A film showing the Arctic night in drone light, deserted palm oil plantations accompanied by technoid sounds, or photographs in which the traces of nuclear test sites become visible – the French-Swiss artist Julian Charrière is an important voice of socially engaged contemporary art. His work is playful and characterized by a great variety of artistic approaches – from film to sculpture to photography. His themes are serious, as he deals with climate change, environmental damage, and the exploitation of the earth. Collectors Agenda met him. In our conversation, we talked about nature as a source of artistic inspiration, traveling in times of the pandemic, and the fragile beauty of the polar ice caps.

Julian, you were nominated for the Prix Marcel Duchamp in 2021 and exhibited at the Centre Pompidou in Paris in the exhibition Weight of Shadows (Le Poids des Ombres). What did you show there?

For the exhibition at the Centre Pompidou, I have conceived an immersive installation that is a result of one and a half years work on chemical cycles, with air as a medium that flows through us, but through which we also move.

What inspired you to do this?

I had a key experience when I was standing on the Greenland ice caps while we were shooting my film Towards No Earthly Pole (2019) and I suddenly became aware that there is actually sky under my feet and also above my head, that I was flying, even though I could feel the solid ground beneath me. In fact, I was aware that I was into history, millennia trapped in ice, stratum by stratum – but what kind of history? The temporalities stored in the ice are tiny bubbles of air – this is the only place where the changing composition of the atmosphere is recorded. So I was standing on the memory of the sky. This feeling, and having been in a place where sky and earth seem to blur visually, has stayed with me. At the same time, the glaciers are melting beneath my feet, and with them the little bubbles that contain the history of the sky are released back into the atmosphere. A cycle that begins with the burning of the fossil raw materials dug out of the earth and shows that if these heavy particles are flung out of the earth into the sky in excess, it too must be mineral.

What have you developed from this approach?

I made it my business to “mine” substances from the sky by reversing the conventional mining process. Instead of extracting fossil raw materials from the earth’s interior, as is usually done, I captured CO2 from the surrounding air using a special technical process developed by a team of scientists at the ETH Zurich. This repertoire was then expanded to include the CO2-rich exhalations of people around the world, which were collected in inflated balloons. This was the starting point for an alchemical transformation of the gas into the hardest naturally occurring material on earth: diamond. I took the stones back to the polar caps in Greenland. An allegory for the possibility of closing the carbon cycles we have opened. And this action in Greenland is at the center of my video work Pure Waste (2021), around the idea of which the exhibition for the Prix Marcel Duchamp at the Centre Pompidou revolves. It is presented on delicate paper that moves easily in an immersive, expansive installation. A black floor of anthracite polished to a high gloss, extends across the entire space, mirroring the ceiling, visitors, and sculptures. I have created columns that extend below the ceiling, based on oil drill bits (Le Poids des Ombres, 2021). A sculpture made from another drill head (Touching the Void, 2021), with a single diamond embedded in its tip, hangs like a Sword of Damocles above the visitors’ heads. Everything is meant to show the foundations of our society, which have been based on coal since the industrial revolution, and at the same time the position of man in an atmosphere where the essence of the earth’s soil is in the surrounding air due to the excessive demand for the burning of raw materials.

You studied art at the ECAV [École cantonale d’art du Valais] in Valais, Switzerland, and at the Universität der Künste (UdK) in Berlin. What was it like for you to study art?

I was at the ECAV only for a very short time, for one year. It was a kind of in-between year, because I had always wanted to go to Berlin. I was only 17 at the time, and in Berlin they told me, “You’re actually too young for school.” In retrospect, though, I’m very happy about that year and appreciate the experiences that came out of it. The ECAV is located in Valais in the mountains. I spent a lot of time studying Land Art and its present heritage, especially how to navigate that heritage, which gave me a strong interest in the outdoors and in interacting directly with my surroundings. However, it remained my goal to come to Berlin, where I was accepted at the UdK in the following year. I was very fortunate that Ólafur Elíasson became a professor at UdK, founded the Institute for Spatial Experiments, and was more than just a good professor. He simply has a good eye for artists and put together a group of terrific participants. The close connection to his studio allowed me to see for the first time how such a huge studio works, which was totally abstract for me before. I have to say that I have always been very curious, but Ólafur broadened my horizons even more. We had to deal with very different professionals, from break-dancers to nanoscientists to architects. And now, ten years later, I still share my studio with some of the other participants, which shows how significant that time was and still is for me.

In your art, you address the serious encroachment of humans on natural habitats. What role does the relationship between nature and man play in your art?

Certainly, an important point in my art is the dichotomy between culture and nature, in the inheritance of which we stand and of which we are perhaps also the victims: this division of two worlds, which has begun to developed since the beginning of monotheism and was taken to extremes in Romanticism. In my work, however, I try less to address the mutual attacks and more to explain the connections between these two positions, always taking into account what is perceived as nature or culture and what is perhaps also mistakenly perceived as one of the two, because we are moving here in the midst of categories of human definitions. What is interesting about this relationship between humans and nature is the terminology alone, the vocabulary we use. In both German and English we use words like “environment,” “surroundings,” or “being surrounded by,” which implies that we are in the center and perceive something else around us. And my art is not about a separation between the two forces: what is human and what is not human. It is rather about, and now I use the French term, “milieu,” which I use to refer to an ecosystem. It is about a network of forces that influence each other, and these interactions lead to the world as we know it today. Nevertheless, I naturally also like to deal with places that at first glance look as if they have suffered from deep human intervention, for example Bikini Atoll. In several works I show the effects of these interventions, but now you also see how these areas can recover, heal, completely free of human influence, simply because humans are no longer there.

You recently described yourself as a future archeologist. What do you understand by that?

That’s not really correct. The term came up a lot, and I actually find it quite amusing, but I would never call myself that. However, it is quite clear that time plays a central role in many of my works, and many of my works also deal with the present and how this present is influenced by the past and how both together determine the future. The idea that the linear progression of time cannot work, is important to me, because history is not written, it is always rewriting itself. If we interpret the past differently today, there is feedback that changes the present and ultimately, of course, the future. In my work, I often look at such places, where points of time axes intersect and create something new. Places where you feel tension, where you know that a lot is happening that possibly plays a big role in the future. The work Future Fossil Spaces (2014-2017), for example, which was exhibited at the Venice Biennale, is, as a sculpture, a mode where a multitude of effective forces and their respective temporalities meet. In this context, I can mention only a few now, such as those of the dried ancient sea, the microorganisms fossilized in the salt crystal, the denser oceanic lithosphere, obviously lithium as a material and its potential energy, and last but not least the viewers who encounter the work in the exhibition. This very specific node exists in its immediacy, but the trajectories of all the different timelines extend into both the past and the future. That is why the term future archaeologist is not really correct; if anything, it is more the image of an archaeologist of the present, but then one must also be able to project into the near future.

Does art need to reflect climate change more as an issue?

The power of art is that it doesn’t actually have to do anything at all. Its radical nature and equally its great quality lie in the fact that it can free itself from any mission. Nevertheless, I think that today, in the midst of the climate crisis, every inhabitant of this world should deal with such questions and in part also draw consequences in corresponding ways of life. Of course, art can also contribute to bringing the topic closer to a broader mass in a different way, and perhaps has strengths compared to other mediating media. Climate change is very abstract and complicated to understand in the first place, because it stretches beyond what our perception can conceive, and in the process it is often reduced to simple concepts and words that may not be able to adequately represent this complexity. I think that art has completely different possibilities to open up spaces and address modes of perception, to demand confrontation.

How does your work differ from and resemble a scientific cognitive process?

Basically, they are completely different methods. Maybe there are a few overlaps in the field research that I also do. But I am absolutely free of any results, and I don’t have to prove anything at all. Art can be pure speculation and fiction, and that is what interests me. I can operate in this sphere and thus also change reality, through these very fictions that art can contribute. And yes, science is about results. But the very important point is actually that artists and scientists always doubt. Here we are very similar, because we express doubts and because we are constantly questioning, which makes us very connected. So it also becomes clear that there is clearly a creative process behind both disciplines, because the constant questioning of what is perceived as reality and described as such by society is a motor that drives us forward, not necessarily forward in the sense of capitalist thinking, but in the sense that it sets other existential problems in motion and opens up a discourse.

In 2019 you made the film Towards No Earthly Pole. What fascinates you about the polar regions?

Above all, the film shows the limits of our perception, especially when it comes to the understanding of something that is shaped by collective ideas. For me, the Arctic is a place that, like few others, carries an image of itself from the common forms of representation. In recent years, this has changed from something overwhelming, uncanny, and unapproachable to something fragile, almost in sync with the ever-increasing presence of climate change. Two perceptions that both fall under the heading of “natural”, only it becomes clear that what we call “nature” is a product of what we would define as “culture”. This is a factor that fascinates me and was also the conceptual starting point for Towards No Earthly Pole. Because when we think of the Arctic, images of blue icebergs, mostly in sunlight, come to mind, which we perceive as representatives in the fight against climate change. But the polar night is not yet anchored in our collective memory; it is almost like a blackout, which I wanted to bring into our consciousness with the film.

Which natural space in the world inspires you the most?

I can only speak of my current interest here, because that changes all the time. I am particularly interested in the abyssal regions of the seas; they are perhaps what I am dreaming of at the moment. But there is no landscape or place that has more value for me than the other. The deep abysses are interesting, however, because they exist in the absolute absence of light, outside the space of our perception. And not even just because of visibility, but because of the pressure in these depths that we could never endure. It is the space in which everything is possible because we cannot experience it, but we can think everything into it.

Julian Charrière, Towards No Earthly Pole – Byrd, 2019, Copyright the artist; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, Germany

Julian Charrière, Towards No Earthly Pole, 2019, Film Still, Copyright the artist; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, Germany

Julian Charrière, Towards No Earthly Pole, 2019, Film Still, Copyright the artist; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, Germany

Your art is created all over the world. It involves a lot of travelling. Will you work differently in the future?

I am firmly convinced that travel continues to be important in the first instance, but that one should already think three times before embarking on a journey and also deal with travel differently, for example by using other means of transport, such as trains. But actually, the beauty of the idea of a globalized world is not an open economy, but open humanity in relationships that transcend borders. For this, travel is also necessary. Today, more than ever, we need to feel communal, because that is the only way to solve common problems, including the climate crisis, for example. We have a global problem here that cannot be tackled if it is only thought of locally. In my opinion, global communication, but also physical solidarity, is essential if we want to live in a society that feels and acts like a community. Especially now, during the Corona crisis, we have noticed that sedentariness promotes patriotism and extremism and that closed borders encourage nation-state thinking. This goes against everything I believe in and stand for. That’s why I think travel is important and that a globally connected world is something we can be happy about today.

Did you also make art during the Corona Lockdown?

For Pure Waste, I started an action that was particularly symbolic in the time of the pandemic outbreak, when community was questioned, travel was banned, and borders became more and more important. I sent balloons to friends and acquaintances worldwide and asked them for their exhalations, which were then collected in my studio in Berlin for further processing. The occasion for me here was in any case the fact that we were in a situation in which we could not be mobile or, rather, in which we were not allowed to move at all. It is the air that connects us all, no matter how far apart we are, no matter what lies between us. We are all connected by something we can neither touch nor see. This was the impetus for me to involve the community and to find a way to let breath overcome borders.

What projects have you worked on recently?

Most recently I worked on an exhibition at Gallery Tschudi, which is particularly close to my heart because for the first time I am exhibiting with an artist and at the same time friend who inspires me a lot, Katie Paterson. The title is Vertigobecause the exhibition is about times and temporalities that go beyond what is imaginable. When you think about them, there is this moment of imbalance and powerlessness. In addition to existing works that we have set in dialogue, new productions are of course also represented. For example, I created a series of photogravures, Limen(2021), for which I made pigments from earth samples from the glacier regions of North Greenland. In three colors I printed photographs of places where the boundaries between sky and earth seem to merge. In the process, the real ground becomes the image, a kind of sedimentation of the visual realm.

What projects and exhibitions are coming up?

Well, there’s a lot coming up. Among other things, there will be a solo exhibition at SFMOMA in San Francisco; I will participate in the Lyon Biennale and be in Venice with Parasol Unit, where I will show a contribution in the exhibition Uncombed, Unforeseen, Unconstrained, a side event of the 59th International Art Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2022, and above all I am working on a large solo exhibition at the Langen Foundation in Neuss, which will open in September 2022.

Julian Charrière, Future Fossil Spaces, 2017, Installation view / Details, La Biennale di Venezia, Arsenale, 57th International Art Exhibition, Viva Arte Viva, Photo: Jens Ziehe, Copyright the artist; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, Germany

Julian Charrière, Future Fossil Spaces, 2017, Installation view / Details, La Biennale di Venezia, Arsenale, 57th International Art Exhibition, Viva Arte Viva, Photo: Jens Ziehe, Copyright the artist; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, Germany

Julian Charrière, Weight of Shadows, 2021; Installation Views / Details, Prix Marcel Duchamp 2021, Centre Pompidou, Paris, France, 2021, Copyright the artist; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, Germany, Photo by Jens Ziehe

Julian Charrière, Weight of Shadows, 2021; Installation Views / Details, Prix Marcel Duchamp 2021, Centre Pompidou, Paris, France, 2021, Copyright the artist; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, Germany, Photo by Jens Ziehe

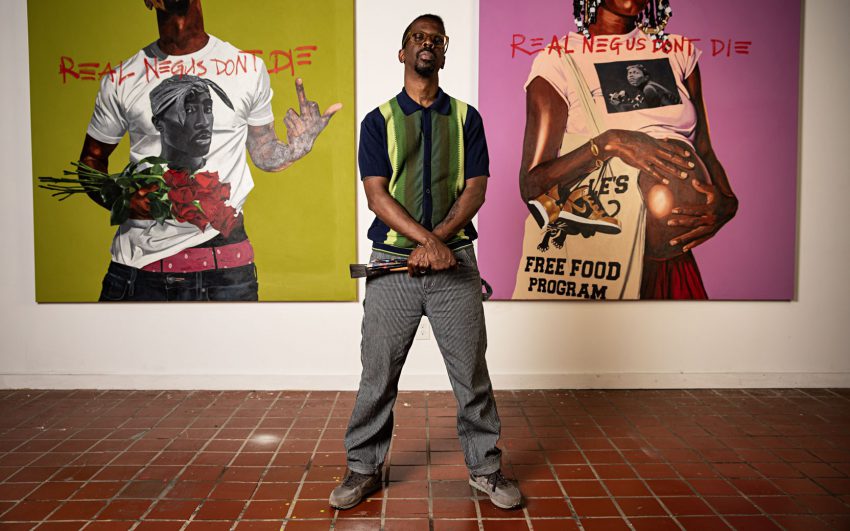

Interview: Kevin Hanscke

Photos: Nora Heinisch