John Akomfrah is an artist, filmmaker and screenwriter, who deals with the structure of memory, the diasporic experiences of migrants and the historical, social and political roots of colonialism and post-colonialism. As a migrant himself, John Akomfrah is very careful and considerate in the way he tells and treats the experience of migration. For this reason his art seems not only touching in a unique way, but is also highly political.

John, among other topics, your work deals a lot with the investigation of colonialism, post-colonialism, and migration. Why was it so important for you to work along these topics and why is it still important for you to address and work with these topics today?

Choosing my work to deal with these issues came with certain responsibilities. I came from a generation, which was the first to be born and grow up in postwar England. So on one hand, my responsibility was to explain myself to myself and on the other hand I wanted to explain myself to the host society. I grew up in the 1960s and 1970s, so there were no models or prototypes for “what we were”. We were the first off the factory floor, so I became interested both in the colonial, as well as in the post-colonial, as part of that attempt and to understand the structural formations in British society. But I am no societal engineer, I do what most artists do, which is to attempt to understand themselves and the cultures that somehow formed them.

Memory and everything associated with it, plays an important role in your art as well.

I think that everybody and all formed diasporas have brought memory. But what does it mean to be a diasporic entity? You inhabit spaces in which your existence is not marked, so the question of memory is a critical one of the means, by which your identity is secured. And that’s why memory is so important to me in my work.

John Akomfrah, Mnemosyne, 2010 Single channel HD colour video

© Smoking Dogs Films; Courtesy Smoking Dogs Films and Lisson Gallery

John Akomfrah, Mnemosyne, 2010 Single channel HD colour video

© Smoking Dogs Films; Courtesy Smoking Dogs Films and Lisson Gallery

John Akomfrah, Mnemosyne, 2010 Single channel HD colour video

© Smoking Dogs Films; Courtesy Smoking Dogs Films and Lisson Gallery

John Akomfrah, Mnemosyne, 2010 Single channel HD colour video

© Smoking Dogs Films; Courtesy Smoking Dogs Films and Lisson Gallery

We are regarding major political developments in the western world today. In your opinion, how does a concept like BREXIT affect migration policies in Britain?

I’d like to describe BREXIT as an “elephant in the room”. People who were campaigning for BREXIT claimed, that it was all about taking the country back and I didn’t know what that actually meant. But I knew, that in reality, it was about making a distinction about two things; body and goods. In the end, it was about the goods that we want, and the people that we don’t want. BREXIT doesn’t want people, but it does want goods. As a foreign body it was very difficult for me to deal with this conversation, because I knew it was about me. People have spent their entire lives in a culture and made contributions that they somehow assumed were positive. But it wasn’t enough for the majority of British society. Foreign bodies were not a good idea. BREXIT would rather swap you for beans and cheese and to figure this out really hurt me. Migration politics will be affected and the questions are: What price are people willing to pay to have control over their borders and are people willing to see great Britain shrink to little Britain. These are the real questions.

Migration is a very delicate topic to deal with in art. How are you working with this phenomenon, since it is a diverse experience for migrants, depending on their gender, country of origin or age?

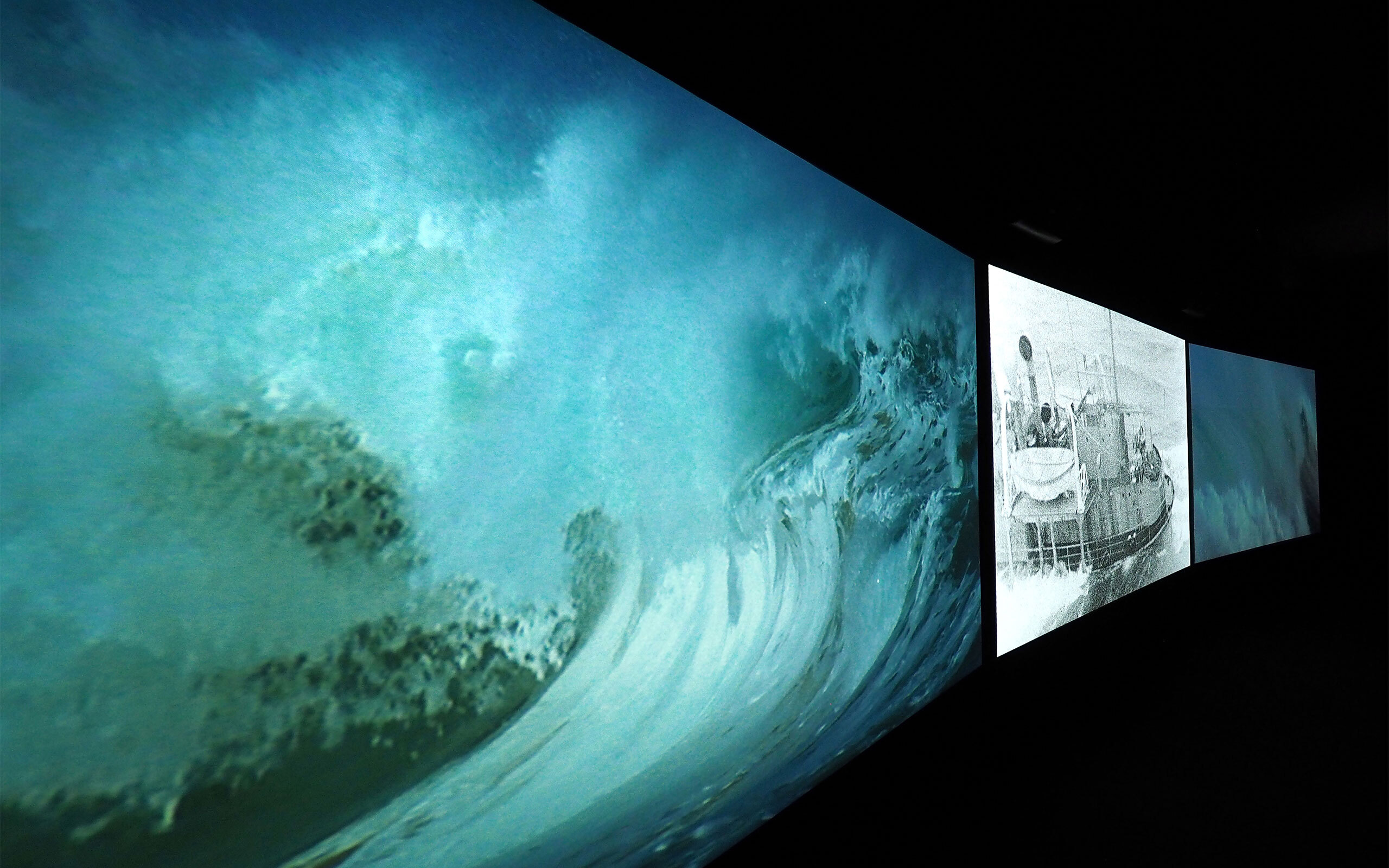

I was four years old, when I experienced migration, and it happened through the lens of the feminine. My mother was the one, who brought us from abroad and it was through my mother’s protection, care and being, that we experienced migration. We didn’t have a father, because he had died. Migration would have been differently experienced by me, if I had crossed borders myself without my siblings, or with my father. A black woman from west Africa with four children marked those children in a very particular way. For my work Vertigo Sea, from 2015, we have been interviewing migrants, some in very precarious circumstances, and talked carefully about their experience.

Vertigo Sea is a highly emotional – yet very aesthetical work. What would you like the viewer to experience while watching this particular piece?

I like to construct portraits of things. Those things are both eligible and happy at the same time. I don’t want people to feel sad, but I am not a salesperson for happiness either. I need the mix, because this mix is human, normal, and necessary. We live in an age, where you can experience things, that can make you feel sad, but also happy, because you were able to experience this sadness. We can learn a lot about ourselves by being confronted with difficult issues. It is important to say, that I don’t want to teach people anything. What I want to do is to start a conversation. You need to know, that the ships you see in this world are the ones that captured wealth but they also captured humans. Maybe my art can work as a reminder.

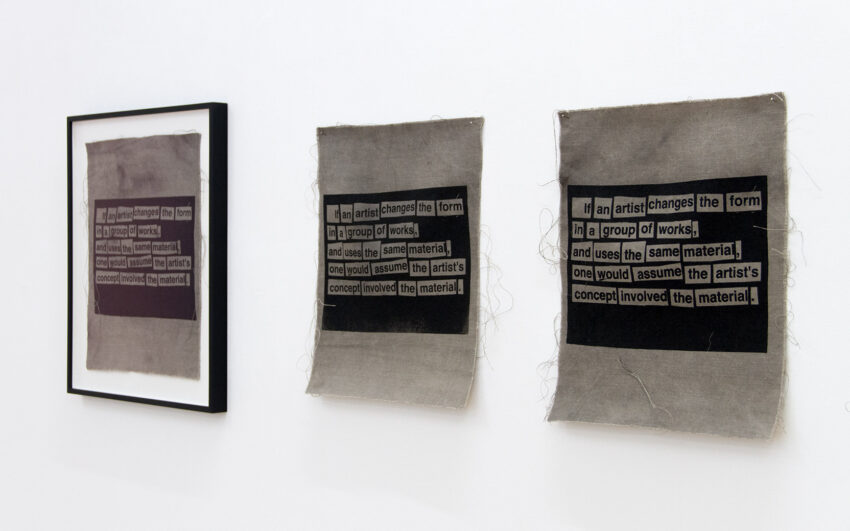

John Akomfrah, Peripeteia, 2012 Single channel HD colour video

© Smoking Dogs Films; Courtesy Smoking Dogs Films and Lisson Gallery

John Akomfrah, Peripeteia, 2012 Single channel HD colour video

© Smoking Dogs Films; Courtesy Smoking Dogs Films and Lisson Gallery

John Akomfrah, Peripeteia, 2012 Single channel HD colour video

© Smoking Dogs Films; Courtesy Smoking Dogs Films and Lisson Gallery

John Akomfrah, Peripeteia, 2012 Single channel HD colour video

© Smoking Dogs Films; Courtesy Smoking Dogs Films and Lisson Gallery

John Akomfrah, Peripeteia, 2012 Single channel HD colour video

© Smoking Dogs Films; Courtesy Smoking Dogs Films and Lisson Gallery

Famous writers and theoretical thinkers, such as Stuart Hall and Virginia Woolf are quoted in your works. Why are these writings and theories important to you?

Stuart Hall was a mentor for me, who became a friend later. In the 1980s I was part of a collective called ”Black Audio Film Collective“. Our first film dealt with the area of Birmingham, in which Stuart Hall used to teach. We invited him to see our movie and started to become close as we were discussing the work. When I grew up in the 1970s, writers and great thinkers, like Virginia Woolf, Friedrich Nietzsche, and Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak became very important to me, because I was living in a time were theoretical experiments, critical theory, and feminist writings were on the rise and possible. I am a child of that movement. I do still read the books by these writers, although my interests in their writings have changed. For example I have been fascinated by Virginia Woolf’s novel Orlando, because I thought it was such a great story about transformation. Today I prefer to read her book To the Lighthouse, because of her description of time and her illustration on light and how it works on the characters.

Is there a particular process that you follow when developing your video work?

All the projects have the same structure of production. There is a period of research, then comes a period of editing, the montage of already existing material or found footage and the construction of the form that they would take. Sometimes there follows a period of gathering new material or even shooting needed material we couldn’t find. Research is definitely the longest and the first approach of my work. But I have to say, that every project is different. So I ask each project what it needs and wants, and once I know the answer everything else happens very quickly.

Is there any historical moment, that you experienced recently, that told you more of a society that you knew before?

I think it was four years ago, when Theresa May came up with the expression “hostile environment”. The whole hostile environment policy approach was designed to make staying in Britain as difficult as possible for people without leave to remain, in the hope that they would leave voluntary. In a way hostile environment is the motif of my work and I found it so strange that my motif was explained by a right-wing person. It definitely sums up everything that is going wrong with this world for me.

John Akomfrah, Vertigo Sea, 2015 Three channel HD colour video installation

© Smoking Dogs Films; Courtesy Smoking Dogs Films and Lisson Gallery

John Akomfrah, Vertigo Sea, 2015 Three channel HD colour video installation

© Smoking Dogs Films; Courtesy Smoking Dogs Films and Lisson Gallery

John Akomfrah, Vertigo Sea, 2015 Three channel HD colour video installation

© Smoking Dogs Films; Courtesy Smoking Dogs Films and Lisson Gallery

John Akomfrah, Vertigo Sea, 2015 Three channel HD colour video installation

© Smoking Dogs Films; Courtesy Smoking Dogs Films and Lisson Gallery

Interview: Alexandra-Maria Toth

Photos: Alex Schneideman