so I started to write my own songs to process what I saw and learned in the world. When I was younger, I also tried to impersonate what I thought was cool. In my early teens, this would mean someone like Justin Timberlake. After writing songs for a while, I was noticed, and ended up in the music industry.

What music do you like now? Are you still a Justin Timberlake fan?

I listen to weird underground music, ‘Massive Attack’ and ‘Radiohead’. I also listen to heavy rock and pop—my personal playlist features everyone from Harry Styles to Mozart! I have no filters basically. When you have filters, you get blocked. If you think that you should only engage with ‘high art’, you tend to become disconnected from what’s actually going on in the world.

Why did you decide to move away from music and towards the visual arts?

I started to realise that the music scene, the American music scene in particular, is a very harsh environment. I had some difficult experiences with representation in New York and LA. I figured out that the music business wasn’t really a good place for me to work. I started to think about the elements of creation that I really liked. As a musician, I always preferred being in the studio than being on stage. I loved being with all the audio geeks and sound engineers who would turn knobs and generate new, weird sounds. From that, I realised that music studios and art studios bear a resemblance to each other. I was already painting; art and music had always gone hand in hand for me anyway. In 2014, I very clearly decided to focus on visual art. I wasn’t quite sure how I would do this because I didn't have any access to that world. It seemed like this closed, esoteric sphere. I studied marketing and digital media at university, which has now become a huge part of my practice. Through that, I encountered the right people, and was introduced to an artist who taught me everything I needed to know to get into an art academy.

That artist was the Danish painter and sculptor Erik Rytter. He was a former assistant to artist and furniture designer Poul Gernes, who also founded the alternative art school Eks-Skolen. What inspired you about his work and practice? Why did you want to learn from him?

Erik was trained at the Academy in Prague during the Soviet era in the 1980s. The way he was taught reflected the way that I had learnt music with my family. He knew that you must be extremely disciplined and learn the fundamentals before you are able to attempt anything more advanced. I told him that I really wanted to go to the Royal Academy of Arts in Copenhagen, but he thought my style and interests weren’t in tune with the scene in Scandinavia at the time. He suggested that I should move out of the region, and recommended that I apply to the Gerrit Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam and the Beaux-Arts de Paris. I ended up entering the former in 2016.

Denmark has a strong art and design heritage. Though you weren’t in tune with the mood of the art scene when you were training, do you think Danish aesthetics have influenced your work at all? Even if only as something from which to move away.

Arriving in Amsterdam was a relief. At the time, I was a weird painter completely obsessed with the COBRA movement. That did not fit well in the Copenhagen art scene. In Amsterdam, people embraced it more. Being there made it easier for me to explore new things. If I’d never left Denmark, I wouldn’t know what was going on in the rest of the world. I would be overly influenced by this very severe Scandinavian school of art, design, and lifestyle, which I think ought to push its boundaries a bit more. When certain styles become very popular, they tend to consolidate themselves. I think it’s important to reflect on why something is successful. What happens when you become confronted with the same set of grey, dark colours in different tones all the time? Does it give you the right to say that you have the ultimate aesthetic ideal in the world? I’ve heard artists say that before, but I think it’s wrong to put yourself on that kind of pedestal. It was good to get away from home and find out what the perception of Scandinavia is from the outside.

It’s interesting that where you’re born—something you have no control over—has such a strong influence on how you perceive and navigate the world.

If I ever got lonely in Amsterdam, I used to go to IKEA to eat meatballs. That was my Scandinavian fix. It’s a cliche, but it also made me think about how when I create art—whether that’s painting, sculpting, or drawing—eventually I will always face the Scandinavian in me again. I think what a modern Academy does is confront you with the innate culture you bring to the table, so that you create work from a place of awareness of that culture.

How did you transition from training to entering the professional art industry?

I had to fund all my tuition fees myself. I also had a lot of student debt from my previous studies, so I couldn’t just take another loan, but it was also difficult for me to have a job and be a full-time student. Therefore, I started selling my works while I was studying, and worked as an artist secretly. It wasn’t something I wanted to advertise to my professors. When I finished art school, it meant that I already had gallery representation, and that I’d already had multiple smaller shows. Some artists talk about the void between art school and working professionally as an artist, but I was very lucky that I had a soft landing in a way. That said, I graduated just as the global pandemic was beginning. I had to figure out how I could maintain my art practice and realise my vision of having two studios: one in Amsterdam and one in Copenhagen.

Why do you require two studios, do you use them for different purposes?

My Danish studio is where I produce large-scale works. I’m there most of the time. My Amsterdam studio is more like a small-scale laboratory. It’s where I play around with odd things that I’m not certain about. I go there for a few days at a time to work intensively. Being in Amsterdam reminds me to keep experimenting and push my own boundaries. It can be a bit hard to remember that as a professional artist when there is so much pressure to keep producing. My Amsterdam studio is my ashram, so to say, where I retreat and meditate.

How would you describe your artistic practice and thematic interests now that you’ve been out of training for three years?

Most of my works now examine the duality between artificial and organic life. The pandemic, and recent developments in AI, have also really influenced my practice. I’m interested in imbuing people with an existential awareness, and asking: what is artificial? What is organic? What is real? I want to tap into these curious questions and confront them with the reality of today, i.e., the materials and hyper-commercial slickness that surrounds us.

Your interest in the tension between organic and artificial is evident in how you produce your works: you work with traditional media such as painting, as well as modern technologies such as AI.

This approach is very clear in my upcoming exhibition, Skinwalker IO, which will open at Annika Nuttall Gallery on 26 May 2023. I’ve been working on the project since the end of 2021, when I started looking into prompt-based interfaces, and how I could feed computers with commands to see how they would respond. I quickly realised that a lot of AI-based research had already been done that would enable me to work with a computer, feed it with information, and receive figurative, artistic responses in return. The AI responses were very literal at first. If I fed the computer the prompt ‘polar bear’, for example, it would show me a polar bear. I wanted to explore how I could trick the AI into producing more subconscious responses. To do this, I created haikulike prompts, which made the computer develop what I call ‘subconscious absurdities’. After some trial and error, I honed my approach, and started to make a series of paintings based on what the AI produced. These will be shown as part of the exhibition. I will show some of the purely digital studies too, but I think the physical ones will be the most interesting. They are a combination of mine and the AI’s work and demonstrate how the physical world can be influenced by modern day technology. Some studies are also going to be made available as NFTs.

You collaborate with both humans and machines. In December 2021-January 2022, you worked with Jason White, the Director of Fermentation at the highly acclaimed restaurant Noma, to create a work that is now displayed in their Fermentation Lab. How did this come about?

I was corresponding with Jason on social media for quite some time. He was very keen to find out more about my artistic processes. At the time, I was researching organic and biological visuals, which crossed over with his interest in bioscience and the development of edible elements for Noma’s menu. He invited me to visit the restaurant’s fermentation lab, gave me a tour, and took me foraging. Through conversations, we realised that the way that they process mould at Noma—they can pause any biological process so that it stays in its most beautiful or colourful state—crossed over well with my interest in the duality between organic and synthetic materials and processes, and we decided to work on a project together. The whole collaboration arose out of a joint interest in science and art, and how these two platforms can meet.

Many see science and art as opposites…

Both disciplines push each other in certain ways. When they work together, interesting things can happen, and you can have conversations that you wouldn’t necessarily have in a purely creative or purely scientific environment. For me, art and science are two sides of the same coin, with philosophy sandwiched somewhere in the middle.

What are your ambitions and goals for the future?

The project with Noma is indicative of how I want to work moving forward, because it was so organic and came out of nowhere. Most of my ambitions of achieving particular accolades died with my music. I had so many dreams about going to New York, securing full time songwriter contracts, or signing with a big label. When I transitioned into visual art, I told myself I had to put ambition to one side and just focus on the process. That is my new ambition: to focus on creation. If you have really set specific goals, then you reduce the chance of doing something amazing, weird, and unexpected, because you’re busy chasing other things.

Exhibition Viewer Berlin, 3028 x 2398 pixels, 2022, Stella Allery, G-allery, Berlin 2022, Photographer: Stella-Marie Allery

Location: The Royal Danish Embassy Netherlands, 3456 x 4608 pixels, Hague, the Netherlands, Photographer: Chiel van Beurs, the Minitstry of Foreign Affairs Netherlands

Interview: Emily May

Photos: Rebecca Krasnik