The Mexican Jose Dávila considers himself a self-taught artist. His intuitive research into art history led to his series of Cutouts, where he modified images of well-known artworks. Today, he is mainly known for his sculptures, often on a large scale, in which he explores notions of precarious balance. He works in multiple disciplines and concepts; painting, drawing, prints and public art projects encompass his artistic output.

Jose, you are a well-known artist today, but you never trained as such. How did you know you would become an artist?

I knew I wanted to be an artist since an early age. I had cancer when I was a child, I had a suprarenal gland removed. Therefore, at school, I was not allowed to play in the schoolyard with the other kids so I wouldn’t get hurt. Instead, I went to the art room instead, drawing or sculpting with plasticine, while watching them play outside. This may sound sad, but I was happy there. It made me realize I could put my mind and my heart in a different place.

It sounds like you were a natural…

Yes, being an artist came naturally to me. However, the art school here in Guadalajara was not what I was looking for, the architectural school seemed more appealing. But right from the start, I went straight to all the special drawing classes… Long before finishing my studies, I knew I would not be an architect.

Was there a moment when you thought: this is it, I am a bona fide artist?

Yes. I think I had a moment back in 2000; during a 2-week art residency in the UK. My project was to build my own studio up on a hill. And there came this instant when everything was just falling into place, and I knew: yes, this is it. There was no mistake about it. But the worrisome question was: will I ever be able to make a living? It’s great to find your purpose but daunting too.

Daunting could also be describing your sculptural work today – a stone that is just about to fall off a plinth, a marble slab that is held from crashing down by sturdy straps, all in precarious balance. Where does this want for equilibrium come from?

It came from personal experience; I was trying to achieve balance in my life. From there I realized balance is also an empathy between different objects and materials. If the parts are not working together, if they are not communicating, the whole structure falls apart. Putting this thought into practice, I understood that a sculpture is dispositive: it is more of an event than an object. Different realities should adapt to each other with the goal to be empathic and to create a physical balance against the force of gravity.

Do you feel our world is out of balance, and you need to put it right?

Yes. Mexico for example is a very unbalanced country in many ways. We have beautiful natural resources, but we pollute them horribly. We have a lot of wealth overall, but it is in the hands of only a few people. We have a great history, but we tend to deny it. I think this unbalance is part of our culture. When I was going through a process of psychotherapy, a need for personal balance, equilibrium and gravitas emerged. These thoughts translated organically into my work. I need it to have some weight to be grounded.

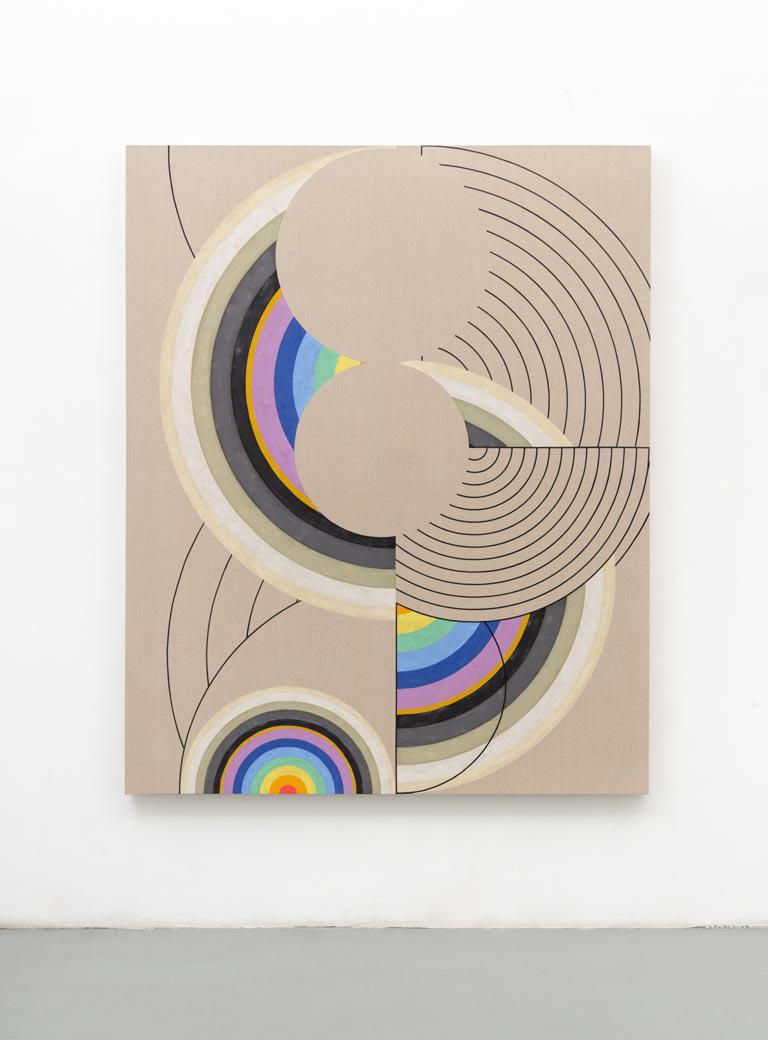

The fact of constantly returning to the same point or situation, 2021, Silkscreen print and vinyl paint on loomstate linen Courtesy of the artist and Sean Kelly, New York. Photo by Agustín Arce © 2022

How is your working process?

It is intuitive. As a younger artist, I was trying to understand the core nature of why I made what I made. It may sound odd, but it is in in that process of trying to understand what you are doing that you start discovering what it is. At least, this is how I discover the meaning of my work.

What happens next?

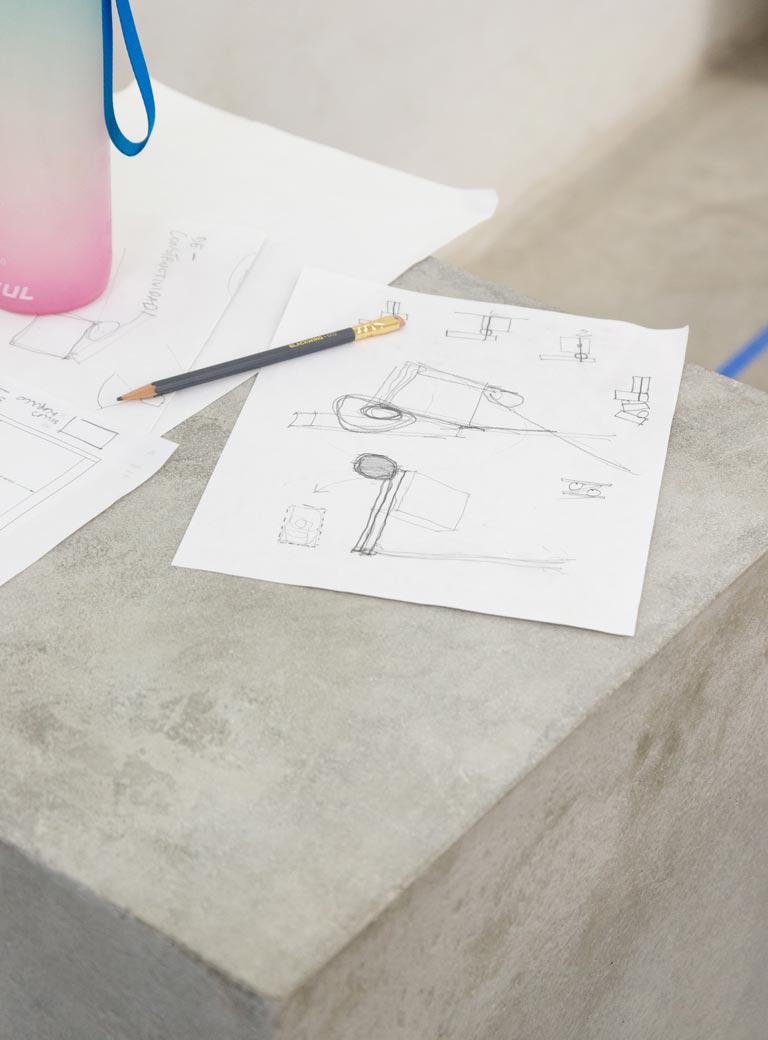

The process becomes more consciously overt. With a general idea in mind, I start sketching sculptures. However, once I try to translate these sketches into a real object, I tend to encounter a lot of challenges. Then I improvise and end up creating a new work. The sketch is more like a tarmac to help me take off. While crafting the sculpture I need certain things – or the sculpture needs certain things – and in the process of supplying them the final work arises.

Some of your sculptures are on a huge scale – how do you put them together?

It is like a ballet and somehow looks like a 16th century painting of people moving around a Madonna or such. It is a ritual: about eight people move something very heavy, put it into place, and transform it into a very real result.

Does your team follow your sketches when putting up the sculptures?

I do sketches, but then it’s easy to draw a line on a paper. It becomes much more difficult once weight comes into the equation. And I don’t use tricks, I don’t hide the structural underpinnings. As I said, balance is crucial to me. I want my work to be real, so the process is a very simple one. It goes: Let’s move this rock 1 cm at the time, until it loses its balance, then move it back again to the last point of support. The creation happens on the spot.

Like a performance?

Yes. It’s a very empirical way of working with limits. And after we find the real balance, we safeguard the works for security or liability reasons, but that I only see as a consolidation.

Does math come into the equation?

I use more of an empirical way of understanding how materials react and behave. How weight wants to behave, in the sense of gravity. But in many cases, once I finish a sculpture in the studio, I call in an engineer to calculate if it’s safe. It’s funny because it is the opposite process of what an architect would do. I’m turning architecture upside down, so to speak.

For some of these sculptures, you use stones that you find on the location of the exhibition. You don’t bring them over from Guadalajara. Why?

There is the obvious reason about being mindful of resources, to not make heavy stones travel by plane. But it is more than just that: in a conceptual way, it is interesting to find peculiarities. We might think a rock is just a rock, but that is not true. Rocks embody the genealogy of their place of origin, they are historical depositaries of thousands of years. They convey a spirit that I like to tap into.

After an exhibition, you sometimes return the marble slabs you used to the quarry. When you dismantle your work, doesn’t it cease to exist?

My sculptures are conceptual constructions. These marble slabs or sheets of glass are only an artwork for as long as the pieces are performing together, in a certain position, in a certain conjugation with each other. But once you dismantle it, the sculpture becomes just one marble slab or one sheet of glass again. The glass might be used for a window, the marble might end up in a bathroom... It is only when they are put together and performing a specific task that the artwork happens: this is what I mean when I talk about a sculpture as an event.

Is it more about the act of creation and less about the materials that you use? In the sense that even a bottle rack could be art?

Exactly! My sculptures have a lot to do with Duchamp’s idea of the readymade. It is art because it is being art in that moment. Objects, depending on the activity they are performing, can take on different meanings. This leads to the idea of the artist as a skilled transformer of objects. The sculpture is not just that specific piece of marble or glass or rock, but the way of intertwining all these elements. This means I can do it again. It will be the same sculpture, because the dispositive is the same.

But does it have to be you who puts the sculpture together again, or could that be anybody?

Anybody really! I create very specific instructions on how to construct my sculptures. I even write down something resembling IKEA instructions, I record step by step tutorials…. My work is a blueprint, the related sculptures can be built in a hundred years from now by people I don’t know. But it will still be “my” art.

Objet du voyageur (The traveler’s item), 2021, Concrete and metal Courtesy of the artist and Sean Kelly, New York. Photo by Agustín Arce © 2021

A different, earlier body of work are your cutouts: well-known pictures of paintings that are missing a key piece. Do they reference your research in art history?

Yes. I was reading a lot of art books and there was this imagery about art and art history. I started cutting out images, scanning and scaling them, working with them. They are an important part of my practice because they represent the research I do.

Let’s take your cutout representing the famous motif of the Demoiselles d’Avignon. Do you see yourself continuing in a line that started with Delacroix, and inspired Picasso and Liechtenstein, who both did versions of the painting?

Absolutely. In the beginning, when I was looking at these pictures of works of art, I enjoyed learning about the artists or sculptors. Later I realized many artists have done exactly that: check out the work of other artists, even paraphrasing them. That led me to focus on using images of these artists, to try and create a continuity. Like Liechtenstein, who used comics, or Richard Prince, who appropriated cowboys and the Marlboro man, or Picasso, who continuously referred art history.

People may wonder: What do your cutouts have to do with your sculptures?

Well – they are being made by the same person! But joke aside: the cut-outs have a connection to my sculptures. My sculptures have a precarious balance, and you could imagine what would happen if they broke down. The cutout is also very much about imagination. After all, it is a well-known picture that is missing a part – so automatically, you are trying to fill the void. Either by memory, if you know the image, or by imagination, because you wonder what is there. To use the artwork as a dispositive to trigger people’s minds and imagination is basically what I do, and it is just the same whether I do cutouts or sculptures.

At the recent Biennale de Lyon 2022, you exhibited sculptures incorporating furniture. Was this your first time working with tables and chairs?

Yes, in terms of creating precarious balance, it was the first time. I think the reason the curators of the Biennale chose that piece was because they saw it around the time of the pandemic. It struck a chord, as our interactions with our surroundings were so very limited then. You could only be with the objects close to you, those very domestic objects that ended up creating this work.

La science, comme la réalité, reste platonicienne, 2022, Concrete, wood, rocks, and ratchet strap Installation view at the 16th Biennale de Lyon, FR Courtesy of the artist and the Biennale de Lyon. Photo by Blaise Adilon © 2022

How did you experience the lockdowns?

I am aware that many people had a rough time, but my personal experience was more joyful. With my wife and daughter, I went to my little house about two hours away from Guadalajara in the middle of nowhere and it was fantastic. It felt like a gift to have to change my habits. It was scary though in the beginning, because in an apocalyptic situation, art will be irrelevant. But I realized I could be a farmer up here, so I had something to fall back on which gave me peace of mind.

You said you were concerned art might become irrelevant. Is that why recently you tried your hand at NFTs?

Actually, I did it out of sheer curiosity. And to be honest, I didn’t love it. I guess I am still into an analogue experience of art… But I see NFTs as an interesting medium offering more ways to experience art, and if art reflects its time – and good art always does – I wanted to see what our digital era generates. The only way to understand it was to do it! But NFTs are somehow still at a very early stage, they won’t supplant existing art. Also, taking into consideration the energy that minting consumes, it did not work for me. It will probably be a one-off.

No more NFTs then, but obviously you will continue to do cutouts and sculptures. How do you decide what media is the best to get your ideas across?

It is a very intuitive decision. I don’t have a specific planning, even less a strategy. I leave it to be an organic process guided by my interest, I don’t know exactly what will happen…

That sounds almost unorganized, but I suspect that you are just the opposite?

Yes! When people come for a studio visit, they remark – it is a comment always, a misconception really – on how my studio is so organized! Sometimes I don’t know whether it is a compliment or a reproach. But artists must be organized! All professional people know that.

You still live and work in your hometown Guadalajara – have you never thought of moving now that you are an international artist?

Good question – even here, people ask me why I don’t at least live in Mexico City. But in my hometown, I do find a lot of peace, retreat, and free time. Guadalajara may be an ugly city in many ways, but I like it, and I like the way I work here.

Would you describe your work as Mexican?

At the first glance, my work does not look Mexican in the sense that it is not folkloric. But I think it is very Mexican in its soul and in the way I make it. Because in my country, people are ingenious. You must be, because you always need to be able to work out things by yourself, like fix your TV. I think in that ingenious way my work is definitely Mexican.

Aside from ingenious Mexicans, who are your inspirations?

It is a difficult question, as it changes so much according to the phase I find myself in. I have been inspired by Helio Oiticica, Robert Smithson, Hilma af Klint, Lygia Pape, Sol LeWitt or Gordon Matta-Clark. There is Pierre Huyghe, too; generally, I am aware of other living artists in my age range doing interesting things.

Tell me about your latest series, the circle paintings.

When I was a child, I painted all the time. But once I wanted to engage with art in a professional way, I discarded painting because it was related to what I did as a child. But now, after 20 years of working as professional artist, I see it differently. During the pandemic, without being able to go to my studio, painting was the one thing that I could do. With my daughter, I was playing this game of trying to draw the perfect circle. By the way, it is almost impossible! I then started researching, and the circle has always been there, present in all the paintings over the centuries. It is the perfect balance, which of course taps into my art. I started painting it without even realizing.

You will keep up the painting?

Yes! Because the circle never ends! I expect to paint forever.

Untitled (Femme assise au chapeau plat), 2019, Archival pigment print Courtesy of the artist and OMR gallery, Mexico City. Photo by Agustín Arce © 2019

Untitled (Drowning Girl), 2020, Archival pigment print Courtesy of the artist and König Galerie, Berlin, DE. Photo by Agustín Arce © 2021

Untitled, 2013, Archival pigment print Courtesy of the artist and Travesía Cuatro, Madrid, SP. Photo by Agustín Arce © 2021

Interview: Alexandra Markl

Photos: Agustín Arce