The scene for contemporary art in Europe’s North is expanding and developing new dynamics as international collectors are watching the scene. With Nordic Notes we regularly cast the eye on the Nordic art and cultural scene, portraying its important actors.

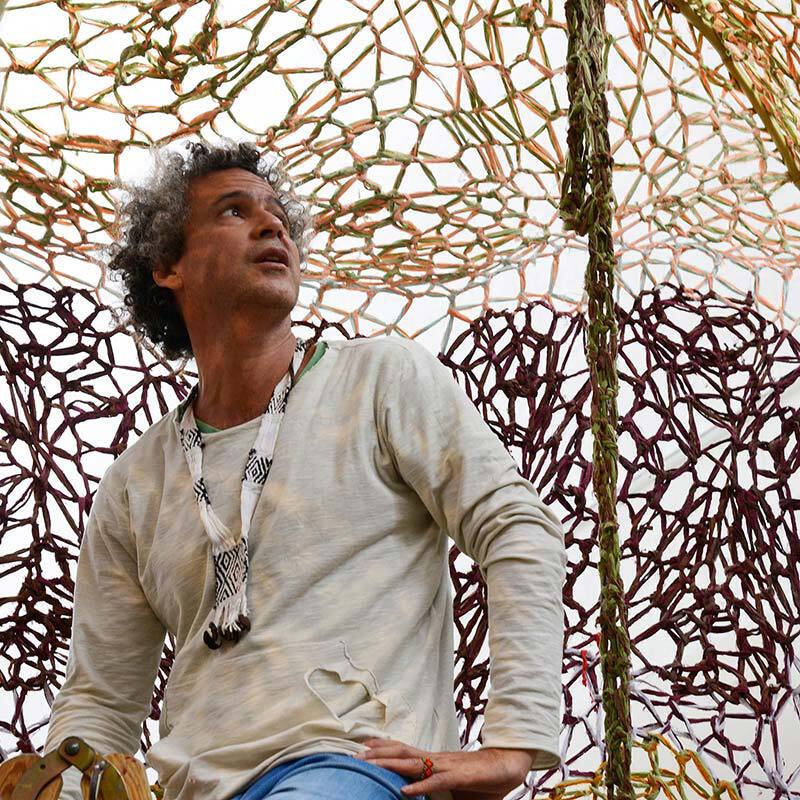

From turning his artistic practice into a business via the blockchain to fitting his paintings with GPS trackers to see where they go after they’re sold, Jonas Lund is best known for making shrewd and irreverent works that utilise the technology of the day to highlight the unseen processes and networks at play in the art world and beyond. Collectors Agenda visited Lund in December as he prepared for the launch of the installation-cum-performance Operation Earnest Voice, which took place at the Photographers' Gallery 10-13 January.

Jonas, you’re often referred to as a net artist but your background is in photography. How did you start making online works?

I used to study photography at the Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam and then I stopped because I was really uninspired by the limitations of the medium. I started to make websites, program, and get into creating online works as a way of being more in tune with current contemporary culture. From a social and political level nothing is untouched by social media and the Internet – whole cities change because of them.

Would you say, then, that boredom and restlessness are factors that drive your practice?

For better or worse, I seem to never repeat myself or stick with the same work for too long because I need to challenge myself every time, otherwise it gets tedious and uninspiring. It seems that my ultimate goal in making art is to keep myself entertained – to find a balance between boredom and stress.

And making net art kept you entertained?

The traditional production method with photography at that time was to think of a piece or a project for a long time and then make it real as a sculptural thing and then that’s the work. Whereas, if you make net art, you sit on your couch and you think of some clever ideas and then you write some code and instantly it’s everywhere. The speed of the process was very encouraging and very powerful. You publish early, often, and everywhere

When you were starting out, were you influenced by the first wave of Internet art?

Not really. When I was working with photography, which has a pretty rich history, I never felt completely comfortable because there is so much that you have to relate to. When I was starting to make net art, I allowed myself to be intentionally naïve, and not looking into it gave me freedom to do whatever I wanted, which is pretty ignorant but ignorance as a strategy.

It sounds like that attitude made you less of a purist when it comes to what constitutes Internet art.

Being a purist seems to be a weird regression into protectionism. I was never very committed to only making online work. I consider all of my work to be net art, whether it’s in a gallery or not. The project I’m currently working on, Operation Earnest Voice, is 100% net art because it exists in a network so it deals with network structures.

What can you tell us about "Operation Earnest Voice"?

Basically, I’m going to set up my own propaganda office/influencing agency with twelve employees and use every trick in the book – fake identities, fake accounts, fake news, fake everything – for the duration of 4 days to try and reverse Brexit. I’m just about to launch the recruitment process.

What kind of people are you looking to hire?

They will be image-makers, meme-makers, hackers, programmers, trolls, social media managers, narrative production specialists, Brexit specialists, psychological warfare specialists, celebrities, and politicians – anyone you can think of.

So will you be using them to spreading positive information about the EU?

No because that obviously won’t work. I think the primary strategy is to develop an outrageous narrative, whether it’s true or not – something that’s outrageous enough for a ship to change its course. I don’t know if it’s even possible to produce a narrative like that any more because it seems like the world is immune to outrageous facts.

How serious is this attempt?

Obviously, the performance/installation is a bit tongue-in-cheek, but I’m very seriously attempting to do it. For me, it’s a way to try and explore different aspects of decision-making processes and the manufacturing or engineering of consent through social media, which I’ve done some works on before. This time, I’ll be able to use all The Photographers’ Gallery’s media channels as well, so it’s a pretty good platform to explore how much you can accomplish. The tools that the state-sponsored propaganda offices – Operation Earnest Voice is based on the American version of such an office – used to be reserved for states because of the cost. Traditional media like broadcast media was reserved for very few people – but now with computational politics, politics informed by algorithms, modelling and big data, databases, really detailed statistics on what people do, the tools have been somewhat democratised; they’re available to you and me on a totally different level. Everyone can use Facebook adverts – it’s not restricted – and everyone can participate in social media, and if you have a voice or a clever campaign you can create something that can be manipulated to reach a broad audience.

Many of your works highlight the “quid pro quo” nature of the art world. In the 2016 installation Your Logo Here, for example, institutions could “sponsor” the exhibition and get their logo printed onto your works. In Jonas Lund Token (JLT), where you created 100,000 shares in your artistic practice, you’ve taken this idea one step further by allowing shareholders to vote on proposals related to your practice, why?

It’s a way to, again, find different optimised decision-making processes. The question is basically how do you reach a strategic decision? How can you incentivise making strategic decisions? Can you create a distributed board of trustees, board members, and participants in your artistic practice, who don’t only give you advice based on their goodwill and their desire to help you out but also because they have a financial incentive to encourage your career?

How does that function on a practical level?

Each share gives you one vote for proposals that I’m currently making. I’m still the majority shareholder, so of course people vote and participate, but it’s more on a conceptual level because the tokens are still being distributed. The future projection of where I want to take the project is that as soon as someone sits on more than 1000 tokens they can also make proposals that the board then gets to vote on. That way my practice can become decentralised and autonomous and I don’t have to do anything. I remove myself from the work.

Participants are awarded “Jonas Lund Tokens” for things like writing a positive review of your work in an art magazine. Is this intended as a critique of the way the art world functions? I’ve made quite a lot of work about the art world because of that fact that it’s so opaque. It’s the greatest hierarchical power structure network ever! And it governs over so much cultural influence; very few people on top decide the fate for the vast majority. The tokens are a reflection on that invisible exchange. I do something for you; you do something for me. But it’s also to give incentives for participation. It’s both. A lot of my work is like, yes, you can gave the cake and eat it too. You critique the system that feeds you.

JLT is a crypto currency, like Bitcoin, and as such it is distributed via the Ethereum blockchain. You’re one of a growing number of artists to use this technology to create art works. What do you think about the potential of so-called “crypto-art”?

I’ve yet to see some really ground breaking application for blockchain technology where I can say, “Oh my god, that’s amazing,” so I’m not sure. It’s a technology and it offers you certain possibilities and has certain consequences and implications for what it allows you to do and what it doesn’t allow you to do. I’m definitely not a crypto believer at all. Currently, Bitcoin blockchain technology consumes as much energy as Denmark on a daily basis, which is rather wasteful to say the least – and to do what, to have a distributed database? You can design a smarter system for that. In fact, it already exists and it’s called the banking system.

What do you consider to be the role of performance in your practice?

I think most of the works have a very strong performative aspect to them. I mean, every time I make a proposal and people vote it’s a sort of performance. It’s the same with my text-based paintings that say things like “this painting must never be sold at auction” – it’s a never-ending contract-based performance.

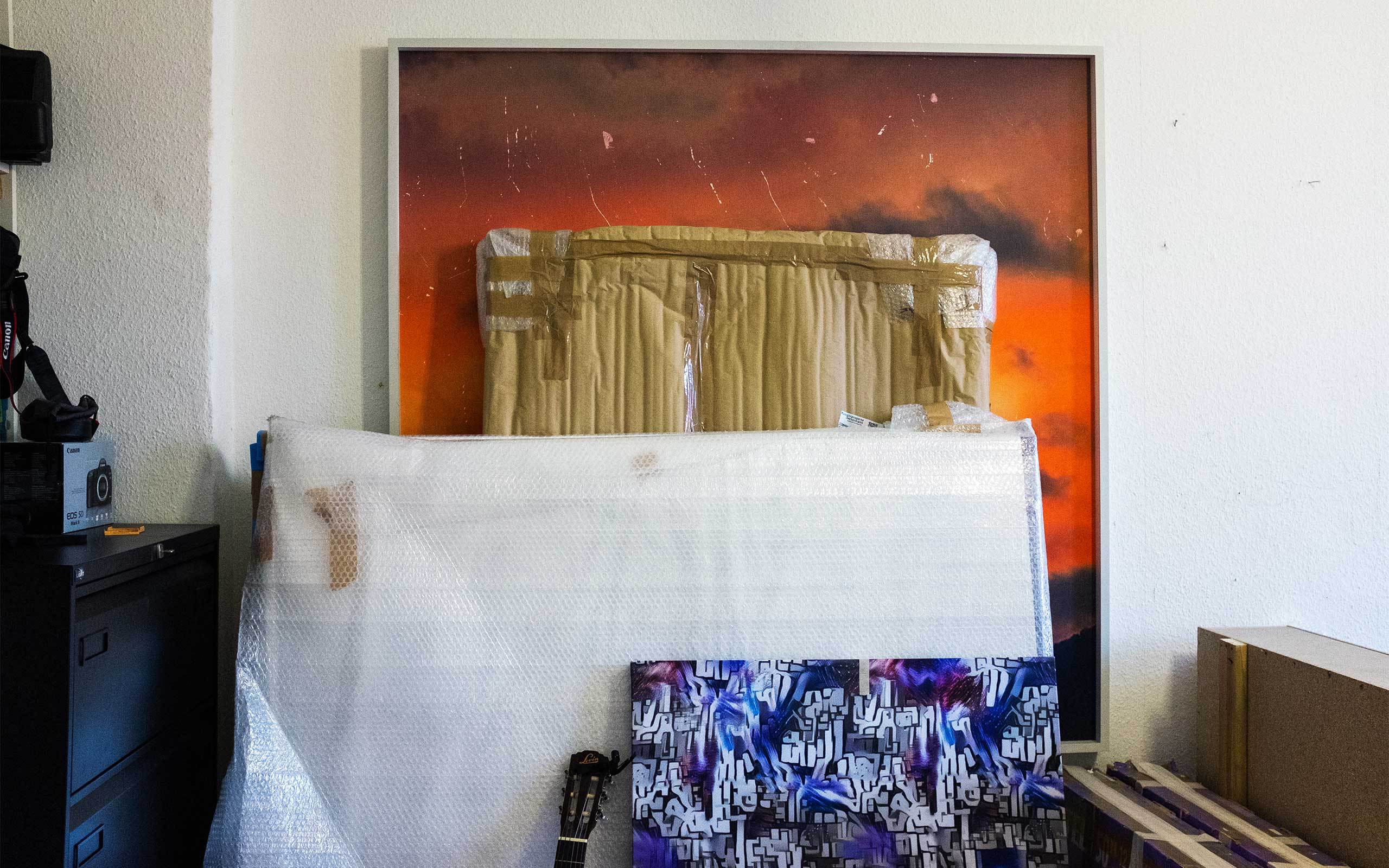

If it’s a performance, is it important for you what these paintings actually look like?

Aesthetic value becomes very important from a personal point of view – having a joy in the making of the visual – but they also need to function as art works; as art objects. For example, the paintings with GPS trackers (from the 2014 series Flip City), in order for them to perform they need to be sold and in order to be sold they need to be attractive; they need to work as paintings in their own right. With the text-based paintings, the text that’s hand painted by a sign painter needs to be wobbly; you need to have the touch of the artist because if it’s only concept, concept, concept then everything is perfectly understandable, all of the magic is gone and they’re really boring.

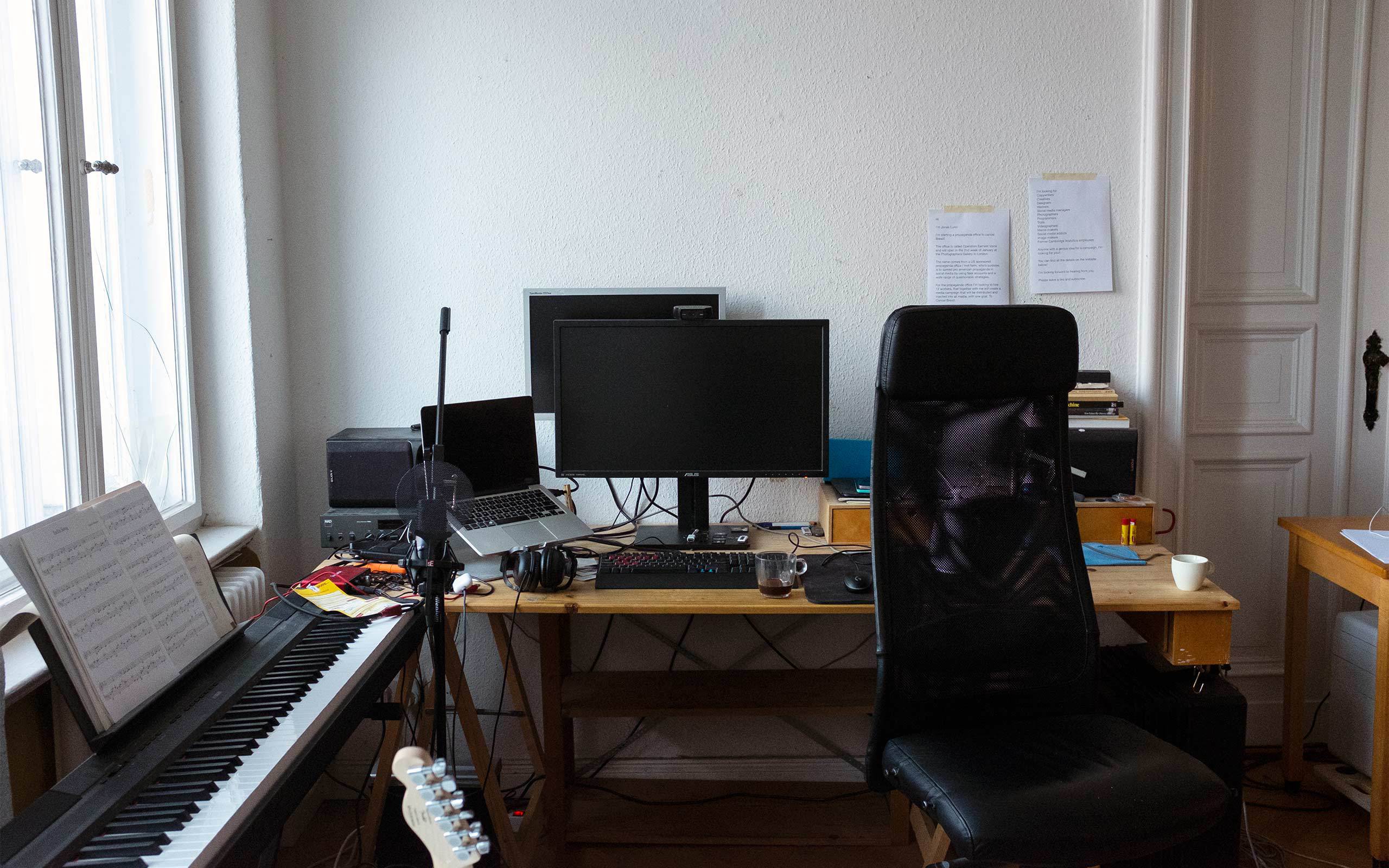

There are a lot of musical instruments in your studio but, as far as I’m aware, music has never really factored into your work. Is there a reason for that?

It’s not necessary something that I keep separate from my practice, but I just didn’t decide to make a song yet. I wanted to make a cover album, at some point, for fun.

What kind of covers?

I’d obviously outsource the selection (laughs). I like playing music a lot. I used to play when I was young – very poorly – and I started taking classes again last year. The process of how you learn is so different from artistic practice. What it does to your brain is extremely satisfying because you basically have instant feedback whether what you’re doing is good or not. If you practice something on the piano you know instantly if the note you play is wrong, and there is great satisfaction in the immediacy of knowing, which with an artistic practice you don’t get.

Interview: Chloe Stead

Photos: Franziska Rieder

Links: untitled projects, Vienna