Katrin Hornek’s work testifies to her astonishment when looking at our world in which humans, in the age of the Anthropocene, have become an influencing geological factor. She deals with the interfaces and interdependencies between nature and culture and shows how human intervention affects the present and future of our planet. In her research-based practice, Hornek follows up stories in various archives. Through them, she builds narratives that open up a new perspective on our world, using various installations.

How did you get into art?

I was actually always drawn to natural sciences; I was debating whether I should study biology or art. However, I found the language in science too cryptic, it often forms a barrier, a distance…

So you weren’t always drawing – like so many other artists?

I did draw, but I’m not particularly good at it (laughs). Funnily enough, I took art as compulsory elective subject at grammar school; and I was fascinated by working on oil paintings. So the choice to study art was ultimately a gut decision – and luckily Monica Bonvicini accepted me at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. From then on, I never picked up a paintbrush again in my life! Instead, I began to take an interest in research-based subjects. Today, I combine art and science through my work.

What kind of media did you use at first? Did you ever paint or sculpt?

I only painted prior to the entrance exam, after that I switched to working more in the way of a documentary, mainly through video. My final project at the Academy was about genetically manipulated fruit flies that had been grown to have armpit hair – very bizarre. My then roommate was doing a PhD at the Institute of Molecular Biotechnology and had told me about the idea of visually marking fruit flies using armpit hair (laughs).

How did you turn such an observation into art?

I just thought it was so absurd! That was also the time when I was very influenced by gender studies, and armpit hair was a big topic at the time anyway (laughs). And I’ve always had a passion for telling stories. In my art, I want to find formats to tell these stories which I research, stories that have triggered me or that I find weird. That’s the challenge: how do I translate a certain topic artistically?

What media do you use to this end; do you combine video and photography?

Not anymore. It really depends on what my subject is. I sift through the material and try to figure out what the best medium would be in each case.

And the art ultimately comes into being through the viewers themselves?

Yes, absolutely! I build a space in which you can move. It is also space in the sense of research, sometimes I also offer coordinates. Whether it is art is probably also defined by the framework in which the work is being shown.

Would you subsume your art under conceptual art?

Mine is a research-based practice with a very strong reference to location. I love starting from certain materials and localities, because they give me the anchoring and the foundation from which I can explore further – you can see that quite well in the testing grounds project, for example.

In this project for the Secession, you combine geology, archaeology, geoinformatics and art. How did that come about?

The decisive factor was a WWTF call (Vienna Science and Technology Fund). As part of the interdisciplinary project “The Anthropocene Surge”, the history of Vienna was being researched using the methods of sedimentology, geoinformatics, archaeology and art, on the basis of human deposits underground. The exhibition at the Secession is my conclusion of this project.

Can you explain the project?

It’s about the Anthropocene – the new age in which humans have become one of the most important influencing factors on biological, geological and atmospheric processes on Earth. During the excavations for the new Wien Museum, certain particles were found in those sediments: they were global fallouts from above-ground nuclear bombs dating from the period after the Second World War. And according to the Anthropocene Working Group, this was to be the marker to determine the beginning of this new age. Because the atomic bomb tests have supplied the whole world with radioactive dust.

How do you translate this idea into art?

The whole project is an eight-channel installation, and there is also a performance. The main room of the Secession gives the feeling of being inside a cathedral: the ceiling shows a photo of the Baker Craters, which is reflected in eleven-meter-long pools on the floor, filled with black water. People will wonder whether this is a cemetery, a devastation zone, a dubious waiting room or a home for mutants…

Why are you also including a performance?

I found my research on plutonium – based on the sediments from the excavation at the Wien Museum – to be so brutal that I was afraid I wouldn’t be able to form the respective artistic language. That’s why I wanted to work with someone like Karin Pauer, who translates themes through her physicality, her body. In any case, I found the topic so disturbing that I needed friends by my side. In addition to Karin, I engaged with Zosia Hołubowska, who was responsible for the sound, and Sabine Holzer, with whom I worked on the written pieces.

You seem to combine a lot of content…

That’s generally my artistic strategy! I often pick an element or a fragment of history that interests me, and then I follow it through various archives. Doing my research, I come across different impressions, and I want to make them tangible through my work. I have always been interested in the relationship between so-called “culture” and “nature”. The Anthopocene opens up this space in which man suddenly has geological power to greatly change his surroundings.

You speak with so much enthusiasm that I wonder whether, alongside the scientific research, some emotions might have come up?

Normally I try to keep my emotions out of my work, my position is a distanced one. But this time… For testing grounds, I spoke to many people who had been affected by nuclear testing, and whose voices I include. There’s Karypbek Kuyokov, for example, an activist who was born without arms. He grew up near the Semipalatinsk Test Site, where the Soviet Union carried out tests for nuclear weapons until 1989. People were not informed at all… To this day, the test site is not fenced off and the local orphanage is overcrowded with children with severe birth defects.

Do you think you can give them a voice through your work?

It was catastrophic: not only the atomic bombs themselves, but also the tests on Bikini Atoll. The people there were relocated to another island, but during the tests the wind carried the radioactive fallout over there… What does that tell us in today’s world, regarding the current arms build-up? I think I’m just amazed at myself, at how little I knew about these things. I want to share my bewilderment.

What was particularly challenging about this work?

Usually, I like to use humor to take people along with me on the ride. But that just doesn’t work with the subject of plutonium: I can’t be cynical, I can’t be funny… Because it’s just not funny anymore! You touch this excavation on Karlsplatz, the location of the Wien Museum, and you know you’re touching a particle of the Bikini Atoll. And the Bikini Atoll is in our bodies too, and let’s talk about what that means! It’s hard for me to say: “Oh, I’ll just deal with it artistically”.

What kind of reactions do you expect?

My intention is not to tell people: “Sit down and cry!” I don’t want to educate or lecture anyone. But whoever wants to go along should do so. I try to find aesthetic forms of translation to open up spaces of association, to perhaps make things appear more connected.

Or more tangible…

…more tangible, more localizable. I want to offer a sensual perception, an immersive experience.

Do you sometimes find your work dystopian?

Mostly I want to offer an associative way of thinking about the future; I want to take humankind a bit out of the center of the world. Just because our world is ending, it doesn’t mean that the world itself is ending.

Another project of yours was Stones like Us. It’s about body stones that you exhibited in a cave. How did you come up with this idea?

When I heard about the idea of the Anthropocene, it really got me thinking: What does it mean when humans are geological forces? In this context, I found it exciting that we ourselves develop small planets in our bodies – body stones – that mediate between the stone-like and the human. Our bones are also related to corals! In the course of my research, I found out that weddellite is the second most common body stone produced in Austria.

What is a weddellite?

It can be a component of urinary stones, but it was first found outside the body on a research trip to the South Pole. I think it opens up such big spaces when the cold floor of the Wedel Sea in Antarctica and our bladders can create the same environment to bring these forms into the world!

So you’re drawing our attention to the wonders of the world?

Or rather bewilderments about the world!

Therefore nature and culture are not separate entities for you?

No, not at all. I love the point at which the disciplines clash. For Stones like Us, I worked with Sabine Holzer, and we could show the Tessadri body stone collection for the first time in public, in the Tischofer cave in Tyrol. We put up instructions such as “Touch the cave wall” or “Immerse yourself in this mineral thinking”… It was about how body caves and stone caves relate to each other. People stayed for hours and came back the next day, which was very touching. It created a kind of community, and I thought, that’s exactly what I want.

To really touch people?

Yes, art is often such a gritty business, where you will find yourself in rapports of distance and evaluation. But I get my energy back with these kinds of works; through these moments where I get the feeling that I am sharing something, or that we are embracing something together.

Katrin Hornek, Stone Like Us, 2018, Katrin Hornek in collaboration with Sabine Holzer, Tischofer Höhle in the Kaiser Mountains as part of Kunst im öffentlichen Raum Tirol, Performative installation, Photo: Katrin Hornek, © Bildrecht, Vienna 2024

Katrin Hornek, Stone Like Us, 2018, Katrin Hornek in collaboration with Sabine Holzer, Tischofer Höhle in the Kaiser Mountains as part of Kunst im öffentlichen Raum Tirol, Body stones from the Tessadri Collection, Innsbruck, Photo: Katrin Hornek, © Bildrecht, Vienna 2024

Do viewers need a certain amount of prior knowledge?

People who know a lot, for example physicists, might not like some projects because they will feel they are too emotional. That’s a balancing act, because on the other hand I often hear: “I don’t understand that”, or “Do I have to understand that?” That’s the big complication, of course.

How do you deal with it?

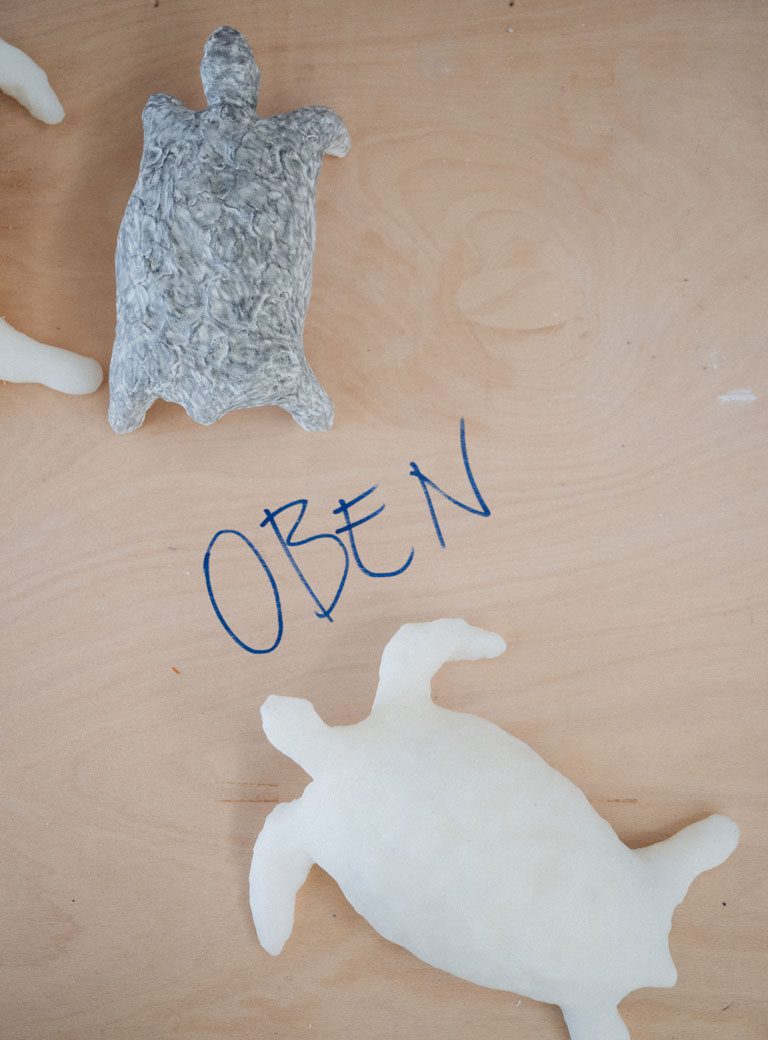

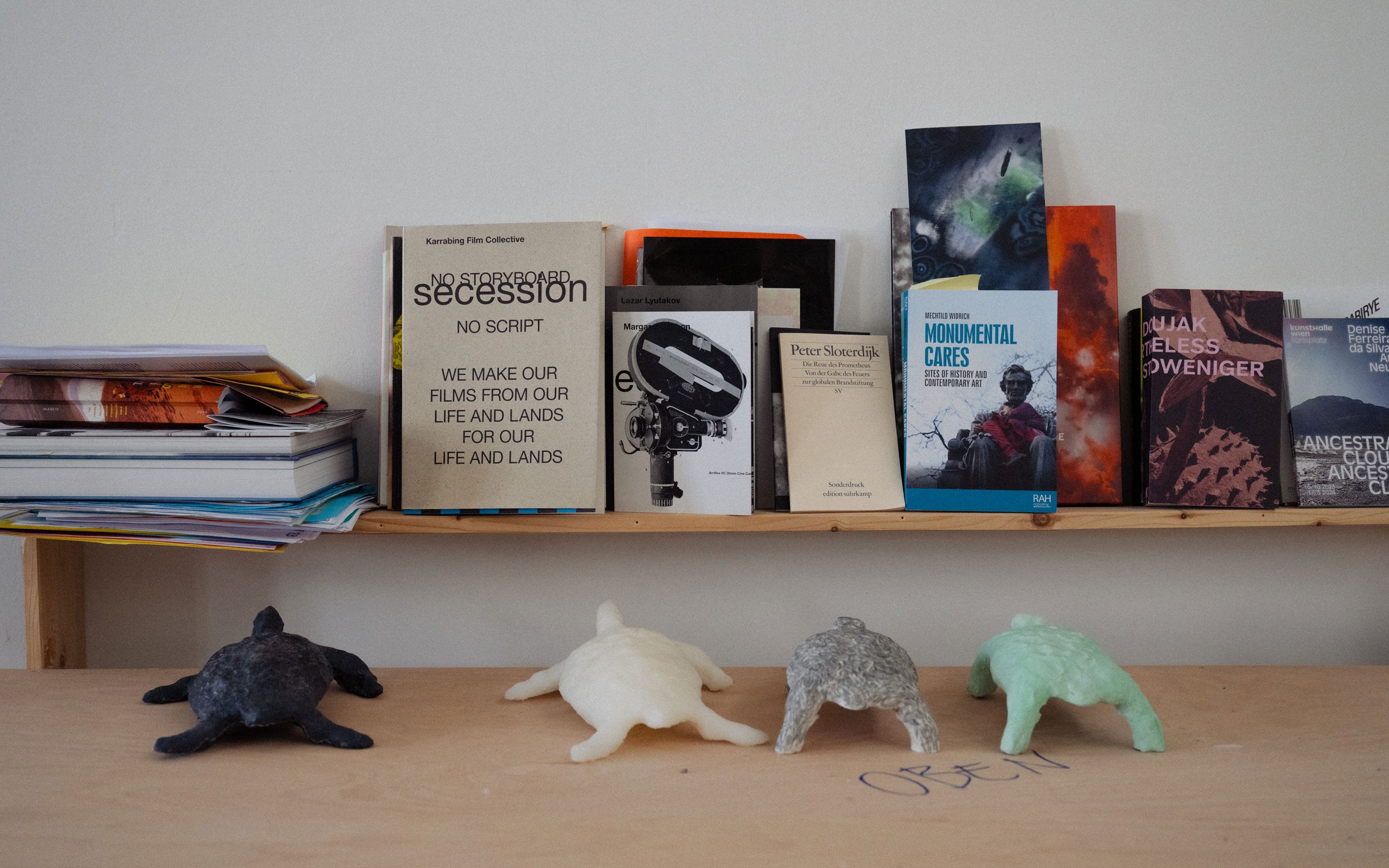

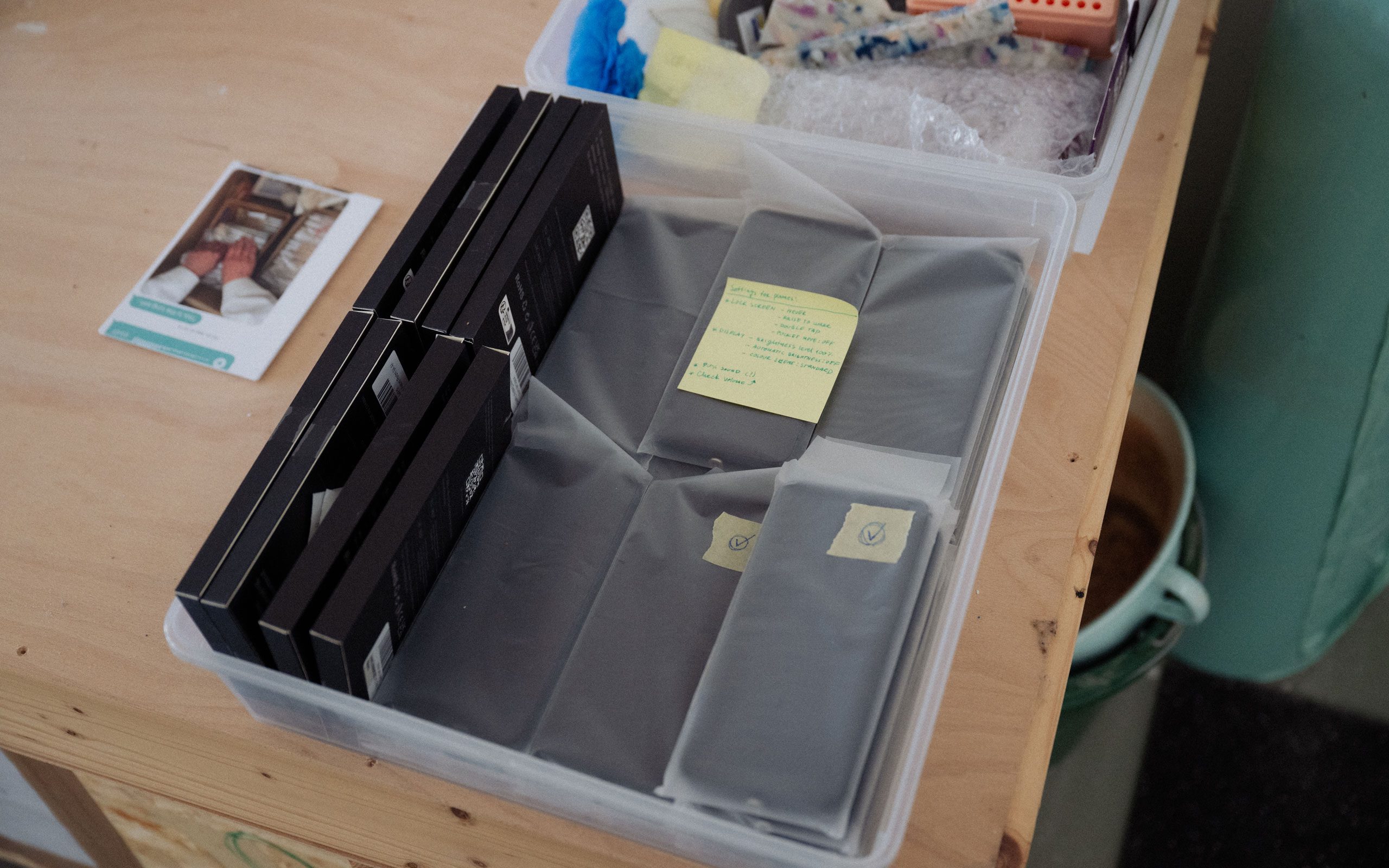

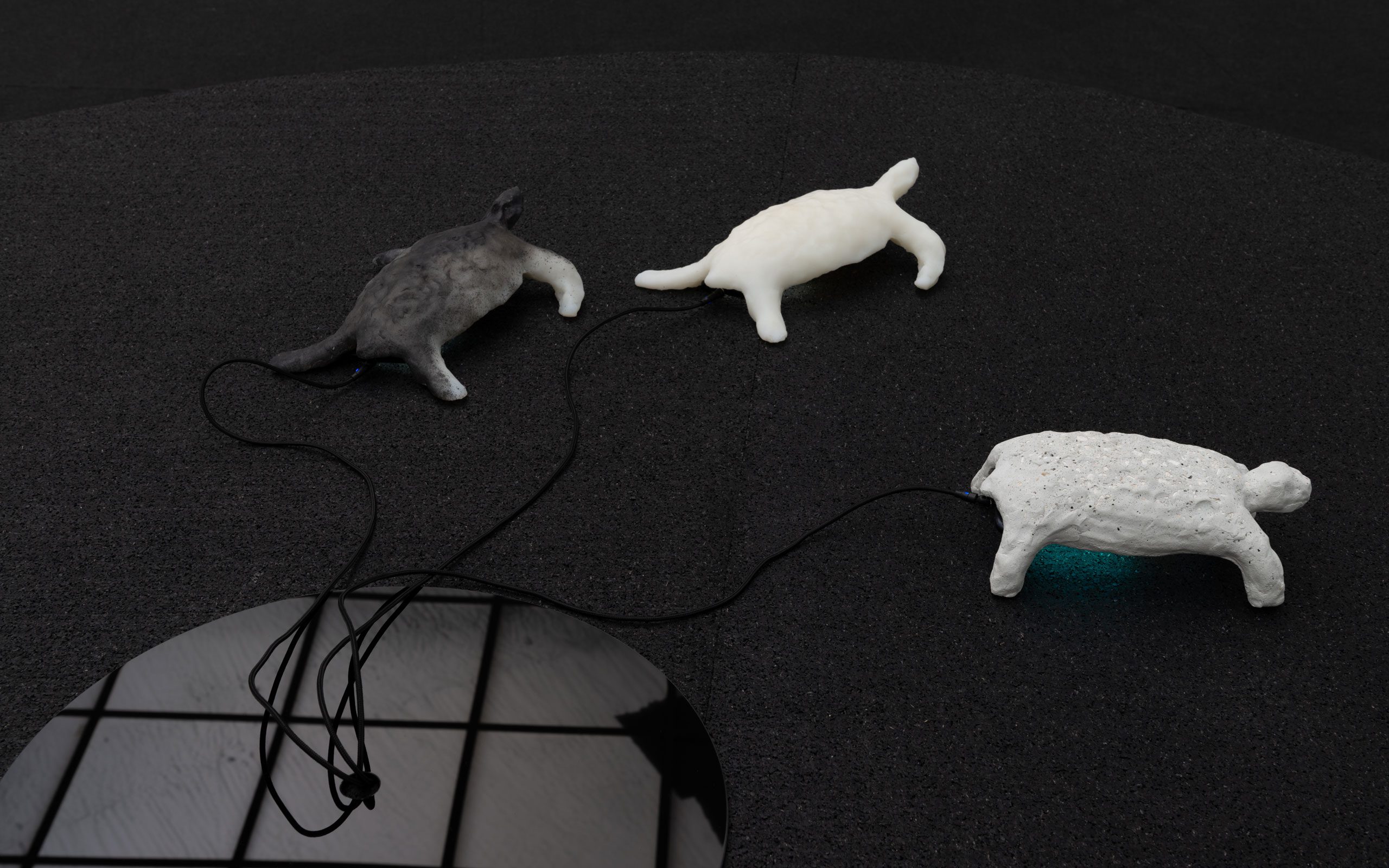

For instance, for testing grounds at the Secession, I used an overwhelming number of media. In addition to the installation, there are turtle-shaped handhelds from which you can listen to texts and accounts of people affected by the testing sites. If you listened to all the material, it would take you three hours. However, you should be open-minded enough to tolerate the fact that you won’t understand everything right away. But if you are happy to engage with the installation, you will certainly take something away with you. Even if you just watch the performance or only take in the sound and the ceiling image: fair enough.

Do you have any new projects in the pipeline?

In 2025, I will continue working with Karin Pauer on the Secession project at Belvedere 21, as we have received follow-up funding from the WWTF. In September 2024, I have an exhibition in LA as part of the GARAGE EXCHANGE VIENNA – LOS ANGELES. And within the scope of Salzkammergut Capital of Culture 2024, I’m showing my project Plant Plant. It’s a film that looks at the history of fertilizer production and its planetary interdependencies, based on findings in a former ammonia factory near Merano in Italy.

What’s it like to live and work in Vienna?

It’s going really well, I think. I got a studio through the BMKÖS (Austrian Ministry of Culture), which supports me; I was able to do a lot of residencies. If I look at friends living in different contexts, you really do get a lot of support in Vienna.

Katrin Hornek, testing grounds; in collaboration with Karin Pauer, Sabina Holzer and Zosia Hołubowska, exhibition view, Secession 2024, Photo: © Sophie Pölzl

Katrin Hornek, testing grounds; in collaboration with Karin Pauer, Sabina Holzer and Zosia Hołubowska, exhibition view, Secession 2024, Photo: © Sophie Pölzl

Katrin Hornek, testing grounds; in collaboration with Karin Pauer, Sabina Holzer and Zosia Hołubowska, exhibition view, Secession 2024, Photo: © Sophie Pölzl

Katrin Hornek, testing grounds; in collaboration with Karin Pauer, Sabina Holzer and Zosia Hołubowska, exhibition view, Secession 2024, Photo: © Sophie Pölzl

Interview: Alexandra Markl

Photos: Christoph Liebentritt