The work of the artist Jonas Feferle initially appears as minimal and cool, although on closer inspection irregular and exciting material interventions become apparent in order to interrupt the “sleeker” moments of the works. Impact metals are lined up in plates to facilitate sorting and to change spatial conditions. What is important here is the physical experience of the art itself, the preoccupation with the existing and with the added, as well as a clear examination of the categories space, material, and form. Proximity and distance also play an equally important role in the experience of his art, which often manifests itself in room-filling installations.

Could you tell us when and how your interest in art developed?

Art has always been a part of my life, so it is difficult for me to pinpoint a precise moment in time here. However, I can say that I developed an explicit interest in the work of Picasso, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Jackson Pollock in my early youth, around the age of thirteen. Different positions in painting and their opposing movements also fascinated me at the time.

Before you started to study art, you were involved in the humanities.

That’s right. I first began to study philosophy in Vienna. This enabled me to deal with the basic questions of life. That was in my early twenties. Philosophy was very enriching to me while I was growing up. However, I soon recognized that scientific work did not suit me. In addition, I began to experience a certain emptiness that I knew only art could fill, as pathetic as that may sound. That is why the study of art and a focus on photography ensued. I would describe this whole process as a kind of collocation of intuitive action.

The study of art and philosophy overlapped in time. Do philosophical questions find their way into your art?

Yes and no. Of course there are still fundamental questions that occupy me and for which I like to fall back on philosophy. With regard to my work, I would say that philosophical theories on space have been incorporated into my art. However, questions about space and its properties can also be assigned to art historical theories. The connection is, and was, therefore already there, although I would like to emphasize that I have no interest in translating philosophical questions into art.

Material, space, and form are the categories in which you move artistically. Can you describe how you treat these categories?

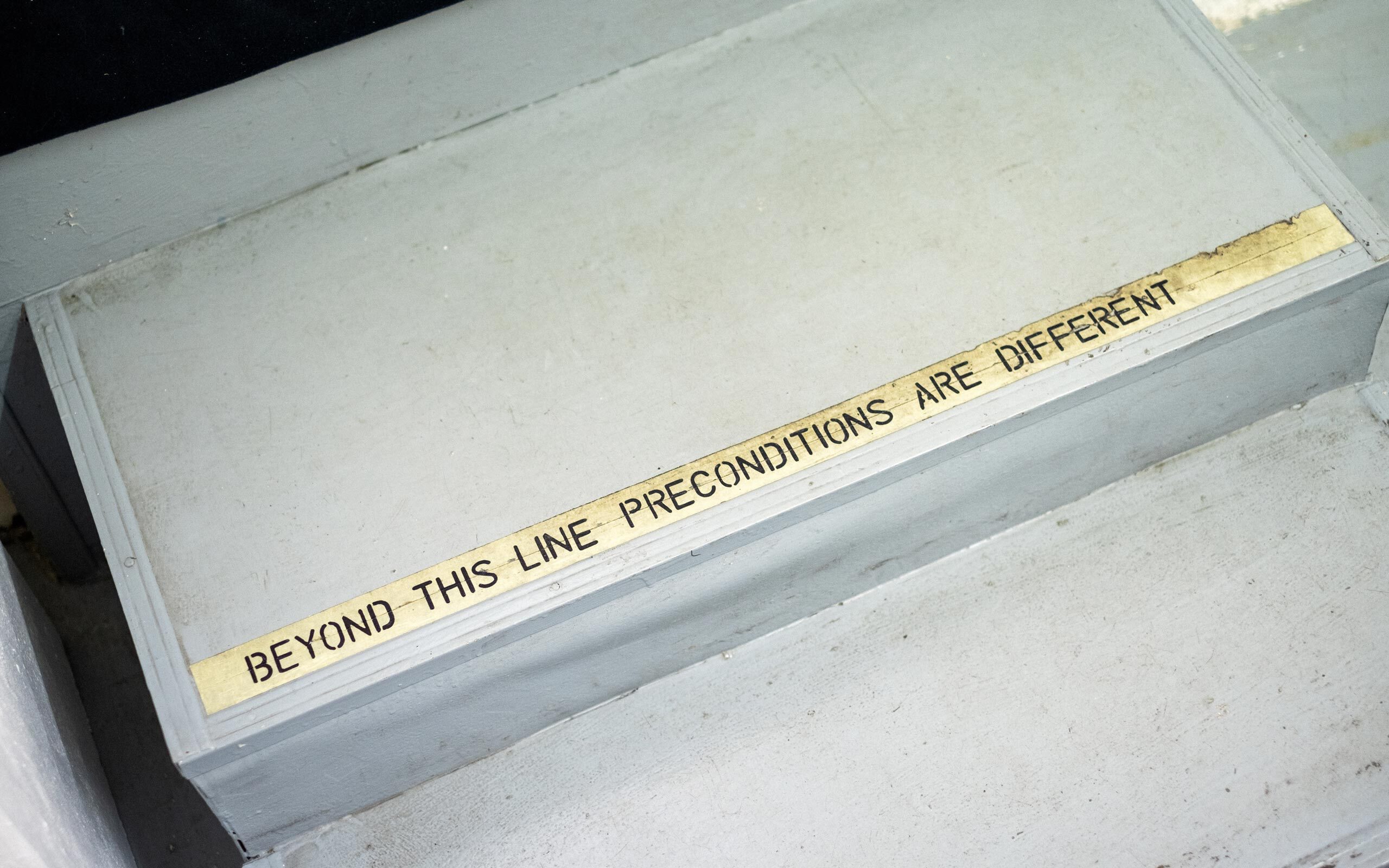

I understand space, material, and form as a kind of precondition that underlies all works and undermines them in the process of transformation. The space can be the exhibition space, but also the material as a surface, which is treated by me. The material is mainly plates and impact metals and the basic preconditions of resources to which I have access. Form is influenced by space, material, and my personal experiences and actions. The decisions I have made and continue to make in life, what influences and occupies me, are decisive for these actions and thus influence the form of the works. The moment of decision is especially interesting for me and affects all of us, because in the end we always have to make decisions in life.

How did it come to the decision to select impact metals as working material?

During my studies I decided to use the image carriers of photography, i.e., Dibond and aluminum plates, as working materials. I didn't make any progress in image production and in frustration tore a photograph from its image carrier. I did this as a gesture for myself, to expose the “behind”. With this gesture and the exposure of the “behind”, i.e. the plate, a new examination of material, form, and space opened up. So I began to work on space-consuming installations, which followed a clear attitude, based on minimal tradition. Later, breaks followed and I began to scratch, grind, and work more intensively on the material. By chance, I came across impact metals and their fragile material properties opened up completely new possibilities with regard to the surface. I also found it very attractive to cover the metallic plates with metal again, to let them become a “Dainter” again. From then on, the working process also became more central, as the technology brings with it other requirements. The laying of the individual wafer-thin sheets as a repetition of the seemingly always same action captivated me.

Is the movement of Minimal Art an important reference in your work?

Minimal and Post-Minimal Art as well as European positions with similar themes fascinated me from a very early stage. I remember a moment in Darmstadt. I was nineteen years old and saw the work Raum 19 by Imi Knoebel in Hessisches Landesmuseum. Even though I couldn't do much with what I had seen at the time, I was still incredibly fascinated. These references are still important for me and my work. In between I have the feeling that I have already exhausted these fields, but in the details there are always unexplored and unknown aspects that require repeated occupation.

Space is a multifaceted concept and often a room must fulfill a certain function. How do you deal with this predisposition when you devote yourself to space?

Exhibition spaces are set in an apparently neutral way, yet still carry challenges within them. Different dimensions, the lighting, the floor, or even the height of the space play an important role. Just like the dimensions and materials of a panel. It is all about what is present and what is added. The space is what exists and the work or works are what is added, both conceal or rearrange spatial elements. Through these transformations, other spaces are created and also a different spatial experience in the viewing. For me, the relationships of space, material, and form only become apparent in the physical experience, when one becomes part of the space oneself, so to speak. Besides classical exhibition spaces, I always find it exciting to work with industrial spaces. The seemingly neutral setting is not given here from the outset, and their respective disruptive elements are a good contrast to the “white cube”.

Your works convey a cool atmosphere. Is this effect intended?

I don’t think in atmospheric categories. Of course these metallic surfaces radiate a sense of coolness, a hermeticism in themselves. At the same time, however, there is also a reflecting effect, which is particularly important to me, because it makes the viewer part of the work. Differently, depending on the setting, the room is also reflected in it. A further ambivalence results from closeness and distance. The further away one is from the work, the more homogeneous and cooler it appears, while from close up an organic moment is revealed, in which breaks become apparent and the fragility of the work becomes visible.

So your work needs the physical experience. For some time now, and currently more than ever, however, exhibitions have been presented online. What is your opinion on this?

We have just experienced a moment of caesura. The physical experience on which our entire art system is built is currently being shaken. I believe that art must be physically experienceable. It is not for nothing that a circus like this is being organized to decentralize art, to make it accessible worldwide. Digital space cannot afford this physical encounter with art, even if we are increasingly moving towards this space. The sensual sensation must be given. Whereby, of course, there are works that take themselves out of here and successfully communicate themselves in digital space.

Do you consume art online?

The flood of images we are confronted with today has been scaled to standardized sizes. I find this approach overtaxing and I also find this kind of art consumption tiring. I also need a degree of emptiness in order to work. For this reason I try to keep my consumption as minimal as possible.

Are there sometimes doubts in the work process and if so, how do you resolve them?

Doubt is a constant companion. Some days a fundamental doubt arises. One wonders whether art should be produced at all, because everything was apparently already there – so what is there to add to what is already there? What is still legitimate? And do we not already live in abundance? The “doing” in this ambivalent relationship occupies me very much. On other days, specific doubts about the work arise, which lead to breaks. I see these ruptures as moments of questioning my practice. But this specific doubt has become quite relative over the years. In the meantime I see these breaks as important moments through which my work experiences extensions. Doubt is therefore necessary.

What preparatory work do you need to do to start your work?

Every intervention in the material is a unique act. I do not sketch anything on the plates themselves, but work directly. I write about my work and listen to a lot of music, maybe these actions can be considered preliminary stages, because they have an influence on my work. For example, already on the way to the studio I think about which album I want to listen to at work. This then runs the whole day in a continuous loop. Currently I’m also working on my own “sounds” with a synthesizer, which I then let run during work. I try to find out how this reduction and repetition of sound influences my approach. I have no interest in adding my writing or sounds as independent elements to my work, but I think that these activities might eventually be reflected in the overall picture of my work.

Your studio seems very tidy. Do you need this order to work?

Yes. Order is essential for me. Everything here has its place, because I can’t stand having to look for anything. You probably see this order in my work as well. It's a continuous arranging, a sorting of surface and form, if you will.

If you hadn't become an artist, what profession would you be in?

Which brings me back to the doubt. There were always moments when all sorts of professions buzzed around in my head as alternatives. But in the end, the emptiness can only be filled by art.

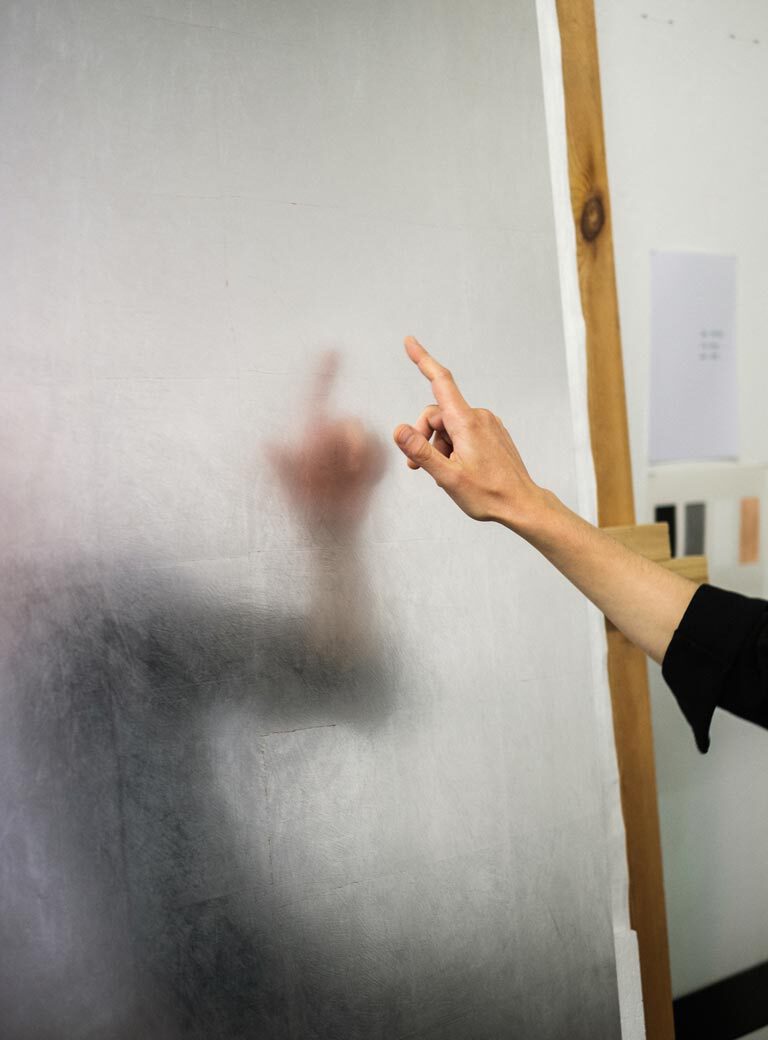

Exhibition view, Silent Matters, Gallery Raum mit Licht, Vienna 2019

Courtesy of the artist and gallery Raum mit Licht, Vienna

Exhibition view, Silent Matters, Gallery Raum mit Licht, Vienna 2019

Courtesy of the artist and gallery Raum mit Licht, Vienna

Exhibition view, A piece of space, material and form., Gallery Raum mit Licht, Vienna 2016

Courtesy of the artist and gallery Raum mit Licht, Vienna

untitled, 2018, aluminum plates, mixtion, impact aluminum, impact copper, varnish

Courtesy of the artist and gallery Raum mit Licht, Vienna

Interview: Alexandra-Maria Toth

Photos: Maximilian Pramatarov