Kasper Sonne is one of the names that have all of a sudden swept the art world, launched by the power of the world wide web. The Danish artist who lives and works in Brooklyn, New York, became well-known for igniting painted canvases or dousing them with corrosive chemicals. We sat down with the rising star to talk about his sudden fame, his roots, his reluctance to “feed the market” as he puts it, and about the destructive, polarizing powers that have come to characterize his work.

Kasper, you had a lot of solo shows over the last few years and popped up on the radar of many collectors especially on the Internet. How did that start?

In fact my first solo show was in 2002. That was ten years before I began to have the kind of success that came later. So for a long time, I was making work and doing shows but was unable to sell anything. I had to support myself through other means than my art. The weird thing was that at first I wasn’t even aware of the attention I was getting. The first series that blew up on the market was “Borderline”. I had done it in 2009 and back then nobody cared. It wasn’t until someone on the Internet labeled my work as Process Based Abstraction that it became noticed.

It must have been weird to be all of a sudden cast into the spotlight like that. How did you react to your new situation?

When I suddenly got all this attention that I had been diligently working towards for a long period of time it was very difficult for me to say no. But there was a point where I had simply overcommitted myself. It felt a bit like having a factory job. I had a schedule in front of me saying how many pieces each gallery wanted because so many collectors were asking for them. Every time I came to the studio I would have to look at this list so I knew what I would have to make. The reason I’m an artist is that I like to make things. I have that need in me. But that’s not how I enjoy working! At one point I just couldn’t make myself do shows with five galleries anymore. It felt like having five girlfriends fighting over my attention.

You then decided to stop working with all the galleries you were doing shows with. What made you take that drastic step?

First and foremost it was a personal decision based on the fact that I didn’t feel like we wanted the same things. The relationship between an artist and a gallery is a very personal one, much like a marriage. There is a lot of trust involved. Before you get married there is a period in which you are dating and if that works out you might move in together and maybe later you get married and have children. So all I had been saying to the galleries that wanted to do shows with me was, “Okay, let’s do a project together and see how it works out.”

And then you left because you weren’t ready to settle down?

I have a really clear goal in mind: I want to have a long career. I’m not interested in just selling a lot of work to quickly make money. That is why good management from the gallery’s side is so important to me. What I’m looking for is a long-term relationship with commitment, mutual understanding and respect. And, of course, it is also about personality. I’m Scandinavian so I’m very organized and punctual. All these things are ingrained in the society I grew up in. So I need to work with somebody who also functions that way. If people don’t respond to my e-mails in due time I feel disrespected.

But don’t you struggle to reach your audience now that you are not doing shows with galleries anymore?

I’m fortunate enough to have a pretty strong collector base that buys directly from me and I work with a few trusted advisers. So my work sells very well. That’s how I maintain my practice at the moment. My only concern is that at some point I will need to make an exhibition. I’m not only making art so it can get shipped directly to a collector. For me my work is a way of communicating with the surrounding world and being a part of that world. If I don't want to do this exhibition with any of the galleries that offer me shows I’ll have to figure out some other way.

You’re saying your goal is not to sell as much art as you possibly can. For many people that might seem like an odd statement.

During recent years the demand for my work was over the top. I had to pull back and slow it down to make sure that my work didn’t just go to all the known investors and flippers. That is why so little of it has been at auction compared to other artists from my generation. I think the reason I understood that is that even though I was put in with this group of emerging artists I’m older than most of them. I’ve had a longer career outside the art market and along the way I figured out what I wanted: a steadily progressing career.

Formerly it would have been one of the responsibilities of a gallery to strategically manage an artist’s career in the way you are describing.

For me what you’re describing, the old idea of galleries nurturing an artist’s career, represents an ideal situation. I didn’t leave my galleries because I don't want to have gallery representation. The galleries I worked with were young and inexperienced. So in a way I was their mentor and had to tell them what to do and what not to do. I would have preferred to be in the reverse situation where the gallery makes sure that they only sell my work to selected collectors and place it carefully in certain institutions. A gallery shouldn’t sell out a show in five minutes to people who contacted them through Artsy just because they can. I would love to be able to leave these decisions to a gallery, so I can simply be in the studio and work.

It seems as if you have a strong wish that the work you create goes into responsible hands. Like if someone is selling their cat they want it to go to a good home. Is that a comparison I can make?

I totally understand your comparison. I take it personally when somebody tells me how lovely my work is and then turns around to sell it at auction for a profit. Of course, I take no offense when somebody liked the work and their taste changed over the years or they had to minimize their collection or they sold it to buy something else. I just happen to love art and take my job very seriously so I don't want to be a stock that is traded for mere profit.

All this sounds like you would advise young artists right now to resist the temptation of the market at least for a little bit.

Definitely. I think there are a few cases where artists’ careers were damaged because of overproduction, bad management and certain so-called dealers and collectors. But I truly understand the temptation. Imagine you come out of art school here in the US with student debt of a hundred thousand dollars and somebody is offering you fifty thousand dollars to buy a hundred paintings. What do you do? You might know it’s a bad deal but it cuts your debt in half and on top of that somebody is telling you you’re amazing.

You live and work in New York but you were born and grew up in Denmark. What did moving across the Atlantic mean for you as an artist?

Ever since I was a teenager I wanted to live in New York. I didn’t have a sense of belonging in Denmark and I thought from how New York was portrayed in popular culture it seemed to be a place where there is room for everybody. You can look and behave any way you want and nobody takes notice. People might even celebrate that you’re different! This idea that I can be whoever I want to be was what attracted me to New York. Denmark on the other hand is a very small country and you can’t stray too far from the path before people start noticing you in a negative way.

So you wouldn’t describe yourself as a Scandinavian artist even though you were born in Denmark and studied there?

No, I wouldn’t for two reasons: First, because I never had this feeling of belonging in Denmark and secondly because I did not actually study art there. Rather, I attended the Danish National School of Design. When I started showing my art in Denmark the fact that I didn’t go to art school was definitely something that the people in the scene noticed. I was made to feel like an outsider who was only claiming to be an artist. That is why I never really identified with the Scandinavian art scene. I’m not even sure if there is anything you could call “Danish art scene” anymore. When I left Denmark twelve years ago you could still have a career through the state grant system and local museums and galleries. But now everyone’s aspiration is to go to international art fairs. The whole scene has become very globalized.

Why did you decide to study design instead of doing art right away?

I come from a very socialist background and I was always told that you have to contribute to society. My sister is a cancer research scientist, my mom was a special needs teacher and is now a therapist and my dad worked to create youth programs for disadvantaged children. So this idea formed in my head that being an artist was an anti-social and selfish decision. But there was no doubt for me that I wanted to do something creative. First I wanted to be a cartoonist because I loved drawing and making up stories. I even had an agreement with my teacher that allowed me to draw on my table because they found out I was actually paying more attention that way. (laughs) In the end my reasoning was that a designer is creative but also serves the greater good by being a problem solver.

Still your need to create art prevailed eventually. Why?

On the one side the selfishness of being an artist really went against my upbringing. But on the other side I felt it was the closest you can come to autonomy in a normative society. I wanted to be an artist so I would be left alone in my own little world. For me art is something like a sanctuary, a place where I can go and be myself. An artist might still be part of society but he is definitely on its fringes. That way you’re allowed to comment on society. It’s almost expected that you question it.

Let’s talk a bit about one of your most well known bodies of work, the Borderline series in which you have worked with fire to manipulate your canvases. How did you happen to set your first painting on fire? Did you have a painting that you wanted to burn or did the idea of setting a painting on fire come first?

The starting point was definitely not a painting that I wanted to get rid of but a purely conceptual idea. One of my main inspirations was the thought of how much we like to put everything into categories and how much the world and life in general is experienced through oppositions. I’ve always been interested in conflict and polarization. As I get older, I realize increasingly that this might have to do with the fact that I felt I wasn't who I wanted to be when I was young. So in terms of this body of work it was the idea to first create what I call the perfect monochrome painting by applying five coats of industrial paint with a roller and then doing the complete opposite: setting it on fire with a blowtorch. What was left after putting the fire out would be the painting.

What oppositions did you capture by creating work like that?

Parts of the pieces would be burnt, but that which remained would still represent the perfect monochrome painting. For me that opened a space between several opposites: the perfect and the imperfect, control and chance, creation and destruction. My interest was to explore what happens if we merge two known opposites together and give them equal space. What happens if you as the viewer have to step in and decide because an object no longer clearly belongs to one side? What if something can be two things at the same time?

I find the way in which the burnt hole in the canvas reveals the framework of the stretcher bars and the wall behind the painting very interesting. It’s almost like a window.

I like that idea. The frame and the wall are things that are normally excluded from a painting so you could almost argue it’s a sculpture. I try to maintain an openness to my work. I don’t want to be didactic and I don't have a specific agenda I want people to believe. That’s why I prefer asking questions to giving answers. Whatever people read into it is the right answer. If you are well versed in art history you can mention Lucio Fontana or Yves Klein’s burned paintings when discussing my work. But I’ve also talked to someone who was reminded of the burning of crosses by the Ku Klux Klan or Satanism. That is interesting to me because it means that somebody is reading something into my work that is based on their own experiences and has nothing to do with me.

You described the process of working on your Borderline series as something like a rebellion against the perfect surface. Is there a certain satisfaction involved in setting these canvases on fire?

I think that is where my work deals very specifically with myself and my internal conflicts. I would argue that most people are comprised of very different personalities. We are all a bit more complex than society allows us to appear. I definitely feel satisfaction in creating a perfect monochrome painting. A part of me is very linear and conformist. But I also hate that part. I hate the rigidity, the control and knowing exactly what is going to happen. So after doing the boring work of painting I reward myself with the fun of destroying the product. If I had full control and knew how my work was going to turn out it wouldn't be interesting to me.

You have not only worked with fire but also with chemicals. Was making the TXC series very different from the Borderline series?

Even though the process was different the concept is the same as with the Borderline series. It was also a way to oppose the perfect monochrome painting and explore the conflict between control and chance, creation and destruction. The direct negation of painting is to pour paint remover on the canvas. So that’s what I did. I experimented with different chemicals some of which I definitely shouldn’t have used. Eventually I settled on pure bleach because it was causing various interesting color changes and it wasn't too toxic.

How do the Borderline and the TXC series connect with your video work, which seems very different at first glance? Or are they completely separate parts of your practice?

I don’t see them as separate because I know they come from the same source. Just like my other work the text-based videos are all about negation and opposition. I show statements that try to convey some sort of truth. But then the next sentence completely negates what the former had said. For me that speaks about how everything is a matter of context and interpretation. What you experience as the truth might not be how I experience it.

Much of your work is very physical, also in the way it is produced. Another part of your work is more cerebral and conceptual. How do you balance these two opposites?

I definitely have a need to make things in a physical manner. That is true for the Borderline and TXC series and especially for a sculpture titled Body Parts for which I kicked and punched clay. But I also have the urge to fit my work in a big conceptual framework. Body Parts is not only negative imprints of the human body but also the opposite of classical sculpture. I also use language a lot in my work. Language is such a powerful tool to get people’s attention and to make them think about things. That also includes the titles of my work. For example I chose Borderline (New Territory) because on the one hand there’s something borderline about the act of setting something on fire. And on the other hand the burnt holes are creating the shapes of fictitious countries, new borders. Like that I incorporate text in my work even though it’s not text-based.

So the physical and conceptual aspects of your work are interdependent. Do you come up with a concept in advance or do you start by experimenting?

I never just stand in front of a blank canvas and simply start doing things. Even when I’m trying something out it’s based on an idea about what might happen. On top of that I throw half the things I make away because the outcome wasn't interesting or the idea behind it wasn't good enough to support the result. I would argue that it’s not too difficult to make a pretty painting. It’s difficult to make an interesting painting. I’m not too fond of art that just looks good. Our world is pretty fucked up and maybe there’s a need for beauty and pretty things. But I just don’t find that interesting. I like art that provokes me and makes me realize things I hadn’t thought of yet. If I don’t understand it and it sets off a thought process, that’s what I enjoy.

You work in all these different media making paintings, sculptures and videos. Do you have a field that you most identify with?

I have fought my whole life to break out of categories. I have a strong need to express all parts of me and not just a specific one because I happen to be a painter or a sculptor. Sometimes I’m surprised when I see artists who reproduce the same kind of work over and over. My theory is that it feels safe for them. For artists there are no certainties, no guarantees. You are not promised anything. If anything you’re promised nothing. Most artists will never ever be able to sustain themselves from their artistic practice. So once they have found something they have some success with they are afraid to break out of that mold.

Does that mean you work in many different directions to avoid the risk of becoming too comfortable and repetitive?

I have this reflex of thinking, “If this is what you want, then I don’t want to give it to you! You expect this from me? I’m definitely not going to do it!” That’s the non-conformist in me. But of course it might also be a little childish. That was the case with the TXC series. It was my most popular body of work but still I decided not to make any more of them. The main reason was that I wasn't excited about making them anymore. I had them figured out. I had mastered the process and knew what I could and couldn't do. I had become too good at controlling the process. Painting, pouring the chemicals, deciding the piece is finished, taking a picture, sending an email to a gallery, receiving an answer that it’s sold – it just became this very tedious process.

I can understand why you wanted to get out of that. But wasn’t it hard to give up such a successful project?

It definitely went against the logic of the market to stop making something everyone wanted. For me it was a way of saying, “Fuck you, I’m not going to feed the market!” Yes, it’s nice to make money, because that means I can maintain my studio and survive as an artist without having to do odd jobs. For me money only means one thing: the freedom to do what I want to do and not what other people want me to do. As long as I have enough money to do what I want to do you can’t make me do anything else.

Your art can be seen as quite dystopian. Destruction, opposition, polarization – there are almost violent themes in there. Can your work be understood as commentary on current events? Is your art political?

I don’t sit down, read the news and then pick topics to comment on with my work. But destruction and dystopia have always been present in my work and the world is constantly at war. So of course you could argue that I’m informed by what’s going on around me. After all I’m a human being with political views. For instance I was devastated by the result of the last election here in the U.S. because I feel it was an attack on everything that I moved to New York for. That might creep into my work somehow but I’m never commenting specifically on certain issues and I don’t see myself as a political artist. I think people who see themselves as political artists would be very upset if I did, because I’m way too commercially successful and I make good looking paintings. You’re not supposed to do that if you’re a political artist.

What about the way some people see your work as a linear extension of the work of major names like Fontana and Klein? Does that connection have a meaning for your work or is it a burden?

I do think about art history. It’s another layer to my work – no more and no less. Fontana’s work was about spatial compositions and the idea of exposing the space behind the surface. Yves Klein made these abstract shapes by scorching wood but he never had an uncontrolled fire. By making something perfect and then doing the opposite to it I reference their work but follow my own path. Like that art history can be a guide for my work but I’m not interested in making art about art. That’s too narrow for me.

Apart from those we mentioned, are there any artists who have inspired you and whom you admire? I like a lot of different art and I like it for many different reasons. If I had to name one artist who I have the utmost admiration for it would be Bruce Nauman. His work keeps being interesting to me because he is exploring what it means to be a person in this world in so many different ways and media. But then I can also stand in front of a Rothko painting for hours. For me this physical experience of art is very important. Among the contemporary artists I have the highest respect for is Wade Guyton. He makes really pretty abstract pieces but in a completely surprising fashion. He has taken the digital printing process to an entirely new level. With him the method is part of the concept.

Do you also collect art yourself?

I have a very limited collection, a small Wade Guyton edition for example that I was very lucky to buy at an art fair back in 2008. It’s one of my most cherished possessions. Somebody mentioned that they sell for high amounts at auction. But even if I sold it them I could never afford another Wade Guyton nowadays. I also have a Ugo Rondinone edition: one of his “Seven Magic Mountains” sculptures that I bought from Art Production Fund. If I had more money I would definitely buy more art. I would also like to trade more with other artists.

You said you never want to do the same thing for too long. So I’m curious to know what you are planning. What’s next for you?

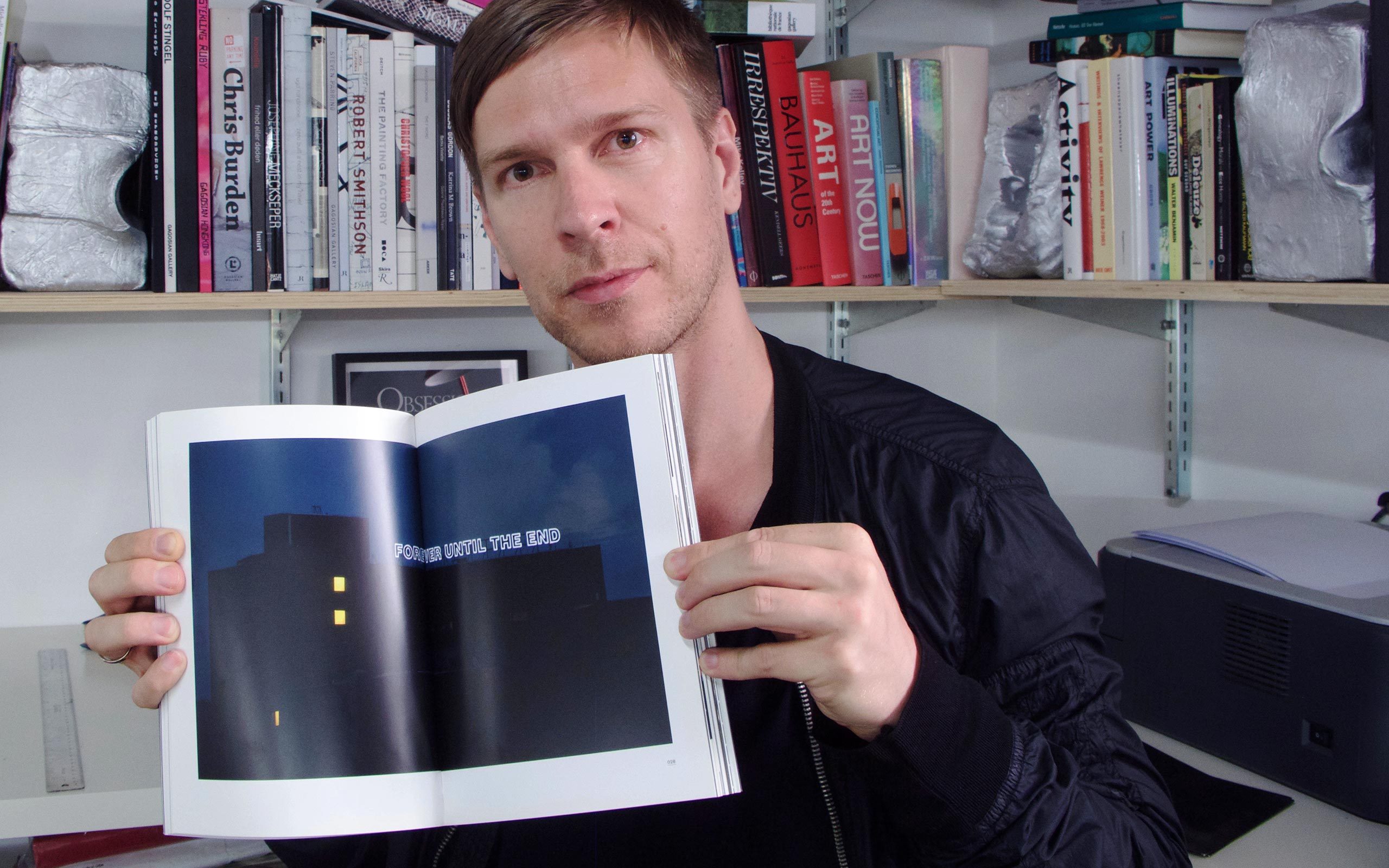

I’m always exploring things. For me my studio really is a place of total freedom. When I come here I shut the door and leave the outside world and its expectations behind. In here I allow myself to experiment a lot. But as I mentioned earlier: Half of it might never amount to anything. More concretely I’m part of a group show that will open in November at a museum in Bern. In 2008 I did a huge sign on a building that said “Forever until the end“. They will reproduce that and put it on top of the museum. That’s the only thing that I’ve said yes to so far because I’m really enjoying this moment of time where I can just be in the studio making work.

So what kind of pieces are you working on at the moment?

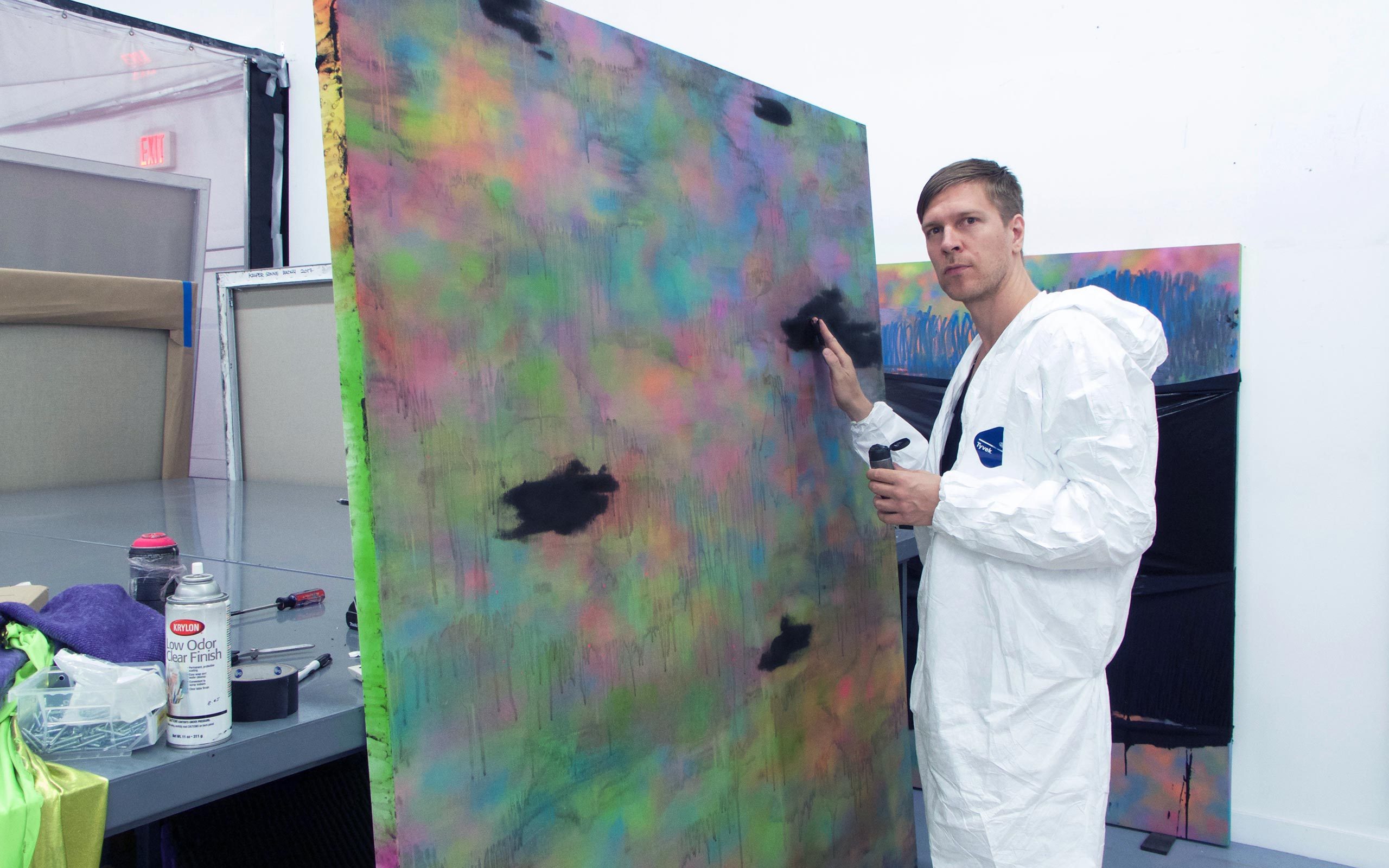

I’m currently working on paintings with volcanic ash, and recently I started exploring how I could make them with color. I've also been working on another painting series for over a year and I’m only now starting to be satisfied with the results. I call this series “Holistic Paintings” as I’m incorporating things from my time studying fashion design, like fabrics, as well as elements from recent works, like the burns, and materials from other types of works I’m experimenting with in the studio. So they’re basically comprised of things from my past, present and future.

Interview: Gabriel Roland

Photos: Courtesy of Kasper Sonne

Links: