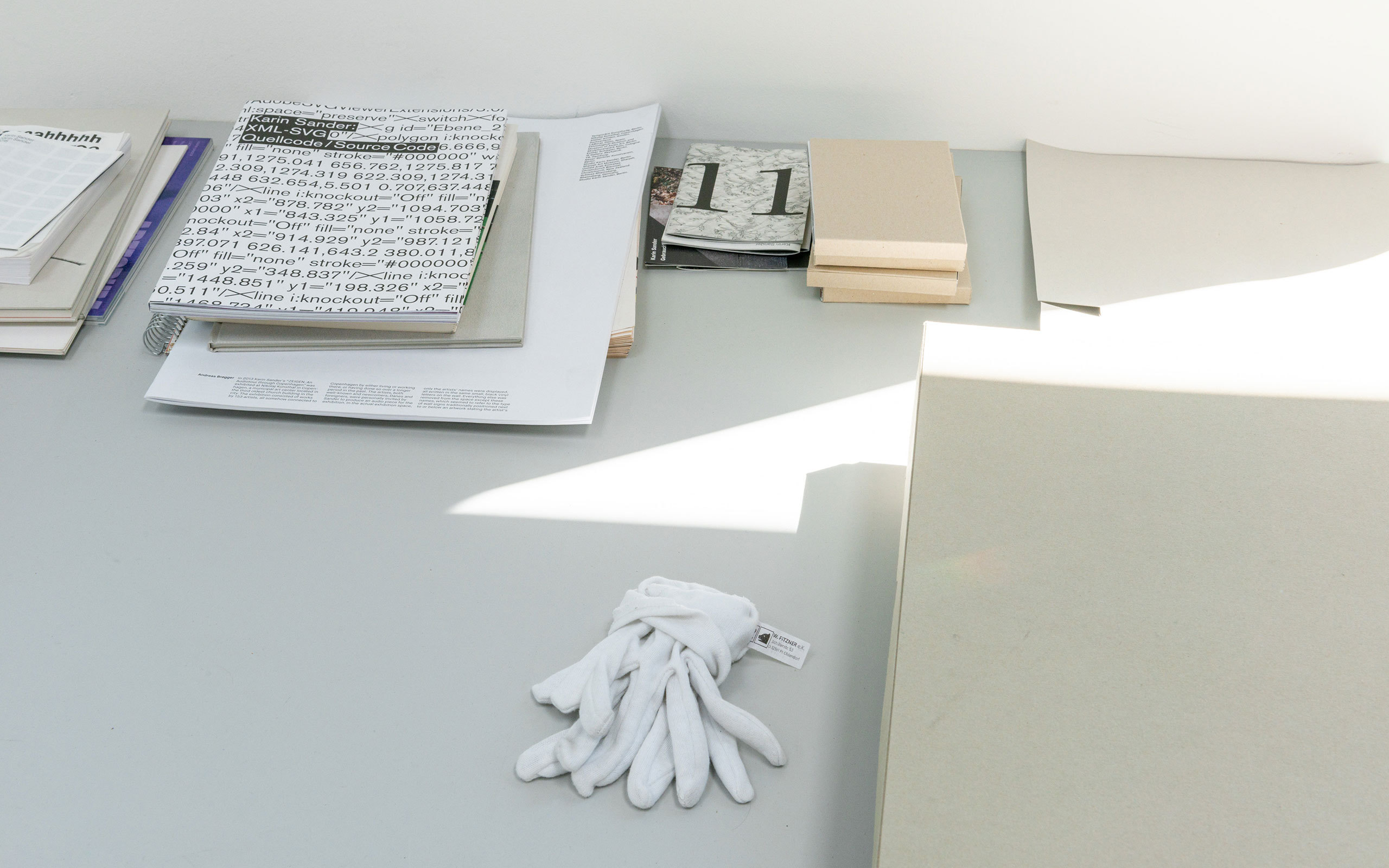

Karin Sander is known for her pointedly conceptual works, like drawings with applied office materials, polished chicken’s eggs (Hühnereier), polished wall pieces, Patina Paintings, Mailed Paintings, figurative sculptures of living persons, Kitchen Pieces and others. She alters the state of things that are already there, be they objects or rooms. In small interventions into the situation, she exposes its material conditions to establish a minimal difference between everyday life and art.

Judging from objects such as the Polished Chicken Egg from 1994 or your series Kitchen Pieces materiality and attributes of these everyday objects seem to interest you. It appears as if you’re playing with the superficial, questioning “everyday” things as perhaps even “fake”. What is your idea behind alienating the “everyday”?

Each of the works you mentioned has a different background and my use of them is surely not about alienation, play, or irritation. The Polished Egg was part of the exhibition Embodied Logos and is self-explanatory; it’s similar with the Kitchen Pieces, at least when one recalls images from art history. They are simply being shown as they are; although they may look artificial, since they are hanging like pictures on the wall.

In Kitchen Pieces, actual “genuine” fruit and vegetables are used, they are not preserved, so they will decay. How are collectors to treat them?

The Kitchen Pieces will wilt and dry out, and are simply replaced when the collector deems it necessary; a restorer is not required.

The issue of material and its properties continues in your glass sculptures. Here you are working with techniques of flow and dripping which involve the reaction of the glass to heat and cold. To what degree does control or loss of control arise as a result of this process in regard to the end product?

To have control over the material is important for safety reasons for example. I work with the viscosity of glass and know how the end product is going to look; I can influence that at any moment.

You are an artist who has exhaustively investigated 3D technology and you’ve continued to do so since 1998, your efforts have culminated in the development of written programs that enable the participation of exhibition visitors.

I first conceptualize a work and I then seek an appropriate technology in which to realize it. In this instance, this was in 1997, I had envisioned a kind of three-dimensional photography. I hadn’t realized that up until then nobody had achieved this and just how complex it would be. A specific program had to be written for this work. I had used the prototype 3D body scanner built for dimensioning at Utrecht University and programmed to produce a portrait of the curator of the Small Scale Sculpture Triennale, Werner Meyer. The process was developed with the cooperation of technicians who emphasized the importance of generating an as dense as possible network of 3D information from which to generate a closed body. With the help of an extruder and a 3D printer it was possible to print the portrait figure as intended in terms of resolution and data density on a scale of 1:10.

Does digital development limit or open up new possibilities?

In 2007, ten years after the 3D experimentation I’ve just described, I was appointed to the ETH Zurich where I could continue to work with regard to interior and exterior spaces and negative volumes using the scanner, built for my chair and develop a well-equipped laboratory in my department for 3D Photography. So far, I see no limits.

Later there were a number of exhibitions in which visitors could scan and print themselves in 3D in the form of small colored figures resembling casts, which became part of the exhibition and in some cases even part of the museum collection. How would you describe the artistic concept behind this?

Since visitors decide for themselves how they wish to be seen and in what position as figures, I would speak of their participation as a form of self-portrait.

Does this work have a performative character that is performed by the visitors?

I would rather say that they participate in the process of the work, and that they become actors in the art business.

This year you were part of the group exhibition “The Future is Female” at SODA Gallery in The Hague. How do you see the situation of women in art today?

It depends completely on the conception of the individual exhibition. That women artists are often not sufficiently represented depends on the fact that some curators are careless or just not well informed.

Interview: Alexandra-Maria Toth, Julia Rosenbaum

Photos: Michael Danner